Beyond Nails in the Grocery Store

Son of a pioneer of Colorado’s media world, Hillel Goldberg was expected to continue his family’s newspaper. But a mussar scholar, writer, and seforim author, too?

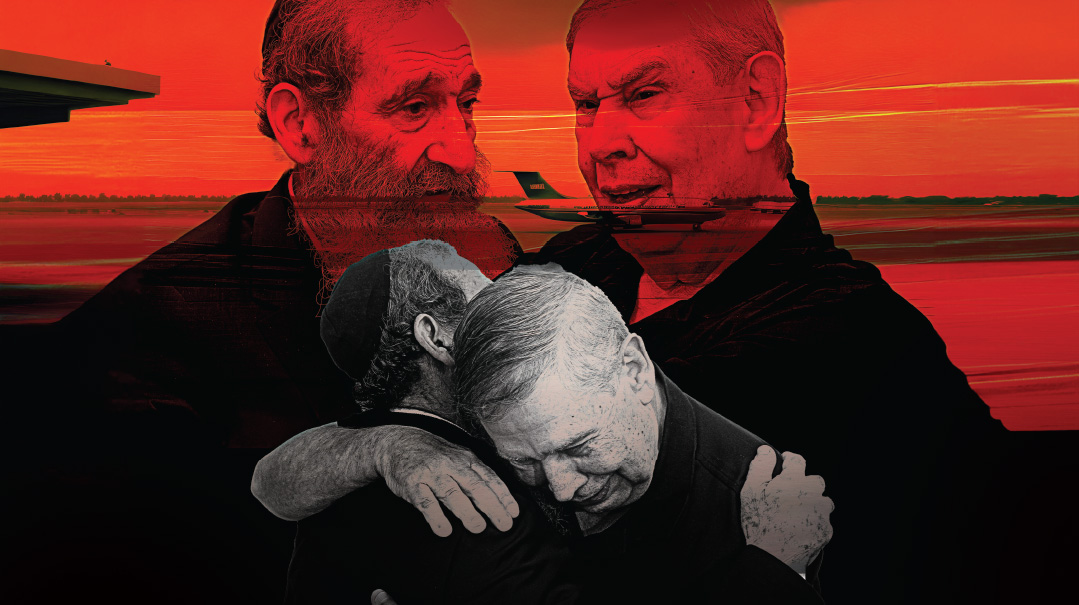

Photos: Avital Rotbart

W hile planning a recent West Coast trip I had contacted Rabbi Hillel Goldberg to ask about interesting people to interview in Los Angeles. I knew Reb Hillel to be well-traveled and a resident of Denver Colorado which to a New Yorker seems like just around the corner from L.A. I wasn’t quite prepared for his response: “I don’t know what topics you’re looking to cover but there’s a guy named Josh who’s the car-service driver I used the last time I was in L.A. and I got a very fine dose of yiras Shamayim listening to him. The number I have for him is…”

It was vintage Goldberg. An intimate of great rabbinic personalities he’s an acclaimed author and award-winning journalist respected in yeshivah and academic circles alike. Yet he takes inspiration where he finds it even in the back seat of a cab — and the vignettes of Jews famous and unknown that fill the pages of his most recent book The Unexpected Road: Storied Jewish Lives Around the World attest to that as well.

Now I’ve come to the Mile High City for an elevating conversation of my own with Reb Hillel and entering his office at the Intermountain Jewish News where he’s the executive editor and writes the longest-running column in Jewish journalism the first thing I glimpse on his desk is a volume entitled Mind Over Man. It’s a newly published collection of vaadim given by Rav Yechiel Perr a rosh yeshivah and leading contemporary exponent of mussar thought.

The warm inscription inside the book reflects Rabbi Perr’s appreciation for Reb Hillel as a longtime student of mussar and the Eastern European–born movement that championed it. His groundbreaking books The Fire Within and Illuminating the Generations helped make the personalities and concepts of the mussar movement accessible to the Jewish reading public. A writer friend recently shared with me that when The Fire Within first appeared he read it and then reread it numerous times in what was a life-changing experience for him.

Keeping It in the Family

That Hillel Goldberg succeeded in forging a link to the storied mussar masters of prewar Europe is all the more striking given his own upbringing in a radically different time and place: 1950s and 1960s Denver. His father Max was the eighth of nine children born to poor immigrants on the city’s West Side. When their father passed away during the worldwide flu epidemic of 1918 it was left to seven-year-old Max and his five older brothers to support the family by becoming newsboys for the Denver Post.

From selling papers on Denver’s street corners Max Goldberg would go on to become one of the major figures on Colorado’s mid-20th century media and political scenes. A newspaper reporter by age 19 and later a radio sports show host for 25 years he also wrote a popular column in the Post that mixed business politics and humor.

Reb Hillel says his dad was someone who “was always doing more than one thing at a time,” a man of action who in the 1940s raised more money in Denver for war bonds than had been raised in all of Chicago. And so, alongside his media endeavors, he opened a public relations firm that handled some of the leading names in state and local politics. That, in turn, enabled him to pioneer in bringing network television to Colorado, securing the FCC license and putting together the business group that bought Channel Nine to Denver.

The capstone of his long media career was serving as host of On the Spot, a highly rated TV show of a genre, Reb Hillel observes, that no longer exists — “a one-on-one interview show on a highly literate level. He was able to get the great personalities of the age to come on his show without fee — people like Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy, Arthur Goldberg, Nelson Rockefeller, George Wallace, Jimmy Hoffa, and the list goes on.”

Max belonged to a “traditional,” albeit mixed-seating, synagogue, and maintained a close relationship with its rabbi, Charles (Eliezer Hillel) Kauvar. Although he was ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary, which is today the Conservative movement’s flagship school, Rabbi Kauvar was in the last graduating class, in 1902, when it was still an Orthodox institution. Rabbi Goldberg says the rabbi “did a lot of mitzvos under the radar, such as helping support a number of impoverished old-time European rabbanim on Denver’s West Side, even raising the money to publish their seforim.”

Max’s long career in media gained a Jewish angle when, in 1943, he and a partner paid one dollar to take over the Denver Jewish community paper, the Intermountain Jewish News (IJN), which had been bleeding money ever since its founding three decades earlier by the local Federation. But in October 1972, just days after his 61st birthday, Max Goldberg died, and the reins of the publication passed to his wife Miriam.

Lacking even a college education, she took the helm of the IJN and, says her son, “surprised the universe” by making it larger and more successful than it had ever been, even if it meant working 12-hour days until she was eighty-eight and a half. When Miriam Goldberg passed away this past Asarah b’Teves at the age of a hundred, she left behind a vibrant, highly regarded newspaper, which has garnered more awards in editorial, reportorial, and design categories from the American Jewish Press Association than any other Jewish publication. Hillel Goldberg himself has won the Simon Rockower Award for Excellence in Jewish Journalism numerous times for his commentary, news reportage, and feature writing, as have other writers on staff.

Despite his family’s lack of Orthodox affiliation, Hillel’s embrace of full Jewish observance came early in life, with much of the credit due to one deeply inspiring mentor: Rabbi Samuel (Zalman) Adelman. Coming to Denver in 1957 from a pulpit in Virginia, Rabbi Adelman spent a mere nine years in the city before his tragic death in 1966 at the age of fifty. Yet, says, Rabbi Goldberg, “it’s fair to say that of all the rabbis who have been in Denver since, he produced more fruits than anyone. I’m one of those, and there are many more, including Denverites who are heads of institutions and talmidei chachamim, as well as many who no longer live here.”

Rabbi Adelman had a tremendous ahavas haTorah coupled with an amazing capacity to communicate, particularly with young people, says Reb Hillel. “He was an original, a trailblazer. He was the youngest man on the RCA’s first rabbinic delegation to the Soviet Union in 1956. He published several books of poetry. He worked on civil rights, fair housing, rights of the handicapped. But mostly what he did was teach Torah, extremely effectively, and without notes. He was a riveting speaker, talking on Shabbos morning in shul for 45 minutes while not a soul stirred. I’ve heard many wonderful speakers, but rarely have I heard anyone who matched him.”

Stadium Subterfuge

Although his religious life had taken a right turn, Hillel continued the family tradition of professional journalism. He began writing periodically for IJN in 1966 and became a regular columnist in 1972. Thirteen years later he joined the paper’s full-time staff, and is now the paper’s editor and publisher.

In this role, Reb Hillel is probably unique in American Jewish journalism: Not only staunchly Orthodox but a talmid chacham too, he heads a community publication that is read by — and thus must be able to relate to — people across the Jewish spectrum. Reflecting on the inherent tensions of the endeavor, he says his goal is “to publish something of integrity, remaining faithful to Torah, while retaining a broad, general Jewish readership. It’s not an easy balance, and every single week, something comes up that has to get taken out or reformulated.”

The editorial staff, all decades-long veterans of IJN, reflects its unusual diversity: Assistant editor Chris Leppek, as a non-Jew, offers a different perspective that, says Reb Hillel, “often saves us from inside-the-bubble errors. People, including in the Orthodox community, often request that Chris cover a given story.” Senior writer Andrea Jacobs, he says, “has grown a lot in her Judaism during her some 25 years with the paper and has written many fine portraits of people in and out of the Orthodox Jewish community.” And associate editor Larry Hankin’s personal journey has taken him from a Reform to a Conservative to an Orthodox synagogue.

“We’re like a family,” Rabbi Goldberg observes, “working collaboratively, with the belief that real professionals should be able to cover anything well, with both the appropriate objectivity and empathy.” Actual family members are part of the mix, too, with daughters Tehilla and Shana serving respectively as a weekly columnist and assistant publisher.

The newspaper proudly perpetuates Max Goldberg’s insistence on using its pages to accord legitimacy and dignity to Denver’s Torah institutions. When Yeshiva Toras Chaim first came to town in 1967, Rabbi Goldberg recalls, “it was looked upon as the oddest thing. For a yeshivah to come to Colorado back then was so not understood. Yet, when the roshei yeshivah walked into this office, and although my father didn’t really understand what a yeshivah was, he said to them, ‘You have good intentions and you want to do something good? We’ll be behind you,’ and that’s how it’s been ever since — and so, too, for all the other mosdos that have been built here.”

In what is one of the longest continuous stints in American journalism, Reb Hillel has been writing for the IJN for 51 years, but until 1985, his columns were usually written far from Denver. In 1969, he married Elaine Silberstein and for the first three years of their marriage, they made their home in Boston, Massachusetts as Hillel pursued graduate studies at nearby Brandeis University. Eventually, he received a PhD, submitting a study of Rav Yisrael Salanter’s life and thought as his doctoral thesis, later published in book form.

During those years, the couple formed what was to become a lifelong connection with the legendary Bostoner Rebbe, although Reb Hillel likes to says it was actually Rav Yosef Ber Soloveitchik who made him a Bostoner chassid. As a newcomer in town, he’d been jumping around between shuls, but after attending Rav Soloveitchik’s famous Motzaei Shabbos shiurim, one of which elaborated on the importance of a makom kavua for davening, he chose the Bostoner shtiebel.

The Rebbe, says Reb Hillel, had an unusual capacity to instinctively understand and communicate with all types of people, frum, not frum, wealthy, poor, spoke English, didn’t speak English — it didn’t make any difference.

“The Rebbe was completely wrapped up in his davening,” Reb Hillel remembers, “his eyes closed the entire time.” But once, some tumult had occurred in shul, yet the moment davening was over, the Rebbe knew exactly what had happened. This wasn’t some mofeis, that’s just who the Rebbe was — completely detached from the world, yet completely attached to the world.”

From the northeast, it was off to the Middle East, more specifically to a new Jerusalem neighborhood called Sanhedria HaMurchevet, where the Goldbergs spent the next 11 years.

Reb Hillel leans forward, smiling, as if he’s about to share a secret. “You know that big hill across from Sanhedria HaMurchevet called Ramat Shlomo? Well, a guy named George Stanislawski and I deserve an apartment in Ramat Shlomo. George is a lovely guy, originally from Atlanta, and one day, George and I were crossing the street in Sanhedria HaMurchevet going in opposite directions, when he looked at me and I looked at him and we both said, ‘They want to build a stadium up there — we can’t let that happen!’

“Mayor Teddy Kollek was determined to erect a soccer stadium in what was then called Shuafat, which would have wreaked havoc on the nearby frum areas, and the campaign to stop it began at that moment.”

HilleI wrote anti-stadium articles in the IJN to raise awareness about the issue, and he and Stanislawski also got local politicians like Agudah city councilman Shmuel Shaulson involved. The two of them “just went around talking about this coming disaster and the initial reaction was, ‘You’ll never get anywhere with this.’ But eventually, it became a cause célèbre and grew way out of our hands, which is exactly what needed to happen for it to succeed.”

Put to the Test

Hillel Goldberg spent his years in Eretz Yisrael learning in the Novardok yeshivah, eventually becoming Rabbi Goldberg. He proudly points out a framed ksav semichah adorning his office wall, alongside a photograph of Rav Elyashiv engrossed in learning, an iconic portrait that can be seen in Jewish homes around the world. It was taken by Reb Hillel’s son, Rabbi Mattis Goldberg, who has published two large-format books featuring his photos of gedolei Yisrael and is a popular photographer for chareidi media.

Reb Hillel received his ordination from Rav Ovadiah Yosef, but it was also signed by Rav Nissim David Azran, a Sephardic rav and father-in-law of former Sephardic Chief Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu. He explains that the Rishon L’Tzion was a very busy man and didn’t have time to give multi-hour bechinos, so he would only agree to give a bechinah to someone who’d already been thoroughly tested by someone he trusted. In this case, that was Rav Azran, who gave Reb Hillel an oral, closed-book bechinah lasting seven hours.

“Then,” Reb Hillel recalls, “I was ready to be tested by Rav Ovadiah, and here’s how his bechinah went: He asked me a question and just as I began my answer, ‘kasuv b’siman tzadi tes…’ he cut me off. He asked another question and again I began, ‘kasuv b’siman kuf daled, se’if daled…’ and he cut me off. He did this maybe ten times in a row. But then he asked me another question and didn’t cut me off, and so I had to keep going with my answer as he sat there and listened to me for five minutes responding in great detail. He asked a few more questions and cut me off, and then a few more questions and didn’t cut me off. And in this way, inside of twenty minutes, he was able to test both my bekius and whether I knew the material well. It was brilliant.”

Rabbi Goldberg also taught for eight years in Hebrew University’s Rothberg program for overseas students, where his wide-range menu of courses was dependent on the school’s needs in a given semester, from Talmud to Jewish Ethics to Modern Jewish History. Those courses became the basis for his book, Between Berlin and Slabodka: Jewish Transition Figures from Eastern Europe, a fascinating biographical study of six brilliant Eastern European Jewish scholars who all spent time in Berlin’s academic milieu, some of them later becoming seminal figures in different sectors of American Jewry.

Although the university is considered a bastion of secular thought, Rabbi Goldberg didn’t find it especially inhospitable to him as a frum Jew teaching Judaic topics. “I believe that if you teach Torah honestly, you can meet the Torah standards and the academic standards, so I didn’t have a conflict. And they didn’t have a conflict with me. And I also got to influence a lot of people,” he says.

One of the Goldbergs’ neighbors in their Sanhedria HaMurchevet days was the unforgettable Rabbi Nachman Bulman, who became a treasured mentor to Reb Hillel. His pithy assessment of Rav Bulman is that he was “an unbelievable mind, an unbelievable neshamah and, of course, an unbelievable teacher.” But that raises an obvious question: Why did this Jewish polymath, at home in virtually every Torah school of thought and so overflowing with ideas and passion, leave behind so little in print?

“You know,” Reb Hillel says, “he had 50 books in his head and it was a tremendous tension that he carried with him. He would share with me, ‘When am I going to write?’ Part of it was that he was always so busy trying to sustain the various institutions he was involved with, some of which he had founded. He had a sort of writer’s block, but it was more than that. There was something that held him back. But another reason he couldn’t find the time to write was that he was never able to say no to any person who needed him, whether it was someone who needed help with his marriage, with complex family issues, or who was having difficulty in yeshivah or wasn’t even in yeshivah.

“I was once with him at a simchah and some girl came over to him and said, ‘Rabbi, do you remember you once gave a shiur on the concept of ‘covenant’ that you never finished?’ He sat down right there and gave a brilliant, hour-long shiur on all the meanings of covenant. When he spoke, you could practically transcribe and publish it word for word, that’s how coherent and polished it was.”

The Happiest People I Know

During the 11 years he spent in Eretz Yisrael in the 1970s and early 1980s, Reb Hillel pursued his first intellectual love, seeking out as many of the remaining mussar personalities from prewar Europe as he could locate, hoping to hear firsthand of the traditions and tales of a vanished world of the spirit and, of course, to learn mussar with and from them.

Sitting with him now, it feels as if these great men whom Reb Hillel knew intimately are there in the room with us, and I prod him to share some memories. “Once, during Aseres Yemei Teshuvah, I was standing in line in the post office with Rav Binyomin Zilber, the great posek, who was a talmid of Novardok. In those days before e-mail, the fastest way to communicate with someone was by special-delivery mail, and although this is a man who never wasted a second, he was waiting to get his special-delivery stamp so he could get a letter to someone asking mechilah before Yom Kippur. What possible offense he could have made against someone, I don’t know, but that was his perspective.”

In Tel Aviv, Reb Hillel sought out Rav Chaim Yitzchak Lipkin, a great-grandson of Rav Yisrael Salanter. His refined demeanor so clearly reflected the ideals of his elter zeide that Reb Hillel felt meeting him was “akin to standing before a mirror of history.” He showed Reb Hillel the original of the very last letter written by Reb Yisrael, just days before his petirah in 1883, to his grand-daughter, congratulating her on her engagement to a young talmid chacham named Reb Chaim Ozer Grodzensky — and advising her to make sure he was not only learned but of fine character too.

Reb Hillel was struck by the gorgeous, flowing handwriting, which bespoke a great serenity, reminding him how when Rav Yoizel Hurvitz met Reb Yisrael during his last years, he was so overwhelmed by the latter’s menuchas hanefesh that he decided to leave his textile business for a life devoted exclusively to Torah. Rav Yoizel went on, of course, to become the person we know as the Alter of Novardok.

For many people, all that the name Novardok brings to mind is the well-worn anecdote of a young mussarnik who seeks to eradicate his self-importance by entering a grocery store to ask if there are nails for sale, thereby bringing ego-deflating scorn down upon himself. Is there nothing more, I wonder aloud, to an approach to mussar that at its glorious pre-war height encompassed a network of over 70 yeshivos in Russia and Poland?

Reb Hillel’s knowing smile indicates that he, too, has heard the “nails in the grocery store” trope one time too many. “I would say more broadly that the mussar movement is unique in the great chasm that exists between the image and the reality. Regarding Novardok specifically, the image is of these extremely solemn, dour, unhappy people burdened by the unfathomable greatness of G-d and the unfathomable smallness of the human being.

“So, let me tell you what I have found,” Reb Hillel continues. “The happiest people I have ever known in my life, without any second choice coming close, have been the great people of Novardok I’ve known. I used to learn the Alter of Novardok’s sefer, Madregas Ha’Adam, with Rav Yitzchok Orlansky z”l in Yerushalayim, and most times I left with a stomachache from bouncing up and down on my chair with laughter as he’d explain the sefer’s words. His smile was so wide and stretched around his face, that all you saw were these narrow slits at the extremities of the eyes. Now, keep in mind that he lost his whole family except for one son in the Holocaust, he spent the war years in Siberia, and he came out of the war with his whole spiritual world annihilated. And he was the happiest person I’ve ever known.

“So you’ve got these images, and you’ve got the reality, but it’s the reality that counts, not the images. Whether people really went in to ask for nails or if that’s a myth, I don’t know. But let’s say, for the sake of argument that it did happen. What was the point of these exercises? It was to free the human being from all considerations that could possibly distract him from being happy as a created being of the Master of the Universe. And if there was nothing in life that bothered him, then there was nothing to be but happy.”

As our own growing, newly affluent frum community experiences the rise of a class of “adults at risk,” leading lives devoid of genuine spiritual content, and as we grapple with issues like runaway consumerism and the tyranny of technology, many people wonder whether these trends can be reversed and whether a renaissance of mussar might have a role to play in achieving that. But I can’t resist probing, or perhaps provoking, Reb Hillel on the question of whether mussar even still lives.

“Mussar seems to be an enduring casualty of the Holocaust,” I venture. “Chassidus recovered and is now burgeoning, and the yeshivos, some fared better than others. But mussar seems not to have really survived. Was it indeed a casualty of the war or did mussar never actually succeed on a grass-roots level?”

It’s a question Reb Hillel has long pondered. “True, it never grew into a mass movement as Reb Yisrael Salanter had envisioned, but it was still much, much bigger and thus was indeed a casualty of the war. And the question is why. I think the answer is that mussar is a lot harder to do, it’s much more demanding, and it has many fewer trappings. Although there’s certainly ‘music’ in mussar, it’s not the same as going for Lecha Dodi to a chassidishe shtiebel. It’s not a happy, ‘get up and dance and clap your hands’ music. It’s a music that serves the process of introspection.”

Regarding Novardok in particular, Reb Hillel observes, one of the reasons it didn’t survive is that it flourished in a climate very influenced by Marxism, which claimed there’s nothing more to this world than the material. So against that extreme, Novardok posited a dissenting reality, a spiritual extreme — that the spirit is everything.

“With a very well-defined enemy, Novardok could flourish,” Reb Hillel explains. “But as Marxism declined, the total clarity borne of that stark choice declined as well. And yet, it survives, certainly not in terms of numbers, but in influence, a lot of which is due to Rabbi Perr’s teaching. Institutionally it’s not strong, but there are people still following its path.”

But, he notes, the baal mussar is not concerned with whether the world is following his path or not. He’s not concerned with the sociology of his movement because by definition, he’s focused on the integrity of his own personality, behavior, and avodas Hashem.

“So if other people are doing it, great,” says Reb Hillel. “And if others aren’t doing it, that doesn’t relieve him of his responsibility one iota. Mussar is not out to win a popularity contest.”

The Way to Santa Fe

Rabbi Bulman. The Bostoner Rebbe. Rabbi Soloveichik. The masters of the mussar tradition. The range of influences and mentors that have formed Hillel Goldberg’s worldview and informed his works is unusually broad. And so, too, is the breadth of his own involvement in Jewish life: Here is someone who has written books published by ArtScroll that are highly popular in yeshivah circles, who sits on the editorial board of both Jewish Action — the OU’s quarterly magazine, and Tradition — the RCA’s intellectual journal, and is the published author of Hallel HaKohen, an in-depth study of the Biur Hagra, the cryptic glosses of the Vilna Gaon, on the laws of mikveh.

In truth, however, Reb Hillel’s influence doesn’t stop at the bounds of the Orthodox community, but extends beyond into the far larger world of non-Orthodox American Jewry. His concern for fellow Jews, which is embodied on a weekly basis through his journalistic stewardship of IJN, came shining through in what might be called the Saga of Santa Fe.

One day in April of 1986, a new face appeared in Reb Hillel’s shul in Denver, and mindful of the Bostoner Rebbe’s admonition to always greet newcomers with a warm shalom aleichem, he did just that. He and the visitor, Len Goodman, a resident of Santa Fe, New Mexico, who was in town on business, got to talking. Goodman spoke of a spiritual awakening in his hometown that had led a group of Jews to form a traditional minyan within the local Reform Temple Beth Shalom.

On the spot, Reb Hillel and a friend, Gilbert Jacobson, offered to host the group at a shabbaton in Denver. The event indeed took place that July, with Rabbi Rafael Grossman of Memphis’s Baron Hirsch Synagogue as guest speaker, and it was a huge success: Reb Hillel estimates that 17 of the 25 hours of that Shabbos were spent davening and learning. It was followed by another shabbaton, this one at the La Fonda Hotel in downtown Santa Fe, which also drew some 70 people from Temple Beth Shalom.

On Friday before the shabbaton, the Goldbergs and the Grossmans went to inspect the site where the minyan’s members had begun constructing a mikveh with their own hands for the benefit of the one couple among them that had committed to keeping taharas hamishpachah. They gazed, dumbstruck, at the nine-foot hole, until Rabbi Grossman spoke up: “This is the Western Wall of the Western Hemisphere.” That Motzaei Shabbos, following another intense Shabbos experience, Rabbi Grossman spent three hours convincing the group’s members to install a mechitzah in their separate minyan at the temple.

The group’s path to acceptance in Santa Fe was assisted in no small part by Temple Beth Shalom’s own clergyman, Leonard Helman. As Rabbi Goldberg wrote following Helman’s passing in 2013, “It was he who thought it was just fine that a group of his congregants decided they wanted to be traditional. The word ‘tolerate’ did not exist in his vocabulary. He did not ‘tolerate’ this unusual development; he welcomed it… When the group formally became a kehillah, taking the name Torah Bamidbar, Len Helman said, ‘I’m joining. Not as rabbi, but as a member.’”

Slowly, the minyan’s members moved toward full observance, with Reb Hillel spending his evenings on the phone to Santa Fe, teaching Torah and helping organize a community. He brought the Bostoner Rebbe to Denver for a shabbaton with the group and arranged for numerous rabbinic couples, such as Rabbi and Mrs. Emanuel Feldman of Atlanta and Rabbi and Mrs. Yitzchak Wasserman of Denver, to spend a Shabbos — or longer — in Santa Fe, all without remuneration.

By 1988, the Torah Bamidbar community had a full-time rav, Rabbi Shlomo Goldberg, along with a mikveh and a one-room day school comprised of nine children spread across eight grades. Within three years, however, most of the kehillah moved on, to Denver and Eretz Yisrael – one of the group’s original members is now a great-grandfather whose grandson is a rosh kollel in Ramat Beit Shemesh — although there still exists today a group of shomer Shabbos Jews in Santa Fe.

Scratching the Surface

By now, his outreach work in Santa Fe and Jerusalem are a distant memory, but for Rabbi Goldberg, the imperative to educate and elevate fellow Jews never ceases, it just changes form. When he published his work on hilchos mikvaos several years ago, it was the culmination of eleven years of study, followed by six years of writing. Now he’s nearing completion of a second sefer, which has been over eight years in the making, this one focusing on the Vilna Gaon’s commentary on another complex siman in Yoreh Deah dealing with the concept of sfek sfeika.

Fulfilling as it has been to produce these works, he keeps his achievements in perspective: “People say, ‘So you’re an expert in the Biur Hagra,’ and of course, I’m not at all. I now have some knowledge of what the Gaon wrote on two simanim in Shulchan Aruch. Who knows what’s going on in the hundreds of other simanim? Only people like Rav Moshe Feinstein and Rav Elyashiv can be experts in the Biur Hagra; the rest of us are just scratching the surface.”

But like his father before him, Reb Hillel is always working on more than one thing at a time, and so he’s readying an English-language volume for publication later this year, on a topic that’s very dear to him: Shabbos. Tentatively titled Bringing the Week into Shabbos, Bringing Shabbos into the Week, one of its goals is to help readers to allow Shabbos to permeate their consciousness throughout the week. He hopes it will help motivate people to finish many Shabbos tasks early, thereby entering into Shabbos with a gradual increase in kedushah in place of the all-too-common last-minute mad rush. The book opens with a poem about Shabbos Rabbi Goldberg wrote some 30 years ago which he says “can be found on people’s refrigerator doors around the world.”

As our time together comes to a close and I leave his office, Reb Hillel’s next appointment enters. A young man, secular in appearance yet who recently discovered mussar, is here to consult him on what path in that discipline is most appropriate for him.

Another Jew to meet, to teach, and to learn from.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 655)

Oops! We could not locate your form.