Strapped for Life

Dr. Yehudah Pryce, gangster turned Orthodox Jew, helps young people who’ve been arrested put their lives back on track

Photos: Levi Lehman

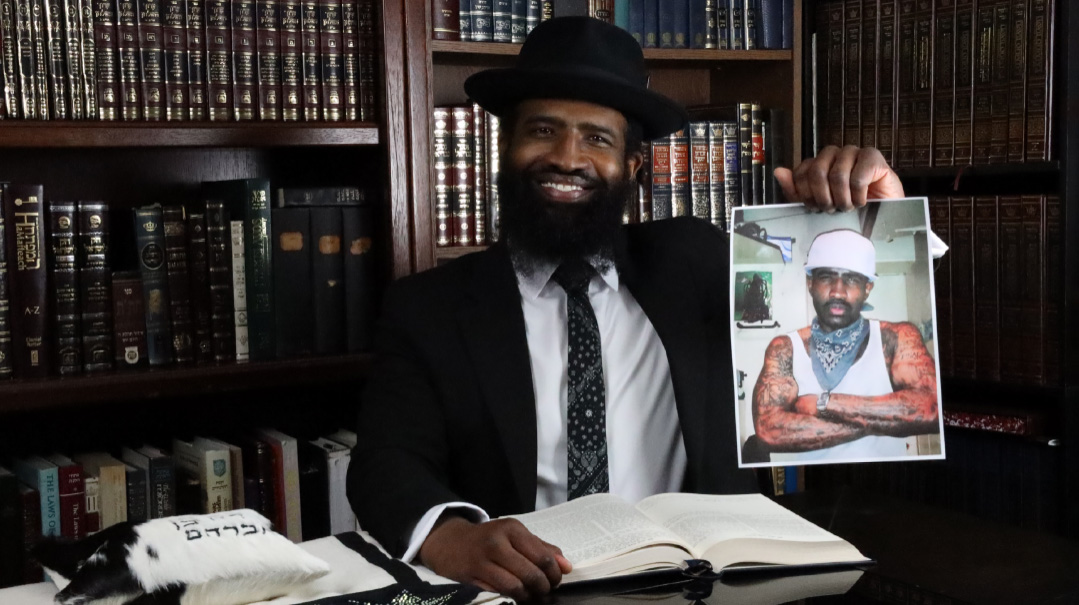

The first thing that grabs you is the sweetness of his smile. You can’t miss the crinkling of his eyes and the openness of his face, which radiate warmth and refinement and an eagerness to engage. Bearded and besuited, he removes his black hat and deliberately places it on the table in front of him like a rebbi settling into shiur. Meet Yehudah Pryce: dedicated Jew, devoted family man, social worker — and former violent gangster.

Because that’s exactly what he was for the first three decades of his life.

Raised by his Sri Lankan mother and Caucasian stepfather in a lower-middle-class town in Orange County, California, populated by mostly Mexicans, Asians, and whites, the dark-brown skin that Omar Pryce inherited from his biological Jamaican father was a rarity in his town, his school, and even his home. From a very young age, he felt like a stranger in his own world.

“By the time I was eight, I would lie awake at night pondering who I was. I struggled with the feeling of not fitting in,” Yehudah says today of the Omar of his childhood. “I was bullied and harassed for being black, and I absorbed the message that there was something inherently wrong with me. I saw my father very inconsistently, and so I had no black role model to negate that message and set a positive example for living a moral and successful life. Well-meaning people would tell me I’m not really black since my family was white — my three half-siblings are light-skinned — and I’d ruminate on that, but it left me even more confused.”

Eventually, young Omar concluded that the rules of society were made up by people.

“They have no value in and of themselves, so I have no obligation to follow them,” he remembers thinking.

Thus, unmoored from moral restraint, his downward slide came so early and fast — by eight he was stealing baseball cards from grocery stores and getting into physical fights in the neighborhood — that by fifth grade, he says, he already turned his life back around. But his good behavior didn’t last long, and by the time Yehudah/Omar was 13, he was a full-fledged gangster, carrying guns, selling drugs, fighting, and hanging out with gang members.

For a kid with a poorly defined sense of identity, the lure of belonging to a group exerted a gravitational pull.

“Being in a gang makes you part of an extended family that will do anything to protect its own. You know exactly what you need to do in order to belong. As long as I carried out gang exploits, I had an identity that couldn’t be challenged,” Yehudah explains.

“I discovered that the black macho persona earned me respect, power, and even fear. It was considered cool to be someone who broke the rules, and at parties and school events other kids looked at me with awe — I’ll be honest, it was a fun life. And crazy as it sounds, I showed up at school every day, took honors classes in high school and even some AP classes. My mother and stepfather did their best to rein me in, but nothing stopped me — if I was grounded, I’d just sneak out the window.”

Yehudah worked hard to establish a reputation of bad guy in the gang world, just like anyone determined to excel in their field. Being arrested was proof he’s made it – until he was gripped by a need to have a real relationship with his Creator

Gang Mentality

The underworld Yehudah entered is an alternate universe, complete with its own set of rules, codes of conduct, and cultural norms.

White and Hispanic street gangs have a somewhat organized structure, Yehudah says, and while most crimes are done independently, directives can go out from the top for individuals to commit certain “actions.” Black street gangs, on the other hand, generally lack a formal structure. Crimes aren’t assigned, but members utilize the gang network to facilitate crimes on their own. In all gangs, if a member doesn’t take an expected action — such as retaliating for an act of violence against a fellow gang member — at the next gang meeting he can expect to be disciplined, such as by being “jumped” (beaten) by his buddies.

In Yehudah’s home state of California, the two largest black gangs are the Bloods and the Crips. Crips are subdivided into many factions and sub-factions, typically by neighborhood (e.g. Long Beach Insane Crips), and sometimes down to the street they come from, with their street number referenced in their name (e.g. 52 Hoover Crip Gang).

Still, while all Crip factions share a common culture, they aren’t necessarily in alliance. For example, Neighborhood Crips and Gangsta Crips are mortal enemies. Politics are rife between factions, and grievances are marked in permanent ink: If someone on 60th Street is killed by someone on 83rd, the rivalry is handed down forever, and either side can go out anytime and “put in work” against members of the other.

Gangs utilize colors, numbers, and symbols to identify themselves. Crips wear blue, Bloods wear red. Neighborhood Crips utilize hand symbols in the form of the letter N and wear caps that say North Carolina, which has the same initials as their name. Some gangs have taken ownership of certain numbers, which they use in graffiti.

As a young teenager, Yehudah first developed ties with neighborhood gang members before branching out to gangsters throughout Orange County. He eventually identified most closely with the South Central L.A. Crips, which he considered his “criminal home base,” but he was never initiated into any particular faction.

“I took pride in being a free agent — being a cog in a machine wouldn’t cut it for me,” he says.

His independence was so central to his identity that he imprinted it down the length of his arm in a tattoo that reads “One Man Gang.”

Yehudah/Omar worked hard to establish a reputation of notoriety in the gang world, “just like anyone else trying to excel in their particular field,” he says. And excel he did: He was arrested multiple times throughout his teens for crimes like strongarm robbery and selling drugs, and he did a few stints in juvenile hall (prison for underage offenders).

By 18 he settled into his particular niche: robbing drug dealers, something he thought of as a “safer” crime since dealers would be unlikely to call the cops on him.

“I’d tell my network to send out the word that I was available to buy drugs, and the guy who found me a seller would get half of what I netted. That seller would become my next victim,” he says.

Yehudah averaged one robbery per week, working meticulously to build his résumé and establish himself in his “career.” The occasional house raid by law enforcement with drawn guns and drug-sniffing dogs was a small price to pay.

Highly intelligent and creative, Yehudah got particular satisfaction from devising clever feats. “In one incident, while out on bail, we had no time to plan, and no gun,” he recalls. “My friend was posing as a drug buyer. The seller was a gang member and presumably armed. I directed my friend to tell the seller that he wanted him to come into his car and show him the goods. The seller got in the car and handed him the drugs to check out, and my friend said, ‘Looks good, let’s go inside and finish the deal.’ As soon as the seller got out of the car, my friend locked the door and sped off, drugs in hand.”

Why commit serious crimes on bail, if the repercussions could be disastrous? “Simple,” Yehudah says. “I had a constant need to feed my identity. If I wasn’t out doing crimes, I couldn’t be a gangster. And since I was headed to jail where gangs rule, I grabbed every chance I could to gain more respect in the gang world.”

In the underworld, intimidation is the fast track to respect, and Yehudah describes it as an art form. “The key to instilling fear is to make your enemy believe you’d be willing to shoot them anywhere at any time, so sometimes I’d shoot right on the street in broad daylight. But I always made a concerted effort not to hit anyone, because that would invite trouble — so I’d shoot toward gang members, but make sure to miss.”

Listening to this mild-mannered man shining with Yiddishe chein detail his crimes is strikingly incongruous. Surely, he had a conscience?

Ever the gentleman, Yehudah thoughtfully considers the uncomfortable question.

“Most of my violent crimes were against drug dealers or other gang members, whom I considered fair game for being criminals themselves. Violently robbing innocent civilians wasn’t my thing — if the need arose, I’d do what I had to, but I wouldn’t feel good about it. I did some commercial robbery and credit card fraud against civilians, but I found ways to justify it to myself. I actually considered myself a man of integrity, loyal to the values I proclaimed: Never snitch on a friend to police, always defend your friend if he’s facing danger, never back down from confrontation if your honor is being disrespected, never hurt women or children. But the yardstick I measured myself with were the values respected in the subculture I was part of, not those of the wider world.”

One might expect this kind of articulate, bookish language from the lectern of a sociology professor, but it induces a double take when coming from a former longtime street criminal. But Yehudah, clearly of gifted intelligence, points out that he always maintained good grades and even skipped a grade in school, has a diploma from a respectable high school, and read incessantly in prison.

Into the Slammer

February 14, 2002 marked the beginning of the end of an era in Yehudah’s life — but he didn’t yet know it when he began his “workday” directing a crime from behind the scenes.

One of his buddies lived with some drug dealers, and the plan was for him to leave the apartment door open at a designated time. Two armed accomplices in ski masks would burst in, hold everyone up, and steal the drugs. When the police would come, his buddy would play innocent victim.

“But my friend wasn’t the brightest, and when the police came, he quickly became a suspect,” Yehudah says. “He was arrested, and identified me as an accomplice. Later, he was offered a sweetheart deal to turn State’s evidence against me, and he did. Police raided my parents’ home and found me with a ski mask, a loaded gun, and a mini-Uzi.”

Yehudah spent the next three years in county jail while his case was pending trial. It was here that he got his first taste of the deep hostility between races that permeates prison, incomparable in degree to anything in the outside world.

“In prison, if someone of race A attacks someone of race B, everyone in race B is expected to join the melee and attack members of race A,” he explains. “One day, there was a fight between a white man and a black man. That night, when everyone was sleeping, a group of white inmates set out to retaliate. They stabbed every black person they could find while they were asleep in their beds. I, too, was stabbed.”

While in county jail, Yehudah developed, in his words, a “ridiculous strut,” that broadcast to everyone around him, “Steer clear. I’m big, bad, and dangerous.” Physicality is a key component of survival in prison, and he began working out daily, something he’d continue throughout his years in prison, so that he could “peacock” (showcase one’s muscles) with the best of them. He organized “Friday Fight Nights,” in which inmates engaged in fighting contests with each other, and he was usually one of the last men standing.

Yehudah was eventually convicted and sentenced to 24 years in prison: four years for robbery, ten years for a gun enhancement (time added for the use of a gun in the commission of a crime), and ten years for a gang enhancement (time added for a crime done to benefit a gang). He was 22 years old. His reaction to his sentence: a moment of despair, quickly covered up by pride. “If I got a 24-year sentence, I must be a real gangster,” he remembers thinking.

“I was put into a paper jumpsuit, shackled at the ankles, waist, and wrist, and put on a bus for the 14-hour ride to Pelican Bay State Prison, a maximum-security prison for the most dangerous criminals out there,” he says. “But I didn’t feel fear — it was the kind of crowd I was used to. I was all about authenticity, and being here meant I was actualizing my potential as a gangster.”

That doesn’t mean he wasn’t preoccupied with the fact that his life was in constant danger. He’d hear skinheads in the next cell sharpening knives to use against blacks, and his mental calculations went like this: “I really need to sharpen a knife for myself. But if it’s found, I’ll get in serious trouble. If I actually use it, I’ll get life in prison. And if I’m really unlucky, a corrections officer will catch me using it and shoot me on the spot — prisoners have died that way. On the flip side, if I don’t sharpen a knife, I have no way to defend myself and can also end up dead.”

Inmates would make knives by sharpening pieces of metal from a stolen bookshelf in the school area, for example, or by melting down and sharpening a piece of plastic. Matches, of course, were contraband, but prison is a seedbed of ingenuity, Yehudah says: With a lead pencil, paper clip, piece of wire, and an outlet, you can create a spark; with toilet paper or a cotton ball, the spark can become a flame; with a piece of lard stolen from the kitchen, the flame can light a candle.

Prison life is dominated by racial divisions. Every inmate belongs to a “car,” the group of people you’re in alliance with based on common race.

“Anything could set off a fight in the yard, from a drug debt, to a perceived slight, to which race is allowed to use which exercise bars in the yard,” Yehudah says. “Before you know it the whole place is at war, because no one wants to be disciplined for not defending their own car.”

In maximum security prisons like Pelican Bay, prisoners are in their cell all day, meals included, other than one-and-a-half hours outdoors for “yard time” a few days a week, an hour in the communal dayroom a few days a week, and 15 minutes a day for showering (reduced to five minutes every three days when the prison is on lockdown). But even so, gang meetings, drug deals, and contraband commerce all manage to abound.

“Business takes place in the back of the chapel during services, on the nurse line, or in the law library, although in maximum security prisons, permission to visit these places is given sparingly.”

Limited access to goods creates a robust black market, and enterprising inmates can carve out profitable niches for themselves.

Yehudah found his as a middleman in the smartphone market: inmates smuggled the devices in, and he’d find buyers, pocketing a nice cut. He paid $500 for his first phone in 2010, a prepaid model worth about $30 outside. But dogs trained to sniff for phones are never far away, and the stakes are high if caught: solitary confinement and/or 90 extra days in prison and/or loss of visiting rights. Owning a phone meant a never-ending game of hide-and-seek.

“My favorite method was to wrap my phone in the saran wrap that came with my meals and hide it in a glass jar of jalapeno wheels I’d buy in the canteen,” Yehudah says. “I’d make sure that all inner surfaces of the jar were covered with jalapenos, giving the illusion that the jar was full. I’d also thickly layer the top of the jar with jalapenos in case the searchers opened it.”

From Crook to the Book

Yehudah assumed he’d die a gangster, but seven years into his incarceration, at age 27, something interesting happened.

“Religion wasn’t part of my life before prison, although I identified as a Christian,” he says. “In prison, many people turn to religion as a crutch to survive, and that seemed weak to me — I wanted to survive with just my wits and inner strength. I had a real aversion to organized religion.”

To him, religion was, as Karl Marx famously described, the opiate of the masses, but it would be inauthentic to reject it without knowing what he was rejecting, so Yehudah felt morally compelled to study various theologies.

He started with different sects of Christianity, read the Koran cover to cover, delved into Buddhism — and found ways to reject them all. He considered himself an agnostic deist, acknowledging a Higher Power but unable to prove G-d exists or that He related to Yehudah personally.

Pelican Bay would bring in ministers of different religions to lecture, and, confrontational guy that he was, Yehudah amused himself by showing up and challenging them.

A lawsuit a few years prior resulted in a law that stated that if Judaism is an inmate’s “sincerely held religious belief,” he has the right to be in a prison with a rabbi on staff; if his current prison didn’t have one, he was entitled to transfer.

Pelican Bay did not have a rabbi on staff.

“Suddenly you had white supremacists with swastika tattoos claiming to be Jewish, because everyone wanted to transfer out of Pelican Bay — it’s the worst of the worst,” Yehudah says.

This was an issue for Pelican Bay — it is difficult to disprove someone’s claim to a ‘sincerely held belief’ — so in 2010 the prison hired a Reform rabbi.

This, despite the fact that Yehudah wasn’t aware of a single Jew there.

“So this rabbi gives his first talk, and there I am in the chapel ready to argue. Judaism is the basis for other religions, so it was an important one for me to knock out. I said, ‘You’re telling me I have to believe all those stories from the Bible?’

“He responded, ‘Whether you believe it or not, it’s indisputable that Judaism has worked for the Jews — they’ve maintained their language, culture, and identity for thousands of years, despite annihilation attempts nearly every century.’ ”

Yehudah had just finished reading Mein Kampf, which clearly demonstrated the rabbi’s point; it resonated deeply, and he wanted more. The rabbi gave him To Be a Jew by Rabbi Hayim Halevy Donin, followed by many other books. That Judaism is the only religion with a mass revelation meticulously transmitted from generation to generation was a particularly powerful concept for Yehudah.

He also read that the Jews are covenant-bound to the Creator of the Universe.

“When reading Mein Kampf, I kept waiting to discover a valid reason for Hitler’s Jew-hatred, but there was none. Now it made sense to me — if a group of people has a special covenant with G-d, I could see other people having a problem with that. And if this covenant is the purpose of the Jews’ existence, then the fact that they’ve supernaturally survived despite all the persecution is proof that the covenant is true,” he says. “But logic aside, Judaism just spoke to my neshamah. None of the other religions I studied made me feel anything — but with Judaism, I was stirred emotionally.”

About a year before meeting the prison rabbi, Yehudah had received a letter from his teenage sister in which she expressed her anger toward him for the pain he caused the family. As he stewed this over in his cell day after day, the life of violence and crime began to lose its luster.

“I realized we were all a bunch of losers,” he says, and he was gripped by a determination to rectify his life. Judaism came along at just the right time, offering him concrete steps to connect with G-d, and through that, to perfect himself as a person.

His transformation was swift and all-in: Confined to his cell at least 22 hours a day, Yehudah read one or two books from the chapel library daily; within a month of his initial meeting with the rabbi, he knew enough about Judaism to decide to convert.

“I taught myself Hebrew, and immediately memorized the Amidah so if I ended up in lockdown, I could say it by heart.”

Shortly after his introduction to Judaism, Yehudah was transferred to a level-3 (lower security) prison, which allowed for greater freedom of movement. (If an inmate stays out of trouble, his security level automatically drops with time.) Sneaking in phones was easier here, and Yehudah managed to obtain a smartphone. From that moment on, he spent most of his time online researching Judaism, hungrily absorbing as much as he could. (He also met his future wife Ariella online at this time.)

Two years into his Jewish journey, Yehudah knew he’d convert as an Orthodox Jew — despite never having laid eyes on one in his life.

“I understood that humans couldn’t be the arbiters of transcendent truth, as the Reform would have it,” he says. “If morality matters, it must come from a Source. My neshamah was drawn to having a relationship with the Creator, and mitzvos give me a tangible way to nurture that connection. The communal aspect of Judaism wasn’t part of the equation at all, as I’d never experienced it.”

He bought a tallis from the chapel clerk, ordered tefillin from a Judaica website, and started putting them on daily.

“At one point I shared a dorm-style room with 90 inmates. Surrounded by skinheads and people shooting up heroin, I’d bind myself to Hashem,” Yehudah says.

But as much as white supremacists loathe Jews, Yehudah didn’t feel threatened. Despite interracial tensions, inmates of different groups are polite and respectful to each other in order to avoid widespread conflict; everyone knows that whoever starts a conflict will face discipline by the leaders of his own car.

Yehudah performed every Jewish ritual he could, but he made sure to do one melachah on Shabbos, as required of non-Jews by halachah.

“Prisoners typically have a set of better clothing reserved for when they have visitors, which they buy from the laundry,” he says. “My visiting clothing consisted of an ironed button-up shirt, jeans, and a pair of polished boots — all desirable items and hard to come by — and this became my Shabbos wardrobe.”

For the seudos, he’d prepare a pot of instant rice and beans on Friday to eat warm that night and cold for Shabbos lunch (he didn’t have a blech), and he’d make Kiddush on a grape-powdered drink.

“It blew everyone’s minds that I wouldn’t touch my phone all Shabbos,” he says. “This was all so far-out that everyone started calling me ‘Shabbat.’ ”

Yehudah’s first visible shift from tough-guy bravado came when he donned a yarmulke. Soon after, he dropped his strut, and he continued to mellow from there — although he had to maintain a certain level of external toughness so as not to invite bullying and harassment.

Everyone around him scoffed: You think the Jews will accept you with your corrupt past and tattoos up your arms?

“I figured, if I was formerly dedicated to a lifestyle that was malicious and dangerous, I can certainly be dedicated to a way of life that connects me to the Ultimate Truth — even if I’m not accepted,” he says.

But it goes beyond that: Yehudah struggled his whole life with his identity, endangering himself daily to maintain a certain self-image. And he dropped it in an instant to adopt, in his words, “the most precarious identity possible”: that of a Jew with a completely foreign worldview and sense of morality, while not being one or even knowing one.

“I did it anyway, out of love for Hashem,” he says simply.

When the opportunity arose, Yehudah made a clever move that catapulted his spiritual development in ways impossible for most inmates: He secured the position of Jewish chapel clerk, working under a Reform rabbi. (He held the job for six years, earning 11 cents an hour.) While he was responsible for things like preparing program notices, organizing the chapel library, and eventually running Jewish-themed groups from a prison curriculum, there was a huge side benefit. “Inmates are allowed to own up to ten books. Now, not only did I have the entire chapel library at my daily disposal, I was also able to order books for the library, and I used it to great advantage.”

Yehudah ordered the Sapirstein Edition of Rashi on Chumash, a set of Mishnah Berurah, as well as other books on Judaism.

“Books ordered for the library had the added perk of not getting their covers chopped off, which is what happens to hard-covered books ordered by inmates, in case they conceal weapons,” he explains.

Starting Over

Thirteen years into his 24-year sentence, in 2015, everything changed. A legal ruling in California stated that the overcrowding in prisons constituted cruel and unusual punishment, and prisons had to lower their populations or the federal government would step in. Any inmate who had committed his crime under age 23 was suddenly eligible for early parole.

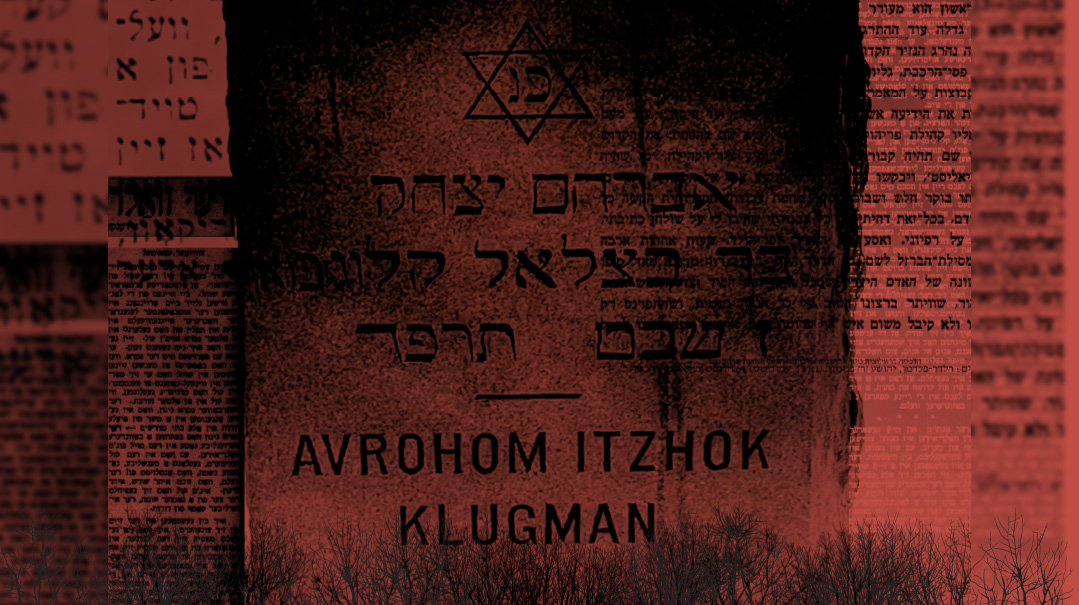

Knowing his release was imminent, Yehudah wrote a 14-page treatise called “From Juvenile Delinquency to Judaism,” detailing who he was and why he wanted to become Jewish.

He googled “Orthodox Rabbi Orange County” on his contraband phone, and Rabbi Yisroel Ciner in Irvine popped up.

If Irvine is the home of Orange County’s Orthodox Jews, then that’s where I’ll go, he thought, and he sent his treatise to Rabbi Ciner. (Yehudah didn’t want the locals to be scared when he showed up. He didn’t know it at the time, but Irvine is home to many geirim of varied backgrounds.)

“Rabbi Ciner responded that they’d welcome me with open arms,” Yehudah says.

He began looking online for post-prison career ideas (“I figured working in a bank was off the table,” he says). At the time, he was successfully running large groups for inmates on different areas of self-development using prison-established curricula, and it occurred to him that perhaps he was already living out his calling. Yehudah decided to become a social worker.

On October 22, 2018, after sixteen years in prison, Yehudah was released; he was 35 years old. He entered prison never having sent a text message, and emerged 16 years later with a career, religion, and soon-to-be wife, all enabled, in part, by the phone in his pocket. It was a completely new world, and it felt totally surreal.

“A few weeks after I got out, I attended my first-ever Torah class,” he recalls. “Learning Torah in a real shul, with a real Orthodox rabbi, alongside other holy Jews, brought me to tears.”

But freedom poses its own challenges, Yehudah says. Everyone in prison has big dreams of things they’ll do once they’re out, but when it’s time to execute those plans, they often become overwhelmed and paralyzed. Because Yehudah had presented the parole board with a detailed plan for his immediate future in order to qualify for early release, he had a concrete road map to follow.

Within a few weeks of his release, while living in a halfway house in Los Angeles on parole, Yehudah submitted his geirus application to the Rabbinical Council of California. The RCC has received many applications from prison inmates over the years, for all kinds of reasons — from wanting to get kosher meals (apparently an upgrade) to thinking it’s cool — but they invariably go nowhere.

“Yehudah’s application was immediately distinguishable from the typical prison application,” says Rabbi Avraham Union, dayan of the RCC. “He was clearly a brilliant fellow, and his answers were well-written, thought-out, and introspective — it was a very worthy read. We viewed him as a promising candidate, albeit one with flashing yellow lights because of his remarkable background. But every step of the way, Yehudah proved himself to be sincere, driven, and willing to do whatever it takes.”

But though Yehudah wanted to settle in Irvine, the $10.50 an hour he was earning as a part-time dishwasher wouldn’t allow him entry to a city whose median home sold price is close to $2 million.

“And then out of the blue, a Breslover chassid in Irvine heard about me and offered to rent me a room in his apartment at an affordable rate. I not only gained a place to stay, but living with him gave me a fully immersive experience in frum living, which was invaluable,” he says.

Yehudah joined the community — which welcomed him warmly — in May 2019, and after a Covid-induced delay, he completed his conversion the following June. A decade-long process reached its culmination as Yehudah ben Avraham Avinu emerged from the mikveh. In all that time, he didn’t waver even one minute.

“As I told the beis din, I know I’m aligned with emes, and nothing can keep me away,” he says.

“When I stepped out of the mikveh, the first thing Rabbi Union said to me was, ‘It’s daytime, now go put on tefillin.’ So I got in my car, drove to a side street for a little privacy, got out, and laid tefillin. For the first time, I tangibly felt part of a holy covenant with the Creator of the Universe.”

The name Yehudah chose for himself is the perfect expression of his positive outlook in prison, where he was grateful for the wherewithal Hashem granted him to cope with prison-related stressors, and later, for the way other challenges smoothly fell into place.

“From my early parole, to finding a community that made me feel so welcome, to the RCC’s quick acceptance of me (they’re known to be tough gatekeepers), to my wife moving from Canada to marry me (I wasn’t exactly the ideal applicant) — I wanted my name to reflect my thankfulness for all of it.”

Yehudah’s family was supportive of his conversion — his mother had converted from Islam to Christianity, so changing religions wasn’t a new concept for them, and in any case, strange religious customs are a big step up from house raids with guns and dogs.

“They see that my actions and philosophy are worlds away from where I was before, and they’re proud of who I’ve become,” Yehudah relates. “Whenever my mother she sees a frum Jew, she runs up to them and tells them that her son is part of the same club.”

She’s not the only one impressed.

“Yehudah is a real mevakesh,” says Rabbi Ciner. “This guy just showed up out of left field, and he is so knowledgeable and cares so much.”

He describes how Yehudah serves as a volunteer mashgiach for his shul’s kitchen. “Just yesterday, he texted me a sh’eilah about kli al gabei kli on a hot plate,” Rabbi Ciner relates. “Seeing his commitment to the smallest details wakes us all up.”

What Rabbi Union finds most striking is just how much Yehudah relishes his Jewish identity.

“A few months ago, close friends of his — a family with six kids — converted to Judaism, and Yehudah came to L.A. to accompany them to the mikveh. His excitement at their joining Klal Yisrael lit up his face.”

Just eight weeks after converting, Yehudah married Ariella. Today, he spends his days helping street kids develop their best selves in his capacity as social worker, and she does the same with their young brood at home.

Yehudah is happy to share his own story, but he prefers to keep his family out of the limelight. What he does share is that his life experiences inform his parenting every day: Feeling disconnected from both his father and stepfather as a child set him up for failure, so he showers his own kids with heavy doses of love.

With his former fellow inmates’ words still ringing in his ears, one of the biggest surprises for Yehudah was just how wrong the scoffers actually were.

“Back in prison, for years they convinced me I’d never be accepted by the Jewish community, so it’s still a little hard for me to believe that schools and shuls fly me across the country to speak, and magazines want to publish my story. I’m amazed at the degree of warmth and love I’m met with wherever I go,” he says.

Paying It Forward

Today, Dr. Yehudah Pryce DSW, MSW, serves as Senior Director of National Mental Health and Well-Being Programs at Defy Ventures, a national non-profit that offers personal development and career readiness programs for people coming out of prison. He also works with the District Attorney’s office (“The same guys who argued to the parole board against my early release, claiming I’d be a threat to society,” he says) in a program for youth who have been arrested, helping them get their lives back on track.

Yet the key to his success goes much beyond the doctorate in social work he earned over the last three years.

“I’m what’s known in the field as a ‘credible messenger’ — my message is more readily absorbed because I’ve been through it myself,” Yehudah says.

His messaging points inward as well. He shares an ideal from Shaarei Teshuvah: Find favor with Hashem by doing good with the very same instruments you’ve used for sin.

“Hashem has given me the opportunity to rectify on some level the damage I did to society, and this is a key part of my teshuvah,” Yehudah says.

As meaningfully productive as his days are, the constant motion leaves Yehudah nostalgic for at least one aspect of prison life. “I miss having as much time as I want to focus on learning,” he says. But his learning schedule is hardly paltry: He’s part of an intensive, multi-year online hilchos Shabbos program, learns Gemara with a chavrusa five days a week, studies the weekly parshah in depth, and learns with a small group of frum black converts via Zoom (a breakaway of an 89-member WhatsApp chat comprised of frum black geirim around the world). To top it all off, he’s teaching himself Yiddish.

As far as Yehudah has come, it’s a concept he discovered in the infancy of his Jewish exploration that remains his guiding principle today: Shivisi Hashem l’negdi samid — I have set Hashem before me always.

“This had a big impact orienting me during my incarceration — it was at the forefront of my transformation — and it has an even bigger impact today. As I walk around as an obvious Jew, I’m always conscious that my actions reflect Hashem’s Torah and His People, and I try to live up to that weighty responsibility,” Yehudah says.

That’s one directive the world’s holiest gangster is still happy to execute.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1008)

Oops! We could not locate your form.