Gifted

But then there are the gifts that don’t fit into shoeboxes, or shelves, or even albums

When the gifts started to trickle in, I gave my son a shoebox and said, “Put all the checks in here, and keep a list of who gave what.”

Which he did rather meticulously, tallying up his growing collection with joy.

And just this week, yet another Ikea bookshelf graces our home, right outside the boys’ bedroom. Now we can unpack the impressive Shas he got from his aunts and uncles; the red Avnei Miluim; the gleaming volumes that stand upright on the still dust-free shelf.

But then there are the gifts that don’t fit into shoeboxes, or shelves, or even albums.

Like the gift of a great-grandfather attending his bar mitzvah, imparting a message of love and faith, of past and future.

How much is it worth to have a Yid in his nineties — once flogged and beaten on his head so badly that his hat size is off the charts — telling the generations around him about the final moments spent with his father?

“…And my father stood there and said to me, ‘Blahb a Yid!’” His voice cracks. I wave the waiters away, telling them to hold off with the chopped liver for a few more minutes. A brave cousin stands guard at the door, keeping the sweetest little great-grandchildren out.

“And a few years ago, some nonreligious college students had to write about the Holocaust, and they found me. They asked me, ‘How could you have remained religious after everything you went through?’”

He stretches out the how and his voices takes on a gentle tone. We know the inflections already; we’ve heard it so many times — at Chanukah parties, previous gatherings and simchahs, and midweek visits. We know the punch line, too.

“And I told them, ‘I couldn’t sit shivah for my father. I couldn’t even say Kaddish on his yahrtzeit. How could I not listen to his last words?’ ”

He gives his sideways shrug, and we sit in silence, the bearded men, the moist-eyed ladies, the pensive teenagers. The hush in the room is palpable, no matter how many times we’ve heard it.

He has many stories, our zeidy, about his years as a yeshivah bochur in Hungary, about not eating treife meat in the camps, about his escape from Communist Budapest in 1956.

But he has his favorites.

Like his encounter with a holy rebbe, when he was just 15. As an ally of Germany, Hungary had ordered its citizens to give all wheat above the quota of 100 kilo per person to the Germans, literally taking bread out of the mouths of its people.

A small group operated a black-market bakery in Satmar, not far from Zeidy’s hometown of Fulest. One day, a Hungarian official raided the place and, uncovering the clandestine activities, set out to bring justice to these “criminals.” As Zeidy’s father owned the industrial mixer, he was arrested along with the group of Yidden involved. The frightened Jews sat in prison, fearing an unusually harsh verdict, as they knew their crime would be showcased as a dire warning to others.

Someone urged Zeidy to go to the heiliger Chakal Yitzchak of Spinka, in the not-too-distant town of Selesz.

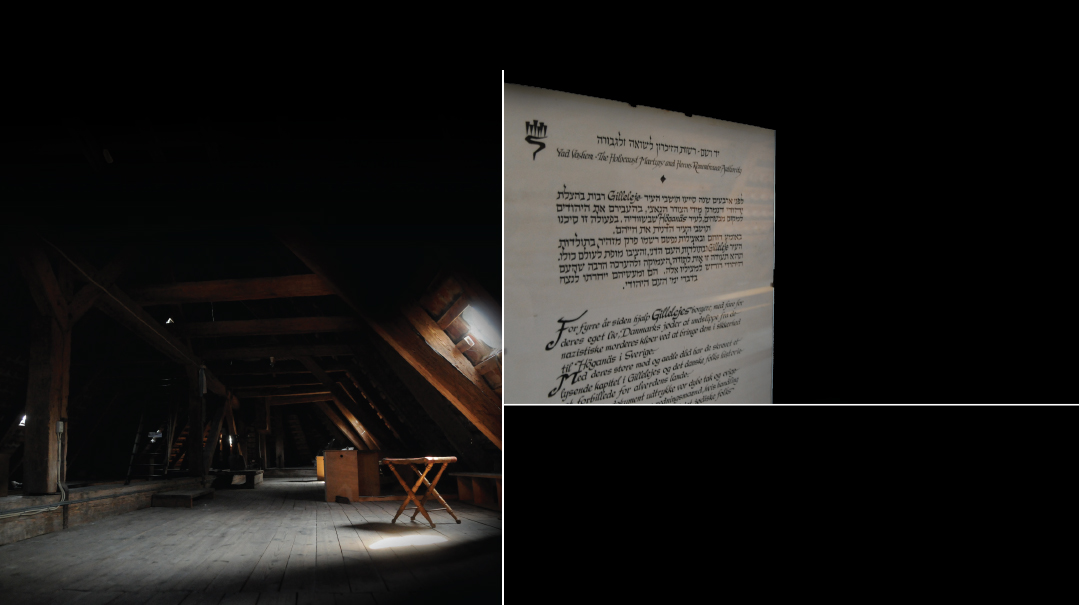

Zeidy remembers the dimly lit room at 11:45 on that Monday morning, and how the Rebbe sat on a hard bench. Zeidy told him about his father and the others, held in jail on serious charges.

Zeidy’s voice gets subdued, almost awed at the memory.

“The Rebbe put his head down for a long few moments. Then he picked it up and looked at me.

“‘Avrum Yitzchak ben Rivka vert frei. Alleh veren frei.’ [Everybody will be freed.]

“I told him, ‘There was a goy among them, who carried out the transactions.’

The Rebbe put his head down for another two or three seconds. Then he picked it up and said, ‘Der goy vert oich frei.’ ” [He will also be freed.]

And true to the Rebbe’s word, the official inexplicably dropped the case and set the group free less than three hours later.

There are not too many people left today who saw the horrors of the war, who saw the heilige rebbes of the past generation, who lay tefillin on disfigured heads and marked arms.

Even if Zeidy’s voice is now weak and frail, his message at a family simchah is resounding. No shelf can possibly store that gift, no fat check can rival its worth.

I hope my son, in his cute little narrow-brimmed hat, appreciates that.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 876)

Oops! We could not locate your form.