Through My Lens

| April 16, 2024Abe Kugielsky’s camera goes to Brooklyn to highlight life and remove barriers

Photos: Hasidiminusa

Passionate about the color and beauty hiding in the black and white shades of chassidish life, Abe Kugielsky takes to Brooklyn streets and gets behind the lens of his camera to document the lives of a community he loves. Zooming in on the highlights and humdrum moments of life in these parts, he hopes to share the wonder and bring us together in unity and understanding

“IN Meah Shearim, if you walk around with a camera, the locals are so used to it that they’re immune. There’s a history of many decades of photographers roaming around there, with so many photo books on life in Yerushalayim, that the concept has grown on the community. Yerushalmi men have told me that their grandfathers are in the pictures in some of the well-known books. But we don’t have many photo books on chassidim in Brooklyn. I saw a potential space.”

Photojournalist Abe Kugielsky says his early education in a chassidish elementary school has helped him realize his passion for photo-documenting chassidish life in New York. “I understand chassidish nuances, and I have the language, so I can connect.”

And he does connect. Many of his accounts of the pictures he’s taken finish with, “and then we had a conversation for an hour,” or even, “I go in to visit this guy whenever I’m passing by, just to schmooze.”

As a child, Abe loved browsing through photo books, and Russian-German Jewish photographer Roman Vishniac’s piece de resistance, A Vanished World, spoke deeply to him. The family business of antique Judaica stimulated a passion for history, and Vishniac’s iconic pictures of Jewish life in the once-bustling shtetlach gave Kugielsky a sense of the power of street photography to bridge generations. While learning in the Mir in Yerushalayim, he met up with photographer Eli Greenwald (ak.a. Boruch Yaari), picking up skills and techniques to bring his hobby into clearer focus.

Photography is more widespread than ever today, thanks to phones with camera function, but Abe observed that most people only take pictures of their families, and that no one is documenting the community. He recognized the potential opportunity and in 2011, excited but afraid of rejection, he dipped his toes into the beckoning waters.

At first, Abe kept to the shadows, afraid his subjects would not appreciate being photographed. At the core of this hesitation, Abe believes, is a lack of trust. “When was the last time chassidim were in the media for positive reasons? Exposure of the community through photography almost always casts them in a negative light, going back generations. So why should they trust an outsider with a camera?”

Careful to keep a low profile, Abe would stay in the shadows looking for moments to capture from a safe distance. With time he accumulated a large collection, and after three years and 30,000 photos, he started to share the pictures online. The level of interest took him by surprise and pushed him deeper into this sideline.

Abe posted one picture a day, always with a positive comment, telling the positive micro stories of life in the chassidish sector. He’d comment on the emotion, the humanistic angle. “My story is how much we have in common as Jews, and how much we have in common as human beings.”

Initially, though, he kept himself anonymous. While his vibrant pictures of chassidish life were posted and reposted, no one knew who was behind the camera. “I’d wait a couple months to post my pictures because otherwise I’d be recognized on the CCTV system.”

Moving into the Open

Abe’s rav’s position is that it’s permissible to photograph people as long as they’re in public spaces, and the American legal position is very similar. But wanting to get candid shots, in true spy-novel fashion, Abe used a hidden camera to take photos in shuls and at tishen. At first Abe declines to tell us where he kept his camera. “I could be just two inches away from someone, and he didn’t know what I was doing. It was built into a book that looked like a siddur. But I won’t say more.”

Abe captured the Shacharis scene inside Boro Park’s homey shtiblach, the warm l’chayims at tishen, the Tashlich gatherings, and the special glow of Chol Hamoed in chassidish circles.

He admits that he encountered pushback and even threats at the beginning. “They didn’t know who I was,” is his take. “But with time, as my audience grew, and as my chassidic audience learned to appreciate that I aim to showcase the beauty of chassidic life and of Judaism, their attitude changed. Four years ago, I came out of hiding and did an interview with one of the Yiddish magazines. Now people invite me into events and stop me in the streets of Williamsburg for selfies.”

Abe runs an antique Judaica business, which is how he came by his interest in history and tradition. “When I close my gallery for half a day, get into my car with the camera and drive to Williamsburg, it’s therapeutic for me. I’m in another space, in my own artistic world.”

He admits that a project of this nature necessitates a lot of juggling; while his wife is his number one fan and supports all he does, inevitably, there are conflicts between his interests and family life, especially at special times like Purim, Pesach, and Chanukah, when the chassidic courts beckon with the buzz of heightened action.

A Place in His Heart

Although Abe’s collection also features pictures shot in Kiryas Joel, New Square, Monsey, and Boro Park, it’s clear that Williamsburg has a special place in his collection — and his heart.

“It’s my favorite place!” he affirms. “Very dense and congested, with a lot going on, so that I don’t have to struggle to find a ‘moment.’ They’re all around.”

He knows there are chassidim in Lakewood as well, but he says the lifestyle there doesn’t lend itself much to street photography. “There’s not much of an outdoor life, because people live so far apart and use their cars.”

What about Crown Heights, we press him. He says he knows that of course it features a sizeable chassidish community, but he focuses on the more iconic look his viewers want to see.

Beyond the gratification of sharing of his art, Abe receives obvious satisfaction from the audience feedback he consistently receives. One lady in Williamsburg told him that the evocative photography and the stories it tells have made her realize the beauty of her own culture again. Unaffiliated Jews have shared that they’ve benefited from peeking into the culture of chassidim, not only gaining understanding but enriching their own lives.

A message from a follower in Brazil let Abe know that he was reticent to display his Jewishness and wear a kippah and tzitzis regularly “because I see these guys in New York doing it, and I feel inspired to do the same here.”

Another wrote, “I am not religious at all. I used to be anti-religious, but now, after following you, I am growing in respect and love for Hasidic Jews.”

As for non-Jewish people, dozens of individuals have messaged Abe on social media in the “OMG I love Judaism! How can I convert? I love Hassidic Jews, I want to be one” vein.

The feedback isn’t all rosy of course; the hate reaches him too. Yes, a lot of people out there think Hitler should have finished us off. And they’ve become bolder in expressing that hate since October 7. Still, he says the overwhelming majority of the feedback is positive.

So are we more popular than we think we are? Abe thinks so, although the general media won’t project those positive feelings.

But outsiders’ perspectives aside, perhaps the main thing is that, like Abe, we look at each other through a positive lens, appreciating all that we share, and letting the shining moments highlight what we admire and respect in a truly unique community.

Getting His Feet Wet

I

was driving down a street in Boro Park with some friends after a heavy rain, when we saw this guy in the middle of the road, soaked to his socks, holding an upside-down shovel. We opened a window to ask him what was going on — my guess was that he had dropped his phone or was looking for something. He said “Ich hob gezen an alter Yid, er ken nisht valken — I saw an elderly man trying to cross the street but he couldn’t walk because of the puddle, so I figured I’d unblock the drain.”

He was trying to release a water blockage so that people could walk. What a great moment. This one went viral, deservedly.

From a Fading Era

T

here’s a fish store in Williamsburg with no signs, no window. You’d never know it’s a store. The owner has been selling fish for 50 years, and nothing’s been replaced or changed in all that time. No cash register, only pen and paper. No computer, only an old phone with a wire. I get excited when I step in there, because this is what’s left of history. It’s like the last corner left of old Brooklyn.

The store’s not open every day, only l’kavod Shabbos, on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Erev Yom Tov. When I asked the owner for a picture, he was very hesitant, but once we started schmoozing, he warmed to the idea and agreed. By now we’ve become friendly, and I visit him whenever I walk down that street.

There was a similarly styled old grocery store on Lee Avenue 12 years ago. The owner was of the old generation, and there was nothing modern in sight. But she passed away, and everything has been turned over and refurbished. It’s gone. People still appreciate these scenes… although I don’t know if they still flock to shop in these stores.

Beware of Dogs

I love this picture: the two bochurim looking at the dog, with the Williamsburg vibe so clear in the store name and in the New York hipster walking by.

When I posted this, I learned from my audience that the fear of dogs is rooted in Holocaust-related trauma. That was something I didn’t know….

Open to Friendship

This is a picture from 12 years ago. I was driving through the rain when I caught sight of these two bochurim schmoozing at the two doors. With just a second to capture it, I pulled out my camera and snapped.

Posed pictures just aren’t the same. I try to get my picture without the subject knowing, not because he won’t let me snap if he knows, but because you lose the moment; the person’s demeanor changes. I’ll walk around a car, capture the moment, and then converse afterward.

Tish Tales

W

hile I have plenty of regular tish photographs, with hundreds or thousands of men standing on the parentches around the Rebbe’s table, and the awe-inspiring presence of the Rebbe at the head, I love the angle of this one, taken at the Lelover Rebbe’s Lag B’Omer tish. You don’t see the Rebbe, but you do see everyone looking toward his chair with such seriousness, and that captures the aura and the respect.

L’kavod Shabbos Kodesh

IT was Erev Shabbos, just an hour before Shabbos was coming in, that magical time when the world is about to stop for us all. I was already on my way out of the neighborhood, when there he was — an elderly Yid in his flowered silk beketshe, with his Shabbos shopping and his hadasim carefully held aloft in his right hand. The whole moment emphasized the beautiful significance of the avodah of preparing for Shabbos.

Kid Friendly

Kids love being photographed, by the way. When they see a photographer, they think they’re going to be featured in the Yiddish children’s publications like A Blik or Der Voch, and they usually won’t leave me alone unless I snap pictures of them. From my perspective, though, I prefer authentic moments, where the subject is totally natural, and unaware he’s being captured. So I don’t interact that much with kids.

Response in Kind

Icaptured this beautiful picture of the Karlsburger Rebbe walking down the street one snowy day. After I got a nice shot, I engaged the Rebbe in conversation and asked if it would be okay for me to photograph him in the beis medrash while he was learning. The Rebbe said no, he preferred I didn’t. He went to the building of the beis medrash, but then came back to the doorway and posed for me there. The Rebbe checked that I was happy with my picture, and then he went in to learn, closing the door behind him.

Hats Off

I

was driving in Williamsburg when I saw a chassidish hat sitting on top of the trash outside. I wanted a shot from a different angle. After taking a picture from inside the car, I got out, but by that time a passerby had already picked up the hat and was calling the guy whose name was inside to do hashavas aveidah. Then he gently placed it on the spokes of a nearby fence, so the chassid could come pick it up. This set tells the story of someone acting quickly to help out.

Capture the Cellar

SOmany stores used to have these outdoor entries to the cellar when I was a kid, but now they’re disappearing. I was driving down 13th Avenue when I saw this guy coming out to the sidewalk. It sparked my interest, I had to wait a long time to capture it. Whenever I passed by, I’d sit outside for a few minutes and wait and hope. Then after three years, here he was clambering out with his vases. Actually, it happened again as I drove by soon afterward, and I got my shot twice within a month!

All on Board

Getting ready for Succos in Williamsburg can mean getting the succah boards out from a 150-year-old cellar. There’s a lot of deep nostalgia here, because you don’t see cellars like this anymore.

Nostalgia in Monsey

Iseek out nostalgic scenes like this, because the traditional scenes attract me. A lot of my audience connects to them too. Let’s wait and see — the next generation may enjoy the more modern scenes I capture, like a chassidish guy working at his computer or enjoying a ropes course, but today people want to look back at their own childhood.

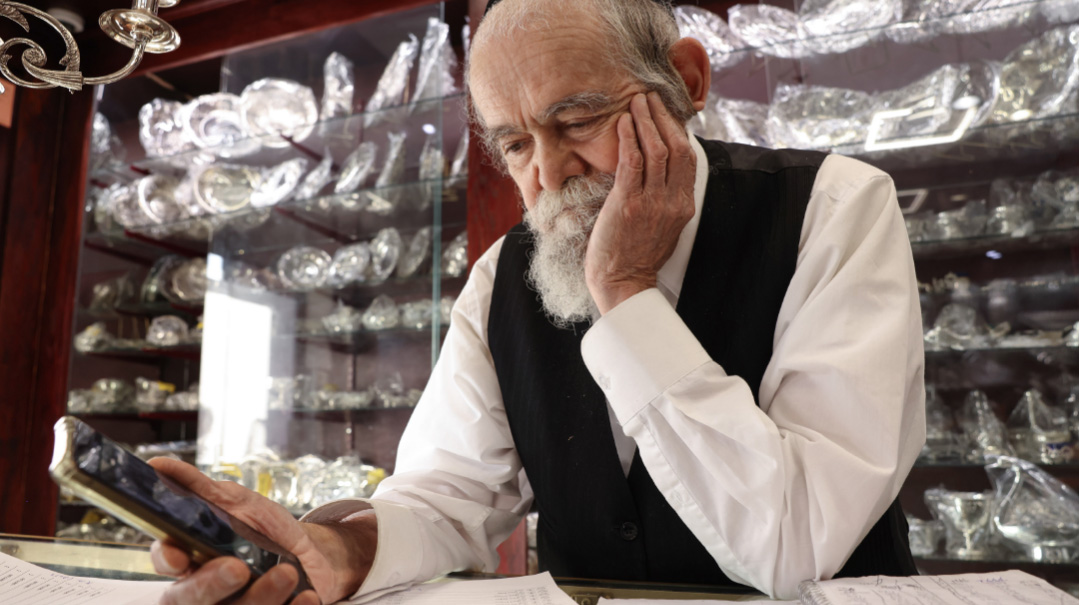

Close to Home

IT

was Lag B’Omer, and I had a little gap before it was time to go to the fires in Boro Park. I walked into a silver store, and because it was a private business, I asked the owner’s permission to photograph him.

“Farvuss darf ich dus — What do I need it for?” he said, trying to deter me.

I tried to explain the value of documenting and archiving life in the community, for the future, and I handed him my phone, on which I’d downloaded black-and-white street photos taken in Williamsburg in 1964, which are archived in the Brooklyn Public Library.

The store owner appreciated the old pictures and started to scroll through them. Then suddenly, he froze, and his expression intensified. I could see he had gone into another world.

“What is it?” I asked him

“This is mine wife!”

He’d found a picture he’d never seen before of his wife, pushing a carriage along the street in Williamsburg in 1964, with her father.

My point about street photography was made.

Actually, I’d had a similar experience. I had just started to grow closer to the memory of my grandfather, Rabbi Moshe Yemin, and learn from his sefer. I was searching for antiques on eBay, and I suddenly found a picture of him for sale dated 1985, taken by a street photographer in Yerushalayim.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1008)

Oops! We could not locate your form.