Signed, Sealed, and Saved

| April 16, 2024Back in the day, a letter was something to be treasured, a tangible medium of interest, hope, and love

As told to Riki Goldstein

Project Coordinator:Rachel Bachrach

Nowadays, when our communication often takes the form of emoji-splattered text messages, it’s hard for us to relate to the import of what we sometimes derisively call snail mail. But back in the day, a letter was something to be treasured, a tangible medium of interest, hope, and love.

A Final Missive

From: My grandfather, Rabbi Aharon Berek, Vilna

To: Rebbetzin Basya Bender, New York

Date: 1941

I was born in Shanghai, where my father had joined the Mirrer yeshivah in their escape from Europe. In 1946, we arrived in America. About 50 years later, Rabbi Yaakov Bender phoned me. His mother, Rebbetzin Basya Bender, had been a friend of my mother’s, and had been very close to the Berek family in Vilna. Now he’d found a letter among her papers. The letter was from my mother’s father, Rav Aharon Berek of Vilna, who was Rav Chaim Ozer’s private secretary and the secretary and bookkeeper of the Vaad Hayeshivos, and was written to Rebbetzin Bender. Dated September 1941, it read as follows:

“My daughter Rashel has left here with her husband, who will be a very fine talmid chacham. I do not know where they are, but maybe, from America, you can find out.”

My parents got married in Vilna in 1940, against the backdrop of crisis and uncertainty. But the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact between Germany and Russia had left Vilna temporarily safe, and Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzensky had invited all the yeshivahs to take refuge in the town. The Mirrer yeshivah, which had also relocated to Vilna, was planning their escape. Although my father was a talmid of Kletzk, not Mir, he wanted to go along with the Mirrer group.

My mother, though, didn’t want to leave her family to travel across the world. So my father went in to the Brisker Rav and told him that his wife didn’t want to escape. The Rav sent his daughter, Lifsha (later Rebbetzin Feinstein) to call my mother in. “Go,” he said. “You will be saved.”

My mother didn’t dream that the Rav meant she would be the only one of her family to survive. But with his instruction, she said goodbye to her parents, and my parents joined the Mir group, together with some 11 other Kletzker bochurim, some talmidim of Lublin, and some Chabad bochurim who joined the Mirrers on their miraculous journey. Soon after they left, the Nazis came to Lithuania and wiped out 90 percent of its Jews. No one remained from my mother’s family, nor my father’s.

Heartbreakingly, my grandparents didn’t know that my parents had reached safety, while likewise my parents didn’t know how their families were faring in Lithuania. In fact, when I was born in Shanghai, my mother did not give me her mother’s name, because she did not know that her mother had been killed.

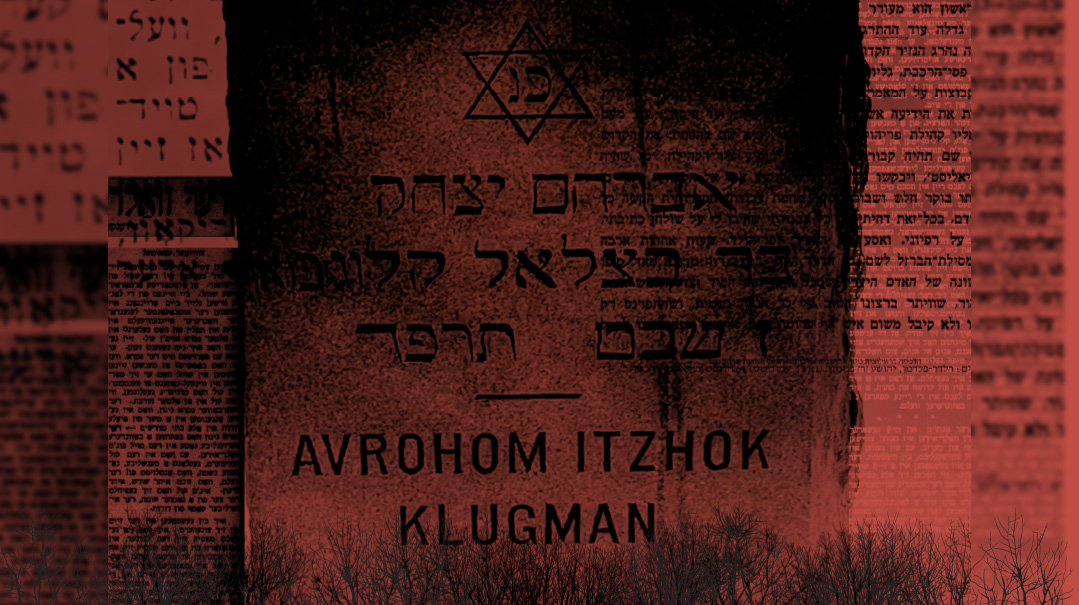

After the war, Rabbi Pinchas Teitz told us he saw the grave of my grandfather, Rabbi Berek, in Vilna. He died very young, but just before the Germans liquidated the remaining Yidden, and so he has a proper grave. My grandmother, aunts and uncles were all killed in the Vilna ghetto — and only later, when my mother was in her eighties, did an eyewitness tell her that her younger brother Avrohom died of starvation. This person didn’t realize what pain he had caused her; for a while she couldn’t put food into her mouth.

When I got the letter from Rabbi Bender, I read it to my mother. She found it deeply painful but very precious. My mother was not even aware that her grandfather had a second name, Mordechai, until I read her the letter, where her father signs Aharon ben Nochum Mordechai HaKohein. It brought back a flood of memories, and the bittersweet touch of her father’s love and concern for her, across a painful chasm of separation and suffering.

Rebbetzin David is the wife of Rabbi Hillel David of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah, and daughter of Rav Mendel Krawiec ztz”l, the rosh yeshivah of RJJ. She teaches classes on sefer Tehillim and is also the English principal of Yeshiva Tiferes Elimelech.

Express Consolation

From: Rabbi Edwin Katzenstein, Washington Heights

To: Baila Josephs

Date: 2002

“I

’m not hearing a heartbeat.”

The doctor’s voice was softer, more measured than his usual breezy clip. “I want to show you what I’m seeing, because we need to discuss how to proceed.”

I was 23 years old, moving along the “seminary, teaching job, engaged, married, expecting one, then another, then another” track. With two healthy toddlers at home, this appointment was meant to confirm another bundle of sunshine on its way. “No heartbeat” did not appear on my mental script.

But I kept my composure as the doctor pointed to his screen. “You’re in your second trimester, farther along than you may have realized,” he said. “We’ll probably need a more complex procedure to bring this pregnancy to a safe end.”

He then explained the logistics of the procedure he had in mind. I tried to process the details, but they felt too surreal to actually be applicable to me.

Of course, I knew that not all pregnancies result in a healthy baby, that when you open yourself to the hope of new life you also must be prepared for it to end the other way. But until then, it had just been textbook knowledge.

My eyes dry but heart pounding, I made a show of listening, thanked the doctor, told him I’d be in touch. Then I mechanically continued on to work.

When the boss left the room, I closed the door, dialed my husband, and finally the tears came.

That night I called my parents. “I have a problem and I might need your help,” I said directly.

My father, who volunteers for Hatzalah, told me to wait a few hours so he could explore the options. Soon enough, he called back with a recommendation. “This doctor is considered the best and most experienced for your case,” he said. “He has a private office on Park Avenue in Manhattan, and he’ll want you to do some additional scans to confirm the details. Here’s the number of his secretary — call tomorrow morning and she’ll tell you what to do.”

It was comforting to have someone else dictate the instructions. All we had to do was follow; show up here, wait there, do this scan, speak to this posek, consult this doctor… But then there was an unexpected twist.

“You’re Orthodox Jews,” the doctor told us after he reviewed the scans in his meticulously decorated office. “So I want you to know in advance that the fetus is at a more advanced stage of development, and according to Jewish law, it will require burial. That’s something you’ll have to arrange.”

My husband nodded. On our way back to the car, though, we looked at one another in panic. Kevurah? That was for adults, not young couples playing house. What were we supposed to do?

My parents came through again, contacting the KAJ Chevra Kadisha in Washington Heights, not far from the hospital. “They’ll take care of everything,” my father reassured me. “You just take care of yourself.”

The procedure was painful in many ways. The aftermath was even harder. All around me were babies or mothers expecting babies. I knew my emotions weren’t so logical — I had two healthy children, no fertility concerns for the future, and so much to be grateful for. But the loss was still a loss.

A week later, my father called. “I’m mailing you a letter I received,” he said. “Keep an eye out for it over the next few days.”

When it came, I opened it curiously. The letter was typed on formal, cream-colored paper, and the name of the sender was unfamiliar, a Rabbi Edwin Katzenstein. He was, I later learned, the legendary head of the KAJ Chevra Kadisha; this was just one of the many vital posts he filled.

His note was short but I read it and reread it, then folded the paper tight and put it away to reread when the questions and pain returned.

“Our brethren in Eretz Yisrael are going through a very difficult time, and we are in great need for HaKadosh Baruch Hu to have compassion and mercy. The very brief sojourn of a neshamah in our world has a reason, and I am sure that it now joins the many neshamos tehoros appealing to HaKadosh Baruch Hu to be meracheim on Klal Yisrael.”

It’s been decades since that experience, and 15 years since Rabbi Katzenstein was summoned Upstairs to receive his Divine reward. But in an envelope deep inside a drawer, I still keep his note — the note he sent to a woman he’d never met, whose mailing address he didn’t even have, but whose need for consolation he managed to intuit.

Baila Josephs is a mother, grandmother, and writer living in Brooklyn.

Saved on Seder Night

From: My father, Reb Binyomin Zev Lowy a”h, and his friends; Nitra, Slovakia

To: Rav Michoel Ber Weissmandl ztz”l and the Stropkover Rebbe, ztz”l

Date: Erev Pesach, 1945

T

his is a letter written in lemon juice; you can see the Yiddish script appearing in a funny brown color. Lemon juice is a homemade invisible ink — the writing cannot be seen until the paper is heated, when it turns brown. My father and his friends used it to send messages from one hideout to another in Nazi-occupied Slovakia. My father was a talmid in the Nitra yeshivah when the Holocaust began. When the Nazis deported the local Jews to Auschwitz in the last months of 1944, my father evaded deportation by hiding in a bunker together with a group of Nitra talmidim.

Before the yeshivah dispersed, the maggid shiur Rav Michoel Ber had given his talmidim two ideas to clandestinely communicate with him if necessary. One was to place a classified ad in the local newspaper, using a certain codeword. The other was to write a fake business letter in Slovakian on one side of the paper, signed off “Ne’elam” (“disappeared,” in Hebrew), with the real message in lemon juice on the other. Working with members of the underground, Reb Michoel Ber could then send the boys money, which they needed to keep bribing the gentiles who were hiding them; seforim; and other vital items.

In March 1945, the Russians were chasing the Germans out of Slovakia. Knowing that the Russian soldiers were violent, drunk, and corrupt, the bochurim wanted their rebbi to guide them in what to expect and how to deal with the Russians. On Erev Pesach, they wrote this letter asking for advice. You can see ten full names, with their mothers’ names, too, because they are also asking him to be “mazkir” their names to the Stropkover Rebbe, who was hiding in the same bunker as Reb Michoel Ber.

Baruch Hashem, for this group, the story had a happy ending. Together with his friends, my father remained in his bunker until the second night of Pesach, when the Russians liberated Nitra. When they left their hiding place, they met other friends who had just come out of their own bunker. “A Gut Yom Tov, a freilechen Pesach,” my father’s group said, but the other boys disagreed.

“It was a leap year, it’s Purim night now,” they claimed. Reb Michoel Ber had sent his talmidim a handwritten calendar so they could keep track of the luach, but it had not reached that group of bochurim. For some reason, they had mistakenly calculated that the year was a leap year. (For years the friends would refer to this argument each Pesach as they walked home from shul in Williamsburg.)

My father’s parents were killed by the Nazis, and his only surviving brother moved to Eretz Yisrael. He joined the yeshivah when they relocated to the United States, married in the yeshivah dining room, and after some years in Williamsburg, moved the family to join the Nitra yeshivah enclave in Mount Kisco, New York.

My father, who recently passed away, was a talmid chacham who retained the erlichkeit he’d absorbed in Nitra yeshivah all his years. I’m keeping this letter so my children and grandchildren can understand something of the dangerous times their Zeide and so many other Yidden went through, and the kind of strength they had to draw on to become who they were, despite the traumatic losses.

Lesson Spanning Generations

From: My seventh-grade rebbi and English teacher

To: My mother

Date: December 11, 1959

S

ome therapists choose to decorate the walls of their offices with only their diplomas, license, and an occasional nondescript landscape, perhaps in order to minimize transparency. By contrast, the walls of my office are so filled with artwork, photos and memorabilia that one might call them cluttered or even cozy, more like a museum than a therapist’s office. Each item holds special meaning for me.

On the middle of one wall, between a photo taken of me with Harav Chaim Kanievsky ztz”l and one of the Chofetz Chaim ztz”l, hangs a simple black frame encasing a letter dated December 11, 1959. The letter was written on official yeshivah stationery and was addressed to my mother a”h. It was signed by both my seventh grade rebbi and English studies teacher.

The letter reads as follows:

Dear Mrs. Wikler,

We find that Meir has been boisterous and rude in both his English and Hebrew classes. Although we have called his attention to this matter, we find he hasn’t corrected his behavior. Because Meir’s father hadn’t been feeling too well, we have hesitated to request that you come to see us. Your cooperation will be appreciated.

Respectfully yours,

I have absolutely no recollection of my parents receiving this letter. In fact, if my older brother had not found it while going through some old papers from our childhood home, I would not have even known about its existence.

Today, it hangs prominently in my office, where it serves a dual function.

First, it reminds me of the loving, wise judgment my parents displayed. Had they shared the letter with me, it certainly would have negatively impacted my relationships with my teachers and my learning in general.

Perhaps more importantly, it’s available for me to share with parents who consult me about their oppositional and challenging children. Sometimes, I meet parents who are enduring living nightmares because of their children’s behavioral issues. They often sigh hopelessly and lament, “Whatever will become of that child?” Whenever I hear that, I reach up, take this letter down from the wall, and hand it to them to read.

Recently, I met with a mother whose son is struggling. He is disrespectful, disobedient, and lackadaisical about his schoolwork. He constantly makes demands for things which his parents do not want him to have. In recounting her tale of woe, the mother was practically brought to tears.

I directed her to the letter, and after reading it, she smiled and said, “That makes me feel better.”

The message was clear. If I started out where I did and ended up pretty much okay, then perhaps there really is hope for her son.

Dr. Meir Wikler, is an author, psychotherapist, and family counselor in full-time private practice with offices in Brooklyn, NY, and Lakewood, NJ. He is also a public speaker whose lectures and shiurim are carried on TorahAnytime.com.

A World That Was

From: My Father, Mr. Sholem Erlanger and His Brother Heiri (Elchonon Tzvi) Erlanger

To: My Grandparents, Yaakov and Roseli Erlanger

Date: 1935–1939

MY

great-grandfather was among the founders of the Lucerne kehillah, a small Swiss community absolutely dedicated to Yiddishkeit. But while community life was very wholesome and frum, Lucerne in the pre-war years did not offer opportunities for boys to gain a high-caliber Torah education. My grandfather, who wanted more for his boys, hired a “haus-lehrer,” a private rebbi, to teach them. This melamed he found was a Dr. Michoel Posen from Frankfurt, a genius who had no less than seven doctoral degrees.

Once my father and his brothers grew up, Rabbi Posen convinced my grandfather that they needed to learn in yeshivah, a novelty in Switzerland at the time. He suggested the yeshivah led by his brother, Rabbi Shimon Yisroel Posen, the Shoproner Ruv, Av Beis Din in Shopron, Hungary. (While the Posens were scions of a German rabbinic family, Rav Shimon Yisroel became a distinguished chassidish rav).

While he had already started training in a nearby farm and was more interested in traveling to Palestine to help the agricultural settlement, my father indeed traveled from Switzerland to learn in Shopron, where he remained for three years, becoming very close to the Ruv and even serving as his hausbochur. His letters to his parents from that time period are detailed and fascinating; as an “outsider” from a different world, he records every impression. In one letter he records traveling with the Shoproner Ruv to spend Shabbos with his great rebbe, the Minchas Elazar in Munkacs.

The first weekday minyan for Shacharis was at 5:30, and minyanim continued steadily until 10 a.m. On Shabbos, the tish was held in a large succah-like structure, roughly 10 meters by 20 meters. The Rebbe came in at 11 p.m., with two gabbaim. He sits on an ornate chair. Five hundred people were crowded into the room, and where there is no space, they stand on the table.

The tish began with Shalom Aleichem… the Rebbe made Kiddush, and a large shissel of fish was brought. The Rebbe ate two pieces, and started to give fish to the rabbanim present. Suddenly, the crowd pressed forward, climbing on tables and chairs. It looked like a war as they pushed and fought to get the shirayim. Like a beehive swarming with bees. As I have written to you about this, whatever the Rebbe eats lesheim Shamayim has kedushah, and here, one fights to get a little of it. After zemiros… bentshing was at 2 a.m.

Davening in the big shul began at 9 a.m. I had a seat near the chazzan, and from “Shochein Ad,” the Rebbe himself leads the davening. After Shacharis, at 10:30, the Rebbe gave a “knakedicke derashah” for two hours. I will write to you just one vort that he said. “Bar Kamtza [who caused the destruction of the Beis Hamikdash] stands for the Beitar movement, the Revisionist (Zionists), the Communists, the Mizrachisten, the Zionim, and the Agudisten!”

After three years in Shopron, the Ruv suggested my father move on to the yeshivah in Galanta. But after only six months in Galanta, my father’s brother, Uncle Heiri, intervened. My father had turned into a chassidishe bochur complete with a beard and peyos, and Uncle Heiri wanted him to leave the chassidish Hungarian environment and come learn in the litvishe world.

Heiri himself was in Baranowitz, and of course he was corresponding with my grandparents too. In his letters, he records word for word his brief conversation with Rav Elchonon Wasserman. What’s interesting is that after they had exchanged a few sentences, other bochurim told him that no student had ever conversed so long with Rav Elchonon — “perhaps only the foreign boys.”

Now I will write something you want to hear from me,” Heiri writes to his parents, “this is how many zlotys I have spent… on my room… breakfast… smoking… yeshivah… and laundry. I still need galoshes, a blanket, a shtender, tzitzis, gloves, a wool coat, a suit, a fountain pen, a German-Polish dictionary, a Chumash, a Gemara, and a mussar sefer.

His letters also offer a picture of the primitive facilities, such as his account of having an unlicensed dental technician fix a bridge that fell off his teeth for 16 zlotys.

The waiting room and dental practice are all in one room. The patient sits on a high-backed wooden chair, with a dirty towel behind his head. The drill is a relic from the times of Terach — the technician operates it by pressing a pedal. On the window sill, I can see some plaster, also bread and leftover chicken bones and a metal figurine. He has no one to keep the place clean. When his fingers crawl into your mouth, it is gross…. There is a metal wire around the chair leg, for patients’ spittle… but he’s a good worker, does it cheaply, so that you shouldn’t inform on him to the authorities for practicing illegally.

Heiri also writes of non-Jewish thugs, some kind of mafia, beating up rich Jews in Baranowitz, right near his lodgings. Since Baranowitz catered to younger boys, while Heiri was already 20, he didn’t learn there very long but moved on to the Mir. At that stage, he tried to convince my father to join him. After asking permission from the Shoproner Ruv, my father went to join Heiri in the Mir. They heard shmuessen from Rav Yerucham Levovitz and soaked everything in, both becoming close friends of Rav Shloime Wolbe.

From the Mir, on February 18, 1936, Heiri records for his parents the Mashgiach’s shmuess when the Polish government threatened to ban shechitah. On July 28, 1938, Heiri attended the wedding of Rav Mordechai Schwab, in Mulch, Poland, and in his letter home he describes every detail of the chuppah and reception.

My father’s experiences in Poland came to an end with World War II. Together with Rav Shlome Wolbe, he made his way to Stockholm, Sweden, in 1939, where they hoped to wait out the war and soon return to the Mir. However, when it became clear that the situation wouldn’t be resolved quickly, Rav Wolbe advised my father and his brother to make their way back to Switzerland. They journeyed on the last train to travel through Poland and Germany before the war broke out. In Berlin, they checked into a hotel overnight. Failure to close the window blinds brought Gestapo agents to their room, but fortunately, at that stage, Swiss passports still offered adequate protection for Jews, and the agents sufficed with throwing them out onto the street.

Ultimately, my father reached home safely, and with that the yeshivah period of his life ended, though the memories are captured and cherished in pages and pages of flowing German script mailed to his parents.

A fourth-generation Swiss Jew, Mr. Reuven Erlanger maintains a treasure trove of information, documents and pictures of the Lucerne Jewish community, Lucerne Yeshiva, and Lucerne Seminary. He is retired and lives in Manchester, U.K.

When No Is Yes

From: The Institute of Chartered Secretaries

To: My father, Mr. Nathan (Nosson) Halle

Date: 1953

MY

father was 16 years old when he left Germany on a train full of SS men.

When he arrived in England in the winter of 1938/39, he spoke no English at all. He was directed to a refugee hostel for Jewish boys in Leeds, where he stayed until he discovered that none of the staff seemed to know anything about the approaching Yom Tov of Shavuos. Somehow, he made his way to London, where he found a larger, frum, supportive community in Golders Green. I have the postcards written by his parents in Yiddish in which they inquire after his health and ask with increasing desperation for my father and his sister to assist in getting them out of Europe. In 1941, when Germany invaded Lithuania, the postcards stopped coming, and my father and his sister never heard from his parents again.

My father’s sister Suzie had left Germany before him, bringing his violin along, and was employed as a maid in the home of a kind family. That was all the family my father had, until he eventually married my mother, Ruth Guttmann a”h.

While working, he had begun studying to become a chartered secretary, a UK corporate secretarial position ensuring statutory compliance. He had been studying for some time for the required examinations, when he discovered that they were scheduled for Shavuos.

My father wrote to the examination board asking to take the exam on another date, but his request was refused. The Board of Deputies of British Jews also attempted to influence the board, but they were unsuccessful.

The reply from the Institute of Chartered Secretaries was very polite, very British, but very clearly, a no. A polite version of, “If you can’t take the exam on the day we set it, tough, you can’t join this profession.”

Of course, for Daddy, of the strong background and rabbinic lineage, there was no question at all. Shavuos was utterly nonnegotiable.

Once he’d absorbed the disappointment, he explored other options and decided to study accounting, which was a better career, although it took him years to qualify. And so this letter led him up another career path, thankfully, both stable and successful for Daddy.

When we cleared out his papers after his passing in 2001, I kept this letter. It’s a sign of how the no’s can be catalysts for the yeses in our lives… and a sign of the love for Yiddishkeit and uncompromising stance on halachah that he passed on with such love.

Debbie Guttentag is a published author of novels for teens and young adults and teaches drama in the chareidi community. She lives in Manchester, UK.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1008)

Oops! We could not locate your form.