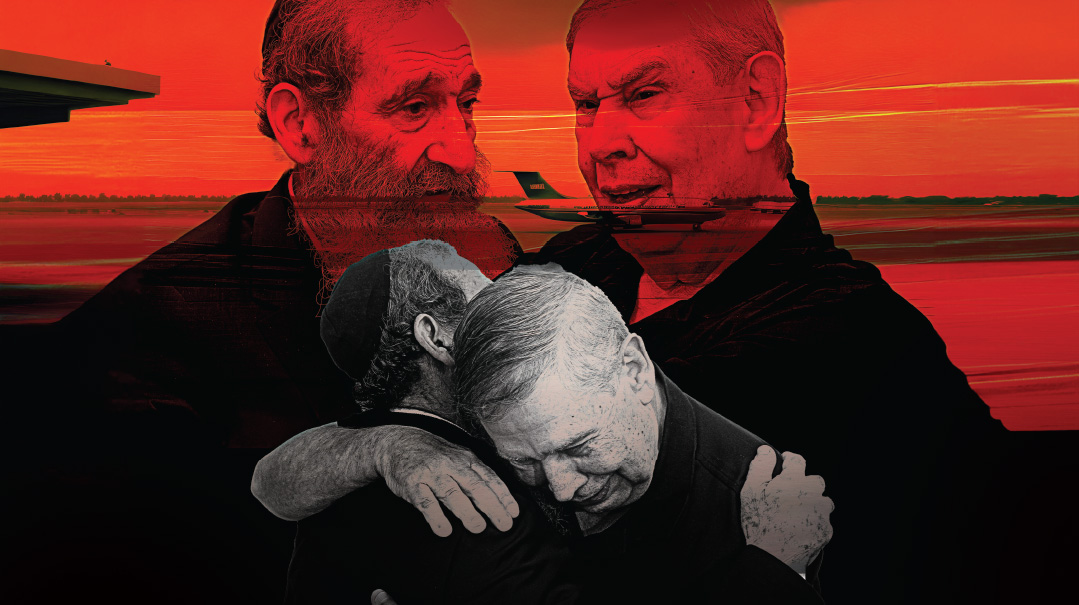

War of Atonement on Yom Kippur

50 years later: Shedding new light on the politics and players of a war whose stakes were nothing short of survival

Book excerpts by Uri Kaufman

Photos: Government Press Office

ON Yom Kippur afternoon in 1973, Uri Kaufman, today a lawyer, writer, and award-winning real estate developer from Lawrence, New York, was a nine-year-old boy running around in the Connecticut shul where his father was the rav. Outside in the lobby, far from where his father could see, he noticed a group of men huddled around a transistor radio, as another group of men screamed at them for bringing a radio into shul on Yom Kippur.

“It was the first time I ever saw anyone bring a radio into a shul on Shabbos or Yom Tov,” says Kaufman, whose new book, Eighteen Days in October, tells the heart-stopping tale of the Yom Kippur War from the perspective of half a century. “A week later, during Succos, my father broke down and cried as he stood before the kehillah reading the tefillah for Israeli soldiers. It was the first time I ever saw him cry.”

Exactly 50 years ago, on October 6, Yom Kippur of 1973, the armies of Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack against the State of Israel, and the ensuing 18 days of bitter fighting would become known as the Yom Kippur War. The cause of the onslaught was rooted in the lingering wounds and shame inflicted on the Arabs by Israel in the 1967 Six Day War, shadowed by the refusal of Arab countries to accept the presence of a Jewish state in the Middle East.

The war began badly for Israel, as thousands of reservists were pulled out of shul in their talleisim and headed for the front. The fighting was some of the fiercest in the post-WW II era; ultimately, over 2,600 Israeli soldiers would be killed. The Egyptians crossed the Suez Canal and advanced into the Sinai Peninsula, while the Syrians penetrated deep into the Golan Heights and headed for the Kinneret. Worse still was a devastating loss of IDF equipment.

But the Israelis soon recovered and made a startling comeback. They pushed the Syrians back beyond their original ceasefire line and advanced within artillery range of Damascus suburbs, while in the south, they crossed the Suez Canal and managed to surround the Egyptian Third Army, less than 60 miles from Cairo.

“The Yom Kippur War has always fascinated me,” Kaufman says. “It’s a story that exceeds anything a novelist could have ever contrived. After nearly being routed, the IDF clawed its way back to threaten Cairo and Damascus. I started researching it over 20 years ago, reviewing thousands of pages of old records and documents, traveling to the Sinai Peninsula, visiting battlefields, and talking to the people who experienced it first-hand — although my wife Esther would probably have preferred that I join a daf yomi shiur instead.”

Kaufman, whose real estate development firm, The Harmony Group, specializes in transforming historic buildings into thriving properties, had a lot of help in researching this other aspect of history closest to his heart.

“A team of researchers around the world joined the project, including researchers from Ukraine and Germany, deciphering foreign records and interviewing foreign witnesses, as Russia was Egypt’s main patron,” he says. “I’m certain the team uncovered material that was reviewed for the first time. As for me, I went through thousands of pages of government transcripts, reviewing them as they slowly became declassified over the years. The best material has only been released in the last 10 to 15 years, allowing us to listen in on world leaders as they debated life-or-death issues and made decisions that still cast a shadow over the region.

“And of course, I spoke to many veterans myself. Perhaps the most extraordinary of them was Maozia Segal, a triple-amputee who miraculously survived his wounds and became a true source of inspiration, going on to a successful career and raising a family. He was honored this past year on Israel’s Independence Day with one of his nation’s highest honors. Of course, not everyone was so lucky. Others I met carried traumas that were still apparent decades later.”

There were various technical reasons for Israel not being prepared for the attack on both the northern and southern fronts that fateful Yom Kippur morning, but perhaps mostly, it had to do with a pervasive mindset.

“Pretty much total complacency,” says Kaufman. “Those in power didn’t believe the Arabs would dare to attack, and thought that if they did, the meager IDF forces along the front would be enough to beat them back. According to their plan, the reservists were only to be used for the counterattack, not for the defense.”

Israel had one rolling bridge and two pontoon bridges. Would that be enough to secure the troops who’d daringly crossed the Canal?

Did they feel Israel was invincible? Did anyone acknowledge the great miracle of the 1967 war just six years earlier, or was it a feeling of “kochi v’otzem yadi”?

“There were many in Israel who saw evidence of yad Hashem. For example, the secular year 1948, the year the State of Israel was founded, corresponds to the Jewish calendar year of 5708. The 5,708th pasuk of the Torah reads, ‘And the L-rd shall bring you to the land that your fathers inherited, and you shall inherit it and the L-rd shall bless you to prosper far beyond your fathers.’ The 5,727th verse, corresponding to the Jewish year of 5727 and the secular year of 1967, reads, ‘And the L-rd shall do to them as He did to Sihon and Og, the kings of the Amorites and to their lands, that He destroyed them.’ Unfortunately, for the leadership of the Israeli Army, it was pretty much kochi v’otzem yadi. General Shmuel Gonen — who was born frum in Mea Shearim but went off the derech — was asked if, while on the battlefield, he ever looked up to Shamayim. He said no, he only looked left and right to see how many tanks he had.”

You gave several chapters in the book to how the Israelis were caught off guard, even though there were warnings right up until Yom Kippur morning. What happened?

“The intelligence failure offers a textbook example of a common phenomenon, in which people believe in a set of core assumptions, and then follow those assumptions into disaster, even though there is ample evidence to the contrary. In 1941, for example, the US Navy did not plan for an attack on Pearl Harbor because its admirals didn’t believe that the Japanese Navy had the capability to strike so far from home. In 1973, the Israelis were convinced of what became known as the Conceptzia, or ‘The Concept.’ It said that Egypt would not go to war until it received advanced fighter jets from the Soviet Union. Since those jets were not scheduled for delivery until 1975, Israeli Intelligence thought it had some breathing room. Moreover, the Egyptians mobilized and demobilized their army 23 times in the year before October 1973. So even seeing an army mobilized on the border was hardly a tip-off that war was about to break out.”

What was the main turnaround factor in the war, after such heavy Israeli losses? How did Israel regain its footing? Was that also an open miracle, or was there a rational explanation as well?

“Researching the war reminded me of the neis nistar of Purim. There is nothing in Megillas Esther that, strictly speaking, is not according to the natural order. But when you connect all the dots of the story and see the turnabout, v’nahafoch hu, you have to see the Yad Hashem. I think of the Yom Kippur War in the same way. Why did the Egyptians leave their southern flank completely exposed, allowing the Israelis to cross the Suez Canal right under their noses? Why did Syrian tanks stop in the middle of the first night, when they could have driven unopposed down to the Jordan River? These things have caused all manner of conspiracy theories in the Arab world — and even a few in Israel — because they really have no rational explanation. Now, for those who wish to find a more rational explanation, there is the unbelievable mesirus nefesh of the soldiers, never giving up. The Israelis have a saying: ‘When it rains on you, the enemy is also getting wet.’ That is to say, when you’re in the heat of battle, and you’re hungry, tired, and out of ammunition, it’s just as hard for the soldier on the other side. The side that holds on just one minute longer is the side that wins. In many of the key battles, the Israelis won because they held on just one minute longer.”

When the Six Day War was over, Israel was left with its heartland, Yehudah, Shomron, Sinai, the Golan Heights, and a united Jerusalem. In the end, what were the gains out of the Yom Kippur War (besides surviving and fending off the enemy)?

“In the war’s aftermath, the Arabs had a stark choice: make peace with having lost the pre-1967 lands, or make peace with Israel. Sadat chose to make peace with Israel, and thus received back the Sinai Peninsula. Both Hafez el-Assad and his son Bashar chose not to make peace with Israel, and so Syria never got back the Golan Heights. It can now be said with near certainty that it never will.”

What about the international alliances? Who were Israel’s allies, and who was egging on Egypt and Syria? In the end, which superpowers came out ahead?

“The United States backed Israel while the Soviet Union backed the Arab states, primarily Egypt and Syria. The conflict became a huge Cold War victory for the United States. American weapons triumphed over Soviet weapons on the battlefield, while Washington showed that it could offer its ally far more material support than Moscow could ever match. It’s no coincidence that after the war, Egypt ended its alliance with Moscow and turned to Washington instead. Egypt remains a close ally of the United States to this day.”

The first shots that started the Yom Kippur War were fired in the early afternoon, just as the soldiers manning one of the forward posts were reciting Unesaneh Tokef in their makeshift minyan, never considering that in a few minutes they’d be on the frontline of a raging war. Some of those men were inscribed in the Book of Life, while tragically, many others were not. As we gather in shul this Yom Kippur, 50 years later, perhaps we take a few moments to pray for their souls as well.

Excerpt:

Information at a Bargain

Sometime in 1969, a tall, handsome, impeccably dressed man walked into the Israeli embassy in London and asked to speak to a Mossad agent. “I want to work for you,” the man said. “I will give you information that you could only hope to obtain in your wildest dreams. I want money, a lot of money. And believe me, you will be happy to pay.”

The Israeli intelligence community was indeed happy to pay. When word made it back to Tel Aviv, the heads of Mossad and Military intelligence practically fell out of their chairs. Through the 1970s, they would pay the staggering sum of $3 million — equivalent to over $20 million today — and those in the know considered it a bargain. For the individual who offered his services was no less than the right-hand man of soon-to-be Egyptian president Anwar Sadat.

Caught by Surprise

The shelling was intense everywhere else, and so was the surprise. An enraged Israeli colonel ran outside at the outbreak of war demanding to know who commenced fire without his authorization. (The Egyptians, was the reply.) The dust cloud created by the bombardment was so thick, the men reported — falsely as it turned out — that they were under a gas attack. The soft sand of Sinai absorbed much of the explosions and shrapnel, creating a strange ripple effect across the landscape. One witness said the ground itself got up and danced.

At the same moment, the Syrians let loose a similar barrage on the Golan Heights, firing an estimated 25,000 shells in the first five minutes of the war. The ground was firmer in the Golan, pushing the force of every blast higher into the air. The clouds of black smoke they created hung over the battlefield for three days.

Intelligence officers listening to Egyptian radios only barely heard the blasts in the background. They were drowned out by thousands of men descending to the Canal shouting Allahu Akbar!!

Empty Skies

A young soldier was manning a radar screen on Mount Meron, near the ancient city of Safed. “Hey, Cafri,” she said to her superior, “I might be having a technical problem, but it looks like dozens of Syrian planes are heading toward the Golan Heights.”

Major Yair Cafri initially went into denial, not unlike a patient given a terminal diagnosis. It was probably just a technical glitch, he told her. But then he overheard one of his assistants breathlessly telling an air base to scramble fighters. Now shocked into reality — and with radar screens filling tighter with flashing lights — he quickly wired the air defense duty officer and told him to fire his Hawk surface-to-air missiles at every bogey in the sky. Like the Arab SAMs, the American-made Hawk missiles could not distinguish between friend and foe. “Are you sure you want me to do that?” the missile officer asked incredulously. Cafri repeated the order: Shoot at every plane on the screen.

Major Cafri, the radar’s commander, was perhaps the first to realize what would soon horrify those above him. War had broken out, and the Israeli Air Force had hardly a single jet in the sky.

Mobilized civilian buses carrying IDF troops across the Canal. Israel had been securing the east bank, the Sinai side, since 1967, but now they were facing off with Egypt on foreign turf

The Killing Zone

It is Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest who is credited with saying that military victory was about getting there “firstest with the mostest.” The adage was as true in 1973 as it was in the American Civil War. On the evening of October 6, Egyptian troops reached Israel’s battle ramps first. From there, they fired “the mostest,” thousands of RPG rockets and missiles. Against that, the Israelis violated the two cardinal rules of tank warfare, which are to never stand still in an enemy killing zone, and never attack one at a time. Israeli tanks split up and rolled into battle in tiny groups, coming to a stop near the maozim (a string of miniature forts along the Suez Canal, each one heavily fortified and supplied with periscopes to allow soldiers to safely view what was happening outside and direct tanks to enemy positions). One battalion commander received a desperate report from the field, “They’re shooting at us with missiles that have wires. The missiles are chasing us and hitting us.” And then the radio went dead.

It was only the following morning, October 7, that the Israelis understood the mistake of making the maozim lookouts their strategic focus instead of stemming the Egyptian invasion. The casualty reports spoke for themselves. One of the three brigades permanently stationed along the Canal, the 401st, entered the battle with 98 tanks. By the following morning it was down to just 25. Another brigade, the 14th, started the war with 100 tanks. The next day it was down to 14. Less than 24 hours had passed since hostilities began and the Israelis had already lost 173 tanks, or almost ten percent of their entire arsenal.

Just Five More Minutes

Once Commander Avigdor Ben-Gal called in his reserve, there would be not a single tank between the valley and northern Israel. He called it in anyway. He wired Lieutenant Colonel Meshulam Retes and ordered him to reinforce the Hermonit with whatever he had, which turned out to be just eight tanks, the remainder of a battalion that started the war with 36. Retes was one of the IDF’s old war horses, who had befriended Ben-Gal when the latter served under him earlier in their careers. Retes met Ben-Gal in the field and told him, “This is a suicide mission and we both know it. If anyone else gave me his order I’d refuse it. But you’re asking, so I’ll do it for you.” With those words he closed the hatch on his tank and rolled off into battle. He took a direct hit an hour later and was killed instantly.

At around noon, after five hours of combat, Lieutenant Colonel Avigdor Kahalani, commander of the force on the Hermonit, ran out of ammunition. Kahalani moved off his position to look for a second line where they might retreat. Realizing that there was no such place, he told his driver to return and position the tank in a prominent place. Perhaps seeing a tank would scare the Syrians off. A sister battalion likewise ran out of ammunition. Its commander, Captain Meir Zamir, filled his pockets with grenades and prepared for a last stand.

Ben-Gal radioed General Eitan. His men were out of ammunition. They had no choice but to withdraw. Eitan pleaded with him to hang on for just five more minutes, certain that the Syrians would break first. He also promised reinforcements, though Ben-Gal was convinced these were reinforcements he did not have.

Shortly after that, a soldier from the crack Golani Brigade radioed in from Outpost 107, which was well behind enemy lines. The Syrians were retreating.

Avigdor Kahalani emerged from his tank. He looked down at the hundreds of burned bodies and vehicles strewn before him in the valley, smoke rising, air filled with the stench of cordite and burning flesh. He said, “It looks like a valley of tears.” The statement reached a reporter for the IDF newspaper, Bamahane, Israelis have known it by that name ever since. The Syrians know it as the “Wadi of Death.”

The battle passed on into Israeli lore, joining the 1948 Battle of San-Simon and others in which the IDF won, by virtue of holding on just one minute longer than the enemy.

Once the Air Force regrouped, the fighter planes provided air cover for infantry troops on the Golan Heights

Light Up the Battlefield

Meanwhile, on the afternoon of October 12, Elazar convened the senior leadership of the government and the army — 18 people in all — for what he called “a very, very fateful decision.” Elazar reviewed the dire situation of planes and tanks before concluding that Israel needed a ceasefire and needed it badly. But what if Sadat refused? Should they attempt to cross the Canal? Practically the only criterion for the decision, he said, was whether a crossing made a ceasefire more or less likely. Elazar said that he had not yet made up his mind himself.

The opportunities west of the Canal were obvious. A tank force, once set loose, could destroy the SAMs or at least cause them to retreat, thereby opening the skies to the Air Force. Seemingly, this was the only way to defeat the Egyptian Army and avoid a war of attrition. The trouble was that Egypt had 550 tanks west of the Canal, and the most the Israelis could send was 400. This was hardly a favorable ratio for an attacker. Worst of all, Israel had only one heavy bridge — the so-called “rolling bridge” — and two vulnerable pontoon bridges. If they were destroyed, the force west of the Canal would be cut off. “Let me ask an idiotic question,” Golda said, “where could we get a bridge if we needed one?” Elazar explained that the only source was the Americans, but they would never supply one because it was deemed an “offensive weapon.” Dayan added that if the attack failed, and a large force was lost west of the Canal, they might find themselves fighting outside Tel Aviv. General Tal added that in all their war games, the IDF assumed it was controlling the east bank of the Canal. No Israeli soldiers had drilled battling to the Canal and then crossing under fire. Something this complicated was not the sort of thing you could improvise in the field.

As he spoke, someone knocked on the door and asked Mossad Chief Zvi Zamir to step outside. The others in the room, nervously chain smoking, could barely hide their annoyance. What could he possibly have that was more urgent than the matter at hand?

He soon returned with news that more than justified his brief absence. The Egyptian Officer who had been passing secrets to Mossad reached out. Egypt was about to helicopter three brigades of commandos to the passes. Zamir immediately understood what that meant: An offensive was coming.

Zamir had his aide rush to the Mossad office nearby and bring the file containing Egypt’s war plan. The plan, which Mossad had carefully stitched together from multiple sources, called for Egyptian commandos to block the passes while 900 tanks attacked east to hook up with them. To carry this out, the Egyptians would have to move between 200 – 300 tanks from the west bank of the Canal to the east. Once that happened, the ground west of the Canal would be undefended, vulnerable, and ripe for an Israeli attack. As for the ground east of the Canal, the Egyptians would be sending 900 tanks against Israel’s 700. “With a ratio like that,” General Tal declared, “we will light up the battlefield.”

All the fear drained out of the room. Golda spoke for everyone. “It would appear that Zvika [Zamir] just settled the debate.”

Smoldering Death

The flat moonscape of Sinai seemed to be torn open to reveal the earth’s inner organs. Fire and smoke erupted from the desolation, sending black pillars into the skies. Ariel Sharon, now in his fifth war, declared it “the most terrible sight I had ever seen.” Moshe Dayan said the same thing. The smell of cordite, scorched flesh and burning metal hung over hundreds of blackened vehicles of every size. The twisted, smoldering wrecks left little doubt as to what happened to the men inside at the moment of calamity. At least 108 Egyptian tanks were destroyed against about 50 Israeli tanks; many had their barrels interlocked in the armored equivalent of hand-to-hand combat. An Israeli who survived by pretending to be dead had a gold chain pulled off his neck, and witnessed Egyptians going from tank to tank shooting survivors.

Seeing the difference between what happened to soldiers on the east bank of the Canal from those on the west, a medic was reminded of the selections the Nazis did at the entrance to concentration camps. Those sent to one side lived and those sent to the other died. The bodies were so severely burned that it was often impossible to tell who was Israeli and who Egyptian. A medic worked across the battlefield asking, “Are you a Jew? Are you a Jew?” A sound came up from a blackened, ash-covered man with a mangled right hand missing some fingers. He turned out to be Yitzchak Rabin’s nephew.

“I am a Jew,” he said. And then he sighed. “It’s hard to be a Jew.”

Dancing Through the Night

On the afternoon of October 17, Itzik Mordechai assembled what was left of the 890th Parachute Infantry Battalion. There was a fearsome battle forming around the Canal bridgehead, he said. He would not order anyone back into the fight, not after what they had been through in the Chinese Farm. Any man that wanted to leave could do so and no questions would be asked. But the entire war effort depended now on keeping the corridor open and every able-bodied soldier was needed. Not a single man left.

As the paratroopers were about to set off into the night, the unit’s unofficial “combat rabbi” — the IDF had no such title, but he fought through the night and he was a rabbi — asked Mordechai to halt the operation. Like everyone, he had lost track of time. But he did a quick calculation and came to a realization. It was the Jewish holiday of Simchas Torah. He ran back to the equipment truck, emerged with a Torah in hand and began to dance. Two men joined him, and then two others. Before long, the shattered men of the 890th were holding hands, singing and dancing in a circle. The celebration continued through the night.

Long-range artillery action on the Syrian front. It was a question of who would hold out a few minutes longer

Between Victory and Defeat

While flying to the Kremlin, Kissinger was given news of a development that in his words, “turned almost into an obsession for the next five months.” Saudi Arabia declared a total embargo on oil exports to the United States. Coming on the heels of the October 16 price hike and the October 17 five percent cutback, the psychological effect on markets was electric. Panic buying ensued. By mid-December oil was selling for $17 a barrel — six times the pre-October 16 price.

During the Cold War, conflicts typically ended after years of negotiations. The Moscow talks lasted only four hours. The Soviets capitulated on every substantive issue. What the Soviets got in return was speed. The draft resolution would be presented to the UN Security Council immediately. Once it passed, shooting had to end “no later than 12 hours after the moment of the adoption of this decision.”

Under ordinary circumstances, Israel would have considered this an excellent deal. But these were not ordinary circumstances. As Kissinger knew from State Department reports, the quick ceasefire would prevent the Israelis from encircling the Egyptian Third Army. As Jerusalem saw it, only a few more hours separated victory from defeat. There were two east-west roads from Cairo used to supply the Third Army, and a third coming up from the south. The Israelis had captured the two east-west roads. If the third eluded them, then the Third Army would soldier on and the Israelis would find themselves fighting a war of attrition from overextended lines deep in Egypt.

* * *

The talks dragged on for days with Kissinger shuttling between the State Department where he met with Fahmi, and Blair House where he met with Golda. The Egyptians were adamant that Israel had to pull back to the October 22 ceasefire line. “She cannot bargain on the return to the October 22 positions,” Fahmi insisted. “The Security Council has decided the matter.” Golda stiffened her back and refused. Israeli soldiers would stay put. They would allow supply of the Egyptian Army, but only if POWs were exchanged. Israel would only negotiate a full separation agreement, and only while the Third Army was surrounded.

Late on November 3, Kissinger finally lost patience with her, stressing what a challenge she would face, “explaining to the American people how we can have an oil shortage over the issue of your right to hold territory you took after the ceasefire.” He also pointed out how important it was to get a deal done now, so they could all get through the winter. “Oil pressure in April is different from oil pressure in November,” he said.

Golda wouldn’t budge.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 979)

Oops! We could not locate your form.