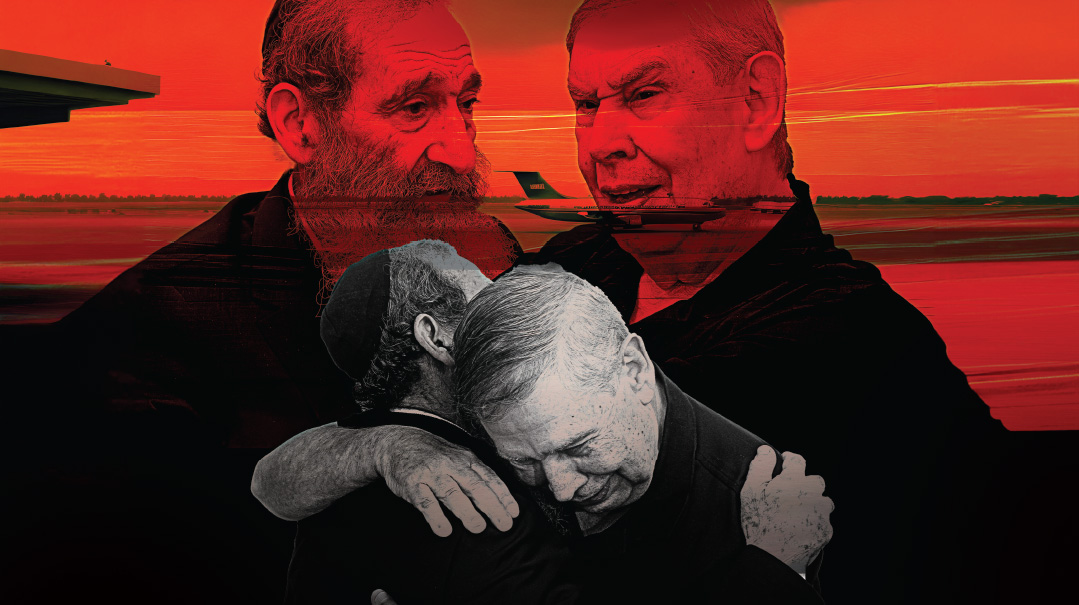

Two-Part Harmony

Veteran badchan Yonasan Schwartz sings for new couples by night and repairs frayed marriages by day

Photos: Itzik Roitman, Mishpacha archives

Longtime badchan Reb Yonasan Schwartz never takes the Yiddish expression “you can’t dance at two chasunahs” literally. Just before this last Pesach, he was thrilled to dance at two weddings the same night — not that he’s looking for extra simchahs, considering he leads the mitzvah tantz many nights of the wedding season. But these simchahs were extra-special to him, the unexpected fruits of his passionate speeches, talks, and recent clips begging couples to try every avenue of resolution before — or even after — deciding to end their marriage. Indeed, these were weddings of “machazir grushaso” — remarriage to one’s wife after divorcing.

He has no official title or shingle hanging from his window, but the owner of Brooklyn’s Toys-2-Discover toy store chain by day and wedding grammer by night (although after three decades he says he’s slowing down) has been producing widely-viewed weekly video clips for the last three years, sharing his thoughts on shidduchim, shalom bayis, the tragedy of throw-away marriages, divorce and parental alienation.

Because really, no one has a window to the minefield of family dynamics like a skilled mitzvah tantz badchan, who has to keep the peace all around, show honor to all sides and be very funny and entertaining without offending anyone.

Reb Yonasan always knew his mouth was his most powerful tool, although he assumed that only went as far as the dance floor. But it was during the Covid lockdown that he discovered people were interested in what he had to say even if it wasn’t in rhyme or grammen. His insights into shalom bayis, divorce trauma, parental alienation and the ubiquitous shidduch crisis are profound — and really, what else would you expect from someone who’s spent most nights for the past 35 years navigating complex family relationships while sending new couples into their future?

“A good badchan is really a family therapist,” Reb Yonason says. “He has to be highly intuitive and very quickly tune in to the nuances of the family dynamics. With a few words, he has the capacity to make shalom between relatives or fan the flames of machlokes. I don’t even know most of the families I do weddings for, but after doing this for more than three decades, an hour of gathering family details from a few different sources is usually enough for me to know what to say and what not to say.”

A “badchan” is loosely translated as a “jester,” but a family who commissions one for their child’s wedding knows it’s so much more. At a chassidic wedding, the badchan is the link between generations, weaving his verses as he summons the honored relatives to the mitzvah tantz — a dance that, according to tradition, joins the souls of those generations together. And as the two halves of the soul — husband and wife — have found each other, it is also a mirror of something cosmic — a dance of the Jewish People reuniting with the Shechinah.

And that’s why it’s so painful for Reb Yonasan to see marriages breaking up, as well as so many singles waiting to find their zivug. On his popular weekly clips, those are the topics that get the most traction. In fact, he’s even started his own campaign: It’s called ShidduchCall, and it’s a sort of matching campaign, although with a different currency. Instead of money, “donors” pledge hours to network for their friends. Within a year of its creation, hundreds of successful shidduchim have already come about.

It started when he talked on the shidduch hotline “Leshadech” last year, after which he says he received dozens of calls from broken parents asking him for some eitzah to help their children find shidduchim. He tells of a 29-year-old bochur in Eretz Yisrael whose friends, eager to help him, got together and offered a certain very busy and popular shadchan $20,000 to find him a shidduch. The shadchan had a better — and cheaper — idea: that each one of those friends pledge at least 20 minutes every day to work the phones on behalf of this bochur. One week later, he was a chassan.

“We’ve created a matching campaign — not with money but with the most precious currency — your time,” Reb Yonasan explains. “Look, I know what it means to be busy. I have five retail stores, a wholesale business, I do weddings and I visit the hospital once a week. I have no time, and you have no time. But just pick up the phone and do it, and G-d willing, you’re going to see success.”

For badchan and motivator Yonasan Schwartz, helping people find their zivug is only half the challenge. Helping them stay married is the other half

The Last Resort

For Yonasan Schwartz, helping people find their zivug is only half the challenge. Helping them to stay married is the other half. Not a week goes by without Reb Yonasan publicly lamenting the scourge of divorce in the Orthodox/chareidi community, especially for those couples — challenged as they are in their relationships — whom he’s convinced could have, and can still, make it work.

“I meet so many wonderful people — successful, financially stable, with great kids. But they’re living alone,” he says. “They were sure that right after they divorced, the next zivug was just waiting for them around the corner. Since then, a year, two, five and ten years have passed and it turns out that, with all due respect to their status, family or yichus, they’re still alone.

Reb Yonasan doesn’t profess to be more than he is — he’s not a family therapist or a psychologist, and he has no organization behind him — yet he has a message and a mission, about 6,000 followers a day on his status, and has found himself to be a magnet for hundreds who’ve reached out to him, confident that they can unburden themselves with empathy and without judgment. And what he’s culled from those conversations is that if someone thinks they simply can’t push through anymore and that a different home will be easier, often that second home involves even more compromising and self-negation. Divorce, he believes, should be a last resort when there’s really no way forward.

“Just recently,” says Reb Yonasan, “a woman who’s separated from her second husband called me and told me, ‘I’m really sorry I divorced my first husband. There was a lot of ego, a lot of brainwashing from well-intentioned people who became involved, but I just want to tell you that my second husband made me miss my first husband. Had I known what I needed to give up on and compromise to marry a second time, I wouldn’t have gotten divorced in the first place. I would have done everything possible to keep our home together.’”

“I see this much too often,” he says. “As a candidate for a zivug sheini, the zivug rishon suddenly looks pretty good.”

Reb Yonasan isn’t a marriage counselor, and cringes at the idea that some consider him a “shalom bayis macher.” “I’m simply a motivator,” he says. “I consider it my responsibility to bring awareness. Sometime just making noise about it is enough to put it on the communal agenda.”

He doesn’t necessarily discourage people from remarrying — more than 25 years ago, as a father of young children, he himself went through divorce and remarriage. And while he and his wife have built a warm, blended family, he intimately knows the challenges in real time. He says he wants to get people to think a little more, to consider compromising a little more, before taking drastic and often irreversible steps.

While Yonasan Schwartz has woven together thousands of people’s life stories on the wedding floor over the years and is never at a loss for words, he says his new, broad following actually came as a quite an unintended surprise. It started quite by accident when he sent one Torah-oriented pep talk with an idea culled from that week’s parshah privately to a friend who was going through a rough patch. That friend sent it on to someone else, and before he knew it, hundreds — maybe thousands — had seen it and were talking about it. (The message, he remembers, was in part related to how an eved ivri becomes rehabilitated in a healthy environment, and that a similar change would help his friend as well.)

“That Friday night in shul,” he recalls, “someone came up to me and said, ‘What, you think you became a maggid shiur?’ But I wasn’t offended — I was actually happy that so many people had seen it. And so I decided to do a short clip every week. I don’t even take the credit — Hashem gave me a certain skill in relating positive, inspirational messages to people who are struggling.”

Reb Yonasan has perfected the art of giving honor and a rightful place to all members of a complex family web

No Hard Feelings

As a badchan who sometimes has to navigate the tension in conflicting sides of the wedding party, he’s often a witness to the messy underbelly of divorce: the fallout for the children and the all-too-common and tragic family dynamic of parental alienation, when one parent tries to manipulate a child’s rejection of the other parent. The alienating parent cultivates extreme negativity toward the targeted parent by sharing with the children deprecating comments, all-encompassing blame, and false accusations. This parent usually hoards the kids as well, doing all he/she can to create a strong (and generally unfounded) sense that it’s dangerous/unhealthy/scary/awful to be with that parent.

“I’m not saying that breaking apart a family is never an option. It happens, it sometimes has to happen, and Hashem Himself gave us the tool for it in the Torah,” Reb Yonasan clarifies. “But even when it comes to divorce, when there’s no other option, there is no reason for parents to lose their human dignity and turn on each other like predators, and there’s no greater damage to a child than one parent alienating the other.”

Sometimes, he says, that alienation comes back to slap the alienating parent in the face. He recalls a wedding in Monsey a few years back, in which he was hired to be the badchan for the mitzvah tantz.

“I came to the hall and the chassan’s mother called me out. ‘Look,’ she said, ‘something happened. The chassan’s father, my ex-husband, came to the wedding. If you mention one word about him, you won’t get paid a penny.’

“I heard her warning and walked into the hall. From a bit of schmoozing here and there, I was able to put together the story: This couple got divorced even before the son, the chassan, was born. The woman remarried, and the boy grew up without knowing that the person he thought was his father was not his biological parent. The real father also remarried, yet after his ongoing efforts to reach out to his bechor were continually rebuffed, he gave up and focused on the children he had at home.

“Everything seemed to be at peace, but Hashem had His plan. This bochur went to learn in Eretz Yisrael, and it just happened that he was placed in a dorm room with a cousin of his real father. This cousin heard his name, connected some other bits of information and then told his new roommate, ‘You’re not Weiss, you’re Schwartz.’ ‘What are you talking about?’ the boy replied, ‘I’m Weiss.’ ‘You’re not Weiss,’ the new friend insisted. ‘You’re Schwartz. You have a different father.’

“The bochur called his mother, who initially fumbled but eventually was forced to confirm to her shocked son, that indeed, he was the son of a different father. ‘But don’t you dare even think about him,’ she said. ‘He’s cruel and a real rasha. He never wanted to have anything to do with you.’

“But from that moment, the bochur made it his business to try to complete the puzzle. He discovered that his father was a successful mechanech who had a sterling reputation in his community. With the help of his roommate (and newly-discovered cousin), he bravely made contact, father and son began to speak by phone, and eventually they met in person.

“When it came time for the boy’s wedding, the father came at the request of his son. But then, a commotion ensued,” Reb Yonansan continues. “The mother didn’t want him there, and warned me not to mention him in my grammen. But I knew I had to do the right thing.

“For an hour, family members and others circulated around me, threatening, warning, pleading. But I knew what I had to do. At 12:30, I went into the family circle and proceeded to pull off one of the most emotional mitzvah tantzes I’ve ever done. I mentioned the father who yearned for his child through the years, and how their paths crossed with Hashgachah pratis; I also praised the stepfather for investing so much in the chassan over the years, and of course, focused on the mother who wanted the best for her son. Tears rolled down everyone’s faces. Kisses, hugs, and the event was over.

“Well, not exactly. This was just the beginning. Because when I met the mother a few months later, she asked me to try and convince her son to come back to her. He was so hurt by the fact that she had prevented him from being in contact with his father over the years that he couldn’t bring himself to forgive her. And unfortunately, the story is still not over. Because despite all the years that have passed, the harsh feelings remain.”

Thirty-five years as a badchan has given Reb Yonasan a window in all kinds of family dynamics. At the wedding of a great-granddaughter of Rav Wosner ztz”l, “when I called the Rav to the mitzvah tantz, I begged him to daven for Klal Yisrael”

No Less a Father

Reb Yonasan Schwartz’s unusual gift of a gilded tongue off which the most profound lyrics spontaneously roll, coupled with his sweet, relatable voice, has kept him comfortably ensconced for decades in the chassidic music industry. His popular series of Yiddish recordings beginning in the 1990s (A Gutte Voch, A Gutten Shabbos, A Gutte Shuh, A Gutte Besurah, A Gutter Yid, A Gutte Niggun, A Gutte Neshamah, A Gutte Hartz, and A Gutte Brachah) contain songs of joy and connection, ballads that can bring a person to intense feelings of spiritual longing, and others that make one smile at some of the foibles of human nature and modern society.

(Although he bemoans the fact that today’s digital technology has essentially destroyed the business and few are putting in the effort and expense to produce new albums, he’s actually working on a new collection to be released shortly. He’s not expecting it to turn a profit, but says that “people find my songs to be positive and helpful, and this new album especially has many positive messages for people — I’m excited that I can share them.”)

But as his longtime fans know, every song also has its surprise: In one, called Unteren Chuppah (from A Gutte Besureh) he tells the story of a boy about to be married, whose father is deathly ill. As his wedding day approaches, the chassan begs his father to promise that he will escort him to the chuppah. “I promise that your father will walk you the chuppah,” his father responds. Shortly before the wedding, the song continues, the father passes away. The chassan falls on his father’s fresh grave and cries, “You told me that you would walk me to the chuppah!”

His father appears to him and says, “I promised that your Father would walk you to the chuppah, and he will. Hashem is the Avi Yesomim, Father of the orphans, and He will escort you to the chuppah.”

The song, like so many in his repertoire, isn’t so far off from his own life experience. Because his own personal challenges — from the time he was a young orphan growing up in Jerusalem — are often his biggest inspiration and have made him a true master of empathy, granting him the ability to connect to the pain and struggles of his listeners.

Reb Yonason’s mother passed away at age 31, when he was just ten years old. He was in and out of yeshivah and couldn’t quite find his place, yet Yonasan and his sisters were looked after by the Belzer Rebbetzin, a childhood friend of their mother, who promised the dying Mrs. Schwartz that she would care for the children. The Rebbe, too, never let young Yonasan out of his sight, despite the young bochur’s struggles. At age 20, he became engaged to a girl from Boro Park, and as a chassan newly arrived to the US, he, too, went to the chuppah without a parent.

Yonasan Schwartz didn’t speak a word of English when he landed in New York (hard to believe today considering his now comfortable and articulate English). With no support forthcoming, he took on a menial job that kept him busy from eight a.m. to eight p.m. Yet he loved to sing, and occasionally performed at weddings after hours — until his boss said to him, “What are you doing here? You belong in a studio. Go sing!” And so, six months later, Yonasan Schwartz the badchan emerged.

But his big break came three years later, in 1992, at the wedding of the Belzer Rebbe’s only son. Top badchanim were appointed to entertain the crowds at the mitzvah tantz and the week of sheva brachos. When Yonasan, who flew back to Eretz Yisrael for the wedding, filed past the Rebbe for a brachah, the Rebbe said, “Nu, and when are you going on stage?” “I don’t know, I wasn’t invited up,” he told the Rebbe. On the spot, the Rebbe appointed his former ben bayis to the Motzaei Shabbos sheva brachos.

“As I began to sing about the Rebbe, I noticed that a little boy, whose father had been killed in a car accident, hopped onto the Rebbe’s lap,” Reb Yonasan recalls, describing how he began to weave one rhyming couplet after another. “I faced the Rebbe and sang, ‘this is not only about zechus avos, but about the zechus of young boys you’ve merited to raise.’ There was another little boy there, but both the Rebbe and I knew what I meant — the little boy was really me.”

Reb Yonasan isn’t shy about discussing the challenges he’s faced, which he says have attuned him to the subtleties of people’s emotions and inner turbulence — and especially regarding his latest campaign of holding families together. In the mid-1990s he went through his own painful divorce, and wound up with custody of three small children. He was a single father for three years, until he remarried and built another family. He also lost three younger sisters within a two year span, each of them leaving families with young orphans.

For Reb Yonasan, every mitzvah tantz means another encounter with the complexities of a family unit he may have never even met before. But even after more than three decades, he still feels an emotional charge every time he calls up the mechutan.

“It’s a huge responsibility, because it really is the most dramatic part of the wedding — all the previous generations are there joining in. It could be the most cold-blooded family, but come the mitzvah tantz, their hearts melt.”

The most impactful mitzvah tantz he ever performed? That, he says, was 14 years ago in Switzerland, at the wedding of his own stepson — the boy he raised from age nine. And it was really about practicing what he’s been preaching: giving honor and a rightful place to all members of a complex family web.

“I called up the chassan’s father, my wife’s ex-husband, to the mitzvah tantz — I’m not exaggerating when I say there wasn’t a dry eye in the hall, and I want to share this because it’s so important for people to know that even if a family has to break up, you don’t have to be in a fight forever. When I called him up, I said that there are three partners in raising a child — two parents and Hashem. But sometimes there needs to be a fourth partner, and that’s okay.

“You see, when I remarried, I contacted my wife’s former husband and told him, ‘You’re the child’s father, one hundred percent, even though Hashem gave me the zechus to raise him in my home.’ And indeed, he was a full partner. I made sure that my stepson called him every Erev Shabbos, and that at every joint simchah, he sat at the head table.

“At the mitzvah tantz, I gave a parable about a Yid who ordered a sefer Torah from a sofer, but when the due date approached, the sofer realized he wasn’t meeting the timetable: He still had entire yerios that he hadn’t finished. So he went to a different sofer and told him, ‘You start writing the final yerios and together, we’ll complete the sefer Torah.’

“‘This sefer Torah,’ I said through my own tears, ‘was completed by both of us. Each of the fathers gave his part, as long as we merited together to write a mehudar sefer Torah that is now establishing its own aron kodesh.’

“This chassan is today a gifted mechanech in Lakewood, and he’s also a successful therapist. I’m not saying there are no scars, but we did the best we could. In fact, the morning of the wedding, my stepson called me in and said, ‘Tatty, thank you for everything, but most of all, thank you for being such a good father and yet never making my own father feel like less of a father.’ ”

After speaking at an evening for boys from broken families, Reb Yonasan was inundated with requests from divorced parents to help them find a way out of the quagmire

Still Family

While parents at the helm of blended families often struggle with perceptions — sometimes misguided — of the fear of instability stemming from dual loyalties, Reb Yonasan is adamant that the supervising parents do their maximum to ensure proper kavod for the biological parent. After being the featured speaker a few months back at an evening for Lev Leyeled, a support organization for boys from single-parent or broken families, his talk went viral and he was inundated by requests from divorced parents to help them find a way out of the quagmire they’d created in relationships between their children and their former spouse. These parents who reached out wanted more civility and kavod, and to find a way to put down their boxing gloves.

And their children, more than anyone, crave that level of peace. “Over the last few months, this has become the main conversation around me,” Reb Yonasan says. “A 21-year-old bochur I’ve been in touch with told me, ‘I can’t understand why my parents didn’t just shoot me when I was a seven-year-old, before they got divorced. Better to have been dead.’

“It really comes down to one non-negotiable fact,” he continues. “From the moment one becomes a parent, no one can withhold from that person the connection that Hashem made between him and his child. And even if we agree that this parent was not a good husband or she was not a good wife, that doesn’t mean he is a bad father or she is a terrible mother. I know many couples who didn’t succeed in the area of shalom bayis, but love and are devoted to their children. A parent who prevents their child from being in contact with the other parent due to revenge or a desire to hurt their ex is, in my opinion, an abusive parent.”

Typical alienation strategies include poisonous messages to the child about the targeted parent in which he or she is portrayed as unloving, unsafe, and unavailable; limiting contact and communication between the child and the targeted parent; erasing and replacing the targeted parent in the heart and mind of the child by a continued litany of negative remarks; encouraging the child to betray the targeted parent’s trust; undermining the authority of the targeted parent, and forcing the child to choose loyalties (“If you pursue a relationship with him, it will jeopardize your relationship with me”). These tactics cause extreme internal distress and confusion to the child, and this is one of the most tragic and painful challenges for a parent.

That said, is it possible to maintain a healthy connection even when a spousal relationship was severely compromised and there’s bad blood between the sides? Reb Yonasan says yes. He mentions his good friend and colleague Reb Michoel Schnitzler a”h, who passed away the day after Pesach. “He was known to be a real mensch, and he would call his ex each Erev Yom Tov to wish a Gut Yom Tov even though he was divorced. That was the best example he could show his children, who saw that it was possible remain human.

“A divorced woman recently reached out to me for help in finding a shidduch for a second marriage. I tried to find out about her and reached her former father-in-law, a wealthy and well-known Yid from a particular chassidus. He heard that I was trying to find her a shidduch and told me, ‘If you find her a good shidduch, I’ll add $10,000 to whatever shadchanus you get.’ When he saw my surprise, he said: ‘Why are you surprised? She’s the mother of my two grandsons, my flesh and blood. And I want them to grow up in a healthy home. I want them to have a good father who will be devoted to them. I’ll even pay for a house.’ Since then, he’s been in touch with me, inquiring, advocating. That’s the healthy approach of a person who knows the right thing to do. He doesn’t let his sechel get railroaded by his emotions. He knows that he has to do everything possible to help the children grow up healthy and be able to be good parents to their own children. I don’t expect every person to pay for a house for his former daughter-in-law, but at least don’t fight. Work from the head. The children will only benefit from it.

“Because no matter what you think about your ex, the worst thing you can do to your children is incite against their parents, their grandparents, their aunts and uncles. If you think that by doing so, you’ll only cause the other side to suffer and anyway they deserve it, you’re wrong. The children are the ones who suffer and pay the price, and later, for the rest of their lives, you’ll also pay the price, and with interest. Because in the end, the resentment harbored by your child will harm not only his emotional health, but the future of your relationship.”

Reb Yonasan is a busy man, but he says he’ll do whatever it takes to help keep parents together, and even to help them recommit after separating. “I was at a bar mitzvah recently of a child whose parents were divorced and then got back together again. I was personally involved in that parshah, and as I walked into the hall, the bar mitzvah boy got up and enveloped me in a bear hug — he wouldn’t let go. It was a bit embarrassing, but I couldn’t get out of his embrace. He held onto me and sobbed, ‘You gave me my life back. I suddenly got back my family, my parents, my siblings. I got the Torah back — because before that I couldn’t learn, and now I can.’”

Yisrael Hershkowitz contributed to this report.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 967)

Oops! We could not locate your form.