A Tzaddik For Our Times

Rooted in a bygone era, Rav Binyomin Finkel soothes the ills of a new century

Photos: Eli Cobin, Menachem Weinberger, Baruch Yaari, Naftali Lerer, Family Archives

He’s the mashgiach of one of the mainstays of the yeshivah world, but Rav Binyomin Finkel’s own personality fuses classic mussar with chassidic warmth, and tempers rigorous introspection with an open heart for those far from his standards

It’s close enough to midnight that even in Itzkovitch, the Bnei Brak shtibel that doesn’t sleep, people are rubbing their eyes. The last daf yomi shiur of the day is winding down. A late Maariv is reduced to a hum, and the tzedakah collectors are thinking of calling it a day.

One man in the corner, though, seems remarkably unhurried. Clad in homburg and frock coat, he stands nestled against one of the pillars of the aron kodesh, lost in another dimension. Two minyanim have come and gone; the third will overtake him soon, and yet — as if it were Kol Nidrei night — he continues to quietly pour out his tefillah.

A half hour later, as the rav turns around and heads toward a waiting car, a knot of petitioners forms. “Harav,” says one bochur, “please give me a brachah to enjoy my learning.” A second approaches and asks for a brachah for a shidduch. “Does the rav remember my great-grandfather?” a third wants to know.

Despite the fact that the 70-year-old rav has spent a grueling day learning, giving shiurim, being mesader kiddushin in Bnei Brak, delivering a hesped near Haifa, and answering literally hundreds of questions large and small, he responds to each with a warm smile and genuine interest. From his tranquility, the eager questioners would never know that he’s hardly eaten for hours, or that his day still has a long time to run.

Welcome to the extraordinary world of Mirrer Mashgiach Rav Binyomin Finkel, someone whose childhood nickname — “Binyomin HaTzaddik” — rings true decades after his classmates first coined it.

Born into a family that was like a shelf of gedolim biographies, he is that ultra-rare phenomenon — an inheritor of the proverbial “row of zeros” of great yichus, who decided to put his own number in front.

Son of one great gaon, Rav Aryeh Finkel; leading talmid of an uncle, Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz; and heavily influenced by a saintly Yerushalmi grandfather, Rav Shmuel Aharon Yudelevitch, Rav Binyomin Finkel embarked on his own relentless path of growth that saw him emerge as something totally unique.

A childhood spent seeking out all the different flavors of greatness that were available a short walk from the Mir shaped Rav Binyomin into both a transmitter of his great forebears’ legacy, and a citizen of the entire Torah world — at home among Briskers as among chassidim and Sephardi chachamim.

Whether he’s walking out of the great fortress of Torah that his Mirrer predecessors built, or speaking in shuls from Zurich to Deal, New Jersey, the effect is the same: he’s mobbed by crowds seeking a brachah or direction on any number of questions. What are they drawn by? The advice he gives — daven, learn more, work on middos — isn’t new. But his authenticity, the way he utterly believes that these constitute the only road to success, is breathtaking in its clarity.

So, too, is his fusion of old and new. His roots lie in the bygone world of the great figures in whose shadow he was raised, but he’s a 21st century tzaddik — connected to a world where bochurim struggle with technology and can be elevated by a kumzitz.

Most of all, Rav Binyomin’s chein — a spiritual magnetism that draws others like moths hungry for the light of the flame — stems from an overflowing love for his fellow Jew. ahavas Yisrael is no mere slogan; he’s simply incapable of ignoring someone in need.

“My father was my primary influence.” Rav Aryeh was proud of the son who’d found his own path, while remaining faithful to his Mirrer heritage

Mashgiach of the Mir

Well before 12 noon, when kabbalas kahal begins, a line forms outside his small office on the ground floor of Mir’s famous main building. First, there are the cheder children, as groups come from all over the country to be tested on their learning.

Then at 12:30, come the regular slots. Bochurim can and do catch the Mashgiach at any time, before or after davening in the yeshiva or as he heads home or travels. But they make up a good proportion of the daily appointments as well. There are bochurim who want to discuss their situation in yeshivah, or are involved in a shidduch, and want the Mashgiach’s advice. He might just discuss things with them and then give a brachah, or he might pick up the phone and get involved to smooth things over.

Also in the line are avreichim, both from Mir and beyond. The Mashgiach has become a one-stop-shop for advice, counseling, and the boost to the spirit that his brachos provide. People come to him with health questions, shalom bayis problems, and for advice on struggling children.

I arrive as the line snakes from the Mashgiach’s door, through the little antechamber where his son sits, to the hat stands outside. There’s an interesting dynamic at work. People go in looking harried, and invariably emerge with a smile. Beyond the contents of the conversation, there’s something infectious about Rav Binyomin’s good cheer.

The many hours spent advising others in this room are besides his central function as mechanech from the lectern. The Mashgiach rotates between the main batei medrash of the Mir, delivering sichos in the storied main beis medrash, Beis Shalom, and the two floors of Beis Yeshaya.

Each of the venues, by definition, demands different content and delivery, tailored to the audience. Rav Binyomin will stay abreast of whatever the chaburos in that beis medrash are learning and any issues that are cropping up.

So he tailors the contents of a given shmuess to connect to the new perek. Or, if he hears that bochurim are forming ad hoc minyanim for Minchah in the hallway, for example, he might throw in a characteristically self-diminutive quip: “You’re such geonim that you can concentrate in the corridor, but what about normal people?”

A joint quest for regesh drew Rav Binyomin Finkel (pictured above at his sheva brachos) to Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz.

On Notice

The moment I walked into the Mashgiach’s room provided a good insight into the way that he cares for others. “Eliyahu,” he called out to Eli Cobin, one of Mishpacha’s steady cameramen, who accompanied me. “How are you?”

Eli happens to be a well-known figure, but beyond that Rav Binyamin notices people — especially people whom others don’t, the “little people.”

The photographers at weddings or public events are generally not meant to be the stories themselves – by definition, others take the center stage. Yet at event after event, Rav Binyomin makes a point to go and say hello. One events photographer recently asked the Mashgiach to be mesader kiddushin for him. The rav had simply said hello to him so many times that a relationship had formed from there.

The same happened with a waiter whom Rav Binyomin saw at a wedding. The boy was clearly a yeshivah bochur, but clearly vacillating, with one foot out of the door of the yeshivah world. So, the Mashgiach went over to exchange a few words. “Let’s stay in touch,’ he told the bochur, as he often does.

The boy got home and told his parents about the Rav Finkel and his offer to talk. They responded, “Do you know who that is? Go straight over there today and follow up with him!”

A short while after, he bashfully joined the kabbalas kahal line in the Mir, and a happily-ever-after ending ensued as the boy today is solidly growing in yeshiva, and still in contact with his friend, Rav Finkel.

The levaya for Rebbitzen Minna a”h, Rav Binyomin’s first wife, provided further evidence of the way that he thinks of others.

The day that she was buried was very hot. The large crowd who’d gathered were prepared to wait as long as was needed, but the Mashgiach had other ideas.

“I don’t want to speak for very long, because it’s hot,” he announced. “Drink, it’s important to drink,” he urged the assembled.

Like an old shtetl picture of a melamed with his beloved charges On a bein hazmanim trip to Israel’s north with former talmidim, Rav Binyomin stops off in a local shul to learn

Top of the World

A mountaineer once scaled a towering peak, and discovered to his amazement that there was a small child running around at the top. “What are you doing here?” the climber demanded. “I trained for weeks to get up here, so how did you manage?” “Simple,” replied the child, “I was born here.”

That story — told by the Chiddushei Harim to explain his grandson the Sfas Emes’s precocious greatness — comes to mind when contemplating the phenomenon that is Rav Binyomin Finkel, whose own special qualities were recognized by his peers early on.

The oldest of three sons and two daughters born to Rav Aryeh and Esther Finkel, little Binyomin was born into royalty. Rav Aryeh was a son of Rav Chaim Ze’ev Finkel, himself the eldest son of the Mirrer Rosh Yeshivah Rav Leizer Yudel, who in turn was a son of the legendary Alter of Slabodka, Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel.

Having arrived from Mir, Poland in 1926, in Mandate-era Eretz Yisrael, to join his grandfather, the Alter of Slabodka’s Chevron Yeshiva, Rav Chaim Ze’ev, put down roots in the local Torah world long before the wider Finkel family arrived during the Second World War.

Those roots included marriage into a Yerushalmi family — one of many bonds that shaped Rav Binyomin’s own very varied DNA. In fact, that’s one of the most underappreciated facts about this scion of litvish aristocracy: he’s half a “Tchalmer,” the term used for the caftan-wearing Old Yishuv communities steeped in Yerushalmi lore. It comes through in his conversation, which he peppers with English, and in his informality.

The first stage of that fusion came via his grandfather, Rav Chaim Ze’ev Finkel. Rav Chaim Ze’ev’s wife, Leah nee Eybeschitz, brought to the marriage an unusual spiritual dowry: a family relationship to the legendary rav of Yerushalayim, Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld. Leah’s mother, Chaya’leh, was first married to Reb Yehudah Leib Eybeschitz — a descendant of Rav Yonason Eybeschitz — and was 30 years younger than her second husband.

The Yerushalmi influence of that illustrious connection showed up in Rav Chaim Ze’ev’s choice of headwear. Slabodka rosh yeshivah Rav Dov Landau recalls that after his marriage, Rav Chaim Ze’ev Finkel — then a maggid shiur in Tel Aviv’s Yeshivas Heichal HaTalmud — began to wear a shtreimel when he spent time in Yerushalayim.

Of all his many teachers, it was Rav Chaim Ze’ev’s son, Rav Aryeh, who shaped his son most. “My father ztz”l was my first — and primary — influence,” says Rav Binyomin. “He was an illui who learned through almost all of Shas b’iyun with Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz. Along with the rosh yeshivah, Rav Chaim, and my zeide, Rav Shmuel Aharon Yudelevitch, these were who shaped me.”

The influence of Rav Aryeh Finkel — who served as rosh yeshivah of Mir Brachfeld — is discernible every day of the zeman in the Mir’s morning seder. If you head into the center-left section of the yeshivah’s main beis medrash, you’ll see Rav Binyomin deeply engrossed in learning the yeshivah masechta with his chavrusa, Reb Menachem Weinberg. “Unless there’s an emergency or he’s out of town, he’ll never miss first seder,” says the latter. “And he learns in the very straightforward, glatt way that he received from his father, focusing on a clear understanding of the Gemara, Rashi, and Tosafos. Like when he’s giving a shmuess, the Mashgiach’s recall of sugyos is phenomenal — he’s able to quote entire passages by heart.”

Rav Aryeh Finkel’s influence on his son is noticeable in externalities as well. Rav Binyomin’s long peyos and the fluent Yiddish that he speaks with his own children are unusual in today’s Israeli yeshivah world, where a more clean-cut look and Ivrit are the norms. They bespeak the Mashgiach’s upbringing in Kamenitz, a Yerushalayim institution with strong ties to the Yerushalmi community and generally more old-world feel. That, in turn, reflected Rav Aryeh Finkel’s own choice as a bochur to grow a beard — an uncommon sight in those days.

Such was the emotional bond between father and son that when Rav Binyomin sat shivah for Rav Aryeh in 2016, he asked to call an ambulance out of fear that he was having a heart attack.

It was in Kamenitz that a young Binyomin Finkel’s talents began to emerge — particularly his oratorical skills. At one stage, the cheder installed new restrooms. Naturally, in a school full of sharp Yerushalmi children, the occasion was merely grist for the humor mill.

A sign went up in the building — courtesy of the pupils — announcing the “Chanukas HaBayis” of the new facilities. The keynote speaker at the grand event was none other than young Binyomin Finkel. History doesn’t record the exact nature of his comments, but it was an early example of both the boy’s speaking ability and talent.

Rav Binyomin is noted for the sense of humor — inherited from his father — that is deployed at sheva brachos speeches and in his derashos. He shows a mastery of the standup comedian’s technique of exaggeration — selecting a theme, such as Erev Shabbos kitchen disasters, and drawing out its full potential in rapid-fire, droll sentences. What stands out, though, is his ability to captivate an audience without mockery or hurting others — generally the most basic tools in a comedian’s toolbox.

“It’s important to make people smile,” he says, explaining why humor is an integral part of teaching Torah. “Rav Moshe Cordovero says that chochmah needs to be dispensed along with rachamim — in the right dosage for the age and capabilities of the talmid. Like a baby needs its appropriate food, so too the Torah needs to be delivered in a way that the generation can accept it. Today, mussar needs to be interesting — it needs to be spiced with the right ingredients.”

The pidyon haben for baby Binyomin featured (bottom, from right) Rav Elyashiv, Rav Avrohom Elkanah Kahana Shapira, Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel. Standing (second right, to left) Rav Aryeh Finkel and grandfather Rav Shmuel Aharon Yudelevitch

First Among Equals

During those early days in Kamenitz cheder, another early accolade emerged: his lifelong nickname, “Binyomin HaTzaddik.” Rav Binyomin himself has attributed it to the fact that it’s a term used about the original Binyomin, son of Yaakov Avinu, and there’s a Tanna of that name mentioned in the Gemara Bava Basra. But family members say that the moniker seems to have emerged in school.

Later in life, Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz — an uncle who Rav Binyomin became very close to — used the term. “Can you call Binyomin for me?” he once asked a new bochur in the yeshivah. The bochur didn’t know who he was referring to, and the rosh yeshivah tried again. “Reb Aryeh’s son,” he clarified, to no effect, so he tried a third time. “I mean Binyomin HaTzaddik!” said Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz. That, the bochur understood.

The nickname was a sign of the regard of his peers for the young Binyomin Finkel. By the time he was a teen, the Kamenitz rosh yeshivah, Rav Osher Lichstein, was worried that his talmid was beginning to exhibit worryingly chassidic tendencies.

“Binyomin is becoming a Rebbe!” he told Rav Aryeh Finkel.

“What do you mean?” asked Rav Aryeh.

“Bochurim are coming to him with kvittlech before Shacharis to daven for them,” he explained.

Rav Aryeh’s response was interesting. “I’m not such a farbrenter Litvak myself,” he replied, signaling that he was comfortable with his son’s spiritual exploration.

The whole exchange was noteworthy, because Binyomin Finkel was indeed spending time in chassidic circles. The Beis Yisrael area that is home to Mir contains many varied yeshivos and communities. Next door is Meah Shearim, down the road are multiple chassidic courts and Sephardic yeshivos, and the Finkel bochur was an eager visitor in many.

One in particular drew his interest: Rav Yisrael Alter, known as the Beis Yisrael of Gur, was a magnetic personality who drew in many yeshivah bochurim.

“He was like a king surrounded by his bodyguard — there was an atmosphere of awe around him,” the Mashgiach remembers. “But he loved roshei yeshivah. He would come to observe the way that Rav Leizer Yudel and others conducted themselves. He was on fire himself, but he gave others extreme respect. And he was concerned that yeshivah bochurim keep high standards of kedushah, such as shemiras einayim.”

As a bochur, Binyomin Finkel began to attend the Beis Yisrael’s Seudah Shlishis tish, where he’d be asked whose grandson he was, and receive a piece of the Rebbe’s challah as shirayim. “I used to leave my own meal before bentshing, and continue there, but once I forgot and said Birkas Hamazon at home,” recalls Rav Binyomin. “The Rebbe looked at me, and strangely, departed from his normal custom. Instead of handing me a piece of challah, he said, ‘Did you not bentsh?’ ”

The relationship with the Beis Yisrael was substantial enough that the Rebbe suggested a shidduch for the grandson of the Mirrer Rosh Yeshivah. Rav Aryeh Finkel didn’t think that it was suitable, but checked with Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz, who said that they couldn’t ignore the Rebbe’s suggestion, and so the couple should meet.

Family folklore says that Rav Binyomin used a strategy that he would reuse in the future, when he felt that a shidduch wasn’t going to work but didn’t want to hurt the girl by saying so: he turned up for the meeting wearing a sweater backward, and the other side politely called things off.

Eventually, though, the sweater wasn’t needed when he met Minna Cohen of Givat Shaul. Rebbetzin Minna a”h, who passed way in 2016, raised a family of five sons and three daughters, as well as standing behind her husband’s public career as a mashgiach and maggid. She would wait up until the small hours of the night for him to return, knowing that he was public property and would go anywhere that he was asked to speak. She also became a magnet for baalos teshuvah, becoming their mother figure, marrying them off, and helping them through their births.

Heat Factor

Belzer composer Rabbi Yirmiyah Damen, whose own father was close to the Chazon Ish, and merited being called a “frumer chassid” by the latter, told one of Rav Binyomin’s sons that the same applied to his father. “He’s a chassidishe Litvak,” Damen said of the Mashgiach.

While his time in the chassidic courts nurtured Rav Binyomin’s innate warmth, the chassidic influences in his life didn’t lead to a change in externalities. Unlike others who donned a Gerrer spodik as a result of their closeness with the Beis Yisrael, Rav Binyomin was too rooted in his own world to change fundamentally.

“The basis for my derech hachayim was my father, who was one of the gedolei hador, and Mir,” Rav Binyomin says firmly. But he supped at different tables, systematically choosing to learn about different gedolim. He was close to the Lelover Rebbe, Rav Moshe Mordechai Biderman, the av beis din of the Eidah Hachareidis, Rav Dovid Yungreis, and Sephardi gedolim such as Rav Ben Tzion Abba Shaul, a neighbor of the Finkels.

“We loved to watch Chacham Ben Tzion coming out of Ohel Rachel, a nearby shul, after he gave his derashah,” recalls the Mashgiach. “I once ran to him to kiss his hand, but people around him said no, he only lets balabatim, not bnei Torah, kiss his hand. I said to them, ‘But I’m still a balabos!’ ”

The free hand that Rav Aryeh allowed his son in exploring different mesorahs stemmed from both wise chinuch and an awareness that his eldest was destined to seek out his own path. Later in life, Rav Aryeh went on to adopt hiddurim in halachah that Rav Binyomin had incorporated. And he took real pride in his son’s striking achievements.

“When I was learning in Brachfeld a few years ago, I told Saba that Abba was going to Rechovot for Shabbos, where he was going to give more than ten derashos,” recalls Reb Shmuel Aharon Finkel. ‘I don’t know how he does it,’ Rav Aryeh replied. ‘See what a rebbe my son has become!’ ”

The Mashgiach suits his message to the Mir’s varied audience, pausing after jokes to check whether the English speakers have understood

Hearts and Minds

The confidence that ultimately, Rav Binyomin Finkel was going to remain a Mirrer was rooted in his burgeoning relationship with Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz. Although Rav Aryeh had wanted his son to learn in Ponevezh — where the former had been among the first bochurim — Rav Binyomin was drawn to Mir by his great-uncle, one of the roshei yeshivah. After leaving Kamenitz at age 18 until he married at 23 years old, Rav Binyomin would be by Rav Chaim’s side almost constantly. Although Rav Nochum Partzovitz — Rav Chaim’s son-in-law and the Mir’s leading light when it came to lomdus — was the bochur’s maggid shiur for Gemara, his relationship with Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz ran far deeper.

At first sight, the two made an unlikely pair. Whatever the family relationship, there were deep differences. Rav Chaim was a classic Litvak, chumra-free, with only a single-minded dedication to Torah learning and mussar. Notions such as keeping the zeman of Rabbeinu Tam were foreign to him. With a growing dedication to various chumros (or as other disparagingly put it, “nerven” — halachic anxieties) Rav Binyomin seemed to be on a different path.

Yet it was their joint quest for regesh, the emotional feel for Torah and middos, that drew them together. “There’s something very unusual about how Rav Chaim has been perceived by history,” recalls Rav Binyomin. “He was a tremendous rosh yeshivah who has been remembered for his mussar.

“If you knew Rav Chaim, you realized that he was a gaon of both the heart and the mind, and of bein adam l’chaveiro. He demanded that a person act with respect for his friends, and he constantly emphasized the kavod a person needs to have for his wife. When he would talk of Rebbi Akiva’s wife and her mesirus nefesh, he would start to cry. When someone else was in trouble — whether he knew them or not — he would be visibly pained. ‘How would I feel if this were my son?’ he would say.”

Rav Binyomin constantly accompanied his great-uncle to simchahs. He was responsible for selling his seforim, and acted as the banker for the resulting fund. “Go to Benny,” the Rosh Yeshivah would tell his sons when they needed money, referring to Rav Binyomin with the name that he was widely known among the Finkel family.

He was the one who prepared the seforim that the Rosh Yeshivah needed for his shmuessen — and those talks were engraved on his mind.

One of Rav Chaim’s most famous teachings concerned the nature of bein adam l’chaveiro, the mitzvos that govern interpersonal relationships. Why is it, he asked, that Penina’s sons died because she pained Chana — as related in sefer Shmuel — when she did so only so that Chana should daven to have children herself? The answer, said the Rosh Yeshivah, is that a transgression of bein adam l’chaveiro is like fire; once it burns, it destroys everything in its path. To pain someone — even with the best motive — is literally playing with fire.

That message was absorbed deeply by his talmid, Rav Binyomin. It’s evident in his deeply human-centric approach to thinking about Chazal and Jewish history. “Think of Rebbi Akiva’s pain when his thousands of talmidim died,” he said with visible emotion in one shmuess. “Think what it is to sacrifice for so many years, to live in poverty, to leave one’s family, all for the sake of raising the next generation of Torah teachers — only to see your life’s work destroyed.”

Enduring Lessons

Commitment to Rav Chaim’s own life’s work around the study of mussar is the backbone of Rav Binyomin’s own day in the Mir. His multiple weekly shmuessen and seven weekly va’adim are classic mussar expositions, focusing on themes of Torah study, fear of Hashem, working on one’s middos and emunah.

So, too, his hours spent daily advising bochurim and avreichim in his office on the Mir’s ground floor are the classic duty of a Mashgiach as spiritual advisor.

There’s no surprise there, because despite the fact that mussar as a movement is over, its teachings, says Rav Binyomin, are as relevant as ever.

“Mussar’s foundation is cheshbon nefesh — keeping score of life’s balance sheet. Chazal talk of calculating the gain and loss in this world from doing an aveirah and a mitzvah.

“All of life is really a study in costs and benefits. Think of a man who has $10 million and wants to invest it in some stocks to make more. Someone who sees him giving away a million might say to himself, ‘Nebach! He’s lost it!’ But the reality is that he’s actually about to make even more money. The same is true of mitzvos — the time you devote to mitzvos looks like a loss, but we believe with total faith that Hashem will pay us back, so it’s really an eternal windfall. Stocks may fail, but who wouldn’t want such an investment?

“So, the outward form of mussar may have changed, but the core — which is learning to live with a real cheshbon — remains.”

“I have never seen a human being connect with such a wide variety of people.” Rabbi David Haber (left) introduced Rav Binyomin to the community of Deal, N.J.

Northern Lights

My first introduction to Rav Binyomin Finkel came almost 20 years ago, on a northward-bound coach as part of a bein hazmanim trip arranged by the Mir. As we made our way up the spine of the country, Rav Binyomin — sitting next to his oldest son — kept up a running commentary over the bus’s microphone about the history of the sites that we were passing. One point lodged itself in my mind for the next two decades. As we passed Har Tavor in the lower Galil, he remarked on the mountain’s mention in Hamavdil, the piyut sung on Motzaei Shabbos.

“This isn’t even the highest mountain in Eretz Yisrael,” he said, “so why does it say that ‘tzidkascha k’har tavor — our righteousness should be like Har Tavor?’ It should say that our merits should be like the Hermon!”

The answer, Rav Binyomin pointed out, had to do with the area’s topography. “Look at the surrounding region — it’s totally flat, and then the mountain suddenly rises up from the plain. And that’s what we’re saying — that our merits should, like Har Tavor, be very obvious.”

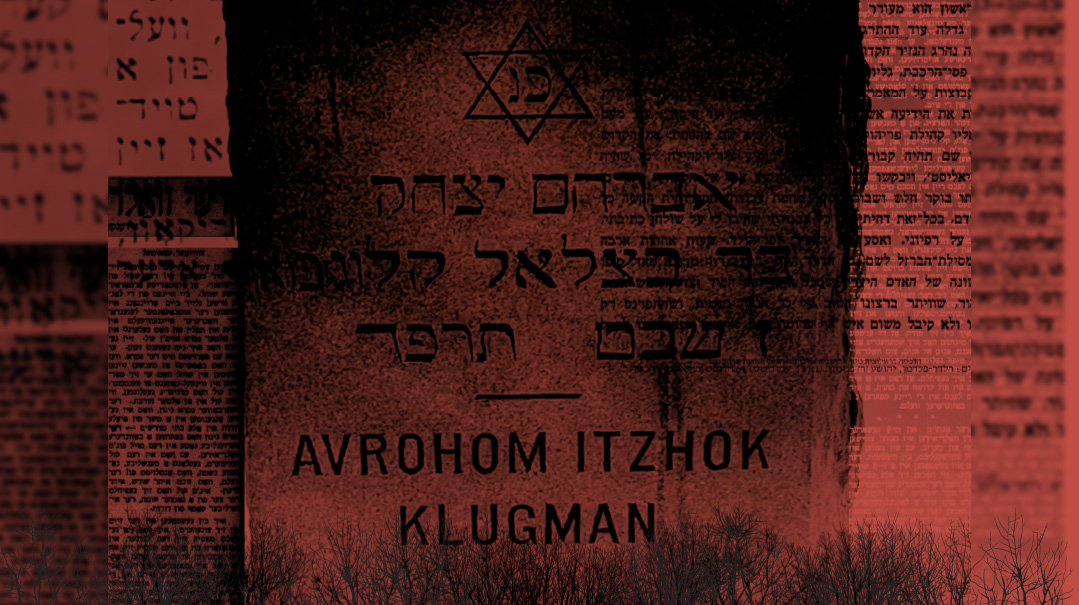

As it turns out, the explanation was one that Rav Aryeh Finkel was fond of sharing, and for good reason: the mountain and Kfar Tavor, the village built in 1901 on its slopes, were part of family history. They were the almost-home of the third formative influence of Rav Binyomin Finkel — his saintly grandfather Rav Shmuel Aharon Yudelevitch.

The Yudelevitch family history is that rarest of tales: a true story that is far stranger than fiction. It begins with Rav Shmuel Aharon’s grandfather and two brothers, three children who’d been orphaned of their father in Lithuania. In the horrifying poverty that prevailed, their mother remarried, but her second husband was too poor to feed the extra mouths of his wife’s older children. They were left with relatives, and then were left behind when their mother and stepfather moved to Eretz Yisrael in hope of a better future.

Desperately missing their mother, the heartsick little boys told their relatives that they were going to walk to Yerushalayim, which they innocently assumed was only a few days’ travel away. So the relatives — thinking that a good walk would do the boys some good — packed up a lunch and waved goodbye.

They never saw them again. Over the course of three years, the little boys — one as young as five years old — walked from Lithuania to Yerushalayim. Local communities along the way helped them with food, lodging, and transport. The reason was simple: with the Cantonist laws in force, orphaned little boys were ready prey for the shmad of the Russian army. It was deemed safer to send them on their treacherous way than allow them to face the certainty of the Tsar’s anti-Semitic draft.

What sounds like a fanciful legend is, according to the Yudelevitch family history, recounted in a book called In Every Generation, actually true. The hat of one of the boys, which was marked by a bullet fired by a guard at one illegal border crossing, is still in the possession of his descendants.

Word for the Wise

What’s noteworthy about the family’s fascinating story, though, is that Rav Binyomin is not that interested in it as history per se. He’s more interested in the epilogue, which involves Kfar Tavor, and his own grandfather’s epic decision not to go there as part of his personal growth.

“My grandfather, Rav Shmuel Aharon, was a holy man. It’s hard to quantify his geonus. He wrote one of the first seforim on electricity, was a baki in Shas and much else, and he was almost entirely a self-made man.”

That’s because once again, Yudelevitch family history repeated itself. When Shmuel Aharon was a young boy, his father died after being exiled by the Ottomans to Syria during the First World War. His widow remarried a man called Yosef Buchbinder, and they decided to leave Old Yerushalayim’s searing poverty behind for a better life in the moshav of Kfar Tavor far to the north.

Shmuel Aharon, though, decided to stay behind. “His stepfather was a good Jew, but my grandfather knew that a place like Kfar Tavor wouldn’t provide a chance to grow in Torah like Yerushalayim. So, he decided to stay behind despite the poverty he would face as an orphan. I have no idea what gave him the strength,” says Rav Binyomin.

Rav Aryeh Finkel’s first wife, Esther Gittel, who passed away in 1992, was a daughter of Rav Shmuel Aharon. That gave Rav Binyomin a close relationship with his grandfather, an extraordinary figure in the Yerushalmi scene. Young Binyomin used to accompany his zeide on long walks around what is now Ramat Eshkol, the border areas with Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem that were then unbuilt. Rav Shmuel Aharon walked for his health, which — like any other mitzvah — he was stringent about, and demanded the same from his daughter’s son.

One thing that a young Binyomin Finkel absorbed from his illustrious grandfather was the internal drive to grow. “Halomed Yeled,” says the mishnah in Avos, comparing a child’s learning to writing on fresh paper. “That means what one learns in a childlike state, with eagerness,” Rav Shmuel Aharon explained, “is retained much more easily.”

It’s a lesson that the Mashgiach himself often shares, quoting Rabbeinu Yonah that more than knowledge itself, the definition of chochmah is the love of wisdom and learning.

Among Rav Shmuel Aharon’s most enduring lessons, says his grandson, was that of kedushah, “In his own life he was extraordinary about protecting his eyes. Rav Aryeh Levin, who became his father-in-law, discovered that when he suggested the shidduch to my grandfather. After his parents had left for Kfar Tavor, the 12-year-old Shmuel Aharon had been taken in by Rav Aryeh Levin. He ate his meals in Rav Aryeh’s house; he had his bar mitzvah there, and he was part of the family. And then when Rav Aryeh suggested a shidduch with his oldest daughter Rasha, he was astonished by the reply.

“Chazal say that it’s forbidden for someone to marry a woman without seeing her,” he said, meaning that despite the years spent in his future wife’s house, he’d never once looked at her.

The Mashgiach himself stands out in this regard with an emphasis on shemiras einayim as the high road to ruchniyus. It may not be obvious, but he casts his eyes down when he’s in public and although he talks to female audiences, and women as well as men come to receive brachos, he’s very careful where he looks, maintaining his own standards while being careful to make the visitor feel comfortable.

That led to one incident that’s remembered with a chuckle in the Finkel family, when the Mashgiach’s own mother came to visit. Noting that the figure at the door was a woman, he smiled and gave the visitor a warm welcome. “I’ll just go and call my wife,” Rav Binyomin said – to the amusement of his own mother.

Ahead of a grueling schedule of vaadim and advice, morning seder in Mir’s main beis medrash is sacrosanct

Driving Lessons

Rav Shmuel Aharon’s legacy of chumra and hiddur is obvious as I join Rav Binyomin on another northward-bound trip — this time to Rechasim, a small town near Haifa.

Like the car itself, the Mashgiach is constantly on the move. From a shehakol on water, to Tefillas Haderech, the brachos are a major production — said with more concentration than the average person musters on Rosh Hashanah.

As the car flies up Route 6, he hands out bourekas and pastries like shirayim, but not before taking “Iber Maaser” — the stringent second round of terumah and maaser that followers of the Chazon Ish practice.

Our destination is Yeshivat Rechasim, a major Sephardi institution whose rosh yeshivah, Rav Eliyahu Tzion Sofer, was just niftar, and Rav Binyomin has been asked to say a hesped.

“Did you know him?” I ask.

“I met him once years ago,” he says.

“So have you thought what you’re going to say?” I ask.

The answer is a negative, and it stays that way for the rest of the journey as the Mashgiach is involved with answering different questions.

So it’s an eye-opener when Rav Binyomin stands in front of an audience of hundreds in Rechasim and starts to talk. Dropping into Sephardic pronunciation, and waving his hands in his distinctive way, he has transformed into a Maggid. He’s not telling stories, but focuses on a lesson from the navi about the challenges of Torah learning before Mashiach comes — and it keeps the audience spellbound.

“The Rosh Yeshivah had so many yissurim,” he says of Rav Sofer, who was sick for many years. “He had all the reason in the world to go easy on himself, but he didn’t. And that’s the message that I take from this, to remember that Hashem wants our avodah in every circumstance.”

It’s vintage Rav Binyomin Finkel. Not dazzling machshavah, but straight-up quotes from the Gemara or navi in their simplest form, and delivered with all the force of utter truth.

But there’s something else on the visitor’s mind that he wants to share with his audience: the war that has placed Hezbollah mere miles to the north, and the painful calls for the drafting of yeshivah bochurim.

It’s a subject that he’s addressed repeatedly in Mir over the last few months. “Here in the yeshivah we were raised by Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz,” he said on one occasion. “He had a pure heart, and whenever there was Jewish suffering, he cried terribly. Imagine how he would weep, seeing the suffering today?”

But as he repeats that message in Rechasim, he’s forced to address the controversy that has overtaken the unity at the beginning of the war.

“We know that Torah is the guarantor of Klal Yisrael’s survival, and so it’s nothing other than cruelty to the soldiers to demand that bochurim should stop learning. The vast majority of the Jewish people are good, and so the timing of this demand is only being fed by the incitement of a tiny minority.

“Unless you understand the crucial nature of Torah learning, you may not be able to understand why we won’t draft the bochurim, but I have one question for those who accuse us of sitting idly while our brothers fight. Do you think that the Chazon Ish had any less love for Klal Yisrael than anyone else? He loved the Jewish people, and yet he fought to protect the Torah learning of yeshivah bochurim.”

As he makes his way out of the yeshivah, a familiar sight plays out: the Mashgiach surrounded by 30 or so bochurim, each with a name for tefillah or a snatched question about how to enjoy learning or deal with a difficult home situation.

They lean eagerly into the car, and with a smile, Rav Binyomin answers each one patiently. He doesn’t allow the driver to leave until he’s sure that he’s satisfied all the customers, and only then can the window roll up.

Right Words

That almost superhuman patience vies with another character trait in the stakes for what defines Rav Binyomin Finkel: his uncanny ability to connect to Jews of literally any background. That was on full display last summer when he and his second wife, Rebbetzin Rochel, visited the Syrian community in Deal, New Jersey on behalf of the yeshivah. Over the course of 72 sleepless hours, he toured a dizzying array of the community’s shuls and spoke to groups and individuals of every type.

Rabbi David Haber, who is a rabbi of one of the local communities, escorted him on the whirlwind trip. “I have never seen a human being connect with such a wide variety of people, from the most to least religious, wealthiest to those on the other end of the scale, from senior rabbanim to those who haven’t seen a shul in years. He found the words for a shul where they didn’t understand his Hebrew. He found the right thing to say to a terminally ill woman and her husband. He talked to adults and children. Everyone was entranced.”

In a standout incident, the rav was introduced to a group of wealthy donors who happen to have financially supported President Trump. When they sat down together, one member of the group turned to him with a question: “What do you think of Trump?”

Given that the Mashgiach doubtless gives politics-as-entertainment a pass — and didn’t know of the group’s connection to the President — he might have been expected to come up short. But his answer indicated that he’d considered the issue as a mussar phenomenon.

“I’m grateful to President Trump,” he told the intrigued audience. “He’s older than I am, and yet when he was running for office he kept a 20-hour day. That tells me that if he can do it, I can do far more, too, for Hashem.” It was a genuinely insightful, authentic answer, with no hint of pandering to a group of wealthy men.

Besides the ability to connect with others, what impressed Rabbi Haber was something that is obvious after spending a day or two in the Mashgiach’s company — his serenity despite surviving on little sleep. “I never saw him agitated, I never saw him lose that smile,” he says.

On that same trip to America, the Mashgiach went to see Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky, who was then in a rehabilitation clinic after an illness. It was a Kamenetsky family yahrtzeit, and so those present wanted to make a minyan, but they came up one short. Eventually, someone procured a Jewish man who was at the same facility, and Maariv took place.

When he was about to leave, Rav Binyomin suddenly remembered something. “I forgot to wish the man a refuah sheleimah!” he exclaimed. Despite the fact that he hadn’t actually exchanged a word with the man, he walked back inside and insisted on tracking him down, so that he could wish a fellow Jew well.

Have you ever heard of ‘skiing’? People slide very fast down the mountain but they have some way to stop themselves from falling. And that’s what I learned from them – even if you’re falling, don’t let yourself slide all the way down”

Ski Lessons

The midnight oil is low in the lamp when Rav Binyomin Finkel finishes Maariv and heads out to his last engagement of the day — a group of talmidim from a few years back. For some reason, the alumni gathering takes place in the faded doctor’s office of Dr. Meshulam Hart, a well-known Bnei Brak physician. It’s not clear whether that explains the small electronic scales sitting on the table in front of the boxes of rugelach and bourekas, and which now serves to measure out quantities as Rav Binyomin takes maaser from the baked goods.

As he sits there with his talmidim, they’re both reverent and at ease with their rebbi. It’s a combination that reminds one of an old, stylized shtetl scene of a melamed with his beloved charges. So when the Mashgiach begins talking of himself as just another of the chaveirim, it comes across as genuine and unforced. Someone who talks so humbly with a child has no trouble conversing equally with a 16-year-old.

On the agenda is bein hazmanim, now days away. He draws a chuckle by saying that they need to help at home — and not just the fun bits. “Don’t say ‘Abba, Ima, I’m ready to help — as long as it’s just spraying water on the floor for my sisters to mop.’ ”

The Mashgiach is real with them. He discusses the long six-month winter zeman that suddenly started early due to the war, and acknowledges that it wasn’t an easy time. But then he urges them to stick to an ambitious learning program for their break. “Let’s learn Mishnayos Zevachim together — we’ll each have a daily seder in it, and then meet afterward.”

Last, he encourages them to avoid the pitfalls of bein hazmanim. That means being careful where a ben Torah goes, what he sees — and never to despair even if things go wrong. As ever, his message is based on a real-life encounter.

“I visited Switzerland last week on behalf of the yeshivah,” he says, “and someone took me to see the niflaos haBorei of the mountains.

“Have you ever heard of ‘skiing’?” he asks. “People slide very fast down the mountain— Oy! Ribbono Shel Olam! — but they have some way to stop themselves from falling. And that’s what I learned from them — even if you’re falling, don’t give in! Don’t let yourself slide all the way down.”

That, in a way, is the distilled essence of what draws people to Rav Binyomin Finkel. He’s a genuine tzaddik, who lives the excitement and elevation of avodas Hashem that he saw from his great forebears, and teaches it by example. His brachos are the same whether he’s standing in his place in the Mir, or catching a Maariv after an exhausting day on the road. His ability to smile and care about others is almost transcendent.

At the same time, he’s very much a tzaddik of our times, planted in a confused era, when a bochur can soar one day and feel like staying in bed the next.

That’s why he continues to go anywhere he’s needed: to uplift one more audience and relieve the worry of one more bochur.

That endless patience prompts me to share an observation with the Mashgiach, as the car pulls away from Itzkovitch and its stream of brachah-seekers, on that late Sunday night.

“I think you’re a baal mofes,” I say to Rav Binyomin. He laughs, and asks why. “Because after a long day, normal people get grumpy. Yet here you are, on an impossible schedule and you smile and have time for everyone.”

He smiles again, and looks out at the midnight streets of Bnei Brak while considering his words.

“How can I turn them away?” he says as the car picks up speed. “Each one is a ben yachid, and when he’s happy, it makes me happy, too.”

Coffee with Zeide

A

mong the pantheon of legends who surrounded Rav Binyomin Finkel during his childhood was his great-grandfather Rav Aryeh Levin. The Finkels lived some distance away, but the Mashgiach had warm memories of the tzaddik of Yerushalayim. “He lived in one room with a step in the middle of the room, with very few possessions, but a house full of true ahavas Yisrael,” says Rav Binyomin. “I remember him stroking my hand when I was very young.

“He was active almost until his last day (he was niftar in 1969, aged 84). One Shabbos my mother burned herself badly on the Shabbos urn, and immediately the next morning, he came to visit. It was quite a distance for him to travel.

“Another time, when I was about 10 or 11 years old, I went on my own to do a blood test. I was then in Kamenitz Cheder, which was near his house in Geula. When I’d finished, I went to visit my Zeide before returning to school.

“Rav Aryeh davened vasikin, so at about ten a.m. he sat learning. When he saw me, he said, ‘What are you doing here, why are you not in school?’ When I explained, he said, “A blood test? That’s hakazas dam — bloodletting. The Gemara says you need to have something to eat.’

“So, he made me a black coffee, which I drank, and with that kavod from my Zeide, I went happily back to learn.”

Second Sight

MY father doesn’t generally tell mofsim, miracle stories about gedolei Yisrael, with the exception of those that he knows to be true firsthand,” says Reb Shmuel Aryeh Finkel, Rav Binyomin’s son. “Two concern his grandmother’s second husband, Rav Chaim Sonnenfeld. “The first was about that zivug sheini between Rav Chaim Ze’ev Finkel’s mother-in-law Chaya’leh and Rav Sonnenfeld. After they’d met, the aged tzaddik asked for one more day to think it over, and then the next day he said that he wanted to go ahead.

Asked why he’d needed an extra day, his reply was chilling. ‘I needed to ask the first husband for permission to marry.’

“The second story took place a few years later. Rav Sonnenfeld turned to his wife and said, ‘You’ll live to the same age as me.’

“Indeed, that’s what happened. In 1962, 30 years after Rav Chaim Sonnenfeld was niftar at the age of 84, his wife Chaya’leh passed away at the same age.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1008)

Oops! We could not locate your form.