Flashback to Captivity

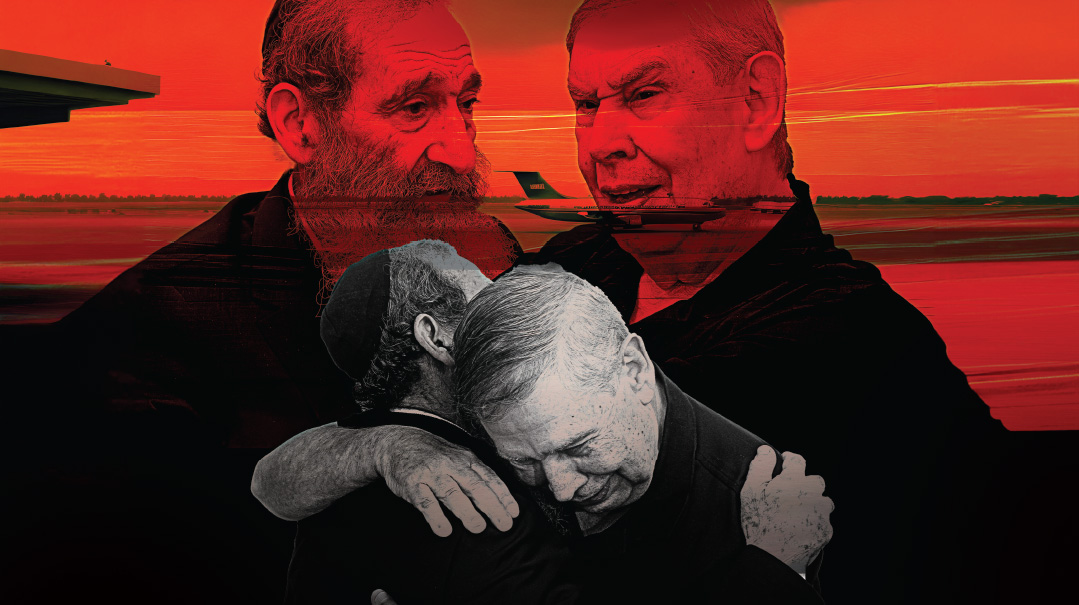

| April 30, 2024When Entebbe captive Rabbi Nachum Dahan met rescuer and former Mossad chief Tamir Pardo, the past and present converged into one dark tunnel

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Mishpacha archives

They look like they probably have little in common.

One is a French ben Torah from Bnei Brak named Rabbi Nachum Dahan, and the other is Tamir Pardo, former chief of the Israeli Mossad.

But close to 50 years ago, their paths indeed crossed in the heart of Africa, in a room filled with ruthless terrorists and petrified hostages. Pardo was a young communications officer for the elite Sayeret Matkal unit and mission leader Yoni Netanyahu’s radio operator during the famed Entebbe rescue in July of 1976; Dahan was a passenger on the hijacked Air France plane, held captive, tortured, and nearly killed by his captors until he and 100 others were spirited back to Eretz Yisrael by Pardo and his colleagues.

This is an emotional reunion, especially for Pardo. After the rescue planes returned to Israel, he’d had no personal contact with the hostages over the decades — he was soon afterward recruited by the Mossad and spent the next 30 years involved in secret international missions, until he was appointed to a five-year stint as director of the lauded spy agency in 2011.

There is a chilling current dimension to this encounter, as dozens of the 133 remaining Israeli captives — many no longer alive — have been languishing for months in the tunnels under Gaza. Somehow, the collective psyche of the nation is still fantasizing about another rescue — could Entebbe happen again in 2024?

“Since October 7, I’ve been feeling awful,” Rabbi Dahan says. “I find myself waking up at night from nightmares. I remember the brutality of my captors, and I only went through it for a week.”

Rabbi Dahan shares his story with Tamir Pardo, part of the rescue team to whom he owes his life. For Pardo, it’s a flashback to younger, more daring days when his team knew they had to move forward with the mission yet felt its success was a roll of the dice.

Nachum Dahan, brutally tortured by his terrorist interrogators, prayed for a miracle – and it came, in the form of IDF commandos crashing Entebbe in Idi Amin’s lookalike Mercedes

N

achum Dahan was born in Casablanca, Morocco, and came to Israel with his family as a child. But after several months of financial difficulty, the family left to France. Growing up in the 1960s, he followed a typical career track that included French army service, where he served as an officer in the medical corps. After his service, though, he took a detour and decided to visit Israel, staying for the next few years as a volunteer on Kibbutz Gadot, near the Syrian border.

He was there during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, with the battles raging close by and soldiers constantly stopping at the kibbutz to fill water trucks for the fighters at the front. One of those times, once the war had turned around to Israel’s advantage and the IDF was pushing toward Damascus, he asked to join them in order to document the war with his camera — and they agreed, as long as he put on a military vest so there wouldn’t be any questions at the checkpoints. Dahan documented such maneuvers as Syrian tanks being destroyed by the Israeli Air Force, and also made sure to have pictures of himself in an IDF uniform sitting inside an armored vehicle. Those photos, however, would put his life in very real danger.

In the summer of 1976, he decided to fly back to France to visit his family, and found a rock-bottom ticket for $200 on Air France.

“There were a lot of skyjackings at the time,” Rabbi Dahan remembers, “and I usually traveled El Al. I didn’t have a good feeling about this flight, but the price was right, so I booked it.” That feeling of dread increased when the plane made a refueling stop in Athens and let more passengers board.

And that was an invitation for a group of terrorists to board the plane.

The first leg of Air France Flight 139, headed from Tel Aviv to Paris on June 27, 1976, was uneventful. It took off as scheduled, carrying over 240 passengers and 12 crew members. But a few minutes after takeoff from Athens, terrorists from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and the pro-Palestinian German terror group Baader Meinhof pulled out guns and grenades and announced they were hijacking the plane.

Hearing screaming from the cabin, Captain Bacos initially thought there was a fire on board. The plane’s chief engineer opened the door to the pilot’s cabin and found himself facing a German terrorist holding a pistol and a grenade.

“If you stay still and do nothing suspicious, no one will be hurt,” the German told the crew. The terrorist pushed his gun into Captain Bacos’ neck and ordered him to turn the plane away from Paris and fly to Libya instead in order to refuel.

Captain Bacos flew to Benghazi, Libya, where the tyrant Muammar Gaddafi initially didn’t want to let the plane land because he wasn’t part of the terrorist plot. Only after the dictator got an official request from France did he allow the plane to land to refuel, and the crew was directed to take off once more and fly to Uganda.

The plane landed in Entebbe, where Idi Amin, Uganda’s ruthless dictator, was on the tarmac with a warm welcome for the hijackers. More Palestinian terrorists boarded the plane and 100 Ugandan troops were provided as well. The passengers were brought into the old terminal building that was no longer in use, where the terrorists examined papers and passports, separating the Jewish and non-Jewish passengers.

In total, 148 of the passengers were neither Jewish nor Israeli and they were freed and flown to Paris two days later, on June 29, 1976. For the 94 Jewish passengers — and 12 crew members who nobly decided to stay with the Jews even after being told they were free to leave (Captain Bacos told his crew they had a responsibility to stay with their passengers until the end, whatever that would be), a horrifying scenario awaited: The hijackers demanded the release of 54 maximum-security convicted Palestinian terrorists being held in prisons in Israel and around the world, as well as $5 million. If these demands were not met by the end of the week, the terrorists would begin executing the Jewish passengers.

M

onday morning dawned in Israel thousands of miles away, and with it came news of the hijacking. The security apparatus was tense. Arguments broke out about negotiating with the terrorists. At the same time, the army was considering a daring rescue operation. At the time, it sounded like a delusional fantasy. But as the days dragged on and the terrorists set one deadline after another for fulfilling their demands while the nations of the world stood by, it became increasingly clear that Israel would have to find a way to free the Jewish hostages hundreds of miles away surrounded by hostile nations, and do it alone.

Tamir Pardo, then 23 and a communications officer in Sayeret Matkal, recounts how his unit was called up for some kind of plan of action.

Representatives within the Israeli government initially debated over whether to concede or respond by force, as the hijackers had threatened to kill all of the 106 captives if the specified prisoners were not released and the funds not transferred. Acting on intelligence provided by the Mossad, the decision was made to have the Israeli military undertake a rescue operation, although the results were far from secure. It would mean flying 100 commando troops 2,500 miles through hostile airspace, neutralizing the terrorists and the Ugandans, finding the hostages, and whisking them back to Israel without being caught. From Prime Minister Rabin on down, many in command positions feared the operation would end in a bloodbath.

“So we started to plan,” Tamir Pardo remembers. “But how would we do it? The distance was huge, the IDF had never gone on such a distant mission, and with all our original thinking, how could we get four Hercules fighter jets from Tel Aviv to Entebbe, when we’d need at least one friendly country to refuel? We had to figure out how to exit the plane, get to the terminal, and free the hostages while catching the terrorists off guard.

“Like in the Holocaust, they separated the Jews from the non-Jews and sent the freed captives to Paris, which actually turned out to our advantage. The IDF and the Mossad flew to Paris to debrief them and garnered a lot of much-needed knowledge regarding the layout of the terminal, where the hostages were being held, how many terrorists were guarding them, how often they switched off shifts, and any other pieces of information that could help.

“We really had two missions: to take over the old terminal and free the hostages, and then clean out and neutralize the area where the Ugandan fighter jets were on the ground, so they couldn’t become airborne and chase us.”

Initiating the operation at nightfall on July 4, 1976, Israeli transport planes flew 100 commandos to Uganda for the rescue effort.

The Mossad had created an accurate picture of the whereabouts of the hostages, the number of hijackers, and the involvement of Ugandan troops, based on information from the released hostages in Paris. Furthermore, Israeli firms had been involved in construction projects all over Africa during the 1960s and 1970s, and one of those companies was Israel’s largest construction firm, Solel Boneh, that had actually built the terminal where the hostages were being held. That meant that while planning the operation, the IDF could create a replica of the terminal with the assistance of those who had helped build the original.

Furthermore, Pardo relates, the commander of the reserve force of Sayeret Matkal was Muki Betzer, who, a few years earlier, had been sent to Uganda to train Idi Amin’s own paratrooper brigade, and he was familiar with the territory.

M

eanwhile, Nachum Dahan was counting his own days of captivity.

“On the first day, Idi Amin visited. He said to us, ‘I’m taking care of you. You’re in good hands. Write a letter to your government telling them to exchange the hostages for terrorists.’ After the visit, trucks came for the first time to bring us food,” Rabbi Dahan relates.

On the third day, the Israeli hostages were separated from the foreigners. “The terrorists broke a hole in one of the walls of the terminal,” Rabbi Dahan recalls. “They said that anyone whose name was called should move into the next hall through the hole. They read out the names of the Israeli hostages. For the Holocaust survivors, this selection evoked memories of the horrible selections they had endured.”

Rav Dahan was surprised to hear his name called. He was French, and while he did have a temporary resident card, he didn’t have Israeli citizenship or an Israeli passport.

The captors didn’t believe him. They were sure he was hiding his Israeli passport somewhere. He was then hauled off to a side room — concrete all around except for a small window slat — for interrogation, where he faced the largest man he’d ever seen: a huge hulk with massive hands who picked him up like a sack of potatoes and threw him down on the concrete floor in a heap, beating him mercilessly.

His interrogators were convinced he was hiding something — maybe he was an Israeli spy? It wasn’t long before he discovered why they were so suspicious: They’d found the photos of his army escapades in his suitcase.

On Wednesday evening, three days before the rescue, Dahan was sure he’d be killed. A terrorist entered the room, loaded a pistol, and pressed it to his head. “What did you do in the Israeli army?” he demanded. Dahan told him that he was never in the army, but then remembered that he’d worked for a few months in the technical department of Israeli Aircraft Industries.

That answer satisfied the terrorist and he decided to release Dahan back to the passenger terminal. But not for long. On Thursday morning, a senior terrorist discovered that Dahan wasn’t in the isolated room, and dragged him back.

“The terrorist waved the picture of me on a tank in an IDF uniform,” Rabbi Dahan says.

“I told them it was just a picture he took for his friends back in France, but that just made the terrorists angrier. One of them took a stick and began to beat me so hard that the stick broke.”

At midnight on the night between Thursday and Friday, the deadline for the ultimatum the captors had given Israel expired. The Ugandans were in ecstasy after they heard reports that Israel would meet their demands.

Yet despite these reports, the terrorists didn’t let Dahan off the hook.

“The senior terrorist came in brandishing a pistol and after another long interrogation, I was sure he’d shoot me. At that point, I looked up at the crack of window that let in some sunlight, and I prayed to HaKadosh Baruch Hu for the first time in my life. It came from some deep place in my neshamah that I didn’t even know existed. I said, ‘Hashem, if You are planning to help me out of here, You’d better do it right now, because I’m not going to be able to survive this torture too much longer.’ It wasn’t long before I got my answer. A few minutes later, another terrorist came into the interrogation chamber and told me, ‘Get out of here. Go back to everyone else.’ ”

Rabbi Dahan says he did teshuvah on the spot. As soon as they arrived back in Israel, his first stop was a beit knesset.

Pardo listens to the account — he’d never heard this end of the story before. Yet while Dahan was being tortured, he and his Sayeret comrades were planning the rescue. But even just hours before the operation, Pardo was afraid that success would be elusive. “There were too many places where the operation could go wrong.”

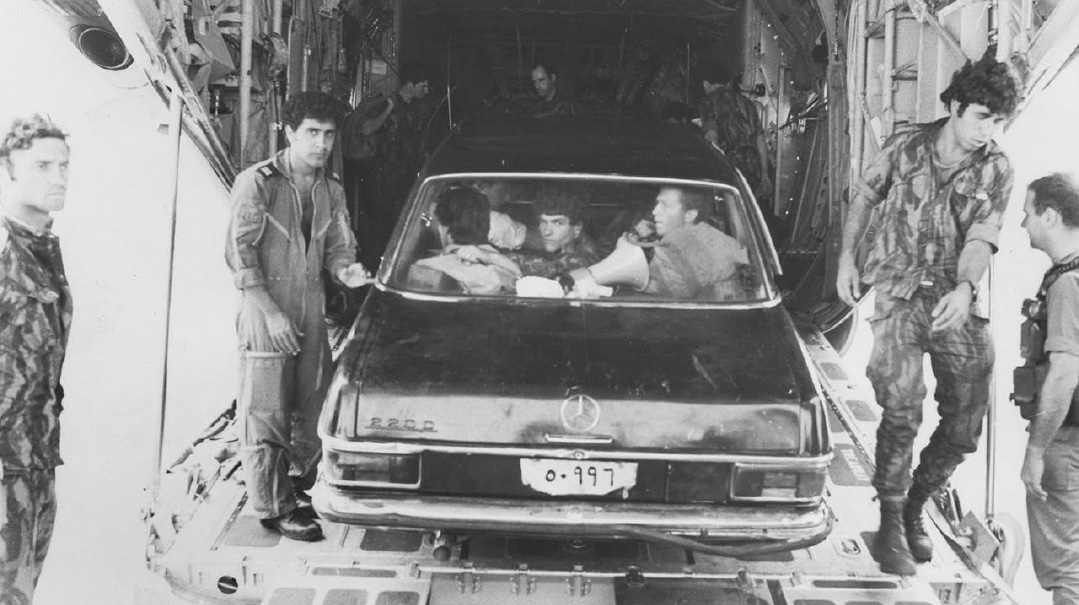

Still, it was approved on Friday morning. The units flew out from Tel Nof to Sharm-a-Sheikh in southern Sinai (which was still part of Israel, before it was given up to Egypt in the Camp David Accords). From there, four Hercules craft departed for Entebbe, flying low under the radar. The 100 soldiers in the four planes — which were transporting army jeeps and a black Mercedes — a double for Idi Amin’s car, which was to unload on the tarmac so that Ugandan soldiers would think the dictator had come back to check out the situation.

“We approached the airport,” says Pardo. “The plan was that it would be first illuminated, and then darkened right after we landed to prevent additional landings — which indeed happened. The job of the first force that landed was to light the runway for our incoming planes, and to neutralize the Ugandan air force so it couldn’t stop the Israeli Hercules planes. As we landed, I strapped the communications equipment onto my back and we got out onto the runway.”

The forces on the first plane unloaded their cars, including the Mercedes double. But at the entrance to the terminal, they encountered two Ugandan soldiers who realized something wasn’t right. Idi Amin had just recently switched his black Mercedes for a white Rolls Royce. A round of gunfire ensued, the Ugandan soldiers were felled, but the gunfire changed the plan.

“You touch down, you know you have just a few minutes,” Pardo says. “But we also knew that after the first shot, it would be chaos. It would be a matter of seconds until all the enemy forces would wake up, and meanwhile we had to traverse a few hundred meters until the terminal. There were shots all around, and a few minutes later, Yoni was shot. And from that moment on, we were on autopilot.

“As we were running,” says Pardo, who was Yoni Netanyahu’s radio operator, “I stayed close to Yoni. We came under fire from the tower, when a Ugandan soldier who was next to the terminal also opened fire at us. Yoni was hit… he was so close I could reach out and touch him. His body did half a turn and then he fell….”

The Israelis left their vehicles and ran toward the terminal. The hostages were in the main hall of the airport building, directly adjacent to the runway. Entering the terminal, the commandos shouted through a megaphone, “Stay down! Stay down! We are Israeli soldiers!”

The Sayeret Matkal force advanced toward the terminal and burst inside. “The soldiers were shooting in every direction, and anyone who wasn’t lying on the floor was shot,” Rabbi Dahan remembers. The terrorist at the door managed to put his finger on the trigger, but he was eliminated by an Israeli soldier in an instant.

One of the hostages, Pasco Cohen, stood up and was injured by Israeli fire. “I dragged him aside,” Rav Dahan says, “so he wouldn’t get any more bullets.”

A few minutes later, the Israeli soldiers called to the hostages and instructed them to board the Hercules plane that would leave for Israel. “They told all of us to head for the Hercules, but I stayed back with the soldiers. They said to me, ‘Since you’re here, tell us which of the dead here are ours.’ I pointed to a young man who had been killed and another badly wounded woman.”

Jean-Jacques Maimoni, a 19-year-old French immigrant to Israel, stood up and was killed when a soldier mistook him for a hijacker and fired at him. Another hostage, Pasco Cohen, 52, was also fatally wounded by gunfire from the commandos. A third hostage, 56-year-old Ida Borochovitch, a Russian Jew who had immigrated to Israel, was also killed by a hijacker in the crossfire.

In less than an hour, despite the three deaths and several more who were injured during the shooting, 102 hostages were rescued successfully. One elderly woman, Dora Bloch, had been taken to a hospital in Kampala and was murdered shortly after the rescue operation. Five Israeli fighters were wounded, but operation commander Yonatan Netanyau was Israel’s sole fatality of Operation Entebbe.

The Israeli commandos killed all the hijackers and 45 Ugandan soldiers, and destroyed 11 of Uganda’s MiG fighter planes.

“Looking back,” says Pardo, “we did what we had to. Although we carried out other rescue operations, over the years, the story of Entebbe is the one that gets the most acclaim. You couldn’t have written a more intense fiction drama.”

“They were the shlichim who saved our lives, plain and simple,” says Rabbi Dahan. “I remember moments when I thought I wouldn’t emerge alive from there. What I went through in that interrogation room left me inches from death. And for that, I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to Tamir and his friends, who risked their lives for us.”

N

early 50 years ago, Israel embarked on a brave — some might even say foolhardy — plan to rescue hostages in hostile territory far from home. Given all the mistakes that could have happened, it was surely a Divine hand that led to the awesome outcome. And so, our conversation comes back to the present. Today, there are also hostages. But this time, no one seems to have the ability to think in terms of Entebbe. (As of press time, 133 hostages are still in captivity —Ed.)

The comparison is the elephant in the room.

Pardo is the first to bring it up. “My son-in-law was a fighter in Naval Force 13,” he says. “He received a call from a good friend from Netiv Ha’asarah who was under fire that entire day. My son-in-law didn’t think twice. He got into his car, picked up a few friends, and set out for the south to help.”

But unfortunately, by the time he got there, there was no one to save. “He had already gotten the news from forces at the scene that this friend and his brother had been killed. When I heard that, thoughts of Entebbe flashed through my mind. And then, like now — the goal was to rescue hostages.”

Then, the incident ended within a few days, despite Entebbe’s distance from Israel. This time, with the hostages just a few miles away, there has been no success in releasing them. “Nearly fifty years ago,” Pardo says, “the State acted on its responsibility to its citizens and endangered hundreds of soldiers toward that end.”

He remembers an anecdote: “There was a conversation between Yoni Netanyahu, the commander of the force, and Motta Gur, the chief of general staff at the time. Motta said to him, ‘You understand that the chances of success for this operation are not one hundred percent. You may not have a place to land. You may not have enough fuel to get home.’

“And I can add that there were countless other risks. From the moment those four planes took off, Israel couldn’t save us anymore. And yet, the prime minister took this tremendous risk because he realized there was no other way to bring the hostages home. When we flew to Entebbe, we didn’t think for a minute whether we’d come back.”

It sounds like Pardo, who was chief of the Mossad from 2011 to 2016, is blaming Netanyahu (Yoni’s older brother) for not initiating another Entebbe-like rescue. But times are different, and Pardo himself would today probably never agree to such an operation. His operational style clashed with Netanyahu, and since leaving the Mossad, Pardo, a left-leaner, has been a scathing critic of the prime minister. (When Netanyahu appointed Yossi Cohen as Pardo’s replacement in 2016, he breathed easier. The connection between the prime minister and Yossi Cohen was warm and close and for Netanyahu, who didn’t see eye to eye with the defense establishment on Israel’s challenges, Cohen’s appointment was a relief.)

Of course, with hostages spread out across Gaza and Hamas itself claiming it only knows where about 40 of them are, another Entebbe rescue is practically impossible. But while Pardo — a vocal critic of Netanyahu even at the best of times — thinks the government should have done far more for the captives, Rabbi Dahan begs to differ.

“I’m on the other side of the story,” he says. “I know what it feels like to be a hostage. It’s dreadful. The torture, the lack of freedom, everything. And it’s true that we don’t really have a choice, and we have to bring them home. But how can we release murderers, baby killers?”

Pardo doesn’t agree. “Former minister Yizhar Shai said something a few days ago that I really admire. He said, ‘Yes, I’m prepared for even my son’s murderers to be released for the hostages. We can always kill or catch them, but a hostage who is killed or murdered can’t be brought back. The State acted on its responsibility to citizens during Entebbe nearly 50 years ago. It needs to do the same now. Remember, 19-year-old soldiers on the runway in Sharm-a-Sheikh. They knew they were flying with a significant risk of not coming home. All to save hostages? Why? To save lives.’ ”

The only problem is that Pardo’s own political cronies won’t authorize these very rescue operations because of the feared collateral damage.

For both Pardo — who advocates, at least publicly, to try for releasing the hostages at any price — and Rabbi Dahan, their personal Entebbe ordeal was a formative experience.

So much, that he remembers a discussion he had recently in the Knesset. “Every few years we Entebbe survivors meet,” Rabbi Dahan says. “At one of these gatherings, I met Dan Shomron, a former chief of staff who was the planner and one of the commanders of Operation Entebbe. He shook my hand, looked me in the eye and said, ‘You know, I’m not religious, but I can tell you something: I felt that Someone was helping us when we were in Entebbe. I felt the Presence.’

“I said to him, ‘Your neshamah felt the Presence of HaKadosh Baruch Hu.’ You see, Tamir, what you said — that Motta Gur told Yoni to take into account that there was no guarantee you would find a place to land — that’s important. Because there, we see the Yad Hashem. Here as well, we need to strengthen our emunah and believe that there’s Hashgachah and that everything is from Above.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1009)

Oops! We could not locate your form.