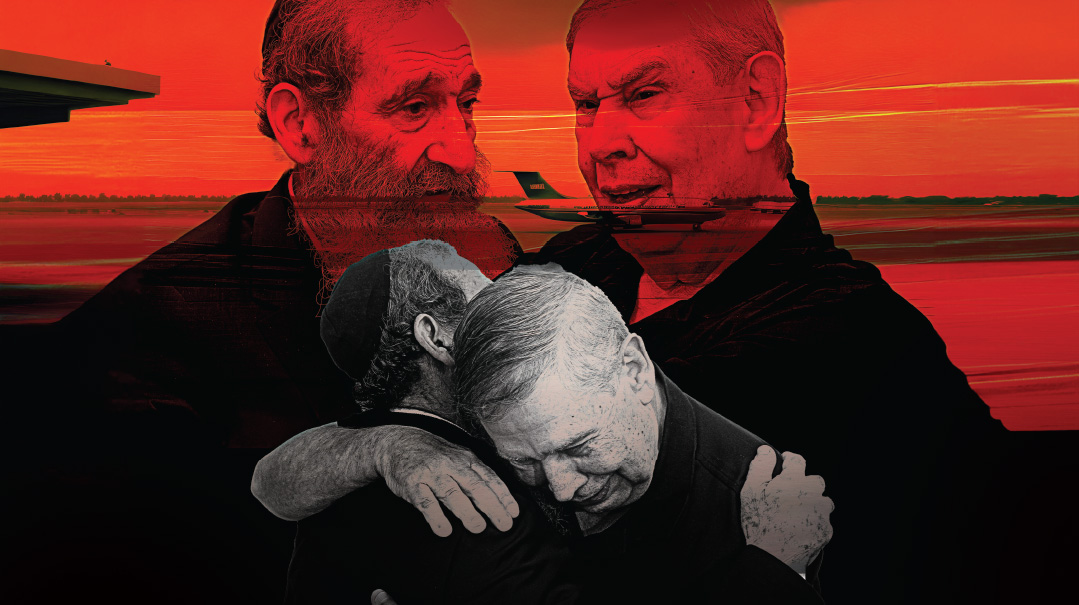

The Soldiers You’re Davening For

This war, more than ever, has given Jews around the world an attitude readjustment. Because those names, those lists we’re davening for, are us

Photos: Flash90

This week, thousands of families in Eretz Yisrael will have a missing place at their Shabbos table. Husbands, sons, brothers, sisters — nuclear families missing a piece of their picture as their loved ones have been called to the front. But while we tend to think of an invisible line between citizen and soldier, this war, more than ever, has given Jews around the world an attitude readjustment. Because those names, those lists we’re davening for, are us

This sunny Friday afternoon, the Landau home in Efrat has the frenetic feel of a day-care center. Plastic plates of Erev Shabbos kid-friendly chicken and rice cover the kitchen table, and several sets of energetic toddlers and babies belonging to married daughters and daughters-in-law vie for attention while an older sister valiantly organizes a playgroup outside on the steps. But this is no vacation kaytana at Savta’s house: It’s more like a companionship vigil. Bracha Landau’s five sons and two sons-in-law have all been called up to the front.

Suddenly there’s a buzz — Bracha’s son-in-law Yonatan, Chana’s husband, is on the phone and everyone jumps. Yonatan, who lives with Chana and their young family in the Negev town of Yerucham, is calling to wish good Shabbos. Hopefully there will be more phone calls from some of the others before candlelighting.

Bracha is the captain of this small empire, but today it feels like she’s steering a ship of uncertainty. She’s proud that the men of her family are serving the country they all love, but like any mother, she’s torn between the needs of her people and the tugging of her own heart.

Bracha, a computer programmer, and her husband Yitz Landau — a chemist for a pharmaceutical company — moved to Israel from Queens in 1992, first settling in Jerusalem’s Har Nof neighborhood and then moving to a large private home in Efrat. They lived through the Second Intifada, the Second Lebanon War, multiple military operations and countless terror attacks. Yet this time, Bracha says, the overwhelm is all-encompassing.

“On Simchas Torah morning, with all the air-raid sirens, we knew something serious was happening, although we were still pretty much in the dark,” Bracha relates. “But when I went home after shul and the phone rang a few times, I started getting nervous. The next time it rang, my daughter picked up, figuring it must be an emergency. ‘Hi, Chag Sameach. Where’s Menachem?’ It was my son Menachem’s friend. They were looking for him here, although he lives in one of the small yishuvim around Tekoa, not too far away. That’s how I realized they were rounding up the reservists. While only my youngest son is still in the army at this time and the rest are in various capacities in the reserves, at that moment I knew: Within a matter of hours all seven of my sons and sons-in-law would be called to battle.”

Bracha hasn’t slept much in the past week. She, like most people in the country, is glued to the news, searching, groping for some crumb of information that will make her feel calmer, help reduce the anxiety.

“Of course, I wish my sons would come home, but this is so much larger than our personal situation,” she says. “And as much as we want them home, we don’t really want that either. We mothers know what our sons have to do, and we also know at they’re incredibly motivated and they aren’t going anywhere. They love Am Yisrael. You look at the soldiers who come from the entire spectrum of Israeli society, some of them might have been marching in Tel Aviv and declared they wouldn’t serve in miluim while this government is in power, but today there is 130 percent response to the call-up. It’s everyone: the left, the right, the directionless — everyone’s in it together.”

Bracha knows she’s the one who sets the tone for the house, and that she needs to stay strong for her children and grandchildren. She won’t cry in front of them, but she says that in the past week, she’s broken down in the most random places.

“I went shopping for Shabbos this week, and I always buy what my kids like — until I realized that the men in my family would probably be eating rations sitting in their tanks. I had a breakdown right there in the supermarket.”

Bracha is part of a large extended family, and one of the cousins arranged a prayer get-together. “We were davening for the chayalim, and so I submitted my children’s names together with a brachah for the safety of all the chayalim. But then another cousin refused to list her own sons’ names. ‘We are davening for everyone. This is no longer a personal tefillah for ourselves, and not about my sons coming home,’ she announced, and all the cousins went along with her. I’ve been haunted by this all week: Did I do the wrong thing by submitting my children’s names? I still don’t know the answer.”

L

ike so many others, Bracha and her family members on the home front take chizuk and inspiration from the hundreds — maybe thousands — of clips circulating: of soldiers dancing before going off to the front, of officers and their charges singing songs of emunah and reciting Tehillim and Tefillas Haderech, of truckloads of army-green tzitzis being shipped off to the battlefield. (Today there’s not a pair of tzitzis to be found in any store — they’ve all been bought out, with tens of thousands on order and bochurim in shuls and batei medrash taking piles and piles and tying one pair after another.)

Some of those clips feature Arky (Aharon) Staiman, a young American-Israeli and father of three who is a popular tour guide during peacetime (rated Jerusalem’s top guide by Tripadvisor), and who, now that he’s been called up to the army, decided to use his connector charm to inspire and strengthen others during these tough days.

“There’s so much fear going around, so many bad videos, I want you to be someone’s light for the next few hours, do something good for someone else, take a mitzvah that you haven’t done in a while, be kind to someone, smile — this is what Am Yisrael needs…” he tells his viewers from the cockpit of a helicopter as he’s about to descend on a mission. Arky’s unit is the military equivalent of ZAKA, whose job is to collect bodies, body parts and blood — but to do so on the battlefield while under fire.

Arky’s father, Jeremy Staiman, has been helping his son get those clips disseminated, and that’s therapeutic for him as well. “We’re very idealistic people, we came on aliyah from Baltimore in 2010, and we’re really proud of what Arky’s been doing, but I’ll be the first to admit that when it’s your child in the war zone, all of a sudden it becomes a different story.

“There’s a lot of crying, a lot of fear, a lot of not sleeping, a certain natural, fleeting, knee-jerk reaction that wait, a hundred soldiers have been killed, maybe this is a mistake, I wish my son wasn’t called up. But then you just strengthen yourself and realize we’re all in it together. I think I can speak for most parents in this situation — we’re all walking around like zombies, unable to focus, in a fog.”

Staiman, owner of Staiman Design, a graphic and web service provider, lives in Ramat Beit Shemesh with his wife Chana, an ultrasound technologist. While his main profession is in graphic design, he’s also a bit of a composer. In order to give some parnassah to musicians during Covid, Staiman and vintage vocalist Motty Kornfeld (they’ve been friends since making a record together in 1980) produced an album of 80s-style Jewish music, combining talent from that era and some of his own compositions with today’s best musicians.

Now, though, Staiman is playing another track.

“My mother was a member of the chevra kaddisha until she was 80 years old, so what Arky is doing is really part of our family upbringing,” Staiman says. “Arky is part of the chevra kaddisha of the army, and it’s the highest calling, the holiest work. I can feel the nachas of my parents from above. But the tales from Kfar Azza where he’s been stationed are too horrific to even mention, just unspeakable. We worry that he should be mentally healthy coming out of all of this.”

Jeremy and Chana are fortunate that not only do they get phone calls, they’ve had several opportunities to visit with their son over the past week, when his team gets a few hours of respite from their gruesome tasks.

Arky is a communicator, says his father, and for his own therapeutic journey, he makes long audio clips describing in every tiny detail what he’s been through.

“This is how he’s processing all the horror he’s been exposed to,” says Staiman. “He told us, ‘Ima, Abba, I’m doing this for myself. You don’t have to listen to it.’ I did listen a little, and it was a huge trauma for all of us. I have an old friend who davens in my shul and was a US military chaplain for 33 years. We’re scheduling a meeting with him this week, to help our neighbors and friends process all the horrifying details.”

While we’ve all heard sketchy descriptions of the Hamas-perpetrated atrocities, many of us don’t have the stomach to hear it all.

But Chana does. “I listened to every minute of it, because I wanted to experience what my son experienced. A mother wants to feel what her child is going through,” she says. “I wanted to be there for him, to be able to understand what he went through and what he had to face. I feel like it’s my way of being in solidarity with him, and with the murdered people he was tending to. I wanted to feel what they went through — maybe because my father was a Holocaust survivor. I heard those stories from my father, what they did to him and to his family members that were murdered.”

Arky’s not in direct combat now, but he is trained as a paratrooper, and it was after the Second Lebanon War that the IDF realized the need to train soldiers to rescue bodies under fire. He’s been trained to get bodies out of the killing field under fire, so the government can know — are they dealing with a body, or with a kidnapping? An agunah or an almanah?

“He wasn’t really trained to do what he’s doing now, searching for bodies and taking them out of homes and out of trenches, out of closets and out from under beds, putting themselves in the victims’ position and envisioning where they would try to hide,” says Staiman. “And some of those houses are still booby-trapped. Is he in the same mortal danger of combat soldiers going after terrorists? Probably not, but he’s right behind them.”

There has never been as detailed coverage of a war zone as there is today, with soldiers themselves posting clips before they hit the front and their phones are taken away. It makes all of us realize, more than ever, how Israeli society isn’t divided up between citizens and soldiers. Those chayalim — offering up prayers, finding time to learn daf yomi, even putting on tzitzis for the first time — are all of us.

“You can hear people davening for the amud and know what’s on their mind,” Staiman says. “For example, there are so many references to ‘shalom.’ In our shul, when the Kohein’s voice cracked as he uttered those words, I knew what was in his mind. We can all pick out a few words — someich noflim, rofeh cholim, mechayeh meisim — and contemplate how relevant they are to all of us. Because our soldiers are sons, fathers, people who have chavrusas, just like the rest of us.”

P

arents find all sorts of ways of coping when their children are on the front, and there’s probably no better way than throwing oneself into chesed for the soldiers. Ilanit Melchior, a mover and shaker within the Jerusalem hi-tech and tourist industry, having served for over a decade as head of tourism development, is now rolling up her sleeves in an industrial soup kitchen in Netivot. In the last week, she and her team have been busy providing over 2,000 meals a day for soldiers, as a warm, homey alternative to cold field rations.

For Ilanit, a daughter-in-law of Copenhagen’s former Chief Rabbi Binyamin Melchior, it’s a way to shift out of the natural maternal anxiety over a son serving in a commando unit in the north, and another son who was in a study program at Kibbutz Nachal Oz, one of the Gaza border communities overrun by terrorists (the group happened to be home for that Simchas Torah/Shabbos).

“I knew I couldn’t just sit around watching the news and waiting,” Ilanit says. “I knew we had to do something constructive, when a contact of mine told me, ‘You know, I have a huge kitchen in Netivot.’ I told him, ‘Nu, let’s get to work – I’ll organize everything.’ We got a lot of volunteers, many chareidim who were happy to do their part in the war effort, but some people were telling me, ‘Why bother with food? The army has enough food.’ But we all know what it means to eat manot krav three times a day. We want to give warm, homemade food to nourish their hearts as well.

“Today I’m in touch with hundreds of mothers, soldiers, officers, so many people who’ve gotten on board. Just this week the Rami Levy supermarket chain donated vegetables, and many contacts from around the world are sending money in order to do their part. And it keeps me busy too, keeps me in the loop, feeding our soldiers and giving them a little taste of home. For them, it’s more than the food, it’s a sign that they know we’re thinking of them.”

Ilanit is especially gratified by the little microcosm of society she’s created around the kitchen. “There are so many types of volunteers – secular, chareidi, everything in between, and they’ve all come together to do their part in defending our country,” she says.

Ilanit is a powerful, influential woman with a lot of clout. But when it comes to a son on the front, it doesn’t really matter who you are. “We’re all just mothers and we’re all in it together,” she says.

A friend of hers told her, “Ilanit, what’s the anxiety? Your son is in the north – he’s safe.” Ilanit wouldn’t hear of it. “No,” she told her friend. “Every soldier is a son of all of us.”

Asahel Merucham of Tel Aviv says he wishes he could find some of that positivity within himself, but he never learned the language of prayer and emunah.

“My son Iddo is now serving in the reserves near Gaza, and we spend most of the day worrying about him, because he can only call or message us occasionally,” Merucham says. “The soldiers don’t have very much battery on their phones, and when they go on missions, they have to leave the phones behind. Since we know approximately where he is, we scrounge for information in the media about what’s happening there, and then try to imagine what he’s going through. As soon as we read that there was a firefight there, we fear that he was caught up in it.

“This whole war has forced on us a state of constant anxiety,” Merucham continues. “Our children are exposed to things that will affect them for a long time. Iddo’s best friend – who was studying medicine – is a reserve officer in the transport corps. He’s been transporting bodies for burial for days, and yesterday he fell apart and was sent home with PTSD.”

E

sther Gur, a former civil engineer who today teaches self-empowerment and applied chassidus, has a motto that she says keeps her equilibrium in balance, even as her Chabad chassidic son-in-law is on the front and her only daughter (she has several sons) and baby moved in with her.

Esther, who is no stranger to tragedy and challenge after losing her husband last year following years of debilitating illness, says there are two possible reactions when something huge, confusing or horrifying happens. The first approach is to try to make sense of what happened, and in the process to just talk and talk and talk about it, obsess about it and turn it around and around. But because what’s going on is so beyond our comprehension, because Hashem is infinite and we are finite, in our futile attempt to understand, we actually become dysfunctional.

The second option, the way to keep balanced, is that right at the outset, I acknowledge that this is bigger than me, and I’m not even going to try to understand it. “I have a job to do,” she tells herself, “and I have to keep doing my job and not get derailed by all the confusion, which I’ll anyway never understand.”

Both Esther and her daughter Chana Mindel are of one mind: that worrying isn’t going to help. “Yisrael,” says Esther of her son-in-law, “is in the best Hands.”

Chana Mindel, for her part, has an entire seudas hodayah prepared in the freezer, for the minute her husband walks through the door.

“We have to reframe our assumptions,” says Esther, the same line she shares with her students. “Why do we want to live in a place of pachad and anxiety? We can take a different approach. It doesn’t mean terrible things aren’t happening, that there is a huge tzarah going on, but each of us has a job to do in this world — so who has time for fear? A woman in shul screamed at me last week, told me I’m unfeeling, insensitive and apathetic. I think it’s more that I don’t flaunt my pain. There’s always room to worry, if you want to live your life that way, and there’s always a place to live moment by moment and not be paralyzed by fear, to show up for live and move through whatever Hashem puts in our path. As much as humanly possible, I’ve trained myself to focus on the second option. Where else should I be?”

T

hat pretty much sums up Leah Lewin’s approach to life’s challenges as well. She’s a teacher at Baer Miriam and other seminaries, a musician and composer, and a longtime resident of Jerusalem’s Sanhedria Murchevet (after stops in Har Nof and Beitar) and the neighborhood’s Anglo community under the leadership of Rav Yitzchok Berkovits. She’s also been challenged with a son who has severe special needs, and two children struggling with their Yiddishkeit. Her son Moshe, 19, is now serving in a tank unit in the north, under threat of a Hezbollah attack.

“We didn’t send Moshe to the army,” says Leah, whose husband Rabbi Yehoshua is a rebbi at Aish HaTorah. “And although it’s not exactly our family’s derech, it’s just overwhelming how the entire community has embraced him and is davening for him. I’ve posted a lot about our family over the last three years in our neighborhood email group, and the neighborhood still considers him one of ‘our children,’ from ‘our community.’ Even though he doesn’t look like them today, they still consider him one of theirs.”

Maybe it’s partly because Moshe, with his golden hands, would corner the market before Succos on koisheklach, the woven holders for the arba minim. His were genuine works of art, with his signature ring at the top of the lulav a stunning woven crown — everyone in the neighborhood wanted a Moshe Lewin koishekel.

While Moshe has spent the last three years searching for his own way, he never totally separated from the community. He would go to shul on Friday night, and was still helping out with the treats last Leil Shavuos, a job he’d had since he was one of the “older kids.”

“He still has his attachment to the community, and I give tremendous credit to the community, who are with him on the journey to healing,” says Leah. “He chose the army as his next step — and although it’s not something we would choose for our children, we’re with him as he’s sitting in a tank somewhere up north, so brave and motivated, yet, as he revealed to his older brother, so terrified.”

Moshe and his comrades were holed up inside that tank for six days straight, finally let out on Friday to get cleaned up, shower and call home. “Mommy,” he told Leah half-jokingly over the phone, “we really just wanted to see some action.” To which his older brother replied, “Moshe, between all of Mommy’s tefillos and the nonstop davening of the community, you’re not going to see any action….”

Moshe, says his mother, is still too young to understand how all the pain he went through since age 15 generated an equal amount of light. “There’s been a tremendous acceptance and reframing within the community,” says Leah. “One day, I hope to tell him how he helped Klal Yisrael grow in ways they wouldn’t have been able to, and specifically now, during the war, everyone has taken on so many precious kabbalos. I’m in awe of some of these young women — I’m a facilitator of a young women’s group, and am just amazed at how they’ve risen up and taken on so many mitzvos and so many collections. They are totally committed to helping bear the burden.”

Last Friday, when Leah sent out to her community the message, “Moshe ben Leah Shoshana wishes you a good Shabbos,” so many responded, “He’s our Moshe!”

Most Anglo-born mothers with children on the front knew it could happen from the time they made aliyah and moved to communities like Efrat or Beit Shemesh or Nof Ayalon or the dozens of other hospitable enclaves. But it was something Leah and her husband did not expect.

“Look,” she says, “we need the guys on the front, and we need the guys in yeshivah learning who have their back. You know, when we think about Israeli soldiers, we automatically think of combat soldiers and fighter pilots. But really, for every soldier on the front — and it’s really hard to get into those combat units — there are eight soldiers behind him who are taking care of the machsanim, the supplies, the inventory, peeling potatoes in the kitchens, doing the paperwork.

“Moshe so wanted to be in an elite unit. He did not want to be peeling potatoes in a kitchen in Be’er Sheva. So he did combat training for eight months before he even enlisted — that’s Moshe, he’s a masmid in whatever he does. In his last year in yeshivah, he learned hundreds of blatt Gemara to ‘buy’ chassan Bereishis. And he’s also taking that with him into his tank.”

Leah says that as the mother of a child who’s struggling, there’s always that consideration, that weighing of how much to push and how much to hold back. “I wasn’t sure if I should give him a sefer Tehillim when he enlisted, and I never told him, ‘Just say one brachah a day’ — all that is between him and Hashem. But on Yom Kippur, one guy brought a machzor to the unit, and Moshe sang every tefillah that has a niggun. ‘Ma, we just sang the whole thing,’ he told me. He probably had the most meaningful Yom Kippur of his life sitting in a tank near the Lebanese border.”

Leah admits that for her, the army issue was never black and white. “My father, who passed away three years ago, served in the US armed forces for over 50 years,” she says. “He was in the medical corps, so I grew up surrounded by army. It was his greatest pride to serve in the armed forces, so we’ve always had respect for army personnel, and I think my family senses that.

“True, there are many chareidi families today with kids in the army and it doesn’t really matter how they got there — either they went to ‘Nachal chareidi’ because they didn’t find their place in yeshivah, or they’re struggling with their Yiddishkeit to one extent or another, but at the end of the day we’re all united. I’ve learned that there are no longer any judgments. For me, it might not have been my l’chatchila, but it is my metzius, and I’ve gotten so much support from within the community. Because it’s not about ideology. It’s about love and soul connection.”

With reporting by Gedalia Guttentag

The Real Us

YISHAI SLUTZKY is a sixth-grade rebbi in Ramat Beit Shemesh, currently stationed on the Gaza periphery

Because I speak English, I’ve been talking to journalists from international media organizations. I’ll never forget the horrors I saw, nor the stench of death, in the area around Gaza, and as I described some of these sights — which I won’t share with readers because they are so painful — some of those journalists were brought to tears. I took them to the home of a couple who had desperately attempted to hide their twin babies in a cupboard piled with blankets as the Hamas gunmen approached. The babies were found — alive — hours later by soldiers, while their parents lay dead.

Over the last few days, we’ve been accompanying families back to the destroyed homes of their loved ones. In one, a grandmother wanted to rescue the two goldfish that were the only remnant of her once large family’s possessions. Her children and grandchildren were gone — all that remained were the two fish. We retrieved them for her, and then they died.

My unit is mixed secular and religious and many of the men in my platoon were at the anti-justice reform protests, which means that we were on opposite sides politically. Months ago, seeing the incredible divisions and hatred fostered by the opposition to the justice reform controversy, I said to my wife, “Only Hamas or Hezbollah will save us from this division.” Those divisions have now melted away. Some of the secular members of the unit said to me, “Yes, Yishai, we’re together — but that will only last as long as the war. Then, we’ll go back to being divided.”

But I said to them, “No, you’re wrong — what we’re seeing now, this is the real ‘us.’” Because if the divisions were real, why would we all be volunteering to return and serve in such high numbers to defend people who we’re estranged from?

And inside the unit, with all the shock of being part of an army that was mauled in this way, there’s a sense of clarity and determination: Our commanding officer told us, “If we win a smashing, clear victory — not like the recent indecisive rounds of fighting — then our children will live here in peace.”

Short Friday

By Yonatan Slutzky

Guard duty with Yaakov, six a.m. to nine a.m. We alternate between conversation and silence. Suddenly, we realize that it’s Erev Shabbos.

It’s not just the approach of Shabbos that hits so deep, but rather the fact that it’s Friday right now — and a week has gone by, the next unit of time after a day. Existence is no longer a bleary succession of days. Days are ranging themselves neatly into weeks and the first week has come and gone.

We’re all outside our comfort zone, in uncertainty and fear for the families we left behind. The scenes from last Shabbos don’t help. But at the end of the day, despite the resentment and the nerves, there’s a sense of shared purpose and destiny, a profound comradery that brings us all together and guarantees our victory. Some moments are harder than others, it isn’t always rosy, but by week’s end, we’ve all got our eyes on the job — as long as it takes, whatever it takes. We’ve been rallied to the flag — but that doesn’t mean there’s no fear. After all, we had to report for duty out of the blue.

It’s Friday today. We should all be engaged in Shabbos preparations — shopping, cooking, cleaning. But because of the concentrated evil that overflowed this week, we’re preparing for combat, tending to missing equipment and the halachic aspects of this strange new Shabbos coming up. Instead of singing Shabbos songs in the kitchen, some of the guys are strumming a guitar outside to keep our spirits up. After the poisonous evil released into the atmosphere this week, we’re here to purify the air and bring back hope. And the guitar strumming to Shabbos tunes is part of that. In the same place that one week ago was teeming with the servants of pure evil, shouting what they shouted and doing what they did, soldiers are sitting and strumming a guitar, talking about life and what we’ll do at the platoon barbecue after the war.

The only thing that’s clear is that we’re here to drive away the terrible darkness that was left here, and with G-d’s help, we’ll not only drive it away but replace it with a great light.

Moment to Moment

RABBI ZACH FRISCH, originally from Florida, has been in Yeshivat Shaalvim for the past 12 years, first as a Hesder student, and later as an avreich and then a rebbi. He lives in Shaalvim with his wife and children

On Simchas Torah morning, as we were davening, we started hearing the bombs, and then came the rumors of people being killed and kidnapped. So I went home to check my phone, and I saw that my commander had told me to prepare a bag and be ready to go because we’re going to be called up for the war. I went back to shul to finish davening, and as I was holding my children under the tallis during Kol Hane’arim, my phone went off in front of the entire yeshivah.

The Rosh Yeshivah gave me a brachah, and the yeshivah boys were very distraught but also very proud. Over the next few days, we had been doing exercises to prepare for combat, making sure that our game was up to par. We started protecting towns in the north near the northern border. Can’t get into details, of course.

Because I have so many American students and friends, I feel responsible to keep them up to date with what I’m going through and what the soldiers are going through. One thing we’ve been speaking about a lot is how to live with uncertainty — when will be the next time we can go home and see our families? I try to check in at home a few times a day.

We have time to daven, baruch Hashem — three times a day with a minyan. And knowing that the people behind us have us in mind with their tefillos and Tehillim is so helpful. It boosts our morale when we’re getting all these donations of food and people are buying us dinner and gear. It makes us feel connected in a very, very strong way. Do we really need so much Bissli? The truth is no, but it’s very important that they feel that they’re giving toward something.

In preparing for battle, you have to access your emunah reserves. Emunah doesn’t mean that you believe that everything will be good. It means that you believe that whatever Hashem’s plan is, whatever is going to happen, is all siyata d’Shmaya. At a certain point, you learn not only to live with uncertainty, but even to embrace it, to live moment to moment with HaKadosh Baruch Hu.

Still, there are moments when you’re really scared, you’re moving and you don’t know where you’re going — in the last six or seven days, we’ve been in six or seven locations. And almost like Am Yisrael in the Midbar, they didn’t know if they were going to encamp for ten years or one day.

There’s definitely talk among the soldiers, but basically, we know as much as you guys know in terms of the news. And yes, there are questions, and those questions will be asked after this war is over, after people stop dying. Someone’s going to have to give din v’cheshbon on that, but it’s not really what we’re thinking about now. Now we’re focused on the mission.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 982)

Oops! We could not locate your form.