Setting the Record Straight

| August 22, 2023“Jewish history as a discipline and Jewish history books in general did not come into vogue until the late nineteenth century”

Title: Setting the Record Straight

Location: London

Document: The Sentinel

Time: 1924

It has truly been noted that history is too important to be left to the historians. This is certainly true in the case of Jewish history. Jewish history as a discipline and Jewish history books in general did not come into vogue until the late nineteenth century. Jewish historiography, therefore, has been almost exclusively the product of secular Jews (the main exception being the fourteen-volume series on Jewish history by Ze’ev Yavetz, first published in the 1890s), who held a strong bias against rabbinical Torah Judaism. Thus, the irony of most Jewish history texts is that they have been written with condescension, if not hostility, to the basic beliefs and true heroes of Jewry over the centuries.

—Rabbi Berel Wein, introduction to Triumph of Survival: The Story of the Jews in the Modern Era 1650–1995

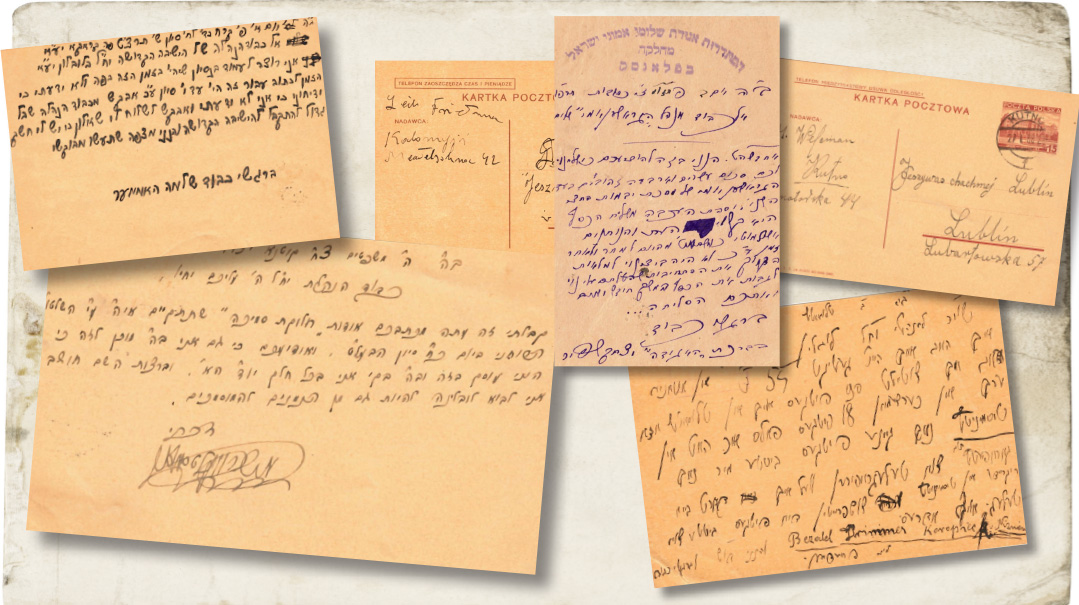

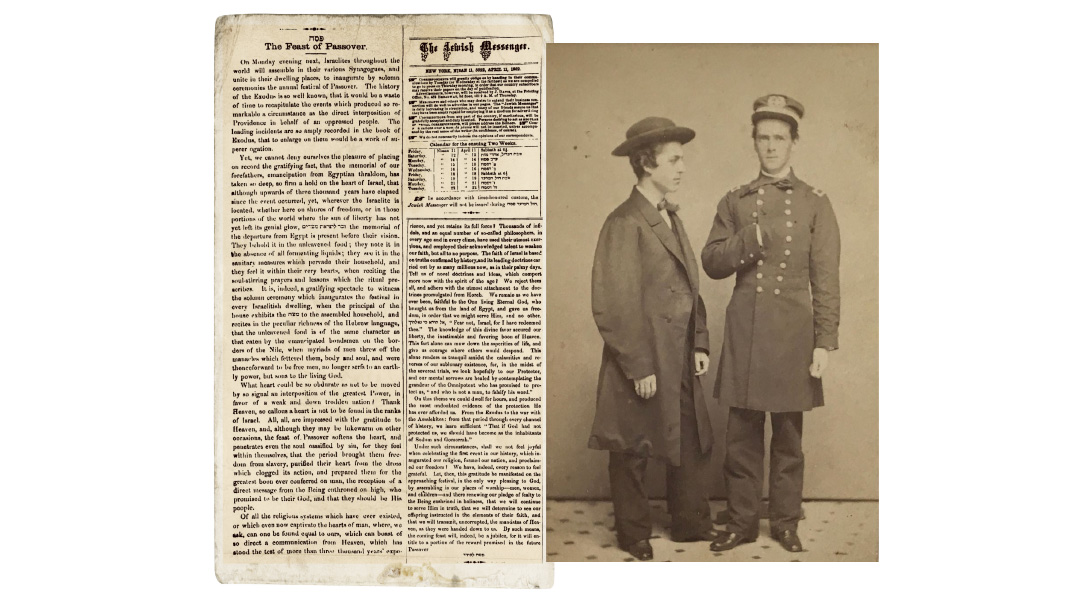

Jewish historiography experienced a rebirth in the modern era. The Wissenschaft des Judentums (“science of Judaism”) movement in 19th-century Germany was the first to generate modern interest in researching Jewish history. This culminated in the 11-volume work of Heinrich Graetz (1817–1891) entitled History of the Jews. Though it achieved renown in academic circles, it received considerable criticism in religious circles for its nontraditional approach and its disregard for the religious perspective and the correct use of Jewish sources.

More Jewish historians would emerge over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Most of these scholars were, like Graetz, initially Torah observant, but had abandoned their religious beliefs, and the way they rendered Jewish history often reflected that bias. The preeminent Jewish historian of the 20th century was likely Simon Dubnow (1860–1941). His contribution to Jewish historical research included his magnum opus ten-volume World History of the Jewish People, but it also lacked a religious orientation.

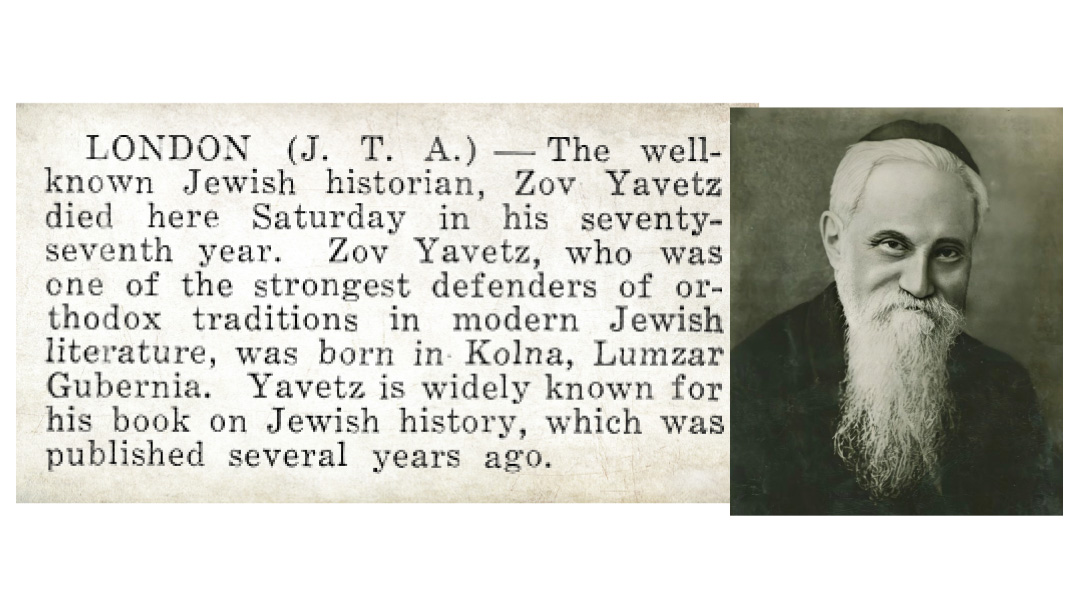

Between Graetz’s and Dubnow’s works, there emerged a 14-volume collection titled Toldos Yisrael, covering the entirety of Jewish history. Toldos Yisrael was the first work of such magnitude and scope to be published in Hebrew, and it was the first attempt to ground the full picture of Jewish history in traditional sources. The author of this ambitious project was Ze’ev Yavetz (1847–1924).

Born into a wealthy family in Kolno, Poland, near Lomza, Yavetz received a Torah education, but also gained proficiency in several languages along with a background in general knowledge. He became interested from an early age in studying Jewish history. He married Golda Pines, the sister of religious Zionist leader Yechiel Michel Pines; she managed the family business while Yavetz engaged in intellectual pursuits. He felt an urge to engage Graetz and others in argument, sharing the Torah view of history and highlighting many facets of religious life that he felt they had overlooked.

In 1887, Yavetz moved to Ottoman Palestine. Following a short stint as a winegrower and teacher in Yehud, he was soon hired as an educator in Baron Edmond James de Rothschild’s colony of Zichron Yaakov. The Baron’s officials didn’t approve of Yavetz’s educational vision, which included conducting classes in Hebrew and providing instruction in religion and Jewish history. He soon left for Jerusalem, where he began in earnest his lifelong work of writing Jewish history. He completed the first two volumes of Toldos Yisrael, which were published during his time in Jerusalem. He also contributed some of the first Jewish history textbooks to be used for instruction in religious schools.

His financial situation was dire, however, so in 1897 he returned to the Russian Empire, settling in Vilna. In 1902 he helped found the Mizrachi movement, but in 1906 his continued financial challenges forced him to move to Berlin and later to London, where he passed away in 1924.

He wrote tirelessly throughout all these years, doggedly pursuing his writing of history in the authentic Torah spirit, despite his acute economic straits. Toldos Yisrael was a corrective lens that highlighted omissions and contradictions of other historians. Yavetz meticulously elucidated Jewish history, rectifying misconceptions while reinstating overlooked sources. Ze’ev Yavetz’s unerring faithfulness in presenting Jewish history ensured his monumental legacy.

Opponents on the Right and Left

Yavetz persisted in his efforts despite critiques from all sides. Religious extremists dismissed his work as “bichelach” (little books), non-Torah works that no one should waste time reading. Secular scholars such as Simon Dubnow and Achad Ha’am wrote editorials highly critical of his methodology and use of sources and were generally dismissive of his entire endeavor.

On the other hand, Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, who was fascinated by Jewish history, shared with a student that he spent nearly a third of the money he received in wedding gifts to purchase Yavetz’s works.

Rebuking a Former Talmid

In response to Volume Four of Heinrich Graetz’s History of the Jews, Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch authored a series of essays between 1855 and 1858 decrying Graetz’s sloppy use of Talmudic sources, misquotes, lack of understanding of the words of Chazal, and his overall misuse of history — scathing rebukes to his former student. Graetz had lived in Rav Hirsch’s home for three years in his youth, and studied with him daily.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 975)

Oops! We could not locate your form.