Up, Up, and Away, Oh, What a Purim Day

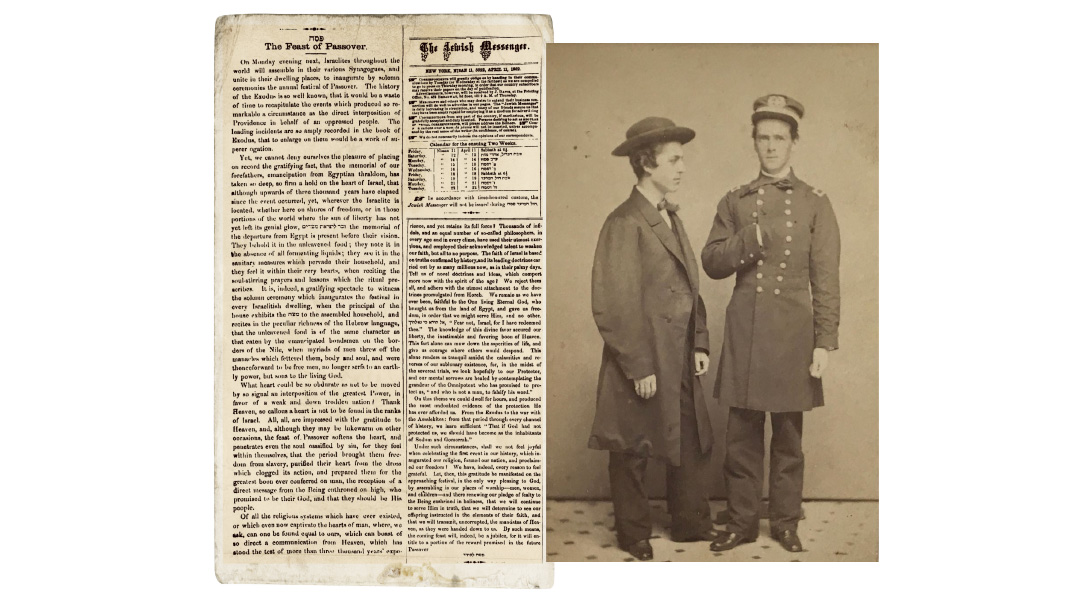

| April 2, 2024As the sun set, the Graf Zeppelin headed to Jerusalem, where its arrival coincided with Shushan Purim celebrations

Title: Up, Up, and Away, Oh, What a Purim Day

Location: Jerusalem

Document: Palestine Post

Time: March 1929

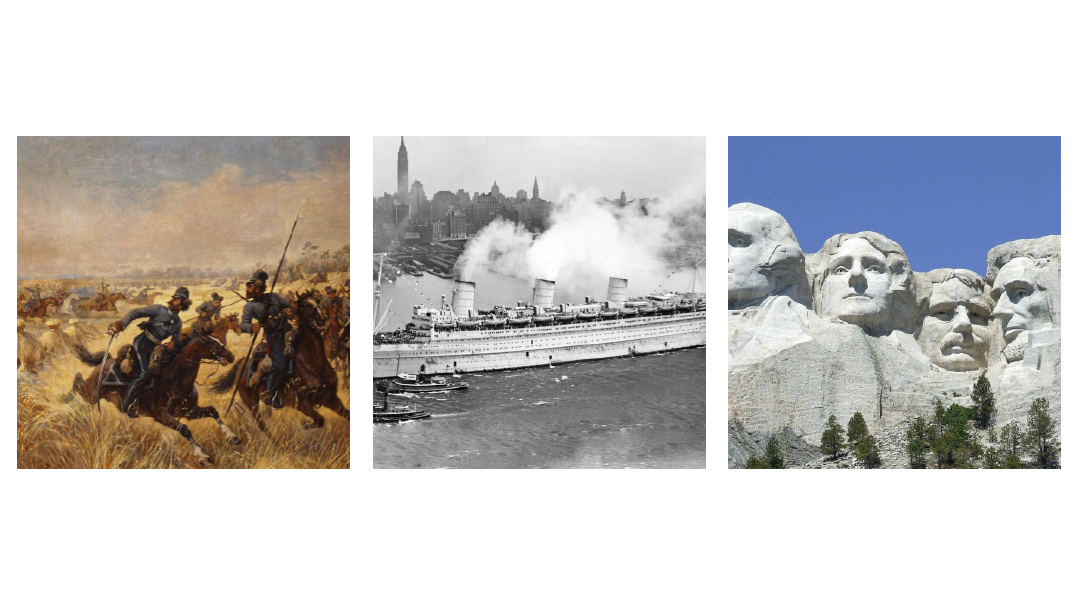

IN July 1900, two and a half years before the Wright brothers’ historic flight in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin successfully piloted a lighter-than-air rigid airship over Germany’s southern Rhine River Valley. Though dirigible development would eventually give way to airplanes, von Zeppelin’s lighter-than-air rigid airships controlled the skies during their golden age in the early decades of the 20th century.

Von Zeppelin’s success made Germany the world leader in the emerging rigid airship industry, and the aircraft he pioneered soon assumed the name of their inventor. By 1910, the first commercial airline in the world, Deutsche Luftschiffahrts AG, or DELAG, began operating a fleet of seven zeppelins.

Soon Great Britain, France, and the United States began building their own zeppelins, primarily for military use, but also with an eye toward commercial use. During World War I, the Zeppelin Company constructed nearly 100 military airships for the German Navy, some of which were deployed in the first aerial bombings in history in 1915, against Britain.

The years after World War I saw heavy international investment in the zeppelin industry, though the Treaty of Versailles prohibited Germany from manufacturing large airships. When the treaty was relaxed somewhat in 1925, the Zeppelin Company immediately embarked on the construction of a new class of airships, inaugurating the golden age of zeppelins. The craft made hundreds of nonstop transatlantic flights, primarily between Germany and Brazil, decades before any airplane accomplished the same feat.

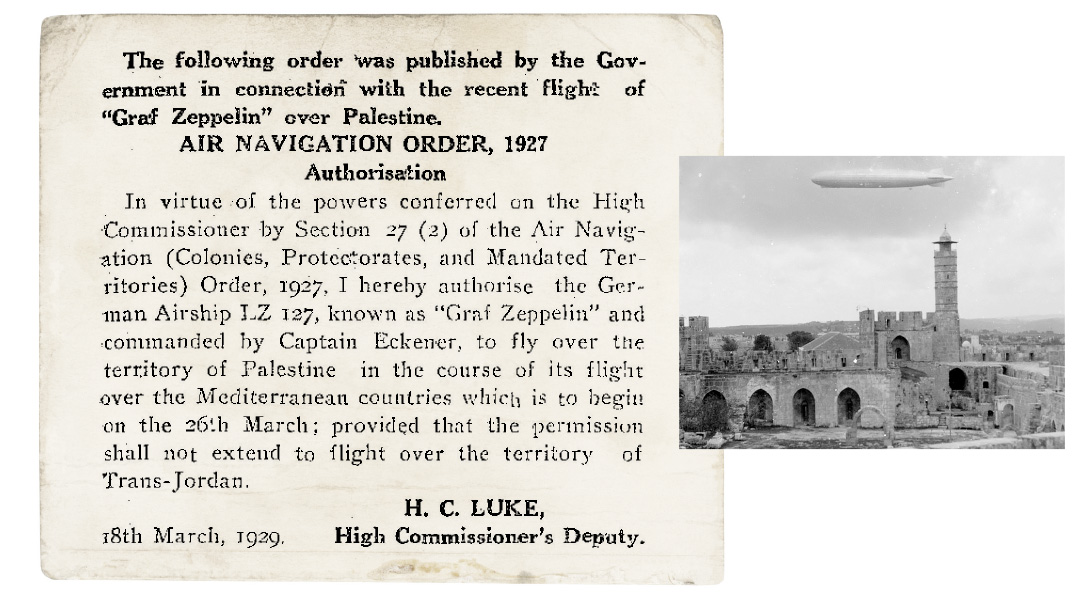

In July 1928, the Graf Zeppelin was launched in Germany amid great fanfare. It was the largest airship in the world at the time, operated by a crew of 36 with a capacity to transport 24 passengers. The Graf Zeppelin flew several promotional flights that were covered widely in the media, some of which broke records: transcontinental flights, an arctic flight, and a three-week circumnavigation of the globe in 1929.

Of particular interest were the Graf Zeppelin’s two trips to the Mediterranean and Middle East in 1929 and 1931. On the first of those flights, the Graf Zeppelin flew south from Germany to Vienna, Budapest, and Rome before heading east, reaching Palestine in late March 1929. Cheering crowds greeted it as it circled low over Tel Aviv and Jerusalem; it also descended to near the surface of the Dead Sea before heading back to Germany. It returned to the Middle East in April 1931 with stops in Libya, Cairo, Alexandria, pausing to hover over the Great Pyramid, before once again heading to Palestine, where it circled Jerusalem.

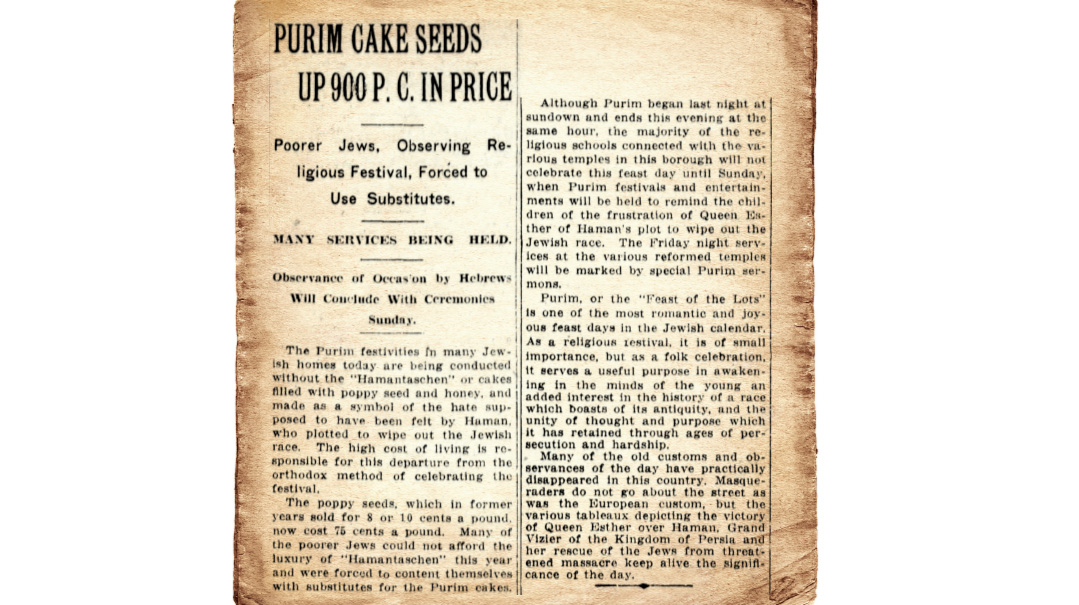

The Graf Zeppelin’s March 1929 visit to Jerusalem made a big impression on the city’s Jewish residents, according to contemporary reports. Two Jewish passengers, Dr. Hermann Badt and Dr. Wolfgang von Weisl, first arranged for dozens of bags of confetti to be poured out over Tel Aviv, where the annual Purim parade was being held.

As the sun set, the Graf Zeppelin headed to Jerusalem, where its arrival coincided with Shushan Purim celebrations. The passengers plotted to force a Purim landing in Jerusalem by faking a medical emergency. But Captain Hugo Eckener vetoed it due to the lack of proper ground support after dark. The sight of the airship, illuminated by a large searchlight from the German consulate and the bright lights of the German Colony, drew the entire population out into the streets. In a moment of reverence, Eckener ordered the engines to be cut; as the zeppelin hovered silently over the Old City, it resembled a “fiery chariot” in the light of the rising full moon.

The Hindenburg disaster in May 1937 brought an end to airship travel. The flammable hydrogen used by zeppelins was seen as too dangerous, and nonflammable helium was only available in the United States, which was unwilling to export it to Nazi Germany. Rigid airships soon faded into memory.

Nazi Airships

The director of the Zeppelin Company, Dr. Hugo Eckener, was an outspoken anti-Nazi, and didn’t hide his dislike of the new regime after it rose to power in January 1933. Following his frequent criticism and his refusal to allow the Nazis to use the Zeppelin hangar for a party rally, Hitler sidelined Eckener and nationalized the company. Eckener became persona non grata in German society. In the ensuing years, the rigid airships were emblazoned with the swastika and used for Nazi propaganda in flights around the world.

Jewish Airships

The idea of the original rigid airship was conceived by a Hungarian Jew named David Schwartz. He lived most of his life in Zagreb, Croatia, and studied mechanics on his own by reading books. During the 1880s, he began developing the idea for the airship, and constructed a prototype in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1893. He died in 1897 before the first test flight.

The DELAG airline was launched in 1910 through a partnership with German-Jewish shipping magnate Albert Ballin, owner of the famous Hamburg-America shipping line. Millions of Jewish immigrants to the US and other countries sailed from Hamburg on his ships during the great immigration. Ballin invested with Zeppelin in the airship industry, and tickets for commercial zeppelin flights were sold through Hamburg-America’s offices.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1006)

Oops! We could not locate your form.