Beef Boycott by Brave Women

| March 26, 2024“Whether or not these women’s fight succeeds, the Jewish People can be proud of it forever”

Title: Beef Boycott by Brave Women

location: Lower East Side, Manhattan

Document: Various Newspaper Clippings

Time: May 1902

Jewish women can be proud of themselves for their energetic protests against the meat vampires of the [Jewish] Quarter, and Jewish men can be proud of their women for this protest.… No man’s voice would resound with such an echo as do the women’s voices that weep, cry out about their own lives, those of their young children on behalf of the poor slave, harnessed in support of his half-starved family.… Whether or not these women’s fight succeeds, the Jewish People can be proud of it forever.

—Abraham Cahan, editor in chief of Der Forverts, May 16, 1902

America’s Gilded Age of the late 19th century saw the rise of trusts and monopolies controlling entire industries, manipulating prices at the expense of the average consumer. Labor unions began to organize, and economic conditions began to improve among unskilled labor during the Progressive Era, especially under the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. Early feminists launched the Women’s Suffrage movement, which would eventually culminate with the passing of the 19th Amendment in 1920, granting women the vote. This period of social ferment was the backdrop for the 1902 kosher meat boycott led by Jewish women on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

The great immigration peaked in the early 1900s, when millions of Eastern European Jews entered the United States, with the largest contingent settling in New York City. The Lower East Side emerged as one of the most densely populated places on the earth, and nearly 400,000 Jews lived in the neighborhood in its heyday.

In May 1902, the National Beef Trust of America raised the price of kosher meat from 12 cents per pound to 18 cents, on a whim. Kosher meat was already quite expensive relative to nonkosher meat in regular circumstances, and a sudden 50 percent increase made it unaffordable for many of the impoverished and lower-income immigrant families in the neighborhood. Though secularization was making rapid inroads among immigrants due to the perceived necessity to work on Shabbos and to the lack of religious infrastructure, especially in the realm of education, many Jewish women strove to remain loyal to their traditional roots by maintaining kosher homes.

On May 11, a group of butchers initiated the kosher meat boycott, refusing to purchase meat from wholesalers due to the price increase. But the beef trust proved too powerful, and the butchers quickly capitulated. By May 15, consumers had taken charge of the boycott. What made this organized consumer boycott unique was that it was spearheaded almost entirely by the Jewish women of the Lower East Side.

A May 15 article in the Yiddishe Tagblatt quoted an Orthodox Jewish woman, “Our husbands work hard… They try their best to bring a few cents into the house. We must manage, spend as little as possible. We will not give away our last few cents to the butcher and let our children go barefoot.”

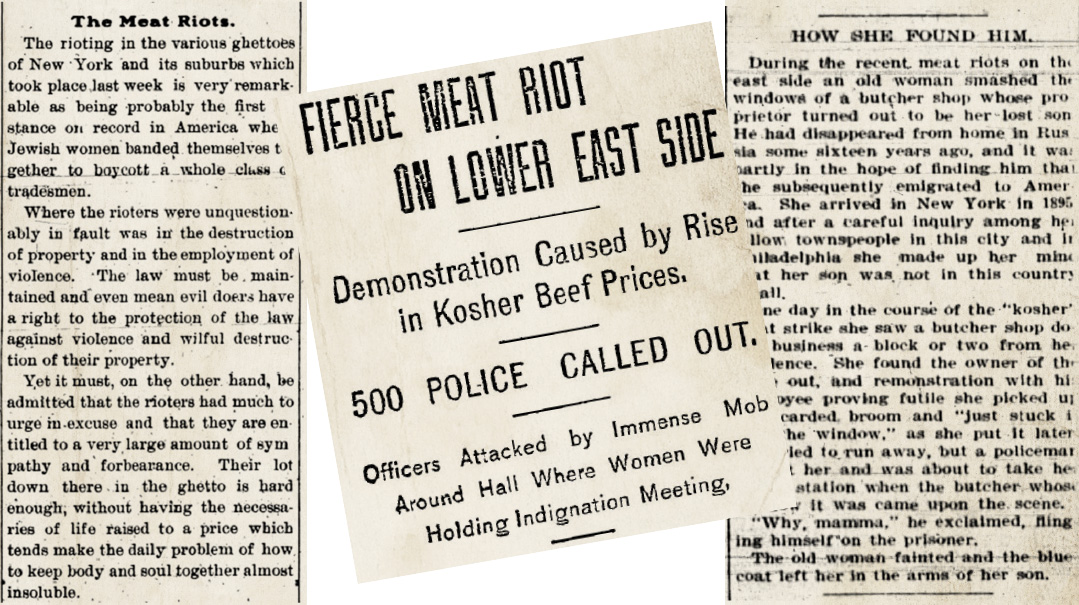

On May 15, nearly 20,000 Jewish women took to the streets to protest and enforce a broad meat boycott across the Lower East Side. The protests got violent, as the women rioted and threw bricks and meat at butchers’ windows. Women raided the butcher shops and took meat into the streets, poured gasoline on it, and set it on fire. They also verbally and physically accosted anyone who didn’t comply with the boycott, preventing them from purchasing meat. Law enforcement dispersed the protest with the arrest of around 70 women.

The New York Times reported on the coverage of the boycott in the Yiddish press, “The Hebrew newspapers in their evening editions charged the police with brutality, describing their treatment of the women demonstrators as ‘murderous,’ and worse than would have been meted out to them by the gendarmes of Russia.”

For the average participant in the boycott, this was a fascinating nexus of three disparate components of her life. As the primary mainstays of the home, women struggled with the daily tension of feeding their families. They were also on the front lines of maintaining traditional norms from the “alte heim,” such as kashrus; but they were painfully cognizant of the modern realities of their new home country. By organizing the boycott against the beef trust, the women fused the ideals of secular America with their mission to feed their families kosher meat.

A radical faction of the protestors soon took things a step further. On Shabbos morning, May 17, a group of women in the Eldridge Street shul left the ezras nashim and entered the main sanctuary during Krias HaTorah. They demanded acceptance of the meat boycott by everyone in the community, and endorsement from the communal leadership.

The reactions to this bimah takeover were mixed. The radical maneuver divided the women boycott organizers, and their strong initial unity was lost. On the other hand, the move raised awareness of how serious the situation was, and the men, along with the communal leadership, joined the boycott.

The violent protests began to subside, but the boycott continued. Jewish women on the Lower East Side raised funds to assist those who had been arrested by the police during the protests. They also printed and disseminated circulars around the neighborhood and beyond, to encourage others to join the boycott. Eventually the butchers sided with the boycotters as well, and they again stopped purchasing meat from the wholesalers.

By June 9, the beef trust capitulated, and meat prices were lowered to 14 cents a pound. The boycott had been a success.

Kosher Style

It should be noted that most of the supposedly kosher meat on sale in New York butcher shops was of very questionable legitimacy, and the chaotic local kashrus scene at that time is beyond the context of this story. But in their attempts to observe kashrus, many women purchased meat exclusively from certified kosher butcher shops.

Support from the Yiddish Press

The boycott and accompanying protests were covered widely in the general press. Most newspapers were ambivalent at best, and many were openly hostile to the Jewish women. Siding with the police in the name of public order, most media accounts portrayed them as non-English speaking immigrants stirring up mayhem. It was the Yiddish press who celebrated the boycott and provided the necessary support. The Forverts ran a headline, “Brava, Brava Jewish Women! Torn Bits of Meat Tossed in the Streets.” And the more traditionally oriented Yiddishe Tageblatt featured the headline, “Women’s Revolution! Uprising against Butchers!”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1005)

Oops! We could not locate your form.