Fighting for Freedom on the Holiday of Freedom

| April 16, 2024“There is no occasion in my life that gives me more pleasure and satisfaction than when I remember the celebration of Passover in 1862”

Title: Fighting for Freedom on the Holiday of Freedom

Location: Battlefields of the Civil War

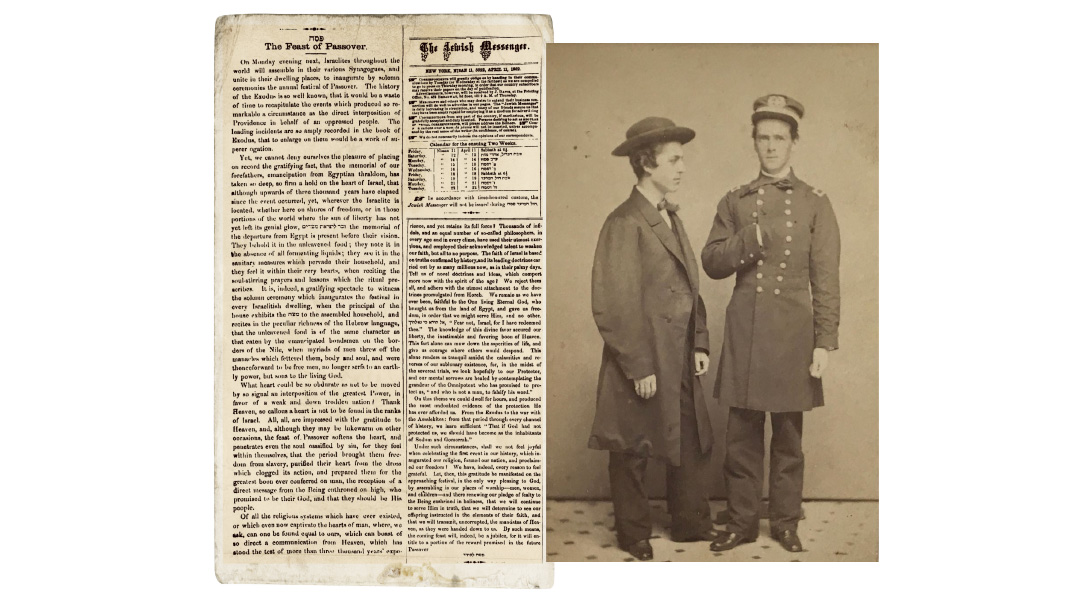

Document: The Jewish Messenger

Time: 1862

AS Pesach 1862 approached, a group of Jewish soldiers in the 23rd Ohio Infantry Regiment of the Union Army under Lieutenant Colonel (and future president) Rutherford B. Hayes wondered how they’d be able to celebrate the upcoming holiday under the battlefield conditions of the Civil War.

Informed of the dates of Pesach through correspondence with their families back home, the small band of co-religionists were granted temporary relief from duties in order to prepare for the holiday. From their winter quarters in West Virginia, they ordered a shipment of matzah from Cincinnati through one of the civilian traders licensed to sell supplies to combat troops in the field. Their order of seven barrels of matzah and two Haggadahs arrived on Erev Pesach, with no time to spare.

That Seder night was vividly recounted in a lengthy article titled “Passover: A Reminiscence of the War,” by Joseph A. Joel, one of the main participants. It was published in the Jewish Messenger on March 30, 1866, less than a year after the war’s end. Though Joseph seems to have either forgotten or embellished some of the details with the passage of time, the colorful description of Pesach in the Union Army is a unique account of religious observance by American Jews serving their country during the Civil War.

We were now able to keep the Seder nights, if we could only obtain the other requisites for that occasion. We held a consultation and decided to send parties to forage in the country while a party stayed to build a log hut for the services. About the middle of the afternoon, the foragers arrived, having been quite successful. We obtained two kegs of cider, a lamb, several chickens and some eggs. Horseradish or parsley we could not obtain, but in lieu we found a weed whose bitterness, I apprehend, exceeded anything our forefathers “enjoyed.”

We were still in a great quandary; we were like the man who drew the elephant in the lottery. We had the lamb, but did not know what part was to represent it at the table; but Yankee ingenuity prevailed, and it was decided to cook the whole and put it on the table, then we could dine off it, and be sure we had the right part. The necessaries for the choroutzes [charoses —Ed.] we could not obtain, so we got a brick which, rather hard to digest, reminded us, by looking at it, for what purpose it was intended.

Joel led the service with the other Jewish soldiers in the 23rd Ohio Infantry, beginning the ceremony with a prayer for Divine intervention “to preserve our lives from danger.” The men fully realized the dangers of battle that awaited them with the end of winter. In his postwar depiction of the Seder, Joel gave a detailed account of that memorable evening.

The ceremonies were passing off very nicely, until we arrived at the part where the bitter herb was to be taken. We all had a large portion of the herb ready to eat at the moment I said the blessing; each ate his portion, when — horrors! What a scene ensued in our little congregation, it is impossible for my pen to describe.

The herb was very bitter and very fiery like cayenne pepper, and excited our thirst to such a degree that we forgot the law authorizing us to drink only four cups, and the consequence was that we drank up all the cider. Those that drank the more freely became excited, and one thought he was Moses, another Aaron, and one had the audacity to call himself Pharaoh.

The consequence was a skirmish, with nobody hurt, only Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh had to be carried to the camp, and there left in the arms of Morpheus [a metaphor for sleep in Greek mythology —Ed.]. This slight incident did not take away our appetite, and, after doing justice to our lamb, chickens, and eggs, we resumed the second portion of the service without anything occurring worthy of note.

There, in the wild woods of West Virginia, away from home and friends, we consecrated and offered up to the ever-loving G-d of Israel our prayers and sacrifice. I doubt whether the spirits of our forefathers, had they been looking down on us, standing there with our arms [weapons] by our side ready for an attack, faithful to our G-d and our cause, would have imagined themselves amongst mortals, enacting this commemoration of the scene that transpired in Egypt.…

Since then, a number of my comrades have fallen in battle in defending the flag they volunteered to protect with their lives. I have myself received a number of wounds all but mortal, but there is no occasion in my life that gives me more pleasure and satisfaction than when I remember the celebration of Passover in 1862.

Though Joseph Joel’s sentimental view of that Pesach may have been clouded by the traumatic experience of the battles that followed the relative calm he described in his recollections, his focus on the camaraderie and temporary escape through the joint religious expression of celebrating Pesach in the wilderness was a common coping mechanism reminiscent of many postwar Civil War veterans’ memoirs. He certainly was a talented storyteller, providing a rare detailed view of the American Jewish experience under adverse conditions in the mid-19th century.

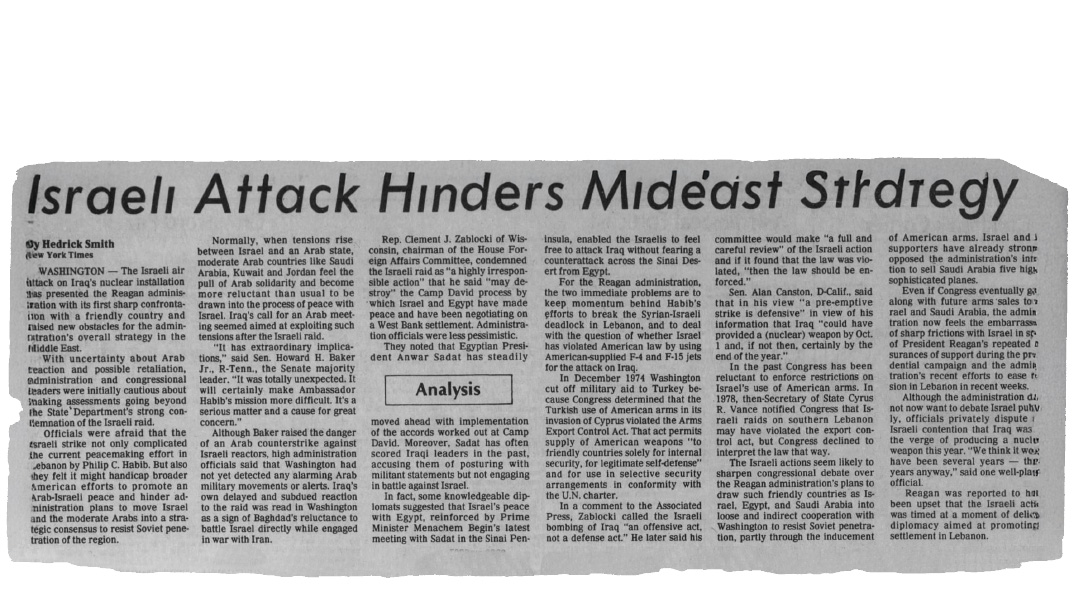

As the war drew to a close, Pesach offered an opportunity for reconciliation between American Jews on both sides. The War Between the States had divided American Jewry as well. General William Tecumseh Sherman’s March to the Sea concluded with the Battle of Savannah in December 1864. As the largest city in Georgia and one of the South’s most important ports, Savannah was essentially the goal of the entire campaign. With the Union Naval blockade closing the city’s access to the sea, Sherman’s troops overwhelmed the city’s defenses, and Savannah was occupied by the Union.

Dating to colonial times, Savannah’s Jewish community, numbering some 600 souls, was one of the oldest in the country. With Pesach approaching the following spring, Congregation Mickve Israel confronted an inability to procure matzah for the upcoming holiday. The local Jewish baker, A. Borchet, closed his establishment after his sons left to fight in the Confederate Army, and there was no other local source for matzah.

Turning toward their brethren in the North, the Savannah Jewish community strove for traditional unity, reviving the connection Jews maintained over the millennia that transcended temporary political differences and geographical borders. Citing ties of mutual obligation, Mickve Israel asked Jewish communities in Philadelphia and New York for “500 pounds of Passover cakes (matzah).” Eventually 35 synagogues, companies, and individuals from Northern Jewish communities donated $502.90 to bake and deliver 3,000 pounds of matzah for Georgia’s Jews.

On March 30, 1864, the Savannah Daily Herald ran an article entitled “Matzah Passover Bread”:

This morning 13 cases of Matza Passover Bread were received by the steamer U.S. Grant. The bread, a contribution of the Israelites of the north to their brethren in Savannah, is consigned to Mr. Brady. The Rev A. Epstein Reader of Congregation Mickve Israel is charged with its distribution. All who are able to pay for it will do so and to those unable it is a free will offering.

Several months after the war’s end, in October 1865, a Confederate Jewish veteran and Savannah native named Lawrence Lippman made an overture to Jews of the Union to renew ethnic solidarity.

It is but one year since this country was deluged with the greatest war that the world ever saw, one that needs no history to record it, no monuments to be erected, but is engraved in the hearts of every person, each cannot look back without a shadow, without the straining of the whole nervous system, and a “thank G-d” that they escaped with their lives. My father has learned me in my young days a scriptural text one that cannot be old, one that is engraved in the hearts of all true Israelites, it is “Coll Israel Achim” — we are all brothers, no matter from what part it may be, let it be from north, south, east or west, no distinctions.

From the brutal battlefields of the Civil War and its aftermath, and echoing through the pages of Jewish history of all eras, Jews of both the Confederacy and Union relate a tale of Pesach freedom and Jewish unity with a message that resonates for all time.

War Hero

Joseph A. Joel immigrated to the United States from England when he was 18 years old, and immediately enlisted in the Union Army at the outset of the Civil War. During the Battle of South Mountain in September 1862, Joel sustained severe injuries, with eight gunshot wounds and fractured bones in his right leg, right arm, and right shoulder; a punctured lung; and the loss of the tips of two of his fingers.

A few months later, Joel petitioned to rejoin his regiment, but was discharged on account of disability. His commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, was impressed, and noted in his diary, “The Jew who got eight bullet holes in his person and limbs… thinks he can stand service in a couple of months.”

The two corresponded extensively following the war, and Joel was invited by Hayes for a visit to the White House while he was president. Joel subsequently named his son Rutherford B. Hayes Joel. Hayes was honored by the gesture, and in a correspondence from 1873 expressed as such to Joseph.

“I am proud of your partiality and shall always regard with great interest the progress of the young gentleman. I shall try to remember him in some substantial way. Let him be as brave and honorable as his father and he will be a credit to his parents and namesake.”

A Jewish House Divided

The Jewish community of the United States was divided between the Union and Confederacy, and each displayed loyalty to its sovereign government during the war. This sometimes led to divisiveness between Jews, who found themselves on both sides of the battlefield.

A Jewish Union soldier named Simon Brucker found himself in Suffolk, Virgina, as the High Holidays approached in 1862. In their correspondence, his parents alerted him to the presence of a Jewish community in nearby Norfolk, and he found his way to services there on Rosh Hashanah.

Upon arriving in the synagogue, he wrote, “I was pleased to find a large congregation engaged in prayer. Oh! It made me feel as though I were at home among friends once more.”

He was soon disappointed to discover that his Union military uniform made him feel somewhat unwelcome in this Southern Jewish community. Though it was overall a hospitable reception, the animosity was clearly present.

“All the Yehudim in Norfolk are embittered against the Northern soldiers, and I had several little arguments with some of them. I found most of them pretty reasonable excepting the young ladies; they can out-argue the smartest statesman in the world according to their own way.”

A Forgotten Hero

Rev. Samuel Myer Isaacs (1804-1878) was born in the Netherlands and raised in Britain, where he ran a Jewish orphanage. After arriving in New York in 1839, he became the first chazzan and preacher of Congregation B’nai Jeshurun in New York, which he left in 1847 following a schism there. He then became rabbi of Congregation Shaarei Tefila, remaining there until his death.

As editor of the Jewish Messenger from 1857 to 1878, Isaacs forcefully opposed the Reform movement, seeing it as a threat to traditional Jewish observance. He used the paper as a platform to advocate for preserving halachah and for a variety of social and political issues — including abolition of slavery, which led him to the loss many of the newspaper’s Southern subscribers. As a result of his advocacy, Isaacs was among the clergymen to officiate at the funeral of President Abraham Lincoln.

This article is primarily based on the research and writings of Professor Adam Mendelsohn in his excellent book Jewish Soldiers in the Civil War.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1008)

Oops! We could not locate your form.