Pockets of Poppy Seeds for Happy Holiday Hamantaschen

| March 12, 2024Hamantaschen have played a large role in Purim celebrations for centuries

Title: Pockets of Poppy Seeds for Happy Holiday Hamantaschen

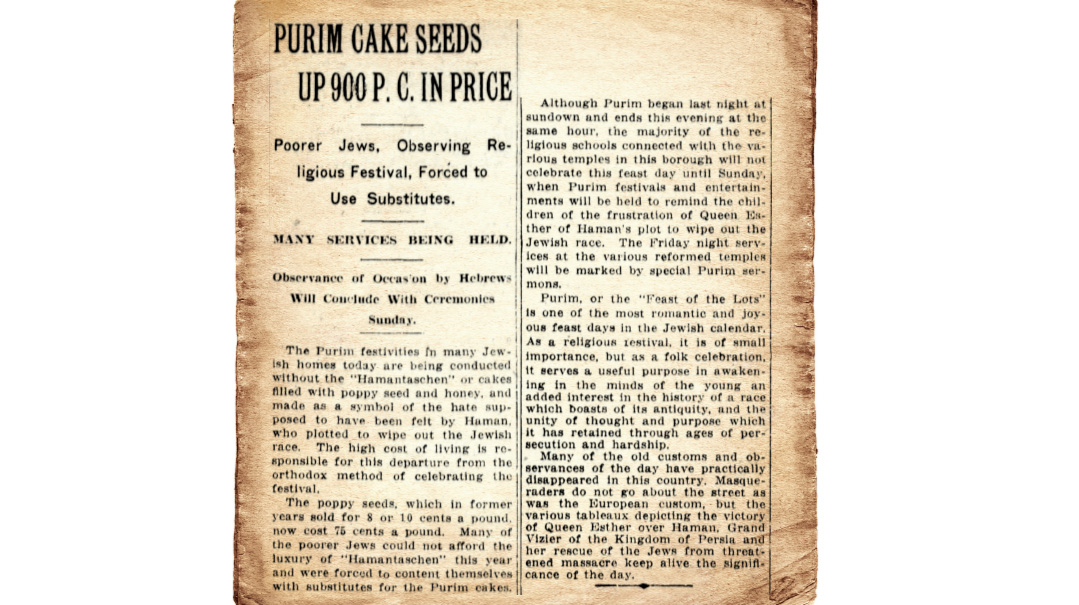

Location: New York

Document: Brooklyn Daily Eagle

Time: 1917

Jewish studies scholars have unfortunately not given the topic of culinary history the attention it deserves. Very few scholars have researched this neglected subject.

—Mordecai Kosover, Yiddish author, 1965

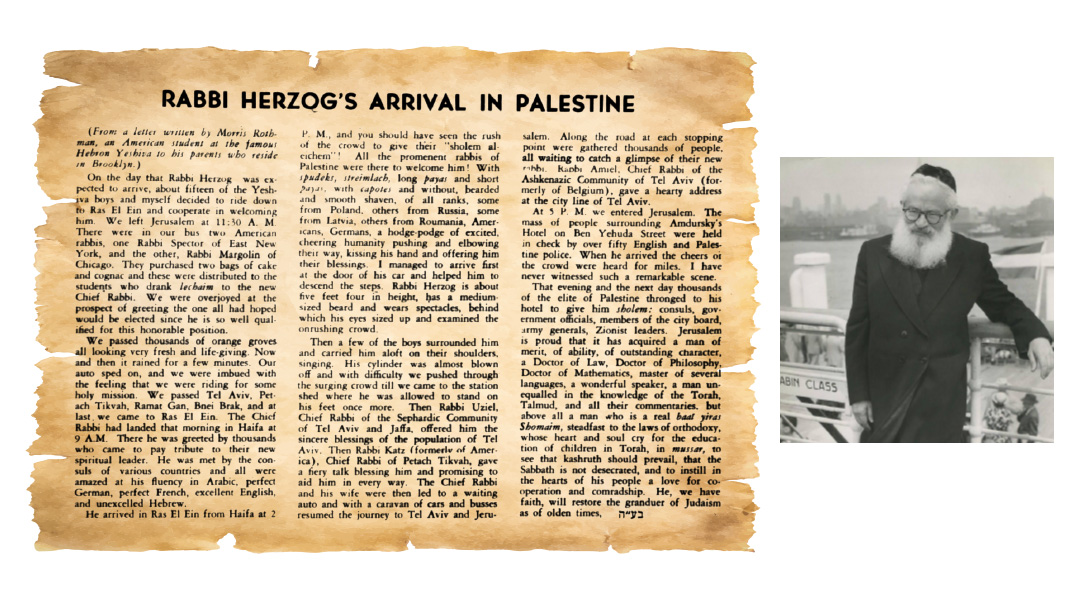

In the early days of Adar one year, and my great-grandfather [Rav Yaakov Berlin] noticed on his way to shul that the baked goods vendors… weren’t selling any of the honey- and poppy-flavored pastries usually baked in honor of Purim. The custom had always been that from the beginning of Adar, the bakeries would sell these three-cornered Purim cakes referred to as “Haman-taschen.” The children’s excitement in purchasing them greatly fed into the Purim atmosphere.…

Upon inquiry, my great-grandfather discovered that due to the unusually high prices of wheat flour that season, the bakers had purchased enough flour for such necessities as bread, but not sufficient supplies for cakes and treats. Later that day, he summoned two of the main bakers in town and gave them each 30 gold coins to procure additional flour for the express purpose of baking and selling hamantaschen as was the yearly tradition. The community was happy, and this special minhag wasn’t lacking that year due to his efforts.

—Rav Baruch Epstein, Mekor Baruch, Volume 2

Though shapes and ingredients vary widely, hamantaschen in Yiddish (oznei Haman in Hebrew), have played a large role in Purim celebrations for centuries in Jewish communities around the world with diverse communal traditions.

Various explanations have been offered about the name. The Yiddish word for pocket, tasch, possibly refers to Haman’s pockets, which he emptied of contents to bribe King Achashveirosh to exterminate the Jews. Alternatively, it may refer to the Hebrew word tash, which means weaken, evoking the idea of weakening Haman through the miracle of Purim.

However, it’s much more likely that tasch derives its name from the dough pocket containing some sort of delicious filling. This is especially likely given the custom of preparing kreplach on various Jewish holidays; hamantaschen likely evolved from this dumpling-like food.

Unless tasch actually refers to his own pockets, the connection to Haman is somewhat mysterious. The most popular filling for centuries was poppy seed or mohn, so the pastry was given the German name mohntasche. German-Jewish bakers in the 19th century marketed them with an added ha- prefix to give it a Purim spin, and the name hamantaschen stuck. Although the poppy seed filling ’s popularity was due to the tastes of European Jews, a symbolic meaning grew around it, linking it to the seeds eaten either by Queen Esther or by the prophet Daniel in Nevuchadnetzar’s palace.

What could possibly be the historical background referring to the pastry as oznei Haman? The 18th-century sefer Zera Shimshon, by Rav Shimon Chaim Nachmani, provides a possible answer.

Haman tilted his ears to listen to his wife, who advised him to construct a wooden pole for hanging Mordechai. To commemorate this, we eat sweet pastries called “Haman’s ears,” because the central miracle of the story was his construction of these gallows, where he himself was ultimately hung following his altercation with the King.

Regardless of its etymology, the pastry’s appearance signaled Purim’s imminent arrival, and therefore was a cause of excitement. Famed Slabodka talmid Rav Avraham Elya Kaplan recalled, “One was able to get hamantaschen at the Rebbetzin from Tu B’Shevat and on. This indicated that Purim was right around the corner.”

Throughout Jewish history, Purim has offered the opportunity to engage in humor, theatrics, and comedy. Many Purim parodies and plays have been written and occastionally even performed over the millennia. Some texts use hamantaschen as a springboard for humorous Purim Torah. A 16th-century play includes dialogue in which a questioner asks why the Jewish People ate “Haman” for 40 years in the desert (making a play on words with ha-mahn). His interlocutor responds, “There is a mitzvah on Purim to consume oznei Haman, which are made from flour mixed with oil, and that’s why the pasuk continues that it tasted like a ‘cake dipped in honey’ [tzapichis bidvash].”

A 19th century compendium of Purim Torah poses the following “halachic” question:

A new baker has come to town and wishes to initiate a new custom not seen before. He wishes to bake and sell hamantaschen that have four corners instead of three… Many townspeople object that this is a breach of tradition.

The “halachic” authority responds, “This is a great sin, to deviate from our long-held custom and instead make four-cornered hamantaschen… In addition, these hamantaschen would require tzitzis, as a result of having four corners, and not being a garment worn exclusively at night [which would absolve it from the requirement of tzitzis], because the mitzvah of hamantaschen applies the entire day of Purim…”

Three Corners

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the three-cornered tricorne hat was popular among European aristocracy as military dress, and even among some civilians. In Russia, senior officers generally donned the tricorne, so the legend developed that Haman must have had a similar headdress, and this design found its way into the pastry.

Others explained that the three corners honored the three Avos; or that they symbolize the dispersion of the Jewish People to the corners of the world; or that they recall the shape of the dice used by Haman.

Haman’s Limbs

Sephardic communities in Greece and Turkey baked a pastry with almonds and cinnamon and rolled into a shape of a finger to resemble Haman’s finger. Moroccan Jews prepared a round bread with two hard-boiled eggs in the middle as Haman’s eyes. Haman’s fleas were symbolized in a Persian Jewish cookie topped with black seeds. Debla is a North African Jewish delicacy, rolled into the shape of a megillah.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1003)

Oops! We could not locate your form.