Nothing but Net

| April 11, 2022Though his playing career came to an end at age 27, it’s not even close to game over for Tamir Goodman

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Personal archives

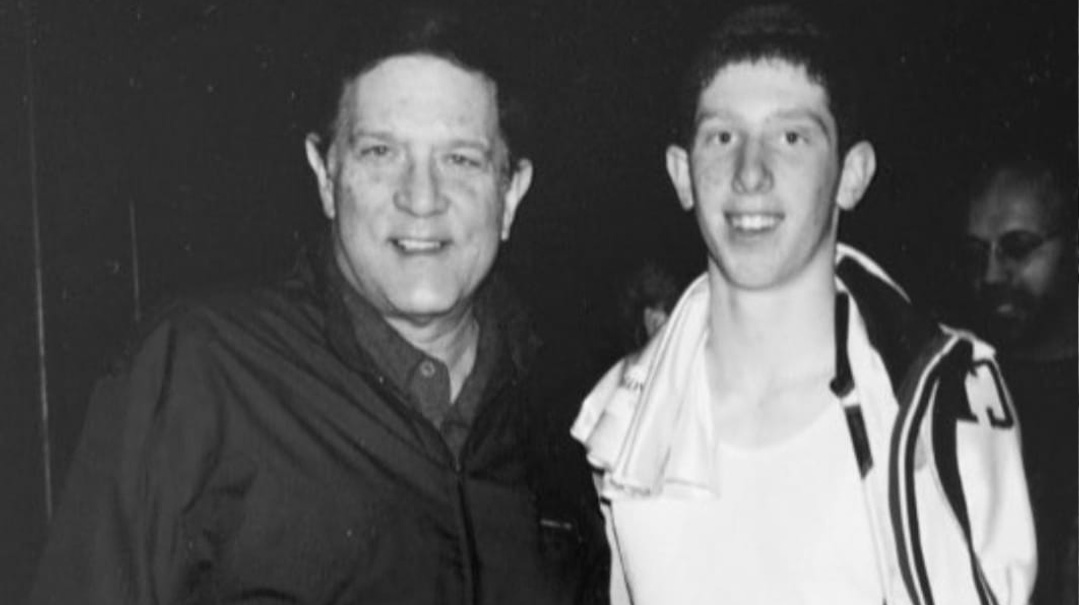

He was the talk of the town, the hope of his coach, and ranked the 25th best high school player in the US. At 6 foot 3, the gangly redheaded kid from Baltimore brought a golden reputation — he’d averaged more than 35 points per game in 11th grade — to his new career in college basketball.

But Tamir Goodman brought something else to the court: a staunch resolve that his identity as a Torah-observant Jew would always come first. Years later, forced by injuries to retire after a career that never had a chance to fulfill the breathless expectations of sportscasters across America, it’s not even close to game over for Tamir — today a coach, motivational speaker, entrepreneur, and inventor. Because all this time, his eye was on a different prize.

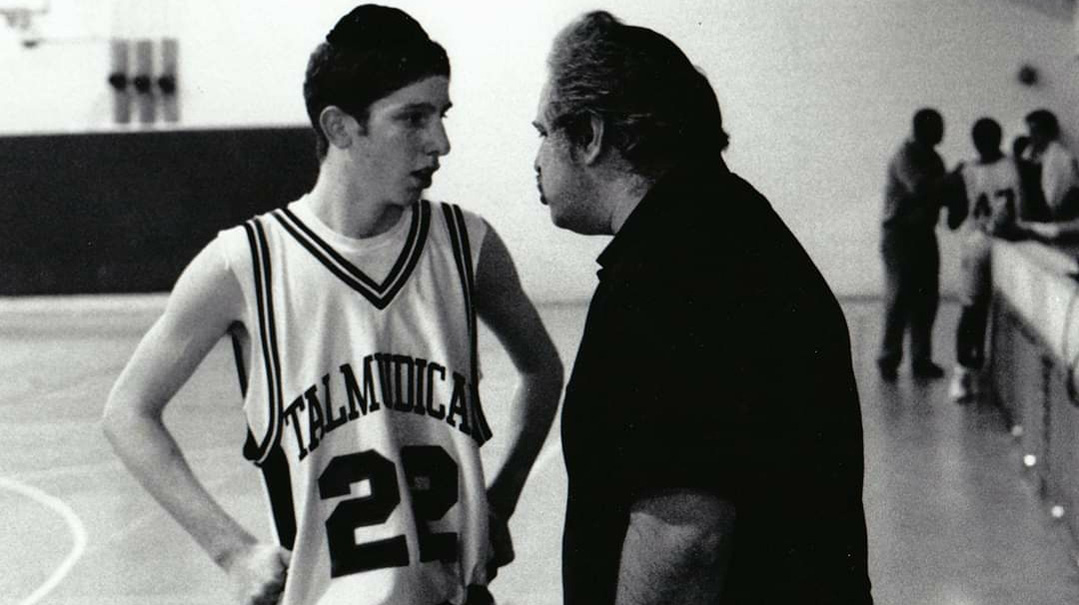

Tamir learned a valuable lesson from high school coach Harold Katz: “Don’t do anything to embarrass your Creator”

Squaring the Circle

Tamir Goodman became a nationally recognized figure in 1999, when he was dubbed “the Jewish Jordan” — a reference to greatest-of-all-time basketball player Michael Jordan — by Sports Illustrated, the king of all sports magazines. When SI crowned a skinny 17-year-old from Baltimore — and did we mention Orthodox Jew? — as a “Jordan,” the world sat up and took notice.

Tamir Goodman was born in 1982 to a close-knit, Torah-observant family of nine children. His parents kept a warm, open home, and he had a typical childhood, attending the local Talmudical Academy, an Orthodox day school.

But from age five, the lanky redhead was drawn to the basketball court, and his unusual talent was obvious. “I liked all sports,” he says, “but nothing came close to my love of basketball. And that’s probably what set me up for my basketball journey. If you’re going to reach the highest level at anything in This World, you really have to love it. The love has to be so deep, and you have to be so committed, otherwise, the hours spent, and the work… because you’re literally pushing yourself to tears every day in training. It’s not worth it unless you really, really love it. I love the game.”

Those hours on the basketball court were the bright spots in his life, because school was a painful struggle for Tamir. At age 15, he finally found out the reason why: severe dyslexia.

“Reading, writing, and basic math are a huge challenge for me. It was very frustrating not to be able to do simple tasks on a daily basis that other people could do. But life is about working with what we can do instead of focusing on what we can’t.

“I only heard recently that the doctor who diagnosed my dyslexia told my coach, ‘I don’t even know how this kid can play.’

“ ‘Why is that?’ the coach asked.

“ ‘Because,’ said the doctor, ‘he can’t tell the difference between a circle and a square.’ ”

But Tamir clearly had an instinctive feel for basketball. And it didn’t seem to matter if the basket was a circle or a square. By the time he was 17, Tamir was ranked the 25th best high-school player in all of America, averaging more than 35 points per game and attracting so much attention that Talmudical Academy had to rent larger courts to accommodate all the spectators clamoring to see the tall redhead in action.

That’s when the University of Maryland came calling.

And the name Tamir Goodman exploded onto the world stage.

“No matter what happens, you must always stay humble and understand that your talent comes from Hashem.” Dad’s advice was a transformative moment

A Household Name

Early in 11th grade, when Tamir was 17, Coach Billy Hahn from the University of Maryland (UMD) saw him play in a high school game. UMD is a Division 1 (D1) school, the highest level of intercollegiate athletics, and the coach immediately offered Tamir a full four-year scholarship, telling him, “I’m already sure, but I’m coming back tomorrow to see your game — not because I have any doubts, but just because I love watching you play.”

UMD was Tamir’s favorite team, but he didn’t immediately accept the offer. He could only commit, he told the coach, if he wouldn’t have to play on Shabbos or chagim.

“After that my whole life changed.” He remembers the storm that erupted. The media got wind of the story, and it became the most compelling news for basketball followers and many others around the country. “I got 700 media requests in one week: ABC, NBC, CBS, ESPN… Everyone wanted to find out why I wasn’t going to play on Shabbos.”

His quiet private life became a very public life very quickly.

Sports Illustrated wrote a four-page article about the budding star who would sacrifice his career for Shabbos. Their photographer traveled to Baltimore and shot some standard pictures of Tamir shooting basketballs in his backyard. “Then I stopped the photographer,” Tamir says. “I told him, ‘I know that millions of people are going to be seeing this magazine, and that you’re an NBA photographer, but it’s not really about me, this media attention. It’s about Israel and about the Jewish People, and I’d like to represent that.’ ”

“How can you do that?” asked the photographer, at which point Tamir asked him to please follow him to his room.

“Even though it was the afternoon, I took out my tefillin and I put them back on, and I took out my siddur, and I said, ‘This is how we pray in the morning.’ ”

Tamir was the first person to be pictured wrapped in tefillin in SI, and got nicknamed “the Jewish Jordan.” His story rapidly flooded virtually every sports outlet.

“What are your priorities?” Tamir was asked in one televised interview.

“My priorities are to be a basketball player and a G-d-fearing Jew,” he answered. “I realize G-d gave me this talent, and He can take it away from me just as fast as He gave it to me.”

Memories of a childhood visit with the Lubavitcher Rebbe were always in the background

Like the Eye of a Needle

Tamir’s priorities got tested soon after the media’s glowing coverage flooded airwaves and TV screens. Within months, the University of Maryland reneged on its promise. They told Tamir he could keep his scholarship, but he’d have to play on Shabbos.

“Coach, I love the program so much,” Tamir replied, “but for Jewish people, Shabbos is more important than basketball.” And with that he turned down what was likely the most sought-after basketball scholarship in the country.

Then Towson University, a D1 university in Baltimore, phoned. “I’m not Jewish,” the coach said. “Nobody on the team is Jewish. But the guys on the team read about you and asked me to recruit you. They respect that you didn’t want to play on the Sabbath. Can we learn more about your religion?”

Tamir still remembers the day the head coach and assistant coach came over to his house. His father came out of the kitchen holding a Jewish calendar and started paging through it with the two non-Jewish coaches. “Let me show you when Tamir can play and when he can’t,” he said. “Rosh Hashanah, no. Yom Kippur, no. Succos, no. And all the Saturdays.”

The coaches took down the dates and details, and then approached the head of the league. “Question,” they said. “Is there any way you can change our entire schedule, and all our flights, TV contracts, hotel reservations, and radio broadcasts… for one incoming Jewish athlete?”

Unbelievably, the answer was yes.

Tamir Goodman became the first person to earn a scholarship to play Division 1 basketball without playing on Shabbos and chagim, and with permission to wear his kippah on the court. “I thank G-d every day that I was able to live out my dream,” he says with the trademark sincerity that hasn’t dimmed even decades later. “So much good has come from that, and I’m forever thankful for that.

“I always feel that if you hit a stumbling block, you’re one step closer to reaching your potential. G-d is just giving you a springboard to get to where you need to go, that’s all it is; He’s just showing you the way to get there. Without learning something along that process, you’re just not going to be able to get it.”

As a draft choice for Towson University, and Maccabi Tel Aviv’s 2002 Rookie of the Year. “Now I understand why it all happened”

Dad’s Only Advice

Was it the sum total of his upbringing that gave teenaged Tamir the strength to hold tight to his values despite dream offers that would turn most heads? Or was there a blinding moment of clarity that became a game-changing force in his life?

Tamir says there was a single moment that informed his entire attitude toward sports. “On a Sunday afternoon in 1990, when I was around eight years old, I was playing for a local league in Baltimore, and I hit the game-winning shot just as time ran out. It was the biggest shot I’d ever made in my life at that point, and after I made the shot, I ‘raised the roof,’ pumping my fist in the air, like I was the best player in the world. Then I ran over to my father z”l, and I gave him a hug in the stands, and he gave me a hug.

“When we were in the car about to head home, he looked at me in the rearview mirror. And he said, ‘You know, Tamir, I’m very proud of you for making the winning shot, but a Jewish person never reacts like that. You must always have humility, you must always remember that Hashem is everywhere, that Hashem is on the basketball court with you, Hashem is everywhere you go, and you must always play that way.

“ ‘You shouldn’t react in an arrogant way, like your talents come from yourself, but always remember that it comes from Hashem. No matter what happens, you must always stay humble and understand that your talent is from G-d.’ ”

Tamir pauses. “That was a transformative moment for me and my career. And that was the only time my father ever gave me basketball advice. He was only unconditional love and support and always had an ear to listen. Throughout youth basketball, high school, college, and seven years of professional ball, he never corrected me about anything I should have done in a game, never ever. Except that time.”

Home Team

There was a slow but steady buildup of unspoken messages, too, that strengthened Tamir’s determination to place Shabbos and mitzvah-observance above any career consideration. “My parents made Shabbos really fun, so as a kid, Shabbos was great for me. As I got older, basketball got more serious and very intense. For me, in my service of Hashem, it was very clear to me that I needed that break for 25 hours every week to work on my inner struggles, to work on my relationship with Hashem, to work on my purpose in This World, and my relationships with my family.

“So it was always very clear that I wasn’t going to play on Shabbos. That was not a challenge for me, even at the biggest games. I just knew it wasn’t an issue.” He smiles and says, “I’m not a tzaddik, I have a million other struggles that I continuously work on and try to get better at — but playing on Shabbos wasn’t one of them.”

Tamir’s family attended Chabad of Park Heights in Baltimore, headed then and now by Rabbi Elchonon Lisbon. “I remember on Friday nights, in shul, in between Minchah and Kabbalas Shabbos, they would learn. I guess the background noise of all those Friday nights penetrated, the message of taking something physical and making it holy, that Hashem wants us to uplift everything, each person in their own way. That every person has their mission, everybody has to make a dwelling place for Hashem through their own unique talents.”

Hearing those messages every Friday night spilled over into Tamir’s subconscious. “It even affected my attitude toward basketball — I saw it as ‘Hashem wants me to play basketball, but I have to play in a way that will make a kiddush Hashem.’ ”

In basketball, Tamir found a pulsing, pumping metaphor for some of Judaism’s greatest truths. Coach Harold Katz, his high school coach, never let him settle, never let him cut corners, and taught him how to pick himself up at a young age. “If you want to reach your dreams, here’s what it’s going to take,” Coach Katz told him. “You either want to do this, or you don’t want to do it.”

Before every game they played for Talmudical Academy, Coach Katz would tell the team, “Don’t do anything to embarrass your Creator.” The message: You’re playing basketball as servants of Hashem, and we’re going out there to make a kiddush Hashem.

“In my opinion,” says Tamir, “the greatest part of our avodas Hashem is our relationship with Hashem, that Hashem wants a relationship with us, and when I say relationship, I mean an authentic relationship. Hashem could have just been alone, but decided to humble Himself and bring Himself down to This World and give us the Torah and mitzvos so that we could have that relationship. And the most important thing is the authenticity, not just going through the motions.

“Envision how when you dance on Simchas Torah, you feel like your whole body is given over to Hashem, and you just feel so one with your purpose in This World. I think sport has a great advantage in helping us achieve that singularity of purpose because you can’t fake devotion or accomplishment in sports. You can’t just go through the motions — if you’re playing hard then you’re living it mind, body, and soul.”

Still in the game: Tamir and basketball camp helper Amar’e (Yehoshafat) Stoudemire and Benny Friedman

If You Build It

After all it took to get into a D1 program that would accommodate him, Tamir only stayed until December of his sophomore year. The first coach was fired, and the situation with the new coach quickly plummeted.

“I was physically attacked by my new coach at Towson, which broke me physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I felt so devastated that that happened to me, and I couldn’t wrap my head around it, why this person could take away all my hard work. It was the lowest I’ve ever been, the furthest I’ve ever felt from Hashem in my life.”

Tamir finished his course requirements, but his star streak seemed to be irrevocably broken. The gangly kid who’d captured hearts and headlines with his winning shots had crash-landed, and his career looked like it was over before it had ever really begun.

But eventually, Tamir picked himself up. He still couldn’t understand why this had happened to him, but he did understand that everybody has a mission in This World — and his was through basketball.

“I would not let somebody else take me away from who I am,” says Coach Tamir today. “Running away from my identity was not making me feel better, so I needed to come back stronger than ever. I channeled this experience. I know what it’s like to have a coach break you down. Now I’m the guy, as a coach, who builds you up.

“The only healing I have is trying to uplift as many people as possible. I’ve been able to coach and hopefully inspire thousands of kids and players from all over the world, of all ages and backgrounds. Had I not gone through this, I would never have had that sensitivity. It helped me reach my potential and gave me clarity about what Hashem is expecting me to accomplish in This World and to realize the creativity I have within me.

“And this is the only way, still today, that I could move forward after what happened to me. You take a kid who’s struggling in life, who doesn’t have self-confidence, and if somehow, through basketball, you teach them to have self-confidence, that’s almost a higher level of joy than anything you accomplished as a player.”

This desire to build has become Tamir Goodman’s driving force. Not only did he build himself back up, he’s in the business of building up everyone and everything around him, whether it’s people or businesses. He’s taken Rebbe Nachman’s famous mantra of “If you believe you can break it, believe you can fix it” to a whole new level.

At a basketball clinic with former NBA all-star Michael Redd in Jerusalem, where Redd was visiting to invest in Israeli hi-tech

Traded Places

In 2002, Maccabi Tel Aviv, one of Israel’s best professional basketball teams, offered to sign Tamir for a three-year contract. Today, in hindsight, Tamir can clearly connect the dots between his truncated college career and his beautiful family.

“The way I met my wife, Judy, is a very great miracle. She was also an outstanding athlete who received a lot of D1 scholarship offers to compete, and she turned them all down because of Shabbos and moved to Israel!”

At that time, Tamir had just gotten traded to Givat Shmuel, a less prestigious team than Maccabi Tel Aviv, and on paper it looked like a terrible thing for his career. Judy was studying at Bar-Ilan University. A friend of hers asked Tamir to come visit kids in the hospital, and he agreed. “Through the mitzvah of going to visit the kids in the hospital,” he says, “I met my wife as well.”

The two began to talk, and Judy mentioned that she was in Israel studying and volunteering after turning down her athletic scholarship offers because she didn’t want to compete on Shabbos.

“I was like, wow! Now I understand why I got traded!”

Today Judy Goodman is a personal trainer, holds an MA in English literature, and works as a copywriter at a top Tel Aviv marketing firm. Most importantly, she’s Tamir’s partner in a busy and blessed life, as together they raise five children — Oriyah, 17, Matanel, 14, Tiferet, 12, Yahav, 10, and Nevo, 4 — in their Jerusalem home.

After playing for some of Israel’s top teams, where he earned the endearing nickname “Big Rabbi” (and taking a break to serve in the IDF, where he was awarded Most Outstanding Soldier), Tamir retired from professional basketball in 2009, at age 27, after suffering several career-ending injuries including knee injuries, the complex dislocation of a finger, and shattering several bones in his hand.

How does one suffer several career-ending injuries? One has to have the drive of a Tamir Goodman.

“I never gave up until I couldn’t walk up the stairs anymore, couldn’t pick up my kids. It’s how I live today, always in pain. I never quit, I did every surgery possible, and I’m very proud of that.

“I remember calling my wife from the locker room and saying, ‘Hashem doesn’t want me to play basketball anymore.’ I had the clarity to say that because I did anything and everything to go as long and as hard as I could — every therapy, every surgery — and even though I miss playing the game, I know that Hashem said it was time. That gave me closure.”

“The struggles I’ve gone through have made me more sensitive to others’ struggles.” Last summer’s basketball camp in Jerusalem

Strings Attached

Tamir was forced to abandon his dream and retire from basketball at age 27. With the gift of hindsight, he says the loss brought him gains and gifts.

“Losing out on my dream at the height of my career has made me a better person,” he says now. “The struggles I’ve gone through have made me more sensitive to other people’s struggles, both internal and external. I wouldn’t be who I am without that loss.”

Even after retiring from the professional leagues, the sport is still a big part of his life. Tamir currently works as an in-demand motivational speaker, coach, educator, entrepreneur, and a sports and business consultant. He’s also the director of Hoops for Kids, a nonprofit organization that provides after-school basketball programs and mentorship for underprivileged kids and at-risk youth in Israel. He has coached thousands of kids and run basketball camps and programs across the US. He also founded Zone190, a training device being used in the NBA, and developed two tech innovations for basketball players.

His Sport Strings Tzitzit was sparked by his own frustrations with wearing tzitzis while playing. As a high school and Division 1 college basketball player, Tamir always wore a kippah while playing ball, but was told that it wasn’t recommended to wear tzitzis during athletics because the perspiration and wear and tear that the tzitzis would be exposed to could degrade the holiness of the garment.

Tamir kept his tzitzis on though, playing professional basketball while wearing traditional cotton tzitzis under his jersey. Their design, fabric, and fit didn’t hold up well. After he retired, he decided to create a line of tzitzis that appealed to a modern aesthetic and that could withstand rigorous activity so active Jews everywhere could adhere to the mitzvah of wearing tzitzis in comfort and style, without worrying about damaging the garment.

The resulting “Sport Strings” are created out of high-performance athletic materials. These tzitzis offer a compression fit, UV protection, anti-odor and anti-microbial properties — and an OK kosher certification.

With participants in Hoops for Kids, a program that teaches life skills, through basketball, to underprivileged youngsters

The Game’s Never Over

If you judge Tamir’s career through a professional sports lens, you might dismiss it as a disappointment — the vaunted high school star and media darling forced to retire by age 27 without any notable awards or titles.

But Tamir views his life through a different lens. And seen that way, his career is still going strong, still climbing, still accruing success.

“I’m always going to miss playing the game of basketball,” he admits. “When you’re playing on the biggest stage and you lose that, there’s nothing else to simulate that experience. So when I stopped playing, I felt like I stopped living my dream.

“At the same time, I felt so lucky to be Jewish. Because without that anchor and blueprint, I see how easy it is for a person to fall into depression, drugs, alcohol, and suicide. Thank G-d Judaism guides us toward continual growth, faith, and optimism. We can make the decision to move past our pain and reach even higher levels of joy.

“You know, my savta, Rosa Shoshana Shefer, passed away three years ago. She was everything in the world to me. She survived four years in the Nazi camps. She was literally superwoman. She was above This World. Before she passed away, she said, ‘Tamir, do you think that I don’t remember what happened to me and my family during the Holocaust? Of course, I do. I think about it every day. It’s in my brain, all day, every day, but I choose to be happy.’

“She went through so much tragedy in her life, so many setbacks, and still dedicated her entire life to happiness, choosing to be happy, and choosing to live an incredible life, always being there for everyone around her.”

Tamir holds the memory of his savta close as he continues to chart his path forward. He may not be running his favorite fast breaks or scoring points in the big leagues, but his goal has always been something far higher.

“When I stood up for Shabbos, when I kept on my yarmulke and tzitzis, I wasn’t playing just for me, but for Hashem,” he says. “So even when I had to stop playing, that didn’t mean my game was over. I could continue to pursue my dream in a spiritual way. My mission continues.”

Net Result

Swish!

The basketball drops through the net. Ho-hum. Regular stuff.

But how is this basketball suddenly different from all other basketballs? It’s just dropped through the Antimicrobial and Moisture Wicking Aviv Basketball Net, which cleans the ball from bacteria and sweat every time the ball passes through. It’s the latest innovation of Tamir Goodman, and it was born during a Covid lockdown.

During Covid, all of Tamir’s camps, clinics, training sessions, consulting, and scouting were closed. And then an email arrived, from a basketball organization he works for, saying that if training ever starts up again, each player would need to bring their own ball, to prevent the transmission of germs.

“My initial thought was, how can this get any worse? We can’t even pass a basketball anymore!” Tamir remembers. But then he got creative and started thinking, why don’t we utilize the instruments of the game itself to prevent the spread of germs? With that thought, the idea for the Aviv Net was born.

“If you’re like me and can’t even spell ‘science,’ I want you to know that all the things people say about you, the names they call you, or the stigmas you get stuck with — they’re hurtful, but they say nothing about you,” he says. “These people have no clue about the incredibly creative way you see things and all the unique ways that your brain works. So work with your creativity, unique perspective, and all your special strengths, and it will ultimately bring you extraordinary success!”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 907)

Oops! We could not locate your form.