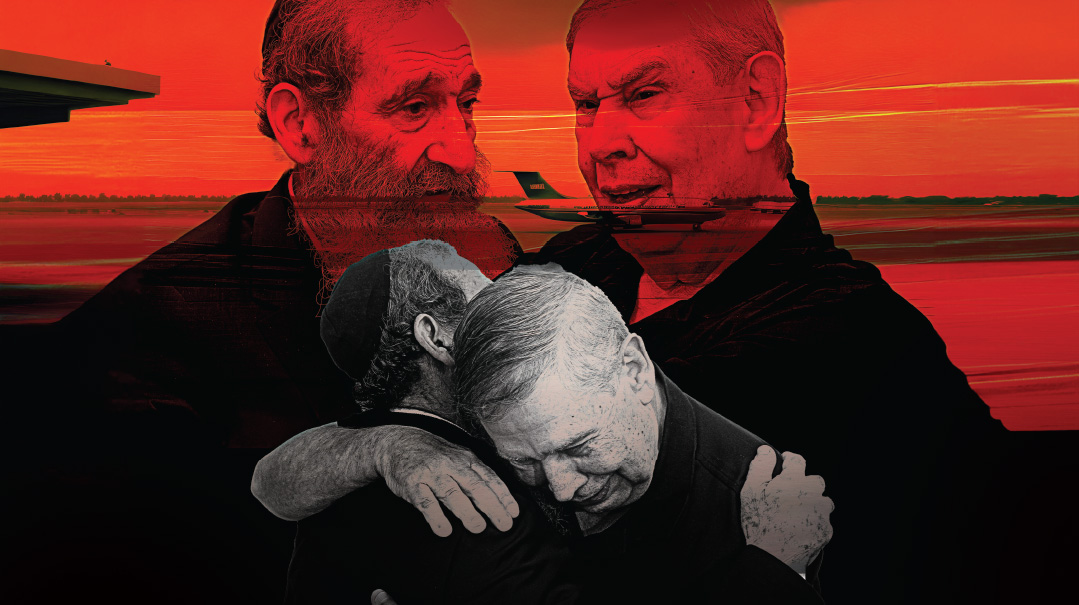

Neighborly Gifts

Rabbi Tzvi and Rivi Horvitz spread a welcome mat of spirit and sushi in Israel's most secular city

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Personal archives

When Rabbi Tzvi and Rivi Horvitz moved from Bnei Brak to the upscale, gentrified Tel Aviv neighborhood of Neve Tzedek, they were hoping to create an inclusive community shul where all types and stripes feel safe and comfortable. But they had no idea that their burgeoning kiruv kehillah would morph into a spiritual therapy center, where hundreds of massacre survivors would discover that food for the soul went way beyond a gourmet kiddush

It’s 1:00 a.m. on Leil Shabbos, and hundreds of survivors from the Simchas Torah slaughter at the Nova music festival are swaying in unison to the ancient haunting melody of Kah Echshof. Some are barefoot, others sport rainbow-shaded hair, tattoos, rings, and studs in assorted places from head to toe, but they all have one thing in common: These broken, traumatized young men and women who escaped with their lives after seeing their friends brutally murdered in front of their eyes, have come to keep Shabbos together as a first step in healing.

And that’s one reason Rabbi Tzvi Horvitz — who has been bringing massacre survivors and war refugees to his table for huge communal Shabbos meals over the last three months — is sure that his high-visibility kehillah, nestled in a trendy, upscale, and gentrified corner of Tel Aviv called Neve Tzedek, is more vital than ever.

This is the same Tel Aviv that saw the worst anti-religious demonstrations in Israel’s short history just a few weeks prior, when over a dozen public and private Yom Kippur services were disrupted by bazooka-blowing rioters and anarchists set to destroy organized (Jewish) religion in their city.

Yet after October 7, something major shifted — the mascot flags of the anarchists disappeared and the weekly anti-government/anti-religious demonstrations and disruptions suddenly dissipated. And that’s when Rabbi Horvitz and his wife Rivi — who’d transplanted themselves in Tel Aviv from Bnei Brak in 2018 — realized they were in the right place at the right time. Suddenly, they became a magnet for survivors of the doomed Nova music festival and for the displaced residents of the south living in hotels around the city. And what they’d created as a small kiruv shul morphed into a spiritual therapy center as well, with communal Shabbos meals for hundreds of people who discovered that food for the soul went way beyond the sushi platters they put out for the weekly kiddush.

For Rabbi Horvitz, an ordained rabbi, marital and family therapist, court-recognized mediator, and certified life-coach, this new role was the perfect fit.

T

he inclusive kehillah is called “Chasalat” — officially an acronym for all the types who gravitate here: “chareidi, chiloni, chassidi, Sephardi, Lita’i, Teimani” — but it’s also a play on words of the famed Israeli bug-free salad brand. Because this Torah-observant congregation really is a “salad” — one big family of all types and stripes, creating a new narrative on the polarized Tel Aviv streets.

Many of the kehillah’s regulars are what are known in Israel as “chozrim b’she’eilah” — those who grew up in Orthodox Israeli families but have rejected organized Judaism; there are also lots of French, British, and American olim and resident tourists, and there are the who’s who of the Tel Aviv cultural scene — including CEOs of well-known companies, actors, and media personalities — who have moved into the charming homes lining these few blocks of cobblestoned alleyways.

Some come to Chasalat for the energetic, dance- and song-infused Shabbos prayers; others skip all that and just show for the elaborate weekly kiddush. But whoever they are, everyone here knows that they’re safe from comments about their garb or hair fashion, or from snide remarks toward those who’ve actually chosen to wear a kippah and tzitzis — everyone can come however their self-expression pulls them when they wake up that morning.

“They’re looking for a place where they can have some connection to Yiddishkeit, even if many of them have rejected the formal structure,” says Rabbi Horvitz of his five-year-old congregation that has somehow become the Shabbos happening place in this hub of Tel Aviv culture.

“These guys put me in a real pickle,” says Tal, who owns a boutique on breezy Shabazi Street nearby. “I thought I hated dati’im, but you can’t help liking the rabbi and his group. I guess I just knew the stereotypes, but these people have style. You should see the grill boards and boutique wines they put out at the kiddush.”

Tal, like so many of his fellow Tel Avivians, grew up with an underlying sense that the religious people in the city are interlopers, unwelcome in this great secular stronghold (although a few minutes away from the iconic Habima Theatre and Dizengoff Center are the now-defunct shtibels of Modzhitz, Stolin, Ger, Ozherov, Belz, Koidenov, and several others). Yet over the last decade or so, Tel Aviv has become noticeably more religious again. You don’t see many shtreimels here anymore, but religious people seem to be everywhere.

“The old secular elites feel sociologically besieged,” according to historian and commentator Dr. Gadi Taub in a piece in Tablet magazine. “They look at the demographics, at the religious populations growing rapidly. These elites feel that Israel is their country and sense that they are losing ground. They fear that all the barbarians, the unenlightened hordes of messianists, Mizrachim, and traditionalists will impose a Middle Ages theocracy and that their own future is doomed.”

But somehow, Rabbi Horvitz’s shul has been immune to the animosity. While anarchists and anti-religious rioters were busy disrupting prayer services around Tel Aviv this past Yom Kippur, on Yom Kippur night, the Chasalat shul — which had recently moved from an outdoor park minyan to the dining room of a nearby Ulpana girls’ high school — was packed. Even the school’s vending machines were cleaned out (many attendees either didn’t know or didn’t care about fasting or purchasing snacks, but they still showed up for a Jewish experience).

How did Rabbi Horvitz escape the fate of Rosh Yehudi founder Rabbi Yisrael Zeira, rescued by police from a near-lynch by far-left anarchists who’d targeted the organization’s free public Yom Tov prayers in Tel Aviv’s Dizengoff Square?

“It’s true that after Rosh Hashanah this year the tensions rose to unprecedented levels and Yom Kippur was targeted all over the city, but I think we escaped it because really, I’m just a neighbor. I have no organization backing me, and they don’t see me as an aggressive religious interloper,” Rabbi Horvitz says. “Sure, we’ve been harassed over the years with noise and attempted disruptions, but even though some locals might scream, curse, and blow their bazookas during our services, we don’t react. I try not to add any fuel to the fire.”

W

ith his gift of oratory, sense of humor, outgoing personality, and boundless energy, Tzvi Horvitz always had a sense that he would one day create something beyond the insulated streets and batei medrash of Bnei Brak where he grew up. While the gedolim of the town had always been his role models — his grandfather was a chavrusa of the Steipler Gaon (Reb Tzvi actually has the Steipler’s kittel and wears it on Yom Kippur) and Reb Tzvi himself had an open door to Rav Chaim Kanievsky — after learning in Yeshiva Ateres Yisrael and Mir, he traveled to the US and spent three years in Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin, where he established a close relationship with Rosh Yeshivah Rav Aharon Schechter and even learned with him b’chavrusa.

It was the Rosh Yeshivah who first spotted Tzvi Horvitz’s kiruv-work potential, sending him off to connect with the masses of Israelis who’d traveled to the US in search of their pot of gold.

“We started what was to become a prelude to Partners in Torah,” Rabbi Horwitz recalls. “This was 20-some years ago. We started chavrusas over the telephone, and it wasn’t long before my friends and I had hundreds of calls every day. We’d find people in all sorts of ways. I once went to a revival retreat together with Rav Amnon Yitzchok and cold-called the people who left their phone numbers on his list. I was once leaving my calling post to go daven Minchah, when the Novominsker Rebbe saw me and said, ‘What, you’re leaving a d’oraisa for a d’rabbanan?’ That gave me a real push. I knew I’d have to do something for the klal.”

Reb Tzvi came back to Eretz Yisrael, married Rivi Dvorkas, and settled in Bnei Brak. That was the base from where he went out to give shiurim and kiruv lectures in various venues (including the stock exchange and diamond bourse). He also spent over a dozen years serving as a prison chaplain in Ayalon and Maasiyahu prisons, where he was exposed to the seedy underbelly of Israel’s crime world and learned how the Jewish heart can beat in the most hardened felons.

He mentions one fellow he’s still in contact with, a formal regional Mafia operative who was in charge of collecting protection money payments in Holon and Bat Yam. “He got into big trouble after killing four Arabs who tried to steal his car, and was serving several consecutive life sentences,” Reb Tzvi relates. “But we became friends — every time I’d come to give a shiur, he would set up my chair. Eventually he started pulling his life together. Now he has a long beard, learns Torah every day, and is in a prison halfway house. We’re still in close contact — and he gave me my first lesson in never giving up on anyone.”

T

he Horvitzes had been living in Bnei Brak for years, but felt the time had come to look into new frontiers. “We had a large, comfortable apartment, but we never considered it our permanent home. We always felt it was temporary,” says Rivi, an accountant and senior manager at the First International Bank in Tel Aviv, who’s been following her husband along on his journey (“After living with him for so many years, it totally rubbed off”), and is a teacher of Jewish Family halachos to secular brides.

“Rav Chaim Kanievsky always pushed me to move out of Bnei Brak,” Reb Tzvi says. “He kept telling me, ‘You’ll soon find your place, the place where you can be mashpia.’ And it happened. In 2018, when our twin girls were five, one of them had to be hospitalized on Erev Yom Kippur, and I realized I’d be in Ichilov Hospital for Yom Kippur. I entered the hospital’s shul before Kol Nidrei and was in shock. There were around 300 people there, some with machzors, others with nothing but their IV poles — but there was no chazzan. There had been some coordination mishap between the would-be baal tefillah and the hospital’s rav, but meanwhile, hundreds of people were standing around, waiting for someone to start Kol Nidrei. So without any choice, I went up and banged on the bimah and started aha, aha, ahaaa….

“I was the chazzan and baal korei from Kol Nidrei through Neilah. There was a fellow there, around 60, who was diagnosed with terminal cancer,” Reb Tzvi continues. “He told me he hadn’t been religious since he was a teenager, that ‘Hashem and me, we haven’t been friends in decades.’ But now the doctors told him he had two months to live, so he decided he’d pray one last tefillah. ‘I waited around, but no one was going to the amud,’ he told me, ‘so I told Hashem, “if I finally decide to pray to You and there’s no chazzan, then I’m going home.” As soon as I said that, you showed up, banged on the bimah, and started davening.’ He lived a year after that, and merited to go into Rav Chaim with me before he died.”

Meanwhile, Reb Tzvi was continuing to nurture his dream of creating the type of communal structure in which even a staunch secularist would feel comfortable. “Outside of Eretz Yisrael, I saw a real thirst for community, even in the non-religious sectors. People aren’t embarrassed to want to be part of something Jewish. Here, especially in Tel Aviv, no die-hard secularist wants to admit that he wants to be part of some Jewish structure, something bigger and more encompassing than his own private life. I wanted to give Tel Avivians the concept of community, to make even the most avowed secularist want to join something Jewish and not be embarrassed about it.”

During those weeks, Reb Tzvi and Rivi were taking a walk through the Neve Tzedek neighborhood, once a slum of poor Yemenite immigrants and today one of the most exclusive and expensive parts of the city — an oasis of a few short square blocks of cobblestones and restaurants and trees and private homes abutting the Shalom Tower and the hustle and bustle of the pulsating city.

Built in 1887, Neve Tzedek was the first Jewish neighborhood outside of the old port city of Jaffa, today just a 15-minute walk away, but back then an ankle-deep trek through sand dunes and mud. Eventually, like most of south Tel Aviv, the buildings fell into neglect after the wealthier residents moved north, and became a run-down immigrant slum. Many of the buildings wound up on preservation lists though, so instead of demolishing the neighborhood and constructing hi-rise apartments, restoration work began. The gentrified neighborhood has become an upscale cocoon and a real estate and cultural hotspot.

“Maybe this can be our place?” thought Rivi out loud. “It’s lovely, quiet, very close to where I work. It’s like a magical island in the middle of a bustling metropolis.”

Rav Chaim Kanievsky seemed to concur. After Reb Tzvi described to him that Yom Kippur in Ichilov, Rav Chaim said, “Now you’ve found your place.”

T

he Horvitzes’ first apartment was a tiny rental for an exorbitant price that was totally out of their range, yet that’s when they saw the first glimmer of siyata d’Shmaya. When the owner met Reb Tzvi, he looked at him and said, “Hey, I know you from TV — you’re on TV, right? For you, I’ll cut the price in half.” It turned out that the owner was a regular watcher of Hidabroot, the kiruv channel run by Rabbi Zamir Cohen, where Reb Tzvi has a weekly slot.

But what did people think when they saw a chareidi family moving into their territory? “Well, aside from the last remaining Yemenites, the neighbors were pretty surprised to see a religious family on the block,” says Rabbi Horvitz. “There had been dozens of shuls here at one time, some of them just tiny one-room shtibels, and they told us about one small shul that hadn’t been used in years that we could have if we wanted.”

In the beginning, their little congregation consisted of Reb Tzvi, Rivi, and their three children, who were enrolled in chareidi schools across town. They were doing this totally on their own, with Rav Chaim’s blessing.

“Our families thought we’d gone nuts, and we were even embarrassed to host them in our new home,” says Rivi. “We traded our beautiful 180-meter apartment in Bnei Brak for a dingy, decrepit, overpriced hole with the washing machine in the middle of the living room, but we had a vision: We wanted to be the gamechangers, to establish a precedent that a chareidi family can come into such a neighborhood and create an all-encompassing kehillah. (They eventually moved into a small but lovely, efficiently-designed apartment on Shlomo Molcho Street, surrounded by trees and flower beds.)

“And if you know my husband, you know that he never turns down a challenge. So when one friend told him, ‘Neve Tzedek? You’ll never make it there — it’s the last place on earth to do kiruv,’ that clinched it.”

They had one caveat, though, which they’ve continued to maintain from the beginning: With all the different types of people who come to the shul, to the kiddush, and to the communal meals, in their own home they have strict control over the guest list.

“Our kids come to shul and see all types of Jews, but our home is our fortress, and we want our children to be protected and feel a certain safety that within the walls of the home, it is insulated and protected,” Reb Tzvi says. (On their recent big Shabbos for Nova survivors, the children weren’t there. Sefi, their yeshivah bochur son, spent Shabbos in yeshivah and the twins went to Riva’s brother in Kiryat Sefer. “They’ve seen a lot,” says Reb Tzvi, “but this was not for them.”)

They were slowly building up the minyan in the little shul, but less than a year later, Covid hit, and indoor minyanim were closed down. For the Horvitzes, it was a blessing, because they moved the minyan to a garden park on Pines Street, and the neighbors started to notice.

“This is very secular/leftist territory, so the neighborhood didn’t really know how to deal with this very public minyan,” says Rabbi Horvitz. “So we bought hundreds of elegant gift packages of chocolates and knocked on doors: ‘Hi, we’re new here in the neighborhood, maybe you’d like to join us for an unpressured tefillah or Jewish experience?’ We were able to convey the feeling that we’re not out to brainwash anyone, we’re just one of the neighbors.”

During regular times those neighbors might have been suspicious and resentful, but because it was during Covid, everyone was feeling so isolated that the park felt welcoming.

It wasn’t long before they had around 100 people joining in on Shabbos morning.

“Granted, maybe not all of then davened, and a lot of them were waiting around for the elaborate weekly kiddush, but they were present,” Reb Tzvi says. But there were also the neighborhood antagonists. “There was one fellow who grew up chareidi but was now super-anti. He bought a special amplification system and installed it on his porch to ‘welcome’ us. As soon as we started davening, we heard the boom boom boom from his music. People were angry, they all wanted to scream at him, but I told them not to comment, that it takes two to fight.

“On Sunday, I wrote him a note. ‘Shalom, so sorry we disturbed you on your day of rest, but what can we do, these are the Covid regulations, hope this will all be over soon. Best regards…’ For the next few weeks, he kept making noise, but about a month later, he actually decided to come to shul — but not before he finished testing me. He purchased a coffee for me on Shabbos morning, and brought it into shul as a ‘gift’ to me. He comes from a frum home and he was testing my reaction — he knew I wouldn’t use something he just purchased. I took it, thanked him so much, put it down, and continued to daven… Well, to make a long story short, the following year I officiated at his wedding, right here in the park. To a woman who was coming closer to Torah.”

Reb Tzvi shares the story, then imitates Rav Yisrael Meir Lau’s thick, unmistakable rabbinic inflection as he shares the precious piece of advice Rav Lau imparted: “Teidah lecha HaRav Horvitz, rav b’Bnei Brak tzarich ladaat mah lomar, rav b’Tel Aviv tzarich ladaat mah lo lomar [a rav in Bnei Brak has to know what to say, while a rav in Tel Aviv has to know what not to say].”

He’s shared that lesson with his neighborhood friend Moshe, an elderly fellow who comes regularly to Chasalat and always asks questions about the weekly parshah. “Last summer, on parshas Korach, Moshe noted that in several places around the country, there have been sinkholes that have opened up, and just that week, the ground opened up in the parking lot of Shaare Zedek hospital in Jerusalem, just like the earth that swallowed up Korach and his associates.

“‘Kevod HaRav, what’s the big deal about Korach’s punishment, if we see it happening every day?’ he asked me. I told him, ‘The ground “opening its mouth” happens all over, but the miracle with Korach is that afterward, it closed. And Moshe, it’s the same with us. Everyone can open their mouth, but the chochmah is to close it afterward. If we would learn when to keep our mouths shut, we would bring the Geulah.’”

K

nowing what not to say is part of the kehillah’s draw for those who’ve had many comments come their way, brought upon themselves or not.

Rivi shares how, one Rosh Hashanah, a bleach-blond fashionista in the latest Tel Aviv style came to the park and sat down on a bench. “I went up to her, told her Shalom, and then she asks me, ‘What seminary did you learn in? Because I learned in Wolf in Bnei Brak…’”

“It turns out she’s from a very chashuv chareidi family, was married with two kids, and then decided to leave it all,” says Reb Tzvi. “But she decided to stay for the tefillah, and then at Mussaf, she pulls out her phone and starts to film. Now, it’s true that there are a lot of curious onlookers who do film on Shabbos, what can you do? But right in the middle of Mussaf while I’m at the amud, she sticks the phone in my face to film me as the chazzan. She sticks the camera on my right side, I turn to the left, she moves to the left, I pull the tallis over my head.

“It made a huge impression. She’s a real provocateur, and she later told us that she always makes a little disruption, they tell her it’s not appropriate and she leaves in righteous indignation, telling herself, ‘You see, there’s no place for me.’ But here we met her with total acceptance — we didn’t give her a chance to be unwanted.

“And then, Erev Yom Kippur, I get a call from a rosh yeshivah and rosh kollel in Bnei Brak. He told me, ‘Thank you so much, I have no words — my daughter hasn’t spoken to me in two decades, and now, in your zechus she finally contacted me.’ She runs an organization for young people who’ve left religion, and now she started bringing some of them to our shul. She hasn’t become a baal teshuvah, but we broke through the ‘anti.’”

Then there was the time someone came to Reb Tzvi on Shabbos morning and told him that a chassid had been spotted in a restaurant eating treif.

“I went to the restaurant, tallis and all, and sat down next to him,” Reb Tzvi remembers. “It turns out he went with his wife to her parents, they got into a big fight about the level of his religious observance, he left his wife with her parents, took his car, and drove to Tel Aviv on Shabbos, shtreimel and all.

“He takes one look at me and says, ‘What are you doing here?’ I told him, ‘I can ask you the same question but I won’t. I will tell you that Hashem sent me here to help you.’ ‘I don’t need your help. Get out of here…’

“‘You know what I like about you?’ I ask him. ‘You’re honest. Do you know how much Hashem loves people who are really honest with themselves? Can I give you a hug?’ So I give him a hug, and he puts his cigarette out. Then, in the middle of the restaurant, I start singing Yosef Chaim Shwekey’s ‘Chazor becha ben adam chazor becha…’ He started crying in the middle of the restaurant, and I took him home with me.

“We try to give all these people an anchor, a place where they can connect to the spark of Yiddishkeit that never gets erased.”

Not far away from Chasalat is a Conservative (“Masorti”) synagogue, but over 20 families from there have quietly migrated over to Reb Tzvi’s minyan.

Some of the “Kaplan Force” demonstrators — the anti-government protesters whose headquarters was on Kaplan Street — would even come around on Shabbos afternoon, together with their flags, before heading off to the weekly riots (they’d leave the flags on the ground outside). One well-known demonstrator would regularly show up for Minchah together with his flag, but told Rabbi Horvitz, “Sorry, Rabbi, I can’t stay for Havdalah. The demonstration is already starting and I need to be there.”

Rabbi Horvitz looks at these “anti” people who come to shul for the first time as diamonds in the rough. “Really, the connection he has with Hashem is so strong, because Hashem is really giving him the most attention,” he explains. “It’s like in a family, it’s the biggest troublemaker who gets the most attention. So when I see him coming into shul for the first time, my job is to make sure he has a positive experience, that he enjoys it, that he feels it’s a safe place, not a place where he feels he doesn’t belong. You know, I once heard from a big mekarev, ‘There are so many people out there desecrating Hashem’s name, doing so many spiteful things, distancing themselves so much. If I had two hearts, I would surely hate with one and love my fellow Jew with the other. But what can I do, I only have one heart.’”

K

ehillat Chasalat spent two years in the small park, rain or shine, but with the overflow to the surrounding streets, they were offered to use the dining room of the Uplana girls’ high school over on the next block, where they now hold Friday night and Shabbos day tefillos.

Rabbi Horvitz recently obtained permission to use the old Heichal Hatalmud building, a long-standing neighborhood shul that’s been out of public use for the last 30 years (and where his own grandfather gave shiurim for two decades). With help from the kehillah and private funds, renovations of the historic shul are underway. Rabbi Horvitz currently runs the kehillah’s daily Shacharis minyan there.

And then came the massacre, and the war, and the survivors.

“After October 7, we decided that we need to expand our shul, to make a movement. We knew that there are thousands of people out there that can use what we have,” says Rabbi Horvitz.

Since then, good people affiliated with the kehillah have sponsored joint Shabbos meals for hundreds of people — for the survivors of the Nova festival and for the refugees in the hotels around Tel Aviv. In one of the hotels, Rabbi Horvitz initially accessed 50 rooms for the Nova survivors — broken souls who’ve had it hard dealing with life in regular times, and now saw their friends slaughtered before their eyes — and that started a regular, ongoing program for them.

“Many of these young people are from frum families, and that first Shabbos, we had 250 people of all types — barefoot, tattooed, piercings. After going through cases of good wine, we had an Oneg Shabbos, and the people didn’t want to stop singing. There was a group of girls, full of piercings and weird haircuts, who knew all the words to the zemiros without a siddur.

Sar (Sar Shalom) Yosef is one of the new regulars, having made his way to the first Shabbos program after hearing from friends that a certain rabbi in Tel Aviv wanted to invite them.

“I grew up in Jerusalem in a chareidi family, but left religion when I was a teenager,” he says. “I hated the pressure.” Sar wasn’t so into the music, but he was doing a big business at the Nova, two food concessions and a team of workers. He doesn’t really know how he survived when people were being picked off by terrorists all around him, including his workers — all he knows is that he kept running and didn’t look back.

“I heard the screams, the shrieks, people being attacked and slaughtered, but I didn’t turn around,” Sar relates. “I didn’t see anything. I just kept my eyes focused in front of me. There were others with me who turned around, but I didn’t. I had served in the army — I know the sounds of terror, of murder. I didn’t need to see it behind me.”

He was on a Nova survivors’ retreat when Rabbi Horvitz located them. “It was so special of him, because it gave us an opportunity to stay together and start to heal,” he says. “Today, I want to keep Shabbat, but you know, it’s not so easy on your own. So it’s really great that we have this whole chevreh, we’re all here together. Here I keep all of Shabbat, and it’s really a kef to do it right — since we’re all together, it gives us koach and we support each other. Right away I started again with a kippah, tzitzit, tefillin, Shabbat. I don’t touch my phone on Shabbat, don’t travel. I still have a problem with smoking, especially if I know it will help calm me down and make me feel better, and if I’m alone it’s hard not to, so I’ve also had nefilot. But you know, when I’m with the Rav, even half a cigarette I won’t light up.”

When you’ve seen death up close and you escaped its clutches, what does that do to you? What does it do to you knowing that you wake up in the morning with the realization that Hashem saved me, and not my friends? How do you look at the day in front of you?

Sar says that some of his friends feel they have to make life better, that they’ve been saved in order to bring new purpose to their lives and to the world. But for him, it’s a different feeling.

“I’ll tell you the truth, it makes me feel like the people killed were tzaddikim and I’m still a rasha. They finished their tikkun, their mission in this world, and I still have a long way to go. Most people probably don’t feel that way, but I grew up in a home where my father was always learning Kabbalah, talking to us about the world of the neshamot.”

F

or Rabbi Horvitz, these gatherings — emphasizing G-d’s unconditional love, compassion, the power of prayer and resilience in the face of adversity — are tools to help survivors find strength and hope as they navigate a host of complex emotions and try to restore a shattered sense of security and well-being as they move toward healing and rebuilding their lives.

“Survivor’s guilt is a complex and challenging emotional response,” he says, “especially for those who’ve witnessed the deaths of their friends in such a brutal way. Most of the young people we’re in touch with are in therapy, but we see the huge benefits of having a strong support network of fellow survivors in order to provide validation and reduce isolation, and connecting with a spiritual or religious community.”

After the first Shabbos, when dozens of participants spontaneously decided to leave their phones in the hall and pick them up after Havdalah, Rabbi Horvitz knew he was onto something bigger than he could have imagined.

He says the first thing to understand is that a “mesibat teva,” these nature parties, are populated by people who are in an existential conflict. A person who wants to be poreik ol, to thrust himself into such a depraved environment devoid of all personal responsibility, he could go to a nightclub in Tel Aviv, so why does he choose a nature party? Because these people — either those formerly religious or who were never religious but want a type of spiritual adventure — have a strong spiritual pull, but don’t know where to put it.

“One girl whose boyfriend was killed told us, ‘I know nothing. I never heard of Shema Yisrael. I would want to learn a bit of Yahadut to try to make sense of everything.’ Another young man told me, ‘HaRav, you have no idea what it’s like to be in a drugged stupor and see a bunch of terrorists firing RPGs at you — you don’t know if it’s real or if you’re tripping out. Suddenly my friend right next to me is covered in blood. It took me time to figure out what we actually went through. I’m on sleeping pills for two months. On one hand, I’m asking myself, why was I saved? What does Hashem want from me? But I don’t love Him. I ran away from everything that would remind me of Him. And now He’s again trying to weasel His way into my life? He won’t let me sleep, He won’t let me eat… Hashem saved me for a reason, but I don’t want it — I don’t want to be dati!’

“This person is in deep conflict. So when he comes to us, he feels it’s a safe place. Here we try to understand, we bring in therapists, but we also address the very real questions of faith that so many of them have, after seeing their friends slaughtered and asking themselves very basic questions that a therapist alone can’t help them with. Because their crisis is not only emotional, but also spiritual.

“But you know, since October 7, it’s not just the displaced refugees and the survivors, but the entire nation is thirsting to latch on to some kind of meaningful spirituality — there is, like the Navi says, a thirst and hunger for devar Hashem. And it’s the obligation of each of us to come out of our comfort zone and be there for whoever needs it, from any place we’re in, even if we don’t live in Tel Aviv. We can’t say, ‘Our hands didn’t spill this blood’ — because if it won’t be us, they’ll look for it in some other place, either in India, or down the block in the Mesorati Center, or in the myriad other places that are waiting with open arms.”

But don’t be scared off. From Rabbi Horvitz’s experience, today the new “in” trend is to be a maamin. “It’s no longer embarrassing to say you believe in Hashem, you love Hashem, and you want Mashiach. People have reached their rock bottom, and it feels so much healthier to say, ‘I’m a maamin’ than to hide behind hostility and hate.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 995)

Oops! We could not locate your form.