Mind the Gap

My job was to make sure Chana was getting proper nutrition, and I felt I was failing her

As told to Faigy Peritzman

Chana, my second child, was born on a Friday morning. As Shabbos approached, my husband went back home to be with my older daughter, planning on returning the next morning after he named the baby in shul. I settled in to spend Shabbos in the hospital, so grateful to Hashem for all the blessings in my life.

Our little Chana began having prolonged screaming episodes that very first night. By the time she was three days old, I’d already booked our first appointment with Prissy, a lactation consultant. My older daughter had been a difficult eater who refused a bottle, and I wanted to do it “right” this time around for Chana.

Yet Chana just couldn’t seem to get the hang of nursing. She choked, gagged, sputtered, and screamed when she was nursing. Chana was evaluated by an ENT who snipped both her lip-tie and tongue-tie when she was six days old, but the feedings didn’t improve. She would try so hard to nurse but screamed after almost every gulp. She needed to be burped after every successful swallow, and often sounded like a tiny bomb was detonating deep in her belly. She was clearly swallowing air, but from where?

Over the next three weeks, I visited the lactation consultant twice a week, trying every bottle, nursing position, and trick that she had up her sleeve. Prissy was very professional and had lots of experience, so I was hopeful that she would find the secret approach that would get Chana to nurse successfully. So far, the only way I could nurse her without her gagging and screaming was if she was lying flat on her back with her head tilted upward at an extreme angle. It seemed crazy that this was the only thing that was semi-helping. Prissy sent us back to have the lip-tie redone, but there was still no improvement.

Feeding Chana was very stressful. My job was to make sure Chana was getting proper nutrition, and I felt I was failing her.

Our pediatrician put her on Pepcid for reflux. It didn’t help.

During one of our visits, Prissy professed skepticism that Chana literally needed to burp after every swallow. But when Chana couldn’t gulp down an ounce without a burp in Prissy’s office, she believed it.

Finally, after another frustrating session, Prissy threw up her hands and said, “Y’all better pray!” I left her office feeling very dejected and forlorn.

Miraculously, Chana was gaining weight, but it took nearly two hours to feed her. I timed it once: For every two hours of “feeding,” she drank for only about 11 minutes. And nursing her was terrifying. She would gasp and choke, her eyes would water, and her face would turn red as she stopped breathing. Then she’d kick and flail until she’d finally swallow with a gulp and catch her breath again. I developed a mantra that I whispered as I fed her, “Breathe, breathe, breathe!” On a few occasions, she even turned purple in the face before she managed to cough and breathe again.

Bottles weren’t the solution either. Occasionally she’d take a few ounces from my husband when he fed her, but I never managed to bottle-feed her.

At this point, my six-week maternity leave was up, and it was time for me to go back to work. I was feeling great, but I had a baby who couldn’t drink normally! Thankfully my husband was working remotely from home at the time. I’d run home during my lunch break to try to feed her, and he’d attempt bottle-feeding the rest of the day. It was chaotic at best.

By eight weeks, with no improvement in feeding, we decided to have a swallow evaluation done to see if something was anatomically wrong with Chana, and booked an appointment with a pediatric hospital. To my amazement, at the initial evaluation appointment Chana drank several ounces of a bottle with very little trouble. I was shocked. It was the classic situation where problems vanish when you finally get to the doctor. (I’ll confess, I was so desperate at that point that for the next few days, I half-jokingly tried feeding her with the hat she wore at her evaluation, thinking maybe she’d take a few more ounces wearing her “lucky hat!”)

Not surprisingly, after seeing her eat so well, the clinician didn’t think anything was wrong, so I whipped out my phone where I had hours of footage of Chana’s choking, gagging, and screaming. Upon seeing that footage, the therapist ordered a swallow study pronto. I was so hopeful that the results of the test might tell us what was wrong with my poor, choking baby.

The next week we went for the swallow study. They added some contrast chemical to her bottle and performed a live X-ray of her as she drank. But the radiologist didn’t see anything noteworthy, other than that the milk went near Chana’s airway, but that she was able to clear it by coughing.

I went home in tears. If nothing was wrong with Chana, why did she choke at every swallow? Why could she only drink on her back? Why did she need to burp dozens of times every feeding? Wasn’t this indicative of a real issue? Yet several specialists had already told me everything was fine!

My mantra switched. Now every time I fed her, I whispered, “There’s nothing wrong with you!” Maybe I’d convince both Chana and myself.

Chana turned three months old on Pesach, and we traveled to the West Coast to spend Yom Tov with my family. My mother, a pediatrician, was shocked to see how bad Chana’s feeds really were.

She was so clearly hungry, but after a gulp of milk, would shriek, choke, and writhe in pain. The whole family took turns getting her many burps out. But the saddest part was that I wasn’t very empathetic towards my baby anymore. I told my mother that “The doctors said there’s nothing wrong. She’s fine, there’s nothing we can do.” I needed to believe that because otherwise… well, otherwise, what else could I do?

But my mother wasn’t convinced, and she arranged for me to have an appointment at an aerodigestive clinic, which deals with children with complex conditions of the upper airway, lungs, and upper digestive tract, including problems with feeding. I’d never heard of such a clinic before, but at this point, I really wanted Chana to show them just how much she choked and gagged, so I could receive some validation and real help. Let some doctor agree there was something wrong!

In the clinic, two senior ENTs and a resident attended to Chana. They put a scope down her nose to view the airway and esophagus. After the first swallow of milk, they all exclaimed, “Yup, there it is! Yes, there’s clearly penetration, yes, there’s the reflux, yes, it’s a cleft.” I had no clue what they were saying, and I was feeling quite hot and dizzy from holding my screaming baby on my lap while she had a camera down her nose.

The doctors continued talking, and after they left the room, I asked my mother to translate.

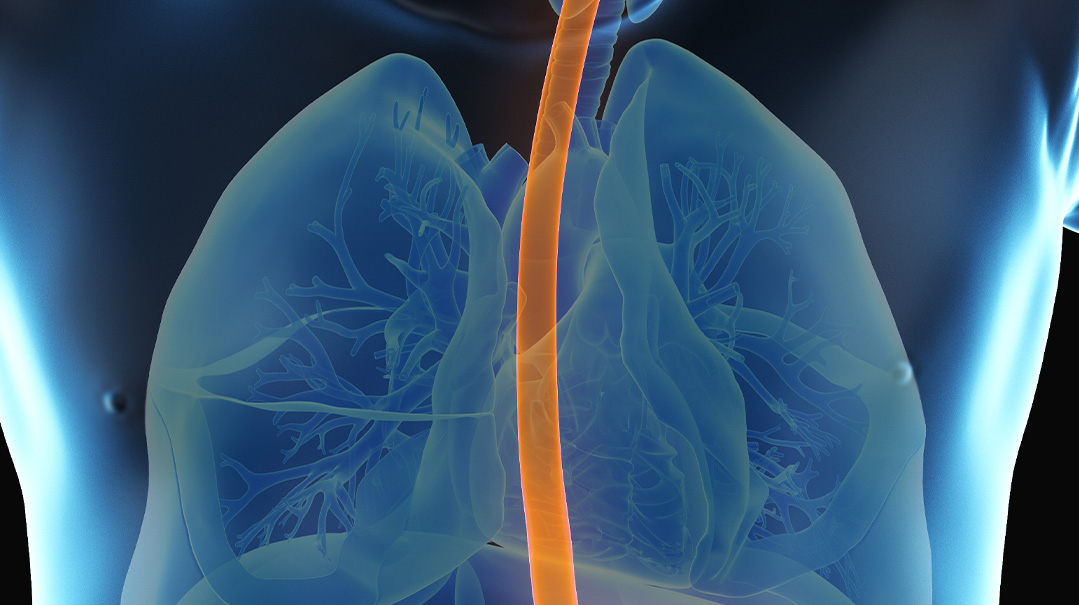

The doctors could see that Chana’s esophagus was very red and raw, aggravated by a lot of reflux. They also believed there was a notch, or laryngeal cleft, in her esophagus. In short, air was going down the food pipe, and milk was constantly irritating the airpipe, shutting her airway and making her choke. There was also the danger that milk could enter her lungs and cause all sorts of trouble. The official diagnosis was laryngeal cleft, Type I (see sidebar).

I couldn’t believe it! I’d spent so many hours nursing Chana and trying to convince myself that nothing was wrong, but there was something wrong with her all along.

In the past, a baby like Chana might’ve just been written off as colicky. But with modern technology, the problem was not only diagnosable but fixable! The doctors explained the process. Chana would undergo a small operation, in which some temporary putty would be injected into the cleft. Together with some stronger reflux medicine, this would actually solve the issue. In the meantime, the doctor prescribed a strong antacid for the reflux he saw on the scope and suggested we do the reparative surgery when we returned home.

Back at home, I contacted an ENT who dealt with laryngeal clefts. The earliest appointment was months away, longer than Chana had even been on this earth. I was so frustrated because now that I knew what the problem was, I wanted to have it corrected that very second. Still, the diagnosis helped me shift my approach toward feeding her. I was full of empathy, and my mantra became, “It’s okay, Chana, we’re going to help make you better!”

Finally, our appointment arrived, and the new ENT scoped Chana again, an unpleasant procedure. But to my dismay, he didn’t agree with the first ENT’s diagnosis, and wouldn’t schedule us for the procedure. He maintained that while Chana may have a cleft, it wasn’t large enough to warrant putting such a young baby under anaesthesia. He pointed out that time is often the best healer of children, and suggested that I try a different brand of bottles.

I was stunned and heartbroken. I’d thought we were almost at the end of this saga, and now he dashed those hopes. Instead, he scheduled a collaborative appointment with the pediatric GI and the hospital speech therapist to decide on a treatment plan that didn’t include surgery. I tried involving the original ENT from the West Coast who strongly advocated surgery, but we were tied to our insurance at home and had to follow their protocol.

A few weeks later, we had the meeting, and the takeaway was that we should schedule an upper GI scan. At this point Chana wasn’t choking or burping as much, thanks to her new antacid, and the results of the scan came back fine. The doctors regrouped and concluded that all was well, and the GI suggested that perhaps I should stay off dairy and soy. But the mommy in me knew that wasn’t the route to go.

Still, at this point, Chana really was doing much better, enough that I decided I wasn’t going to fight further for surgery. She was nearly 18 weeks old and at a great weight. Her feedings eventually went down from two hours to one, and then to 45 minutes. Clearly, the antacid medication was helping, and perhaps time was helping her grow out of her cleft as well. My motto became, “It’s okay, Chana, it’s all going to be okay. You’re doing great!”

Now, at ten months old, Chana is a delicious baby and crawling everywhere. She still can’t drink from a bottle and coughs quite often while she nurses on her back. But she’s starting to drink from a sippy cup and loves to eat baby food. I’m assuming the solids are easier for her now that she’s outgrowing the cleft.

I still wish we could have had the procedure done, though. Those months of frustration, and the struggle to feed my baby, were a tough situation to swallow. But I am so grateful to the Master Healer Who, in His great kindness, ultimately filled the gap.

What is a laryngeal cleft?

A laryngeal cleft (not to be confused with cleft palate or cleft lip) is a gap in the tissues between the larynx (the voice box) and the esophagus (the food pipe). This opening allows foods and liquids to enter the trachea (the airpipe), causing choking, wheezing, coughing, and respiratory problems.

Causes:

A laryngeal cleft is a rare congenital defect, meaning it develops spontaneously, usually within the first few months of pregnancy, and is present at birth. It affects 1 in 10,000-20,000 live births, more commonly in boys than girls. A laryngeal cleft can manifest on its own or as part of an underlying syndrome.

Signs and Symptoms:

Newborns with laryngeal clefts will most likely have eating issues. Because of the opening, food can enter the lungs, causing choking, wheezing, and coughing, especially during feeding.

If the respiratory issues become severe, the baby may present with cyanosis, a bluish skin tone.

Pneumonia and recurring lung infections may develop.

The baby may present with behavior and sleeping issues due to constant hunger.

Failure to thrive (not gaining weight or growing appropriately) are common.

Reflux is often present.

Diagnosis:

A laryngeal cleft is often diagnosed via a bronchoscopy and/or microlaryngoscopy in which a camera is inserted into the trachea and/or larynx and the cleft is seen.

Treatment

Laryngeal clefts are divided into four categories, depending on the size and location.

Type I:

This opening is above the larynx and often doesn’t cause significant problems. It can escape detection and can sometimes go away on its own.

Type II:

This opening extends below the vocal cords.

Type III:

This cleft is larger and extends beyond the voice box and into the airpipe.

Type IV:

This is the most severe form of laryngeal cleft, extending further down the airpipe. Typically Types II, III, and IV require surgical correction. Type I may only require medication to treat reflux and choking. If surgery is determined, the surgeon may decide to place a temporary filler in the area of the cleft. This filler generally remains in place for one to three months and afterward allows for the possibility of milder clefts to heal on their own. In some cases, the surgeon will use a laser to remove abnormal tissues in the cleft, then close the cleft opening with stitches. In more serious cases such as Type IV, the surgeon may need to perform an open surgery and repair the cleft through an opening in the neck.

There is no way to prevent a laryngeal cleft, but with proper treatment and care, prognosis for life is very good.

Information from the Cleveland Clinic

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 822)

Oops! We could not locate your form.