A Rare Scare

My daughter suffered a rare complication — again and again

As told to Faigy Peritzman

MY daughter Rikki is three years old. She’s a precocious, adorable kid.

She’s also been sent to the emergency room way too many times in her life, all because she has a unique medical condition no one had ever seen before.

It started when she was three months old. She had an ear infection that wouldn’t go away, so we started treating her with antibiotics. On the third day of her taking antibiotics, I picked her up from her crib to find she was shockingly cold.

I took her into my bed with me, but I couldn’t get her to warm up. Taking her temperature, I saw that it was below the threshold, at 35.5°C (95.9°F). She was also sleepy and completely out of it. I was very scared and ran to the kupat cholim. It was Friday morning (medical emergencies always seem to happen on Fridays), so my regular pediatrician wasn’t available. The doctor on call dismissed my concerns and told me Rikki was just recuperating from the ear infection.

Rikki is my youngest, and I have a houseful of kids. I knew this reaction wasn’t a normal one. I promptly made an appointment with a private pediatrician. This pediatrician took one look at Rikki and said, “This child is in shock. You’d better go straight to the ER.”

In the ER at Hadassah Hospital, they did blood work and started Rikki on an IV drip, thinking maybe she was dehydrated. She seemed to be doing better on the drip and was more awake, so after a few hours of IV, they declared it was fine to take her home.

But when I got home, I went to change her diaper and saw it was full of blood. I quickly called the ER and they told me to rush right back.

“It’s an Intussusception”

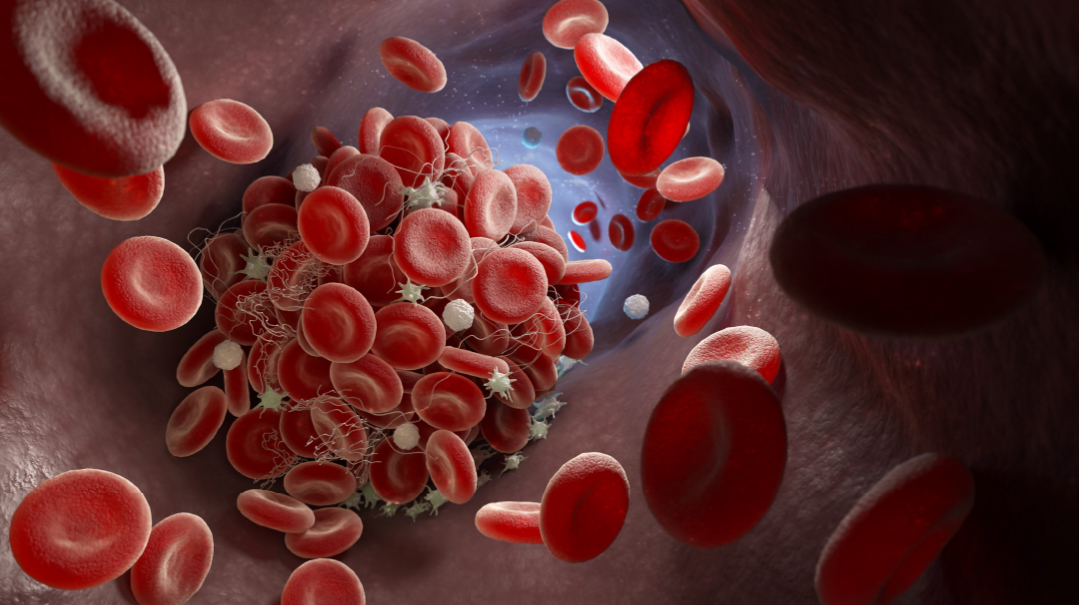

Back in the ER, they started running many tests, one of them an ultrasound of the intestines. On the ultrasound, they could see that Rikki had a intussusception: part of her small intestine was squeezed into her large intestine.

Intestines are made up of links, sort of like a line of sausages. Each link squeezes the food through and then releases it into the next link. What can happen is that sometimes a link doesn’t release itself and remains in a squeezed position, and then telescopes or slips into the next link, causing a blockage.

This blockage is very serious, because when the intestines are twisted around themselves, it cuts off blood flow, potentially killing those cells. Emergency surgery is often performed right away to remove the parts of the intestines that are blocked.

Thankfully, in Rikki’s case, they caught this just in time. The ER staff realized they were dealing with a situation where every minute counts. They put Rikki into a CT machine and then used air to pump through her intestines, essentially blowing them up so they would untwist themselves. B’chasdei Hashem, this process worked and her intestines returned to normal.

We stayed in the hospital for another two days just for follow-up, and when we left, we were sure the worst was behind us. While intussusception can occur in children, it doesn’t usually recur, so we chalked it up to a harrowing experience and went on with life.

A few months later, Rikki was sitting in her high chair when she suddenly violently threw up everything she had just eaten. I was shocked because she’d seemed fine before that, but I guessed she was getting a stomach flu. I took her out of the high chair and put her down to play and gave her a bottle of plain water. She sipped some water and then threw it up immediately. Ten minutes later, she started throwing up bright-green vomit.

I grabbed her and went straight to the ER.

The doctor in the ER made light of the situation, “She probably has a virus. There’s no medical diagnosis for bright-green vomit, it’s a myth of….”

While he was disputing my concerns, he started running an ultrasound and continued to talk… then suddenly got quiet.

Rikki had another intussusception, a blockage in a different part of her intestines. They quickly pumped her intestines full of air again and it opened. But six hours later, it got blocked again, and they had to reopen it.

Riki was in shock again, just like during that episode when she was three months old. Her body was icy cold, and she was lethargic, not moving, not interacting with anything around her.

This lasted a few days, but finally she reverted to her regular self, and we were able to go home.

The third time her intestines became blocked again was when she’d just turned a year old. She’d been fighting a virus, and then on Erev Rosh Hashanah, which was a three-day Yom Tov, I went into her room and couldn’t wake her up. She was freezing cold again, and her body was floppy and limp. My pediatrician works in the ER in Hadassah, so he told me to come in and he would put her on IV and run blood tests and make sure we’d be home in time for Yom Tov. It didn’t occur to him that this could possibly be another intussusception, because these things simply don’t recur so often.

Yet sure enough, when they ran the ultrasound in the ER, they could see another blockage. This time it wasn’t as much of an emergency. The past two times, her small intestine had telescoped into her large intestine, but this time, it was one part of her small intestine that had telescoped into another part within the small intestine. The hospital assured me that this type sorts itself out and we could go home.

But I was petrified to bring Rikki home in her condition. She hadn’t eaten in two days and was still limp and ill.

How could I be home over a three-day Yom Tov without any medical supervision?

“I’m not taking this baby home,” I announced to the staff. “You have to take care of her.”

To give them credit, they humored me. But they clearly thought I was being an overprotective mother. They put me in a room all the way at the end, farthest from the nurse’s station, and hooked Rikki up to IV. Later, I found out that this room was for kids who didn’t really need to be in the hospital, but whose parents wanted them there… I felt like a pariah.

Could It Be a Zebra?

Medical students are taught a concept from Dr. Theodore Woodward: “When you hear hoofbeats behind you, don’t expect to see a zebra.” It means they should assume the hoofbeats are from a more commonly found horse than an exotic zebra. According to the staff, my kid had a virus, was maybe a bit dehydrated, and, yeah, there was a mild intussusception, but all was fine, so why did I overreact and think there was something more going on? Yet even if the medical staff didn’t take me seriously, I knew Rikki’s past history and I wasn’t taking any chances. I spent the three-day Rosh Hashanah in the hospital still in my weekday clothes and with nothing I needed.

After Yom Tov, it was clear that Rikki was doing better, and we went home. As far as the hospital staff was concerned, that was the end of the story.

Except that a couple months later, around Chanukah time, I was changing her diaper and again I found it full of blood. This time my pediatrician realized there was something more serious going on with these recurring symptoms. In the hospital they did find another intussusception and were able to reopen it again. But they were very concerned (finally!). In general, intussusceptions don’t recur. In the rare situations where intussusceptions do recur, it happens in the same spot on the intestines, at what is called a lead point. If someone has a certain spot in the intestines that is susceptible to recurring intussusception, usually due to a polyp or tumor, they perform surgery to remove that section and the problem is taken care of.

But Rikki’s intussusceptions were always in different places along her intestines. The doctors were flummoxed by why she had so many intussusceptions in so many random spots.

They were determined to figure out the lead point of these blockages.

We were referred to Prof. Dan Turner, the head of the pediatric gastro department in Shaare Zedek hospital. He ordered a gastroscopy, a CT, and a Meckel’s scan. Sometimes, there is an internal stub left over from the umbilical cord from birth that doesn’t shrivel up, which can cause problems in the intestines. But they didn’t find any evidence of this in Rikki. They also ran a CT. In the CT machine, Rikki was awake, but she wasn’t allowed to move at all. They strapped her down tightly to keep her from moving, and she screamed the whole time. They kept sliding her in and out of the machine, taking different pictures, and I was helpless to comfort her as she screamed hysterically. It was traumatic for me and for her.

For the gastroscopy, they put her out with anesthesia and took biopsies of different parts of her intestines.

With all these tests, the only thing that showed up was that the red lymph nodes that line everyone’s intestines were slightly enlarged in Rikki’s.

The doctor who came to give me these findings was a pompous sort who liked everyone to know that he knew exactly what he was talking about. He spoke about the enlarged lymph nodes and said that this is generally a sign of a milk allergy. Since I was still nursing, he told me in no uncertain terms that I would have to watch my own diet to refrain from any milk products, and then Rikki would be fine — no problem. I tried to interrupt him a couple of times, but realized he just needed to say his piece. Finally, when he’d given me a whole pep talk about treatment for milk allergy, I told him that most of my family has lactose intolerance, and I never eat any milk products, and Rikki had never been exposed to milk in her life.

Hmm. That took the wind out of his sails. “Well, I think you should do an allergy test. That’s all this could be.”

So much for that. We meanwhile made an appointment to go back to Dr. Turner, but as with all appointments for head doctors, there was a long wait. Meanwhile, Rikki was getting older and was able to tell me what was bothering her. One Friday night she suddenly lay down on the couch and said, “My tummy hurts.” I looked at her and saw she was completely white.

I dashed with her to the ER, and this time I stated my piece with conviction. “This is a child with many recurring incidents of intussusception, and she now has a stomachache.”

The staff shifted into high gear and took us straight to the office of the doctor on shift. There was a patient in his office at that time, but they hustled him out and brought us in instead. They knew that these blockages are so crucial to catch in time. While I was glad to be getting such quick treatment, it was also scary to know that your condition is serious enough that even the ER staff is concerned.

They were able to open the blockage, but the whole staff now galvanized to figure out what could be the lead point that was causing so many intussusceptions. You also know you’re in trouble when the doctors do their rounds and instead of just the doctor on call, you have the head of the whole department there, plus a group of medical students, all trying to pinpoint what could be causing this. There was barely any room for me to stand there as they all encircled her bed. One by one they offered ideas of tests, but they were all tests we’d done already with no conclusive results.

At one point they thought her appendix was swollen, but then when they took another ultrasound, they saw that it wasn’t her appendix but the lymph nodes next to her appendix that were so swollen they were making her appendix misshapen. These lymph nodes seemed to always be in the background of each emergency situation, but why?

Specialist Care

We’d heard about a specialist in Shaare Zedek who had incredible success in diagnosing gastro illnesses using just an ultrasound machine. In general, patients have to undergo CTs, gastroscopies, biopsies, all things that Rikki had gone through, but this doctor was able to render a definitive diagnosis based on specialized ultrasound. People from all over the world came to Shaare Zedek to benefit from her diagnoses. Obviously therefore, there was a huge waiting list to get an appointment with her. But we felt this was the only way to go. There was no reason to subject Rikki to so many traumatic tests again when we’d done them all and had nothing to show for it. My pediatrician had gone to school with this specialist so he called her, and we made an appointment for nine months from then. But when it came time for the appointment, we found out that on that day the doctor herself was not running the tests; her student was. Our pediatrician advised us to wait. We needed the top doctor here to be able to solve this mystery.

And then Rikki had another intense stomachache. This time, instead of running to Hadassah like we always did, we ran to the Shaare Zedek ER. Once you’re in the ER, top specialists who are generally impossible to reach are suddenly available for testing. Rikki got an appointment right then for this special diagnostic ultrasound.

This doctor immediately diagnosed Rikki’s problem. There are red dots all along your intestines that are lymph nodes, and Rikki’s were enlarged, bigger than most people’s. We’d seen that ourselves from the gastroscopy. But what this doctor was able to determine was that these swollen lymph nodes were actually the lead point, the cause, of all those intussusceptions that Rikki kept getting.

Every time a person gets sick, the lymph nodes in the whole body swell. You can feel them under your jaw, etc. In Rikki’s case, whenever she got sick, those lymph nodes on her intestines swelled as well. But since they were too large to begin with, they now were large enough to cause a blockage in her intestines. And that was why there were intussusceptions in different places each time; depending on where the lymph nodes were most swollen, that’s where the blockage occurred.

So now we knew what the lead point was. But what to do about it? Dr. Turner said he had read about such a thing in medical literature, but in all his years as head of gastro in Shaare Zedek, he’d never come across a single case of it. So how to treat it?

Dr. Turner posted this question on a worldwide group of gastro specialists. Finally, he got an answer from one doctor who said he had one patient like that six years ago. He treated the patient with intense doses of steroids, and that solved the problem.

It was clear that Rikki’s condition was extremely rare. And it was scary to go into treatment based on the experience of one other patient from six years ago. The steroids used in that case were extremely strong, with intense side effects during treatment and also the possibility of permanent side effects.

We were in a quandary. How could we treat Rikki with these potentially harmful drugs without clear indications that this was proven to work? We did a lot of research, discussed this in depth with Dr. Turner and our pediatrician, and went to ask a serious sh’eilas chacham.

In the end, the consensus was that as long as Rikki was fine, we shouldn’t treat. If chas v’shalom she’d have a stomachache, we’d have to rush immediately to the hospital. But if we could keep her health status quo, there was a good chance she would outgrow this condition. Her intestines would grow as she got older, but the lymph nodes on the intestines would not. Therefore, when she was older, these lymph nodes would no longer be able to cause such blockages.

So that’s where we’re holding now. Rikki is an adorable, healthy toddler, and we do our best to keep her from getting sick. Her morah and the parents in her gan know that if any of their kids don’t feel well, they shouldn’t send them to gan, because it is risky for Rikki to catch any illness.

We’ve also stayed completely off milk at this point. Why rock any boats even if it’s not clear if a milk allergy could actually cause the swelling? Rikki herself is very vigilant about her condition. When one mother accidently sent in a dairy treat for Shabbos treat, Rikki on her own refused to eat it. “I don’t want my tummy to hurt,” she explained.

She’s been traumatized by the many hospital stays she’s had and the doctors who’ve had to hurt her in order to help her. She dislikes anyone in a white coat. My pediatrician graciously takes off his white coat when we visit the clinic, just to keep Rikki happy.

It’s been seven months since Rikki’s last hospital stay. Each day she remains healthy is another day of growth for her, another step that will hopefully take her to the day that she’ll grow out of this risk.

And in the meantime, I’m hypervigilant. I’ve learned to look out for zebras instead of horses, because in Rikki’s case, the zebras were there.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 889)

Oops! We could not locate your form.