Harvard Honors Hitler’s Henchman

| December 19, 2023Harvard University’s history of anti-Semitism goes back at least as far as the 1930s

Title: Harvard Honors Hitler’s Henchman

Location: Cambridge, Massachusetts

Document: The Jewish Advocate

Time: 1934

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

—Mark Twain

Harvard University’s history of anti-Semitism goes back at least as far as the 1930s. Then as now, the inaction of its president and faculty in the face of true evil would have disturbing repercussions. A Harvard grad would rise to the upper echelons of Nazi Germany.

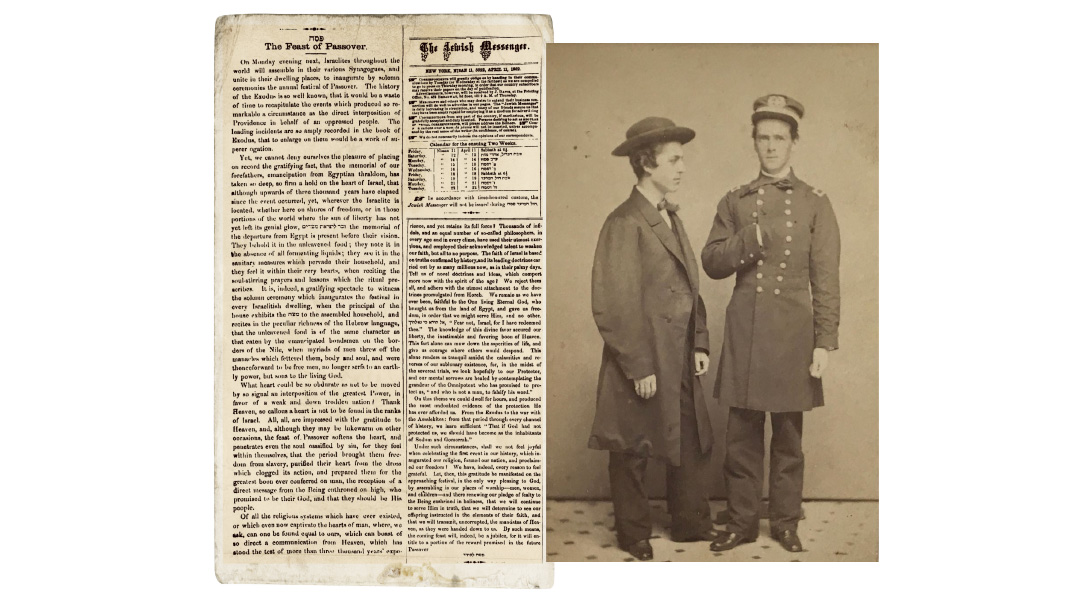

Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengl was born in 1887 in Munich, Germany. His father, Edgar, was a prominent art publisher, while his mother, Katharine, was the Boston-born daughter of William Heine, a Union officer in the Civil War (he was a cousin of legendary US Army General John Sedgwick).

Ernst Hanfstaengl was sent to America following high school to attend Harvard. Hanfstaengl’s charm, wit, and musical talents made him popular among the student body, most notably through his musical contributions to the Harvard football team, for which he played piano and composed fight songs that rallied crowds at games. Following graduation in 1909, he married and opened a branch of the family business in New York before returning to Munich in 1921.

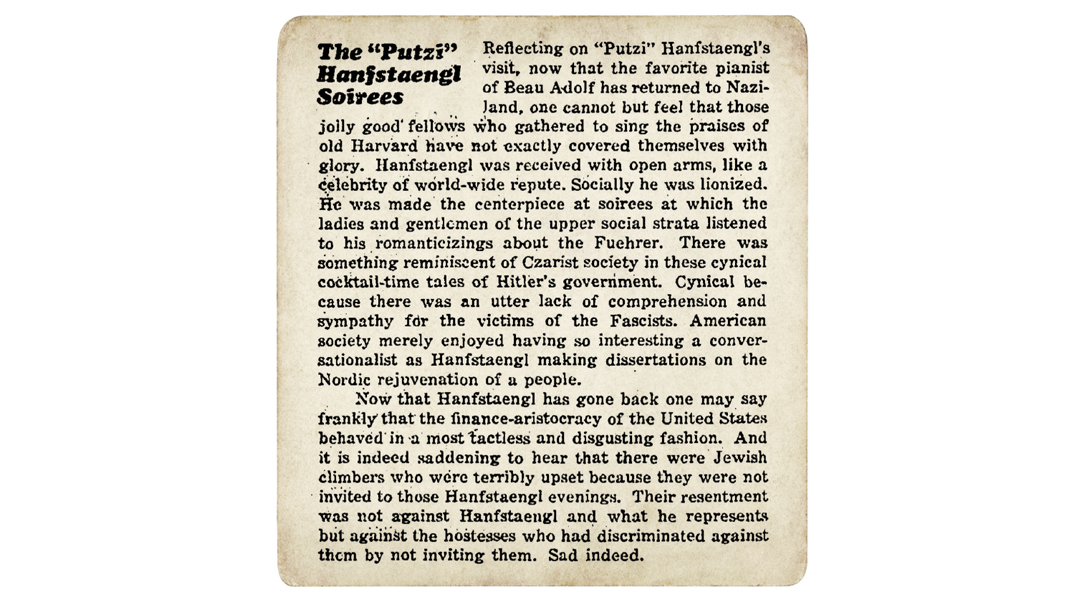

Hanfstaengl’s encounter with Hitler in a Munich beer hall in 1922 marked a pivotal turn in both of their lives. After attending his first Nazi rally, spellbound by Hitler’s oratory, Hanfstaengl declared, “What Hitler was able to do to a crowd in two-and-a-half hours will never be repeated for 10,000 years.” He helped finance the printing of Hitler’s Mein Kampf and crafted marching songs for the Brownshirts and Hitler Youth, drawing inspiration from his Harvard days. Hanfstaengl even claimed to have adapted the infamous “Sieg Heil” chant from cheers at Harvard football games. As the party’s foreign press chief, he represented the Führer to international media and was instrumental in shaping the image of the Third Reich abroad.

A firestorm erupted when Hanfstaengl was invited to a seat of honor at Harvard at his class’s 25th reunion in 1934. Hanfstaengl’s affiliation with the Nazis was well known, and Jews across America were enraged over the upcoming reception in his honor at his alma mater. Harvard president James B. Conant chose a path of polite engagement over confrontation, saying, “It is not a university’s function to incite political battles and fan the flames of international discord.”

Leading up to Hanfstaengl’s visit, an editorial in the Harvard Crimson suggested, “If Herr Hanfstaengl is to be received at all, it should be with the marks of honor appropriate to his high position in the government of a friendly country, which happens to be a great world power; that is, by conferring upon him an honorary degree.”

While the nationwide controversy led organizers of the event to downgrade the Nazi’s role to that of a mere participant, they made up for it by feting him around town like a celebrity, with prestigious alumni and President Conant hosting parties in his honor at their residences. In Conant’s autobiography published long after the Holocaust in 1970, the Harvard president defended his position by insisting that Hanfstaengl “had every right” to participate in the reunion.

Jewish students and other concerned individuals hung posters around campus to raise awareness of the Nazi being honored by Harvard. The signs proclaimed, “Drive the Nazi Butcher Out,” and suggested that the university bestow upon the visitor an honorary degree of “Doctor of Pogroms.” Following the Harvard administration’s instructions, campus police dutifully tore down the anti-Nazi signs wherever they appeared.

The festive atmosphere was interrupted by Rabbi Joseph Shubow, who confronted Hanfstaengl as he was talking to reporters in Harvard Yard. Rabbi Shubow demanded to know the meaning of a remark Hanfstaengl had made to the press on June 17, that “everything would soon be settled for the Jews in Germany.”

Trembling violently, Rabbi Shubow cried out, “My people want to know... does it mean extermination?”

A flustered Hanfstaengl replied that he did not care to discuss political matters, and the Harvard police quickly ushered the Nazi away to President Conant’s house for protection.

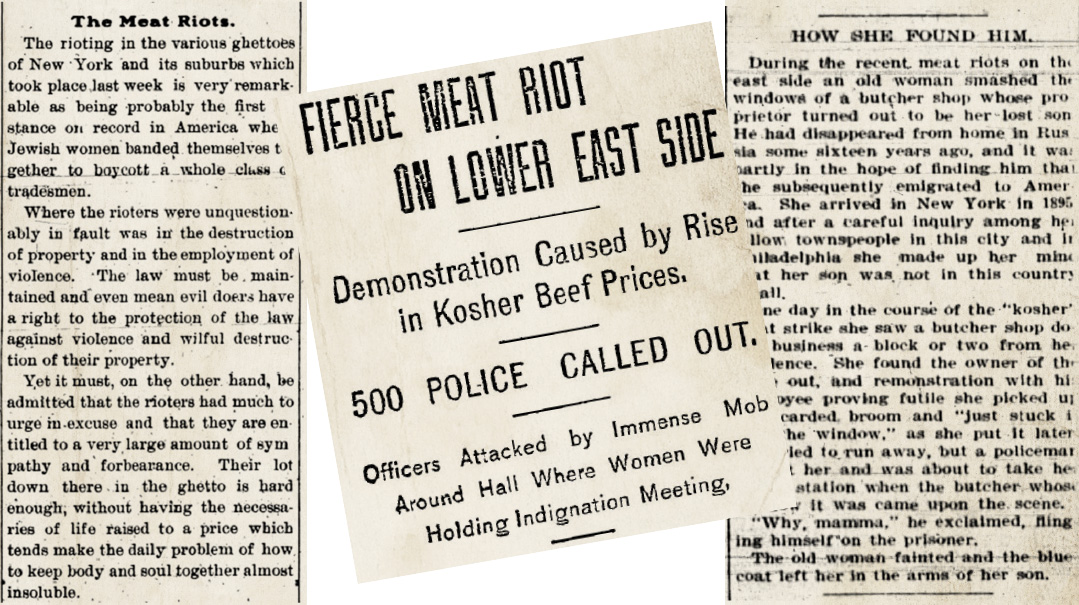

Support for the Nazi regime by Harvard University’s president, faculty, students, and newspapers during the 1930s wasn’t limited to the warm reception for Ernst Hanfstaengl. Conant’s predecessor as Harvard president, Lawrence Lowell, had introduced quotas to reduce Jewish enrollment. Lowell justified his anti-Semitism by declaring, “A strong race feeling on the part of the Jews was a significant cause of the rapidly growing anti-Semitic feeling in this country.” Conant had voted in favor of the anti-Jewish quota, but during his tenure as president, he utilized a more subtle formula to restrict Jewish enrollment.

Boycotting the Boycott

Shortly following the Nazis’ rise to power in 1933, Boston’s Jewish community organized a protest rally against anti-Semitic persecution in Germany. There was widespread support for a general boycott of German goods as well. Conant and Harvard University didn’t participate in either initiative, despite the fact that many prominent public figures in Boston signaled their support. In another telling incident, when Poland introduced segregated seating for Jewish students in its universities in 1937, a petition was signed by many American university presidents protesting this discriminatory practice. Harvard’s President Conant declined to sign.

Harvard Exonerates Hitler

A mock trial held by Harvard students and faculty in October 1934 acquitted Hitler of persecution of Germany’s Jews. Undergraduates presented arguments, and Harvard professors served as judges. The mock trial concluded, “The subject of Hitler’s persecution of Jews is ruled out as irrelevant.”

Conversely, the Harvard Crimson condemned a mock trial held in New York that found that Hitler’s persecution of German Jews amounted to “a crime against civilization.” Dismissing that mock trial’s findings because Hitler hadn’t been provided with an adequate defense, the Crimson also noted that the audience contained many Jews and was therefore prejudiced.

G.I. Rabbi Joe

In 1943, Rabbi Joseph Shubow voluntarily joined the US Army Chaplain Corps, where his empathetic and dedicated service earned him a Bronze Star. He was known to carry with him a portable aron kodesh, which he attached to his jeep. In March 1945, after moving with troops who had crossed the Rhine into Germany, Shubow conducted a Passover Seder in what had been Joseph Goebbels’s castle, a story that gained worldwide attention as front-page news. Following the war, he spent a year working in the DP camps, where he was instrumental in reuniting Jewish families and reviving the spirits of those who had suffered so much.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 991)

Oops! We could not locate your form.