Every Scroll a Story

| October 6, 2022The sifrei Torah stored in Israel’s National Library have been on a long journey of their own until they were brought safely to the Holy Land

Photos: Assaf Pinchuk and Hanan Cohen

It’s been two decadessince planning began to construct a new building for Israel’s National Library, and seven years since ground was broken. The building, located on Rechov Ruppin, the “Museum Row” of Jerusalem, is scheduled to open around Pesach time, and the colossal job of moving more than four million books and hundreds of thousands of manuscripts, maps, and memorabilia from the old building into the new has already begun.

Among the millions of items traveling to their new home are a number of sifrei Torah. For many of these seforim, this short trip (the old building is less than a kilometer from the new) will be the culmination of a journey that took place over thousands of years and across countless miles.

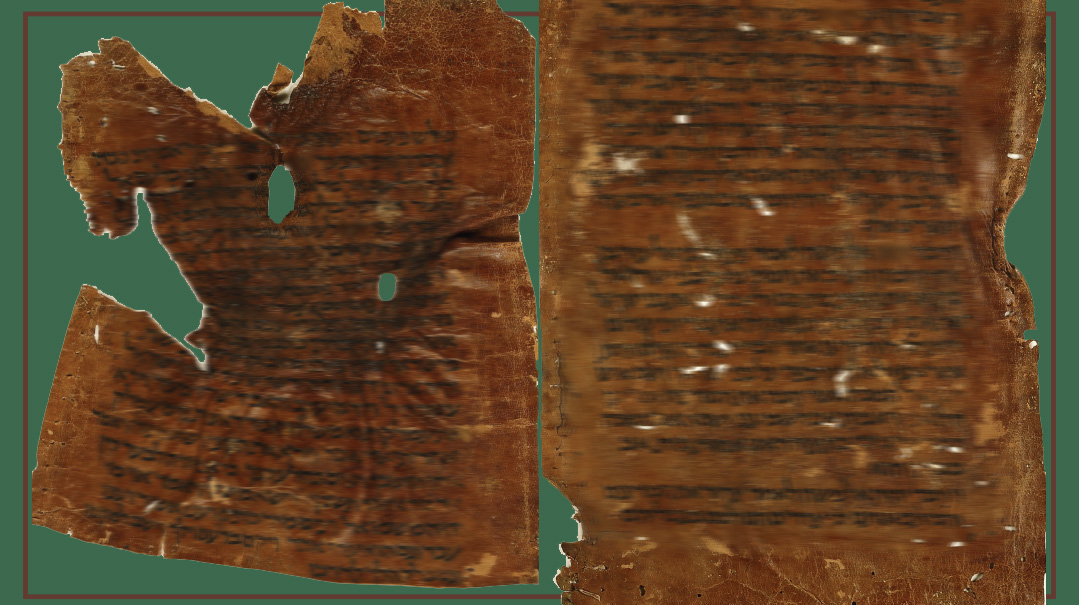

All that’s left of this ancient Yemenite sefer Torah are a few fragments, but it’s clear that the words haven’t changed

Words That Bind

No one is certain when Jews first came to Yemen. Some traditions date the community back as far as the reign of Shlomo Hamelech, who is said to have sent Jews to Yemen to buy gold and silver for the Beis Hamikdash. Others connect the ancient kehillah to the time of the first churban; there are those who say that Yirmiyahu Hanavi sent 75,000 Jews to Yemen right before that tragic destruction. Archaeologists have found written records from almost 2,000 years ago that mention the building of synagogues in Yemen.

When printing began, bookbinders would strengthen the spines of the books by sewing parchment fragments into the bindings. Housed in an airtight vault in the National Library are fragments of an ancient Yemenite sefer Torah. These fragments, about 1,000 years old, were sewn into the spines of books and thus preserved. Holes in the Yemenite Torah fragments clearly indicate the bookbinder’s stitching.

The history of Yemenite Jewry, like so many communities in galus, includes times of great prosperity, but also times of terrible persecution. Seeing pictures of these fragments — which, to help preserve them, are rarely taken out of their vault — one can’t help speculating about their backstory. How did fragments of a sefer Torah find their way into book bindings? Might it have happened during some terrible time of persecution, when the holy parchment was desecrated and sewn into spines of books?

Some scholars suggest a more optimistic scenario. When a sefer Torah became pasul, too old or damaged to use, the tradition was to bury it. But in a time and place where resources were scarce, another tradition arose. Bookbinders would take pieces of the sefer Torah (halachically permissible or otherwise) and use them to strengthen the bindings of other sifrei kodesh. When these seforim were damaged, they were placed in genizah — and the pieces of the Torah were discovered hundreds of years later.

And what about the original Yemenite sefer Torah itself, written 1,000 years ago? Had it originally been placed in an aron kodesh in one of the shuls mentioned in ancient texts? Was the sofer stam who wrote it a descendant of a Jew who helped decorate the Beis Hamikdash in gold and silver? Answers to these questions are lost in the mists of time.

What’s clear is that though these holy fragments come from a sefer Torah read long ago and far away, the words written on them are the same as the ones we read today. Yemenite parchment is a unique color, and some of the letters of their sifrei Torah look slightly different from those of other communities, but the words of a Yemenite sefer Torah — and of the remaining fragments of this most ancient treasure — are the same words that Jews all over the world and throughout time have read and cherished, have sometimes died for and always lived by.

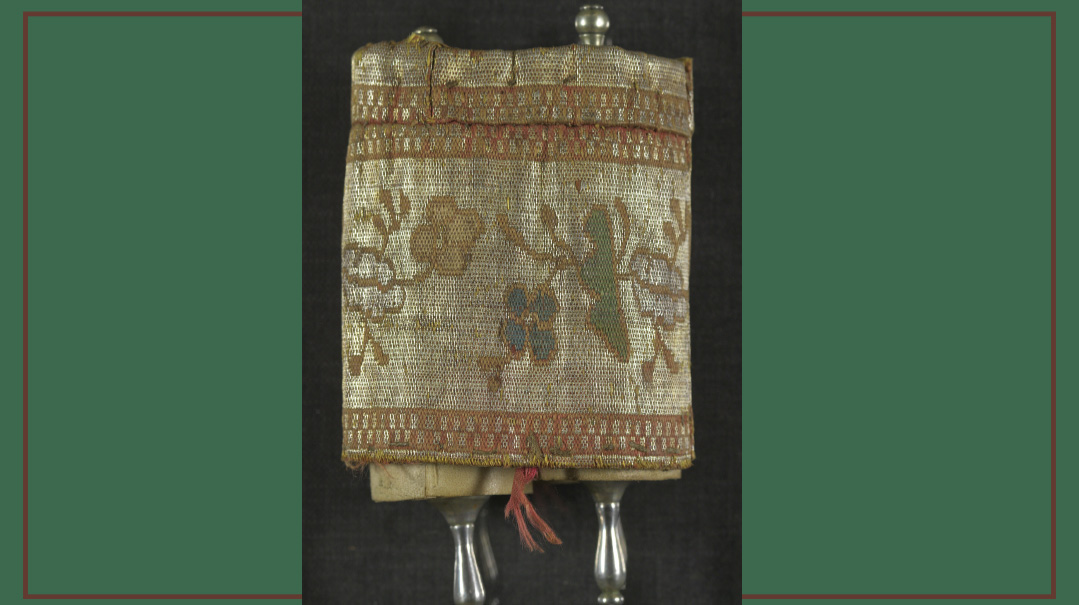

Whether Shaul Katzenellenbogen wrote this mini sefer Torah in memory of his short reign as a Polish monarch or kept it with him as per the law of kings, the 400-year-old scroll, just 10 centimeters tall, is a rare treasure

King for a Day

The National Library owns a tiny Torah that legend claims belonged to a king. King Shaul was the first king to rule Bnei Yisrael. His namesake, 16th-century Shaul Wahl Katzenellbogen was a king as well, but he never reigned in Israel, and his subjects weren’t Jews. Saul Wahl, as he’s better known, was king of Poland — for just one day.

The story of “le roi d’un jour,” the king for a day, falls somewhere in the gray area between historical fact and legend. Many different versions of the story exist, but most share certain basic elements. A Polish prince, Nicholas Radziwill, found himself in Padua, Italy, without the means to return to Poland.

Some versions of the story say he took a vow of poverty to expiate his sins and, now a beggar, he couldn’t return home. Others take the opposite view and say he came to Italy with a large contingent of servants and slaves and frittered all his money away. Still others claim robbers stole all the prince’s money and personal possessions.

In any case, all the versions concur that Prince Radziwill turned to the rav of Padua, Rabbi Shmuel Yehuda Katzenellenbogen, for help. Rav Katzenellenbogen generously gave the impoverished prince money to return home. In return, Rav Katzenellenbogen asked Radziwill to look up his son, Saul, a talmid chacham learning in Poland.

Prince Radziwill returned to Poland and kept his promise. In fact, he was so impressed by the young Saul Katzenellenbogen’s intelligence and honesty, he made him his personal secretary.

And that’s where, as they say, the plot thickens. King Stephen Bathory, ruler of Poland, died childless in 1586. Two branches of Polish royalty claimed the throne. According to Polish law, a new king had to be chosen immediately. The nobles decided to appoint a rex pro tempore, a temporary king, until they could agree on a new leader.

Prince Radziwill nominated a man known for his intelligence, honesty, and upright character… his secretary, the young Jew, Saul Katzenellenbogen. From then on Saul Katzenellenbogen would be known as Saul Wahl — “wahl” meaning “the chosen one” in German.

During his short reign, legend has it that King Saul issued a number of edicts to help protect his fellow Jews and abolish Polish anti-Semitic laws. And then, when a new Polish leader was chosen, the temporary Jewish king stepped down from the throne after a day (though some historians claim it was actually a few days or months) and returned to his previous role as an honest, upright Jewish talmid chacham and secretary to a Polish prince.

The legend or history of the king for a day can’t be proven, but there is one interesting piece of evidence housed in the National Library. An exquisite, tiny sefer Torah, estimated to be at least 400 years old, lies in its own miniature silver aron kodesh. The Torah itself is just ten centimeters tall. Its atzei chaim, the rollers used to roll the parchment, are made of wood and ivory — and on one of them you can clearly read the name Saul Wahl.

There’s a special mitzvah for a Jewish king to write a Torah and keep it with him. Did Saul Wahl Katzenellenbogen, prosperous assistant to a prince, already own a tiny sefer Torah before he became a king — and when he rose to the kingship, for however long or short a time, did he carry it with him? Did he write the Torah after he abdicated the throne, in memory of his short reign as Polish monarch? Or are those historians who say his reign was a matter of months correct, and did he actually have the tiny Torah scroll written during that time?

All unanswerable questions. But no matter which version of the story is true, whatever are the facts behind the tiny sefer Torah, a few certainties emerge from the story: Saul’s father, the rav in Italy, exhibited true Jewish chesed when he helped a penniless non-Jew return home. And Saul himself must have had an impeccable reputation for the Polish noblemen to trust him as temporary monarch, knowing he wouldn’t let power go to his head and fight to remain on the throne.

You can’t just walk into the National Library and see the Wahl Torah; like the Yemenite fragments, it’s generally kept in storage to preserve it in all its beauty for all time. But the story of the king for a day and his sefer Torah, and of the chesed and honesty that are the story behind the story, preserves a message that is available to anyone, inside or outside the sealed vaults of the National Library.

The Long Road from Rhodes

Rhodes is a small island in southern Greece, not far from Turkey. The kehillah there was established 2,000 years ago: It’s mentioned in the ancient Sefer Hamaccabim and by Flavius Josephus. The famous 12th-century traveler, Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, described a community of 400 or 500 Jews. By the 20th century, close to 2,000 Jews lived in Rhodes, in a prosperous community with four shuls.

The Nazi conquest of Greece spelled the end of this community. You may never have met a survivor or descendant of Holocaust survivors originally from Greece; sadly, that’s because so few survived. Almost 90 percent of Greece’s Jews were murdered, one of the highest percentages in all of Europe. The community wasn’t that large to begin with, fewer than 80,000, and only a handful of Greek Jews survived.

The destruction of the Rhodes community in July 1944 was especially heartbreaking; just three months later, the Germans retreated from Greece under intense pressure from the Allied armies. The Rhodes Jewish community suffered the last Greek deportation, one final act of cruelty by the Nazis. They were crammed into boats in the blazing heat of the Mediterranean summer, without food or water, and transported to the Greek mainland. Many died on the voyage; those who survived were murdered in Auschwitz.

But while tragically few Greek Jews survived to share their harrowing history, there is one “survivor” whose extraordinary story lives on — a sefer Torah stored in the vaults of the National Library.

The story of the Rhodes Torah begins far away from the small Greek island. Scholars who study ancient parchments and different types of Hebrew lettering believe it was written in Spain, before the expulsion in 1492. (The name Yaakov ben Abraham Mar Hayyim, a prominent Spanish Jewish family, appears on the eitz chaim used to roll the sefer Torah.) It was probably carried to Rhodes by Jews expelled from Spain, who refused to convert to Christianity. The distance between Spain and Greece is almost 1,500 miles, an epic journey in those days.

Some of the Spanish exiles ended up in Rhodes; in fact, many residents spoke Ladino, the Judeo-Spanish language that spread throughout Europe after the expulsion. The Rhodes sefer Torah ended up in the Kahal Shalom Synagogue, established in 1557, the oldest shul in Greece. Amazingly, the shul building survived the devastation of the Shoah, and still is in occasional use today.

On that terrible day in July 1944 when the Jews were rounded up and sent to their deaths, their Greek neighbors began looting their homes and institutions. But a small number of Jews with Turkish citizenship were spared from deportation, and one of the Turkish Jews who remained tried to find a safe place for the precious, ancient Torah.

Sheikh Suleyman Kasiloglou was the mufti of Rhodes, the Muslim religious leader and judge. He had good relations with his Jewish neighbors and offered to hide their treasures. The mufti found a place for the Torah where the Nazis were unlikely to search: under the pulpit in a local mosque.

The last parshah read in the shul before the Rhodes community was destroyed and the sefer Torah was hidden was parshas Pinchas. That parshah begins with Hashem giving Pinchas a “bris shalom.” Almost a year later, the Rhodes Torah, taken from a shul called Kahal Shalom, was returned by the mufti “b’shalom” to the Jewish Brigade, Jewish soldiers from Palestine fighting for the British Army. They returned it to the last remnants of the kehillah.

In 1999, the sefer Torah that had wandered through Europe, had survived a terrible exile and a devastating war, and had spent almost a year hidden in a Greek mosque finally found its way home to Yerushalayim. The Rhodes community sent two sisters, Jacqueline Benatar and Miriam Pimienta Benatar, to deliver the Torah to the National Library. The Benatars gave the Torah to the library as a memorial to all the martyred Jews of Rhodes murdered in the war — including their own parents.

As the Jews in Greece were being rounded up for deportation to Auschwitz, how would the ancient Torah, brought to the island of Rhodes by exiles from Spain hundreds of years before, survive the onslaught?

Final Destination

One and a half million Jews joined the Allied armies in their fight against Germany. More than 150,000 were killed in action and many more were wounded or taken prisoner. Thousands received citations for bravery from the various Allied armies.

These brave young Jews included 30,000 soldiers from Eretz Yisrael, a large percentage of the small Yishuv, who joined the British Army to fight the murderous Nazis. These Jewish “Palestinians” helped free Italy and Greece — and some of them were among those who liberated Rhodes.

Daniel Lipson, reference librarian at the National Library, searches the library for works rescued from the fires of the Holocaust. (See Issue 907 for more about Lipson’s work on the Otzar HaGolah collection). In his research, he found two fascinating short articles about Rhodes, published soon after VE Day in the Palestine Post (today the Jerusalem Post).

On June 20, 1945, the Post wrote about a Jewish soldiers’ club opening in Rhodes — the first Jewish institution organized since the Jewish community had been wiped out a year before. Several soldiers originally from Haifa had begun to systematically search the island for any surviving Jewish books or artifacts. (The article also mentions a Sergeant Samuel Negrin of Jerusalem as one of the “Palestinian” soldiers. Negrin was awarded a medal by the British Army for parachuting behind enemy lines and participating in the liberation of Tripoli).

Apparently these young Jewish soldiers succeeded in their mission: An article dated September 23, 1945, describes how 80 cases of books from a Jewish library had been found and were sent to Hebrew University’s library on Mount Scopus (Har Hatzofim), the predecessor of the National Library. According to the article, most of the books were sifrei kodesh, and some went as far back as the 16th century.

As with many survivors, the war’s end didn’t bring an end to the books’ wanderings. In 1948, Har Hatzofim became no-man’s-land, and the university and library were virtually abandoned. Jewish convoys were allowed to visit every few weeks, and soldiers would sneak out some books with every visit, but for several years much of the library’s collections lay unused, gathering dust on shelves.

For 19 long years, the IDF, Jordan, and the United Nations were all involved in negotiations over access to the books. Only after the Six Day War, when Yerushalayim was reunited, did all the books — including the Rhodes seforim — become available once again.

These last remnants of Rhodes Jewry survived the Shoah and nearly two decades of exile, and finally, in 1967, these sifrei kodesh; meforshim on Tanach and Talmud, halachic responsa, books of rabbinic sermons — the Torah wisdom of centuries — returned to the library, to be read and studied by our people.

The world’s smallest sefer Torah, just over two inches tall, is stored in a vault and rarely seen, but its partner, another tiny Torah from an 18th century maggid, is used in the National Library’s Minchah minyan when the Torah is read on fast days

The Living Torah

The Yemenite fragments. The Polish sefer Torah of the “king for a day.” The Rhodes Torah, saved from the inferno of the Holocaust. All these precious items, part of Jewish history and our great legacy, are stored for safekeeping and preservation in Israel’s National Library. Their stories can inspire us, but once they take their final journey to the new building, they’ll be taken out of the vault only rarely for study by scholars.

But our Torah is a Toras Chaim, a living Torah, and the library includes sifrei Torah that are used, as well. Rabbi Nachum Zitter, head of reference in the National Library, also serves as unofficial gabbai there. (Full disclosure: he’s also my son). Among other jobs, he organizes a daily Minchah and Maariv minyan. On fast days, when Minchah includes Krias HaTorah, the baal korei reads the Torah reading… using the library’s 200-year-old sefer Torah.

The scroll is kept permanently turned to parshas Ki Sisa, the leining for Minchah on a fast day, as rolling it in either direction might harm the aging parchment or the letters. It might not be the library’s oldest or its smallest Torah, (that distinction goes to a tiny Torah — just 2 ⅓ inches tall — also stored in the library vaults and rarely seen) but Rabbi Zitter says that when it’s held up for hagba’ah, since it’s so light, you’re looking at 20 columns of beautiful Torah script, a sight to see.

This small Torah, in use for decades at the library, has a story too. Binyamin Richler, now retired, was head of the Institute of Microfilmed Hebrew Manuscripts Section of the Library for many years, and regularly joined the Minchah minyan. Some years ago, Richler’s father visited him from Canada and asked him to research if there were any manuscripts written by their ancestor, Rav Yehuda Leib Edel, a maggid and talmid chacham who lived in the mid-18th to early 19th century. Reliable sources record that Rav Edel met the Vilna Gaon and that Rav Chaim Brisker kept his sefer, Mayim Tehorim, a work about Seder Taharos, on his desk.

Richler began searching databases from around the world, looking for manuscripts and seforim written by Rav Edel, and he found one. At the National Library. It had been donated soon after the Six Day War.

Yes, the small Torah that Richler had heard leined regularly in the library on fast days belonged to his great-great-great-great grandfather!

It’s unclear whether Rav Edel actually wrote the sefer Torah, though family lore says he did. In any case, it makes sense that an itinerant maggid, who traveled from town to town sharing his wisdom and drashos, would carry a small Torah with him.

A Torah that would remain in use hundreds of years later and is about to find a permanent home.

New Home, New Torah

As of today, there is no Shacharis minyan at the library. That will change in the near future, when the new building opens, with a shul that will be open to library staff, visitors to the museums across the street, and government workers in nearby office buildings.

And it will have a brand-new sefer Torah.

This new Torah was commissioned specifically for the new building. Rabbi Zitter organized a hachnassas sefer Torah recently, with donors, patrons, librarians, and library staff given the honor of finishing the final letters.

And while this scroll is brand new, the words inscribed on it are identical to the words inscribed on the sifrei Torah stored in the vault. Our people’s Torah has been with us through the desert, stayed with us through our original settlement of our land, wandered with us through exile after exile… and accompanied as we’ve returned to Eretz Yisrael. Each sefer Torah tells its own story — and together, they tell the story of a people bound to every word, every letter, every space of every sefer Torah.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 931)

Oops! We could not locate your form.