Don’t Talk, Just Daven

| August 1, 2023As I did not understand a word except now and then an Amen or Hallelujah, my attention was directed to the haste with which they covered their heads with their hats as soon as the prayers began

Title: Don’t Talk, Just Daven

Location: Philadelphia

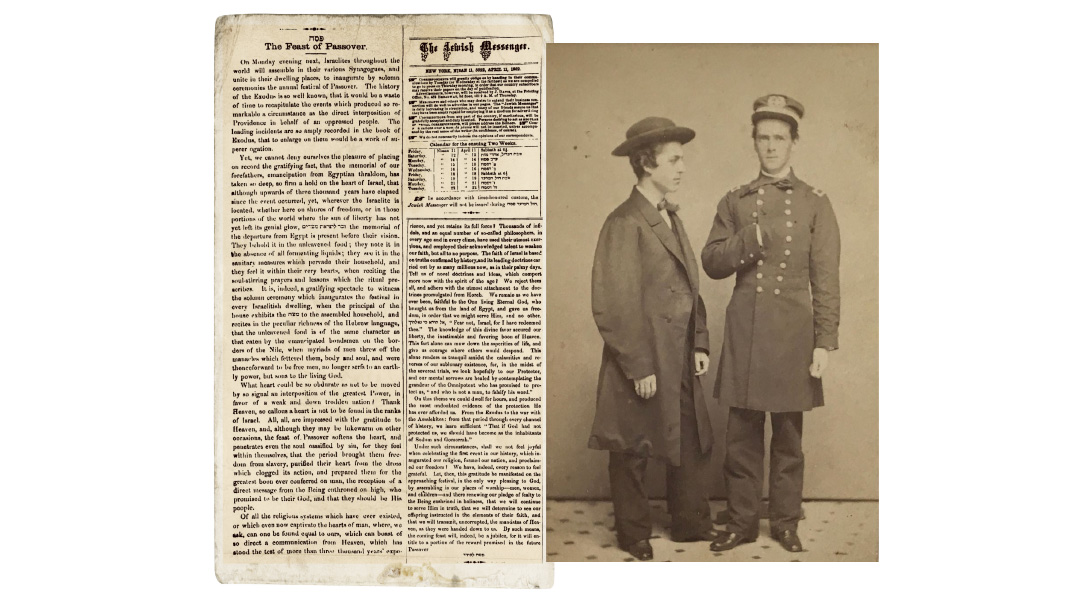

Document: Mock-up of Letter from Dr. Benjamin Rush

Time: 1787

Dr. Benjamin Rush (1745–1813), one of America’s Founding Fathers, distinguished himself as a Philadelphia physician, medical educator, and pioneer in psychiatry. His prominence extended beyond the field of medicine; he was an enthusiastic patriot and politician, holding the position of surgeon general at the military hospital for the Middle Department of the Continental Army, as well as being a signer of the Declaration of Independence. As a delegate to the Continental Congress, he played a crucial role in Pennsylvania’s ratification of the Constitution in 1788.

Dr. Rush championed such causes as abolition of slavery, women’s education, prison reform, and free public education. Dr. Rush’s work for these causes brought him into diverse social circles, including that of Jewish Philadelphia, where he met Jonas Phillips.

Patriarch of one of America’s most prominent Jewish families of the 18th and 19th centuries, Jonas Phillips (1736–1803) grew up in Frankfurt and moved to the colonies in 1756. As a successful merchant and patriot in New York City, he left for Philadelphia when the British took over New York. While residing in Philadelphia, he was one of the founders of Congregation Mikvah Israel.

His wife Rebecca (1746–1831) was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, to Rev. David Mendez and María (Tziporah) Machado, who had both been born in Portugal to longstanding Marrano families. Rebecca’s parents settled in New York, where David Mendez Machado served as minister of Congregation Shearith Israel, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue.

At the age of 16, Rebecca Machado married Jonas Phillips. Their union would be blessed with 21 children and countless grandchildren, most famously America’s first Jewish naval commodore, Uriah Phillips Levy, and the colorful writer and politician Mordecai Manuel Noah.

One of the Phillips daughters was the subject of a historic letter written by Dr. Rush that provides the first known description of a Jewish wedding on American soil. Rich with detail, it’s a vivid, firsthand glimpse into an 18th-century Jewish ceremony.

The non-Jewish Dr. Rush eagerly accepted an invitation to attend the wedding of Rachel Phillips to Michael Levy of Virginia on June 27, 1787. Dr. Rush provides us with a description of what seems to be a minyan for Minchah prior to the start of the proceedings:

At 1 o’clock the company, consisting of 30 or 40 men, assembled in Mr. Phillips’s common parlor, which was accommodated with benches for the purpose. The ceremony began with prayers in the Hebrew language, which was chanted by an old rabbi and in which he was followed by the whole company. As I did not understand a word except now and then an Amen or Hallelujah, my attention was directed to the haste with which they covered their heads with their hats as soon as the prayers began, and to the freedom with which some of them conversed with each other during the whole time of this part of their worship.

The author then goes on to describes the wedding ceremony in great detail:

As soon as these prayers were ended, which took up about 20 minutes, a small piece of parchment was produced, written in Hebrew, which contained a deed of settlement and which the groom subscribed in the presence of four witnesses. In this deed he conveyed a part of his fortune to his bride, by which she was provided for after his death in case she survived him.

The ceremony was followed by the erection of a beautiful canopy composed of white and red silk in the middle of the floor. As soon as this canopy was fixed, the bride, accompanied with her mother, sister, and a long train of female relations, came downstairs. Her face was covered with a veil which reached halfway down her body.…

Another prayer followed this act, after which [the rabbi] took a ring and directed the groom to place it upon the finger of his bride. The groom, after sipping the wine, took the glass in his hand and threw it upon a large pewter dish which was suddenly placed at his feet. Upon its breaking into a number of small pieces, there was a general shout of joy and a declaration that the ceremony was over. The groom now saluted his bride, and congratulations became general through the room.

I asked the meaning of the canopy and of the drinking of the wine and breaking of the glass. I was told that in Europe, they generally marry in the open air, and that the canopy was introduced to defend the bride and groom from the action of the sun and from rain. Their mutually partaking of the same glass of wine was intended to denote the mutuality of their goods, and the breaking of the glass at the conclusion of the business was designed to teach them the brittleness and uncertainty of human life and the certainty of death, and thereby to temper and moderate their present joys.

A YIDDISHE MAMA

Dr. Rush later shared an occurrence from later on during the celebration: “I stayed, however, to eat some wedding cake and to drink a glass of wine with the guests. Upon going into one of the rooms upstairs to ask how Mrs. (Rebecca) Philips did, who had fainted downstairs under the pressure of the heat (for she was weak from a previous indisposition), I discovered the bride and groom supping a bowl of broth together. Mrs. Phillips apologized for them by telling me they had eaten nothing (agreeably to the custom prescribed by their religion) since the night before. Upon my taking leave of the company, Mrs. Phillips put a large piece of cake into my pocket for you, which she begged I would present to you with her best compliments. She says you are an old New York acquaintance of hers.”

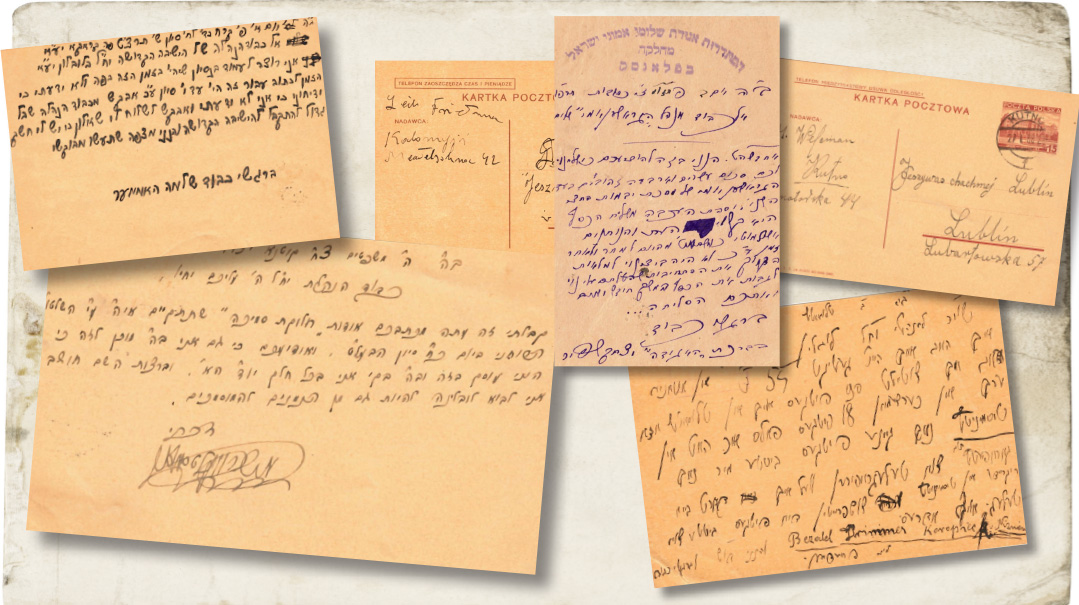

CODED IN THE MAMMA LOSHEN

Jonas Phillips earned his stripes in America as a soldier during the Revolutionary War. Famously, Phillips employed his knowledge of Yiddish to draft a letter to a relative and business correspondent in the Netherlands, also providing information about the conflict with Great Britain, along with a copy of the Declaration of Independence. As the British authorities didn’t recognize the language, they mistakenly assumed the letter was written in code and disposed of it.

Thank you to Rabbi Dr. Meir Soloveichik of Congregation Shearith Israel, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue for making us aware of this fascinating letter.

The text of this letter was published in The Letters of Benjamin Rush, edited by L. H. Butterfield (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1951), vol. I.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 972)

Oops! We could not locate your form.