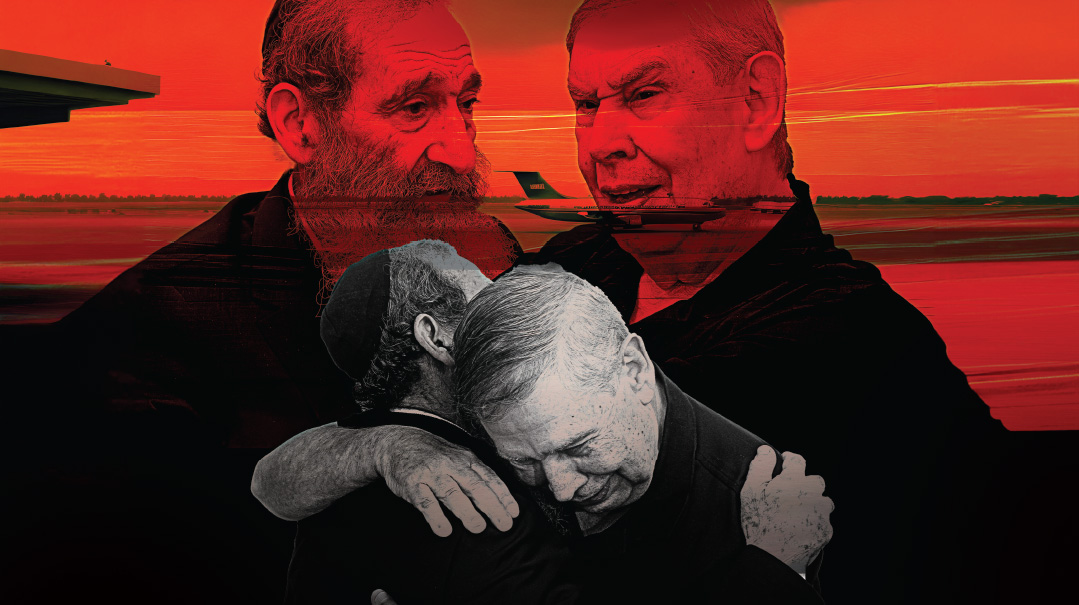

A Uniter at the Helm

Eric Goldstein’s selection as head of the largest Jewish philanthropy in the world surprised some, but early returns indicate he’s the man for the job

Eric Goldstein started his life as a Wall Street lawyer, but found himself more moved by helping people than personal gain. His surprise selection as the head of the largest Jewish philanthropy in the world surprised a few, but early returns indicate he’s the man for the job. For the chareidi community, he might just be the leader who ushers Flatbush and Boro Park through Federation’s doors

I

n a Manhattan brownstone just east of Riverside Park, there is a charming little shtiebel where my father is rav, the kind of place with an old-fashioned kiddush and banter as well-worn as the tiles. When the skilled baal korei, an accountant named Pinky, is away for Shabbos, he makes it his responsibility to find a substitute. Pinky tells me about a local teenager he calls upon.

“He’s a great kid, always happy to help — and he can really lein!”

When Adin Goldstein reads from the Torah, his parents come to the shtiebel too, his mother listening proudly from behind the heavy drapes that separate the ezras nashim from the main shul. And his father?

“If you want to know who Ricky Goldstein is,” a shtiebel old-timer tells me as he sprays kichel crumbs on the thick table cloth and knocks back small cups of Chivas, “forget his fancy job and speeches. Come watch him, see his face, when his son is leining; then you’ll ‘get’ him.”

NOT JUST PERSONAL AMBITION

In the shtiebel they see a proud father, but the wider Jewish world knows Eric Goldstein as the CEO of UJA-Federation of New York. It’s a position that calls for fund-raising abilities, diplomatic finesse, genuine heart, and an ability to deal with every kind of Jew on the planet.

Our interview is scheduled for eleven o’clock am. At precisely 11:02 the door to his office opens and he welcomes me.

The first thing that strikes you about Ricky Goldstein is his boyishness, more of the cool high-school gym teacher, less prominent bureaucrat.

He wasn’t supposed to be doing any of those things.

His father is a lawyer, his mother a judge.

“The only question was what type of law. I remember how my brother had lousy handwriting as a child, and my mother asked, ‘How are they going to read your answers on the bar exam if you don’t write nicely?’ ”

The current leader of UJA-Federation of New York — the most generous and active local Jewish charity in the world, with an annual budget of over $200 million — remembers being a bit of an activist while in school, the Yeshiva of Central Queens. “But in terms of worldview, sensing the needs of the wider Jewish community beyond my little world, I have to credit Rabbi Louis Bernstein, at Young Israel of Windsor Park. Our rabbi wasn’t flashy, he preferred substance to style, but he made a very big impact on us.” Rabbi Bernstein, a three-term president of the Rabbinical Council of America, was known for reaching across Jewish lines while remaining true to Orthodox principles.

Like so many others who went on to leadership roles in the Jewish community, Goldstein recalls the events of 1967 as formative. “This tiny country captured our imagination, our hearts and minds. I became much more aware of how connected we are to each other.”

Eric followed the script, graduating yeshivah and entering Columbia College, then Cornell Law School.

The plan was that he would join his parents’ law firm, Goldstein and Goldstein, but high marks and a successful internship saw an offer come his way from the prestigious law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison.

He worked on Wall Street, and as a young single living on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, he found a calling. “It’s a neighborhood filled with older people, often living on their own. I heard about a UJA-supported agency called Dorot which addresses the needs of seniors, food and company. I got involved with Dorot and had my first taste of real community involvement: We didn’t only bring the warm meals to the elderly, but we went shopping and connected with them. We created a curriculum, books to read with them and discuss. I found that I enjoyed not just the mitzvah, but the administrative end as well, helping to make it happen.”

Along with the chesed and kindness, a bond was developing between a young, single, Jewish lawyer and the historic organization.

The Federation has been around for a long time. First created in 1917 as the Federation for the Support of Jewish Philanthropic Societies of New York City, it eventually merged with the United Jewish Appeal. In 1986, the umbrella organization of UJA-Federation of New York was formed.

The connection between the young lawyer and UJA-Federation would only deepen.

THE POWER OF COMMUNITY

When Eric married Tamar Koschitzky of Toronto, he joined a family known for philanthropy and communal involvement. As they started their own family, Eric found a new frontier for his activism.

Education.

“When we started to send children to school, I was exposed to a new reality, that of Orthodox day-school tuition. As my children got older, I got involved with Manhattan Day School/Yeshiva Ohr Torah, later Ramaz, and realized just how serious the issue is.”

The CEO of UJA-Federation is seated at a round conference table in the corner of his spacious office, but it’s evident that he hasn’t forgotten the stress placed upon a young father of several children.

“I started to look at the financials, not just of MDS, but of other Orthodox schools as well. Eighty percent of the budget goes to paying teachers, so that’s not a place to cut. The teachers are already underpaid. It became clear to me that we had to find new sources of funding, harness the power of the wider community.”

So as Eric Goldstein rose through the ranks at work, eventually becoming partner at Paul, Weiss, he also found time to join the MDS board of directors, ultimately becoming the school’s president.

“The schedule was tough, a lawyer works long hours, but the way I see it, you’re investing most of your money, time, and energy in your children: shouldn’t their school be a priority for you? My wife also comes from that type of home, and she also encouraged me to find time for it.”

Goldstein is eager to dispel any negative notion about his former profession and credits his law firm with supporting his increasing communal activity. “Everyone at the firm had their causes, organizations to which they donated time.”

But he remembers one particular attorney who did more than that.

A BIG IMPACT

“There was an Orthodox lawyer there, a yeshivah graduate, and we used to speak all the time and we sometimes learned mishnayos during lunch. One day, the news spread that he was leaving, and he wrote a memo to all the partners explaining his decision. Even though he had a growing family, he felt a responsibility to his community, and would be joining a national Jewish organization.”

“That made a big impact of me; it was a real kidush Hashem.”

Did Rabbi Chaim Dovid Zwiebel’s decision to leave Paul, Weiss for the Agudah influence Eric Goldstein’s eventual move to public life?

“Maybe. I can tell you that we still speak from time to time and I always hang up the phone enriched from our contact.”

Last year, the two leaders stood by side in lower Manhattan, leading a press conference along with the Orthodox Union’s Alan Fagin — also a former New York City lawyer — campaigning for school choice.

THE SEARCH

Active as Goldstein was outside the office, it was the programs connected with UJA that claimed his heart. Along with serving as a board member at Ramaz and president of the Beth Din of America, he took an active role in overseeing UJA’s work in Eretz Yisrael and in the former Soviet Union. He would eventually become a member of the executive committee, chair of its Lawyers Division and Global Strategy Task Force and, ultimately, vice chair of UJA’s board.

So when the news came that John Ruskay, longtime CEO of UJA-Federation was retiring, Eric was a natural to join the search committee. Federation insiders understood the challenge.

Candidates — among them the finest and most accomplished activists — came through the revolving doors at the UJA offices, looking for the job at what is by far the largest Federation in North America. With the opportunity to serve as a bridge between more than 50,000 donors and beneficiaries in more than 70 countries, it was literally a chance to change the world. One day, John Ruskay turned to Eric Goldstein. “Eric,” he said, “you’re into it, you get the job, and you seem to enjoy this sort of thing. Maybe you should do it?”

Ruskay recalls the moment. “I wasn’t involved in the search, he was on the search committee and I wasn’t, but he’d spent his adult life within UJA. It felt right.”

Goldstein also remembers the conversation. “Believe it or not, it was a complete surprise: I hadn’t been thinking in those terms. I can’t tell you I’d never dreamt of devoting myself full-time to public life, but just not yet.”

He shrugs. “There’s never a perfect time, right? You have to make it the right time, I guess. I spoke to my wife and kids, some close friends, and everyone was very encouraging.”

In January of 2014, the announcement was made. Eric Goldstein was the new CEO of UJA-Federation of New York.

TWO SURPRISES

The wider Jewish community took notice of the hire. The Forward analyzed the pick by pointing out two facts: Goldstein… offers two surprises: Goldstein is Orthodox, and he does not come from within the Jewish professional world.

Regarding the second item, the “outsider” label, the move appears to have been the start of a trend. In the years since, several other major organizations followed the route, reaching into the private sector for leadership (including the country itself, which eschewed the political insiders in favor of a businessman).

“Just because it works, that doesn’t mean it’s always right,” the CEO is quick to point out. “You have these super-talented people who make a decision to give their lives over to public activity. They spend years in the trenches, often underpaid and underappreciated, and then, when there’s a chance for promotion, the board of directors reaches outside. You also have to be able to promote from within. There’s no rule: different situations call for different things.”

Regarding the Orthodox thing?

“I’m the first Orthodox Jew to occupy this position at UJA Federation.”

And it’s significance? He measures his words carefully. “Jewish unity is critically important. And I’m not saying we will resolve halachic challenges or significant differences, but my background helps to appreciate perspectives and to build bridges and understanding across communities.”

TO HELP IT GROW

Before meeting Goldstein, I’d heard it was his intervention that ushered in a shift in a longstanding Federation tradition: Rather than being antagonistic toward tuition tax credits and various other forms of governmental assistance to yeshivos and other non-public schools, the Federation actually established a “Day School” desk.

I catch the first sign of impatience in the mild-mannered CEO. “ It’s just not true. The Federation was keenly focused on supporting Jewish education long before I became CEO, and, for many years advocated for increased government assistance to non-public schools within church and state laws. Our position is that the public schools are receiving $19,000 per child, and we’re just asking that private schools receive a fraction of that. If yeshivah children were in public school, the government burden would be that much bigger. It might be a personal cause, since I’m a day-school parent, but it’s certainly not my mission. It predates me.”

That said, yeshivos and Bais Yaakovs do have special appeal to the CEO.

“For many years, UJA has been supporting things like supplemental health, pension, and life-insurance benefits for rebbeim in Torah Vodaas and Chaim Berlin, all sorts of projects that many in the community aren’t even aware of. We’re big believers in the success of all the community’s yeshivos and are happy to do our part.”

Rabbi Zvi Bloom of Torah Umesorah echoes that. “Working with Eric has been a pleasure because he has the genuine appreciation for Torah education: He’s tasted the beauty of the system and wants to see it thrive.”

Avrohom Biderman, who’s worked with Goldstein on several communal issues, sees the CEO’s commitment to Torah education as a mark of good judgment. “It isn’t just that he himself is Orthodox, which is nice; it’s also that he’s a sharp enough observer of demographic trends to appreciate the community and its rise. He isn’t scared of it — the opposite, he wants to help it flourish.”

Specifically because he’s an insider, Goldstein has hopes for the Orthodox community.

UJA, he makes it clear, sees no distinctions between Jews. “Where there is need, we and our network agencies work to offer a meaningful response. We serve many in the chareidi community — for example through Met Council, local Jewish community councils, the Boro Park JCC, the Hebrew Free Loan Society, the Fund for Jewish Education and grants to Torah Umesorah and many yeshivos.”

But he’d like it to be a two-way street. “I want people across the Jewish community to have a seat at the table. I’d love to see chareidim more engaged with us. You can’t criticize our allocations when you’re not part of the process.”

He corrects himself. “You can criticize it if you’d like, but it’s hard to take it seriously if you’re not here.”

He points at me. “Your grandfather, Rabbi Chaskel Besser, is an example. He was an Agudah leader, and he wore a shtreimel. But he was able to influence Ronald Lauder, who’s not Orthodox, to fund so many important causes, because he took them seriously. He learned how to connect with people who didn’t think exactly like him.”

He pauses. “My in-laws once visited him one Motzaei Shabbos, and he took them to hear the symphony. Rabbi Besser spoke about classical music with such passion and feeling. It didn’t diminish his faith one drop and only made him more effective. The charedi community needs more people like that if they want to have a hope of attracting Ronald Lauders to their causes.”

He shares a contemporary example.

Immediately after Hurricane Sandy struck, the Federation used emergency funds to help many chareidi institutions, including Yeshiva Darchei Torah of Far Rockaway, with rebuilding.

“We allocated well over a million dollars, including funds for tuition relief, to a number of yeshivos and shuls affected by the storm. Rabbi Bender at Yeshiva Darchei Torah sent a letter to his entire parent body asking them to express hakaras hatov to the Federation. We received over 600 small donations. Over 600! From my point of view, they were an indication that we’d engaged 600 more Jewish homes.”

“I attended Darchei’s dinner last year, as a sign of esteem for them and acknowledgement of that connection. You don’t have to give a lot of money to the Federation to have a voice, but don’t stay outside either!”

“You know,” he half-smiles, but he clearly isn’t joking, “I would welcome an invitation to any chareidi shul to discuss working together. I get it, the chareidi community doesn’t support everything that we support, but we are there to support the entire community and that shouldn’t close the door between us. Let’s get together and actively work to address common challenges across New York. Chesed is chesed. A hungry Jew is a hungry Jew. We should find a way to jointly identify needs, share best practices, and work together side by side.”

A LEARNING EXPERIENCE

Under Goldstein’s direction, the Federation is flourishing. As the organization launches its centennial-year celebrations, fund-raising is up. Programs are thriving.

“We try not to provide money alone, but also to empower people to help themselves, to create change. For example, we created food-choice pantries, rather than standard food pantries: cookies ‘cost’ more points than vegetables, so we’re encouraging consumers to make smart choices. That’s our approach to any project we undertake, not just to give and keep the cycle going, but to try to help people get out of poverty as much as possible.”

There have been challenges. FEGS (Federation Employment Guidance Services), an 80-year-old not-for-profit in the UJA network which helped the disabled and unemployed with benefits and other services, shocked the wider Jewish philanthropy world when it suddenly filed for bankruptcy not long after Goldstein took the Federation helm.

“It wasn’t the easiest time for Eric, he was new, but that’s when we saw the litigator in him,” says a Federation insider. “The donors were upset, but we ended up being able to transfer all UJA-supported FEGS programs to other agencies in our network without any disruption of service to clients.”

John Ruskay, now executive vice-president emeritus of UJA-Federation, laughs knowingly when I ask him why this emeritus relationship seems to work when so often in organizational life, there is friction. “Yes, I get asked that question often. I think the reason is twofold. One, I was really ready to leave, so I had no problem stepping back. Second, both Eric and I care deeply for the organization, so our relationship is based on that shared respect for the work it does.”

Malcolm Hoenlein, the executive vice chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, sees another ingredient in Eric Goldstein’s success. “He’s so easy to work with because he’s low-key. He isn’t looking for credit. He wanted this job for the right reasons, to get things done, which is why he’s succeeded where others haven’t, why he’s able to work with all sorts of people.”

A GIFT

The CEO tries to get out of the office and spend time on the ground. He often visits schools, generally those that are taking advantage of the UJA-Federation Day School Challenge by increasing their endowment funds and earning matching funds from UJA-Federation.

The Federation’s budget comes entirely from donations, and Eric spends a significant amount of time engaging donors. He is heavily involved in community issues and allocating the grants, but his favorite part of the job is meeting the beneficiaries of the programs.

“Spending time with the people we help and seeing the impact of programs we fund is very rewarding.”

The hardest part of the job, according to the CEO, isn’t fund-raising. “When I signed up for this, I didn’t realize how much time I’d be investing in getting involved in disagreements, trying to find common ground between people and groups. The politics in organizational life is rough.”

Does he ever dream of turning back, of walking down the long hallway and rolling up his sleeves at Paul, Weiss again?

His eyes fly open and he looks like he’s twenty-five years old. “I miss my old partners, but I love this job.”

He leads me to the large desk, covered in booklets and brochures detailing current and future projects and he picks one up.

“This is the greatest job in the world. Every day is a gift.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 642)

Oops! We could not locate your form.