Spot It

What was behind my son’s attacks of agonizing pain?

As told to Faigy Peritzman

Four to six weeks. Four to six weeks. The words beat a steady rhythm in my head against the background of my son’s shrieks of pain. We cannot deal with this for another four to six weeks, I fretted. I cannot deal with this for another minute!

But Moishe kept screaming, writhing in agony, and there was nothing we could do to soothe or comfort him. I couldn’t believe that the doctors had nothing to offer, and that they predicted this level of excruciating pain would last for four to six weeks, while we just looked on helplessly. How would such a young child deal with that?

It had all started sometime after Succos.

After a month of Yamim Tovim, I was eager to get my family of three young kids back on schedule. I run my own business from home, plus I was expecting, so having everyone underfoot while keeping to my deadlines had been no easy feat.

I hoped things would now get back to normal.

Except that a few days after Succos we all came down with Covid.

Okaaay. Getting back to routine would take a bit longer.

We made it through the virus relatively easily, and I breathed a sigh of relief when we finished quarantine. But then my two girls got some sort of other virus, unrelated to Covid, and I was back to playing full-time nurse — again. When they finally went back to school/playgroup, six-year-old Moishe, my oldest, came down with strep. This was getting a bit out of hand, but what could I do? Finally, after a few days of antibiotics, I sent him off to school, cautiously anticipating a normal week.

That night, Moishe woke me up. “My stomach hurts,” he complained.

I was so sleep deprived that his complaint barely registered. “Go back to bed and it’ll be better in the morning,” I mumbled.

Half an hour later, he was back again. Still, he had no fever, and nothing seemed to be wrong, so I let him stay in my bed and prayed for a few hours of unbroken rest.

The next morning he was still complaining that his stomach hurt, and he didn’t want to go to school. This got me worried; Moishe was an active kid who’d been happy to go to first grade every day. Maybe the antibiotics were affecting his stomach? Or maybe (please, no!) he had some unrelated flu? Soon my mind was considering darker possibilities. Could it be appendicitis? Or a growth, chas v’shalom? He seemed to be in real pain.

I schlepped him to the doctor’s office, where the NP assured me nothing seemed to be wrong. But that night again, he woke me several times complaining that his stomach hurt. I went back to our pediatrician. He knew I wasn’t the type to overreact to a few stomach pains, but he still couldn’t find anything wrong. Still, Moishe gave me a hard time going back to school, saying he didn’t feel well, was too tired (well, yeah, me too!), and his stomach still hurt him.

That third night was even worse. He cried all night long. I called the doctor ASAP the next morning, and he told me he’d give me scripts for bloodwork and a CT. Meanwhile, Moishe was curled up on the couch, whimpering. The attacks were coming in waves. He’d be acting fine, then he’d suddenly start screaming and curl up in agony, shrieking that his stomach hurt. Then the pain would subside and he’d calm down.

Now, I looked at Moishe huddled on the couch and noticed there were dark red spots all over his legs. I suddenly remembered that I’d seen faint dots when I’d given him his bath the day before, but I hadn’t followed up on them. His stomach pain had driven everything else out of my mind. Now the spots were much darker and had multiplied.

We raced to our pediatrician’s office and showed him this new development. I could see on the doctor’s face that he was concerned about something specific, but he wouldn’t diagnose anything without further testing. I went with Moishe to the hospital, while my husband went home to take care of the girls.

By the time we got to the ER, I was panicked. The admitting doctor took one look at Moishe and his spots, heard my description of his pain, and immediately diagnosed him. “Henoch-Schonlein purpura, (HSP),” he said. (See sidebar.)

I’d never heard of such a thing.

“It’s not commonly diagnosed,” said the doctor, “but it’s probably more prevalent than just the cases we see here at the hospital, because most cases go unnoticed.”

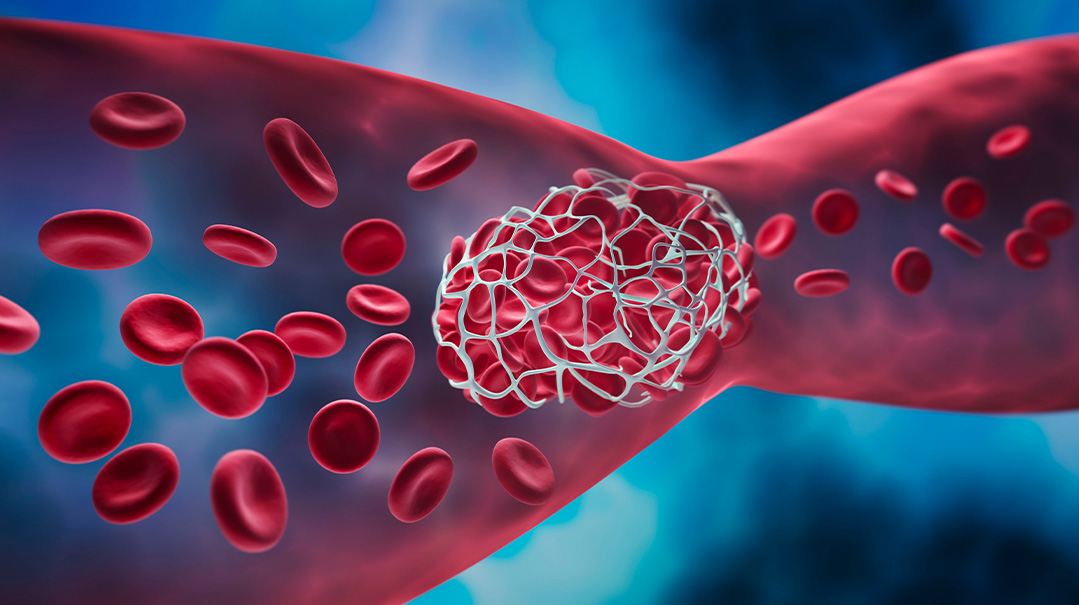

HSP is an autoimmune condition that’s often triggered by a respiratory illness, in Moishe’s case, the strep. Once it attacks the body, it causes inflammation of the blood vessels; the spots all over Moishe’s body were ruptured blood vessels. HSP also tends to attack the blood vessels of the stomach, which is why Moishe had so much stomach pain.

Another potential complication of HSP is intussusception, where part of the intestine twists into an adjoining part of the intestine, causing a serious blockage that can be fatal. Fortunately, an ultrasound of Moishe’s intestines ruled out this concern. The doctor then listed several other complications we’d need to be alert for, before dropping his bombshell. There was no cure for HSP. We had to just let it run its course, and the symptoms and pain could last approximately four to six weeks! And the condition could flare up again at any time for up to a year.

I couldn’t believe I’d heard correctly. How were we supposed to deal with this kind of suffering for so long? Moishe was only a little kid….

But despite my horror, we were on our own, with instructions to use Tylenol or Advil for pain management. The next few days were a nightmare. We’d count the minutes until we could give him his next dose of painkillers. But even with the meds, when a wave of pain hit him, he’d jump out of bed and start running around in agony. He was exhausted and weak but couldn’t settle down at all.

Moishe also couldn’t eat. After sipping even a drop of water, within 30 seconds he’d be shrieking in agony as it reached his stomach. This made giving the painkillers even more difficult as he didn’t want to sip anything that would set off a spasm. Always a skinny child, he became gaunt from the lack of food. It was heartrending.

Twenty-four hours after leaving the ER, I called my pediatrician again in tears. How could we keep this up for four to six weeks? Moishe was in agony and it was progressively getting worse. We tried oral steroids, but they weren’t effective.

We were completely at a loss when my doctor suggested we go to Nemours Children’s Health in Delaware, an hour and a half away. He thought they’d be more likely to admit him for pain management than the hospital close to home. But it was Erev Shabbos, and we had no idea if Nemours would admit us. If we traveled that far and they wouldn’t take us, how would we make it back home before Shabbos? We didn’t have many options, though. We couldn’t stay home like this for Shabbos either. My sister-in-law took the girls, and we packed up as if we’d be staying the whole Shabbos.

Moishe was surprisingly quiet on the drive, and my husband and I looked at each other, feeling cautiously hopeful. Maybe the worst had passed, and we should just turn back and spend Shabbos at home? But the possibility of dealing with another attack was too frightening to risk, and we kept going.

When we got to the triage area, Moishe was still calm. Our pediatrician had called ahead and informed the admitting staff we were coming, but it still took hours in the waiting room until we were actually seen in the ER. As soon as we entered the ER, though, Moishe’s pain returned with a vengeance, and he began shrieking in agony. His screams were heard down the hall.

The staff sprang into action, certain he’d need to be rushed into surgery for his intestines. Thankfully, another ultrasound again ruled that out, and the doctors decided to admit him for pain management. But we had to wait for Covid testing, and it was getting closer to Shabbos. I bentshed licht in the ER, and shortly after that we were moved up to the ward.

Moishe was given a private room, in a brand-new, beautifully designed wing. Parents were encouraged to stay with their kids, and there was enough room for both my husband and myself. There was a whole team devoted to Moishe’s care, with a pediatrician, nephrologist, and rheumatologist, and he was put on an IV drip right away. Just a few hours later, between the strong pain killers he was receiving and the fluids to combat his dehydration, we already saw a difference.

We may have been in the hospital, but we spent a beautiful Shabbos together. It was such a relief to see Moishe calm and relatively pain-free. By Sunday he had stabilized and was able to eat a bit orally, so we were discharged. We returned home in much better spirits, sure that we finally had beaten HSP.

We were soon disillusioned. Within twenty-four hours, the nightmare was back. Moishe was unable to swallow even the slightest bit of medication or food and suffering from horrific debilitating attacks.

On Tuesday, a mere two days after we left the hospital, I was sitting in my bed, and despite my burgeoning stomach, I tried to hold Moishe, vainly attempting to calm him as he thrashed and shrieked in agony. Tears were streaming down my face, but I was trying not to cry out loud because I didn’t want to cause Moishe any more pain. I was at a total loss. I was helpless to protect my child from suffering, and according to the doctors, we still had weeks of terrible pain ahead of us.

“I can’t take this anymore,” I sobbed to my husband. “We have to do something, anything! We have to beg Hashem to take away Moishe’s pain!”

At that moment, we both decided to take on a kabbalah relating to our technology use. My husband ran to our computer and reconfigured our filter then and there. Within an hour, Moishe’s pain subsided. He hasn’t had another stomach attack since.

HSP was a nightmare to live through, but what kept us going were the infusions of kindness. At every turn, we saw how Yidden are there for each other during crises, even total strangers.

During our first ER stay, I was pushing Moishe in a wheelchair down the hall when a girl approached me offering me two bikur cholim meals. I thanked her, but told her I only needed one as Moishe couldn’t eat anything at that point. “Take two,” she insisted. “You may need it for yourself.”

That same stay, we were discharged from the ER at two a.m. Walking with Moishe, I started toward the parking lot when I realized I had no idea where I had parked! I was alone in a huge hospital complex and clueless where to go. Suddenly, as if an apparition, a frum bikur cholim volunteer approached. I must have looked as bewildered as I felt, because he asked me what was wrong. Despite the late hour, he managed to contact the valet system and find my car.

Nemours also has an active bikur cholim room, and the assistant in our pediatrician’s office had called ahead and informed them that we’d need meals for Shabbos. That made such a difference to our Shabbos. And then there was the frum gastroenterologist we’d consulted years before about a different issue. I called him on his personal cell phone to ask about medication for Moishe now, and he was so happy to help me. Mi k’Amcha Yisrael.

It’s been a year since that harrowing experience, all of which was spent in the shadow of HSP. Even after the stomach pain subsided, Moishe also suffered from joint pain and side effects from the steroids — like a bloated, puffy face; aggression; and mood swings — which were all very challenging. The medicine was foul-tasting and it was an issue each day to get him to take it. Plus, he lost a significant amount of weight and was super scrawny and gaunt. I kept reminding myself this too will pass, but it was very difficult for me to see him like this. Throughout the year he was still at risk of recurring attacks and needed constant monitoring of his blood pressure and kidney function. Kidney failure in HSP patients can occur suddenly and without warning.

These potential complications are the reason I wanted to share Moishe’s story. HSP often presents mildly and goes undiagnosed, yet the complications and risks are just as prevalent in a mild case. It’s essential that parents be alert to the symptoms that may present after a respiratory illness and “connect the dots.”

Did you ever have a medical problem that you were told “is nothing to worry about,” and it ended up being a serious issue? Did you have symptoms that stymied doctors? We believe sharing our journeys can bring awareness, empathy, and a sense of connection to those who’ve gone through a medical crisis. If you had a medical mystery and would like to be part of this column, please send a brief description of your story to familyfirst@mishpacha.com

Henoch-Schonlein Purpura

Henoch-Schonlein purpura or HSP (also known as IgA vasculitis) is an autoimmune disorder that attacks the small blood vessels of the skin, joints, intestines, and kidneys, causing inflammation.

Nearly half the people who have HSP developed it after an upper respiratory infection, such as a cold. Other triggers include chickenpox, strep, measles, hepatitis, certain insect bites, and exposure to cold weather. While HSP can affect anyone, it’s most common in children under ten.

For most people, symptoms improve within a month, leaving no lasting problems. But recurrences are fairly common. Plus, HSP carries the risk of complications such as kidney damage (even permanent damage, leading to dialysis or transplants), and intussusception, which can be fatal if left untreated.

The four main symptoms of HSP are:

Rash (purpura), which manifests as reddish-purple spots that look like bruises, usually on the legs and feet but can appear on the face and the rest of the body.

Swollen, sore joints (arthritis), specifically in the knees and ankles. Joint pain can precede the rash by one or two weeks.

Digestive tract symptoms, such as intense stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, and bloody stools. These symptoms, too, can sometimes occur before the rash.

Kidney function can also be affected by HSP, and problems may persist after other symptoms pass.

Information from the Mayo Clinic

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 820)

Oops! We could not locate your form.