Western Light on the Eastern Front

Two of the brothers turned out to be unlikely saviors of Eastern European Jewry during the turbulent years of World War I

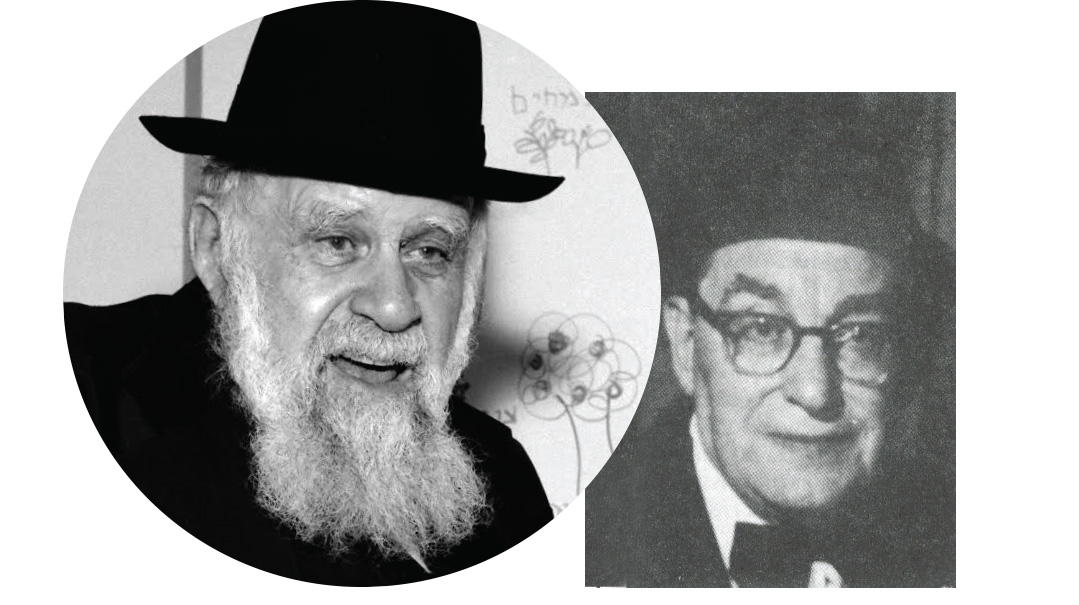

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Family archives

While all 12 children of Rabbi Shlomo and Rebbetzin Esther Carlebach of Lubeck, Germany, excelled in rabbanus, business, and other endeavors, two of the brothers — venerated German rabbiners, turned out to be unlikely saviors of Eastern European Jewry during the turbulent years of World War I

The lights had gone out all over Europe, millions were locked in combat, and World War I was in the process of erasing a generation of young men. It was August 1915, and while the battle on the western front had been reduced to a grinding stalemate, in the east the Kaiser’s spike-helmeted soldiers overwhelmed the Czar’s forces. From Warsaw to Vilna, the feudal Russian overlords were replaced by orderly German administration.

But as Eastern Europeans greeted the conquerors as liberators, farsighted leaders such as the Gerrer Rebbe and the Telsher Rav, feared what the “Deitcher” would do to Poland and Lithuania’s pulsating Jewish life. Because Imperial Germany hadn’t just come to expand its territory. The High Command’s plan to create puppet states on Germany’s borders called for the civilizing of millions of Jews, turning the “wild” Polish Jews into “cultured men,” and replacing the cheder system with German-style schools.

It would be two brothers, both German rabbiners from a venerated family, who would turn out to be unlikely saviors of Eastern European Jewry.

Dignified in the uniform of a German Army chaplain, Rabbi Dr. Emanuel Carlebach, rav of Cologne, was appointed educational adviser to the German occupation forces. And hundreds of miles to the north in Kovno, Lithuania, German authorities appointed a younger brother, Rabbi Dr. Josef Tzvi Carlebach of Hamburg, to the rank of captain with a mandate to reform the school system.

Rabbi Dr. Emanuel Carlebach’s encounter with the Gerrer Rebbe — Rav Avraham Mordechai Alter, known as the Imrei Emes — was a meeting of worlds. In today’s far more mixed religious communities, it may be hard to grasp how far apart the modern German “rabbiner doktor” and the preeminent leader of Polish Jewry were. But the gap was bridged by mutual respect, as the Rebbe had nothing but praise for this different sort of rav who became instrumental in saving Polish chadarim and chassidic life.

And in Lithuania, Rabbi Dr. Josef Tzvi Carlebach gained the trust of the local gedolim of Lithuania, as the young rabbi’s far-reaching educational innovations not only placated the German occupiers, they transformed Torah education in the country long after he’d left.

“If not for your father, all the yeshivos would have closed,” Rav Reuven Grozovsky of Kamenitz later told Rabbi Josef Tzvi Carlebach’s son. He was referring to the critical funds that the rabbi of Hamburg sent to Ponevezh, Mir, and Kletzk when fundraising abroad was halted by the war.

While the Carlebach name is now synonymous with a legend of Jewish music, the large tribe raised by Rabbiner Shlomo (Solomon) and Esther Carlebach of Lubeck was one of prewar Germany’s great rabbinic dynasties. Their twelve “shevatim” were some of Western Europe’s most dynamic rabbanim of the early part of the last century, revolutionizing communities from Berlin to Cologne, Hamburg and Leipzig — up until German Jewry’s agonizing end.

But a century later, the story of two of those brothers, Rabbis Emanuel and Joseph Tzvi Carlebach, is particularly worth telling. In an era when Beis Yaakov schooling and Orthodox political power are facts of Jewish life, both innovations trace their way back, in part, to the Carlebach brothers’ arrival in Eastern Europe. From the existence of modern Torah-orientated newspapers to a girls’ high school in Cleveland, Ohio, the reverberations of their remarkable work still echo on.

One day sometime in the late 19th century in the northern German town of Lübeck, a young boy — one of the Carlebach brothers — arrived late for Shacharis, and hurriedly took his place in shul.

Their father, the town’s imposing rabbi, didn’t say anything about the misdemeanor, because the latecomer’s breakfast plate told its own story. A serving of stern rebuke, his morning roll lay there minus any coveted butter.

But in the family legend, the breakfast table’s educational message didn’t end there. In silent sympathy a few places down, lay Rabbiner Dr. Shlomo Carlebach’s own bread, as dry as his son’s.

More than a century later, that anecdote about the Lübecker Rav is shared by multiple great-grandchildren to explain how a rabbi and rebbetzin from a small town came to found one of prewar Germany’s foremost rabbinical dynasties — and whose descendants continue to grace the Torah world’s mizrach wall.

“My great-grandfather was the image of a Torahdig rav of a typical kehillah of German Jewry,” says the Mir Yeshivah’s Rav Binyomin Carlebach, a grandson of the rav’s son Moshe. “The fact that the Chofetz Chaim could write to him in 1907 offering him the sixth volume of Mishnah Berurah, and referring to him as a ‘m’aor hagadol’ and ‘tzaddik b’maasav’ despite him being a German rabbiner doktor shows the regard in which he was held by the gedolim of Eastern Europe.”

Go into many a Carlebach home, and a portrait of the family patriarch graces the wall. Taken by an anonymous photographer in 1919, the year that he died, the picture is in fact part of a series of three. The first shows Rabbi Carlebach with head bent over a large sefer, his face framed by a high velvet yarmulke and peyos and beard untypical of a German rabbi. In the second frame, his clever eyes gaze to the side, and there’s a smile on his face as he welcomes the newcomer. By the third, the expression is stern as he realizes that he’s been photographed.

“Growing up, I knew little of my great-grandfather,” says Rav Binyamin Carlebach, “because my father was born around the time of his petirah, and didn’t have his own interactions with him. Bu in that photo I can see the typical Carlebach expression.”

Born in 1846 in Heidelsheim, a village in southern Germany, to parents who were well-to-do farmers, Shlomo (Solomon) Carlebach was the only one of six boys to receive a higher Torah education. But if his parents could give him no real learning, they actively worried about his middos.

“His mother was afraid of ayin hara if he arrived in school like a baron in a wagon,” wrote Rabbi Naftali Carlebach, one of the 12 children and father of Shlomo the singer, in his book The Carlebach Tradition. “She was also afraid that he would become haughty, and so the mother’s love compelled her son to go an hour on foot each way, every day.”

For centuries, most German Jews were very similar to those farther east, but in the second half of the 19th century, even the provincial areas of Germany began to change. The traditional Jewish education system gave way to a strong focus on secular studies, even for pious and simple Jews like the Carlebachs. That process led young Shlomo to years of study, first in gymnasium and then in one university after another.

While studying in Wuerzberg, he learned Torah under one of Germany’s great geonim, Rav Seligman Baer Bamberger, known as the Wuerzberger Rav. In a spell in Frankfurt, he became close to another great influence on his life, Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch. Rav Hirsch took the young student under his wing, and discussed with him the battle against the Reform movement.

But despite Rav Hirsch’s fearless battle against the Reformers, he objected to Shlomo Carlebach’s use of the word “poshim” to describe them. “Say rather, our misled brothers or sisters,” recorded Rabbi Naftali Carlebach, “It’s the whole past before him that should bear the burden of guilt.”

(That embracing attitude toward lost Jews filtered down to Rabbi Naftali Carlebach and, as we know, his famous singer son Shlomo. All the Carlebach brothers had a certain comportment as well — it was like a magnet of charisma they all inherited from their father. And like his father and brothers, Rabbi Naftali, who had been a well-known rabbi in Berlin before founding Manhattan’s Carlebach shul, had a real hadras panim, which led to an interesting encounter Reb Shlomo once related to an audience: “My father was once standing at a bus stop in America, and someone stopped and offered my him a ride. When my father asked the driver why he stopped for a stranger, the man replied, ‘Because my wife said you look like G-d.’ ”)

Meanwhile, in the second half of the 1800s, the young Shlomo Carlebach studied in the University of Berlin, eventually graduating with a PhD in German drama, and concurrently learned Torah under the great Rav Ezriel Hildesheimer, known across Germany as “the Rebbe.”

It was Rav Hildesheimer who recommended him for his lifelong rabbinical position in the small northern German town of Lubeck, an ancient community of deep-seated yiras Shamayim. The town’s rav, Rabbi Sussman Adler, had just died, and had left behind a wife, one son, and a daughter. The daughter, Esther, was only 16 at the time, but carried on leading the Jewish school that her father had founded, where she taught Chumash, geography, French, and needlework, among other subjects. When the new rabbi, who was still single, arrived, he made her an offer she couldn’t refuse — and she soon became Rebbetzin Carlebach.

So how did the rabbi of a busy community manage to take care of his duties and educate each one of his 12 children? “Reb Gumpel” is the short answer.

Rabbi Mordechai Gumpel, a student of the Aruch L’Ner, Rav Yaakov Ettlinger, lived in the Carlebach’s house and taught all the children.

“He was a rebbi and madrich to all 12 Carlebach children, from aleph-beis to Talmudic proficiency,” writes Rabbi Dr. Josef Tzvi’s son Rav Shlomo Carlebach, a former mashgiach of Yeshivas Chaim Berlin, and the author of the book Ish Yehudi on his father’s life. “To this day, he remains something of a legend in Carlebach family annals.”

Without the benefit of yeshivah study but with the early help of their house rebbi, five of those eight turned out to be leading rabbanim in Germany. The eldest, Rabbi Emanuel (Sholom Menachem) Carlebach was rabbi in Cologne; Dr. Ephraim was rabbi in Leipzig, instrumental in reversing the ban on shechitah in the state of Saxony; David was rabbi in Halberstadt, before he passed away at a young age. Dr. Naftali (Shlomo-the-singer’s father) was rav for many years in Berlin’s Passauestrasse Synagogue in Berlin, and in his later years established Manhattan’s Carlebach Shul. Rabbi Josef Tzvi was rabbi first in Lubeck, followed by the combined rabbinate of Altona, Hamburg, and Wandsbeck.

Other sons were in business, and of the daughters, three married distinguished rabbanim or lay leaders.

In a way that foreshadowed his sons Emanuel and Josef Tzvi, family patriarch Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, a student of German universities and talmid of Rav Bamberger, Rav Hirsch, and Rav Hildesheimer — who spent most of his life in a quiet German town — came to be well-regarded among Eastern Europe’s Torah royalty, as evidenced by letters sent to him from several gedolim of Eastern Europe.

That respect was evident in a letter that Rav Shimon Shkop penned a letter to Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach in 1922 (he didn’t realize that the Rav had passed away three years before). The Grodno rosh yeshivah pleaded with the German rav to prevail on “his admirers and close circle to support this holy yeshivah that brings blessing and kiddush Hashem in our whole country.”

In those difficult postwar years, with Eastern Europe’s economy shattered by the conflict, it was doubtless one of hundreds of fundraising letters written by Rav Shimon Shkop and other roshei yeshivah, but the letter is still noteworthy for what it tells us about the Lubecker Rav and the stature he had among his East European contemporaries.

“Kevod zekan hador — the elder of the generation, the great gaon and man of many facets,” the Rosh Yeshivah addresses the German rabbi in his impeccable script. The reference to his elder statesmanship goes well beyond conventional honorifics, expected in a fundraising letter of this sort, implying a deep respect. But in those pre-Agudah years, how did that relationship come about?

Perhaps the two worlds met through the Carlebachs’ mechutan. Reuven Zelig Persitz was a Moscow-based tycoon and supporter of the great Eastern European yeshivos. In 1906, Rav Shlomo Carlebach’s son Alexander, who himself became a wealthy banker and supported his rabbinical brothers, married Sonya Persitz. And Sonya’s brother Yosef was a talmid of Rav Shimon Shkop in Telshe.

When the victorious German forces marched into Warsaw, the Gerrer Rebbe knew he had to take action. The appointment of Dr. Ludwig Hass, a Reform Jew and senior member of the occupation authority, was a sign of Germany’s intentions vis-à-vis the Jews: modern Germany versus chassidic Poland.

At an emergency meeting of Polish rabbanim, the Gerrer Rebbe called on the German members of the nascent Agudas Yisrael movement to come to the aid of Polish Jewry. But then, Heavenly help intervened. Rabbi Dr. Pinchas Cohn, rav of Anspach in Germany, visited German administration leader General von Beseler and his advisor Dr. Haas, and suddenly, Ludwig Hass became friends with Rabbi Cohn and made a complete turnaround.

The impression the Orthodox rabbi had made on the liberal official opened the door for another imposing rabbi to join the German administration. Rabbi Emanuel Carlebach, who was already serving as a Jewish army chaplain in Poland, was a man of impressive bearing. “For the Germans,” writes his son Alexander, who was a rabbi in Ireland and in the United States, “his nobility and charm, his bearing and his wide culture came somewhat as a surprise.”

Rabbi Emanuel Carlebach soon found himself appointed, alongside Rabbi Pinchas Cohn of Anspach, to the position of educational advisers to the German occupation.

Dressed in their tailored German Army uniforms, high boots, and military caps, the two were like alien species around the tish of the Gerrer Rebbe, to which they were invited as special guests. Pictures of the rabbis with their trim moustaches and spitz-barts next to the Polish chassidim with their floor-sweeping kapotes conveys the vast gulf in between the German and Polish Jews.

In fact, when the “Deitscher” were honored with shirayim at the Rebbe’s tish, the Rebbe instructed his attendant to bring his visitors cutlery to eat it with, according to one observer whose memories were recorded by writer Aharon Sorasky in Rosh Golas Ariel.

Outsiders they may have been, but the Imrei Emes trusted them implicitly to defend Polish Jewry’s traditions. The two rabbis successfully neutralized the threat to the traditional long garments that chassidim wore, under the guise of a health edict by German authorities. But the long-term threat was to the cheder system.

At a meeting with Poland’s leading rabbanim and chassidic rebbes, Rabbis Cohn and Carlebach warned that the German authorities would ban chadarim entirely if changes weren’t made, including adding two hours of secular studies a day.

In a cheder system that was never formalized and certainly included no secular studies, this was revolutionary, and some were inclined to defy the authorities. Over the opposition of some of those present, it was the Gerrer Rebbe’s support that proved crucial.

In a letter to Rabbi Emanuel Carlebach, the Imrei Emes confirmed his support for their approach to the authorities: “In my eyes, the decision of the rabbanim is correct that Torah studies should be at least six hours, and secular studies not more than two hours and that they should be in the middle of the day.”

The idea of sandwiching secular studies in between Torah learning so as to begin and end the day with learning is something that the Gerrer Rebbe was insistent on, and which framed the curriculum of the new German-sanctioned network of Yesodei HaTorah chadarim that spread across Poland.

Still, for the Rebbe, certain aspects of chinuch were non-negotiable. “He trusts me totally,” Rabbi Carlebach wrote in a letter home in 1916, “…but (insists that) the traditional teaching method of kametz alef ah is not to be touched, saying that when this disappears, all the kedushah of the letters will disappear.”

While the Gerrer Rebbe had great respect for these rabbanim of a different world, what impression did Polish Jewry make on Rabbi Emanuel Carlebach?

Rabbi Alexander Carlebach, a son who served communities in Ireland and the United States, describes the impact of chassidic life on his father. “Whether it was the atmosphere of the synagogue or beis medrash at prayer, with its warm, unreflective enthusiasm and its enchanting melodies, or that of the chassidic Shabbos table exuding a spirit of other-worldly sanctity; whether it was the picturesque chassidic dress and hair-style, all these and more overwhelmed a man of such fine religious and aesthetic sensitivity as Emanuel Carlebach,” writes Rabbi Alexander Carlebach in an introduction to his father’s letters. “More than anything else, it was the familiarity with rabbinic learning of the Polish Jew that provoked his admiration and envy.”

The German-born rabbi’s starry-eyed view of Poland’s Jews, however, lessened somewhat over time as he navigated local Jewish politics, but his admiration for the “vigorous, living forces of Eastern Jewry” never disappeared, even as the rabbiners returned home when German forces retreated from Poland in 1918.

Still, their years in Warsaw saved not only the Polish cheder system, but laid the ground for Orthodox political power that we take for granted today. Because as part of the efforts to represent Polish Jewry to the Germans, the rabbis established the so-called Agudas HaOrtodoksim, an organization that united large numbers of Polish Jews, and that was the forerunner of the post-Word War I Agudas Yisrael. The newspaper they established, Dos Yiddishe Vort, eventually became the long-running Yiddish-language organ of the Agudah.

It’s hard to overstate how important these moves were. Before the advent of these organizations, political power was exercised on behalf of religious Jews by assimilationists of one stripe or other. With the shriveling of the Vaad Arba Aratzos (the “Council of Four Lands”) — a pan-Polish Jewish communal body — in the 18th century, there had been no Jewish political architecture for nearly 200 years.

But as Agudah leader Rav Yaakov Rosenheim later wrote: “Almost all of the elevated people who afterward put effort into building Agudas Yisrael in Poland under the leadership of the Gerrer Rebbe, received their political education under the direct leadership of Rabbi Pinchas Cohn of Ansbach.”

And while Rabbi Emanuel Carlebach returned to Cologne, Polish Jewry had seared into his soul. Until his passing in 1927, wrote his nephew Rav Shlomo in Ish Yehudi, the scenes of poverty and deprivation haunted him.

“He returned home a heartbroken man, never recovering from the pain of commiseration.”

It was 1931, the suffering of World War I was fading into memory, and Hitler was still dreaming of power, when a delegation of West European lay leaders headed by Rabbi Josef Tzvi Carlebach — Rabbi Emanuel’s younger brother — spent a remarkable week in the town of Mir, Poland.

The occasion was the Keren HaTorah study tour, a project of Agudas Yisrael, which aimed to introduce these lay leaders to the worlds of the great yeshivos and centers of chassidic life. After meeting with Rav Meir Shapiro in Lublin, Rav Chaim Ozer, and the Chofetz Chaim, the delegation arrived in Mir.

“Many years later, my father-in-law, Rav Beinish Finkel, recalled Rabbi Josef Tzvi Carlebach greeting then-Rosh Yeshivah Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel each morning,” says Rav Binyamin Carlebach. “With his German manners he would say, ‘Guten morgen, Herr Rabbiner! Wie haben sie geschlafen — How did you sleep?’ ”

The memory of that encounter was passed down. “I used to greet the Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Nosson Tzvi, by saying ‘Guten morgen, Herr Rabbiner! Wie haben sie geschlafen?’ ” Rav Binyamin Carlebach recalls amusedly.

Rabbi Josef Tzvi, called “Uncle Jo” by the family, was the sixth son of Rabbi Shlomo and Esther Carlebach and last to get married, but played an outsized role in the family.

A gifted speaker, magnetic personality, talmid chacham, and born leader, he built Torah schools in Germany and Lithuania, headed major kehillos, was respected by Torah leaders everywhere, and finally sacrificed himself al kiddush Hashem by refusing to abandon his community to save himself at the beginning of the Holocaust.

Like his brothers, he was a talmid of Rabbi Mordechai Gumpel and of his father, but Josef Tzvi’s path diverged early on when he was drawn to Eretz Yisrael a decade before his encounter with Eastern European Jewry. It was 1905, and the young man was studying at Berlin University under the famous physicist Max Planck, when the principal of the Lemel School in Jerusalem — a controversial institution under fire by students of the Maharil Diskin for teaching secular studies — came to recruit a teacher. And so, when Eretz Yisrael was still ruled by corrupt Ottoman authorities, Josef Tzvi headed for the Holy Land.

A product of the “Torah im derech eretz” combination of the rabbinate and university, young Josef Tzvi encountered a different kind of greatness among the perushim of the Old Yishuv. He was particularly taken by the aged rav of Jerusalem, Rav Shmuel Salant. After visiting the Kosel for the first time on a Friday night, he went to Rav Salant’s tiny two-room home in the Old City’s Batei Machseh complex.

“There, on a wooden table bearing two loaves of bread, was a man whose name resounds wherever rabbinic greatness is revered,” he wrote on his return in 1909. “It dawned upon me that I had come face to face with genuine aristocracy, in whose presence the loud bragging of the shallow veneer of our existence must hide its face in shame.”

A bond formed between the young German visitor and the Yerushalmi leader who encouraged him to go about his teaching at the Lemel School (whose historic property on Rechov Strauss today houses the Eitz Chaim yeshivah).

“When he arrived in Jerusalem, Rav Shmuel Salant encouraged him to teach there,” says Rabbi Sholom Menachem Carlebach, Rabbi Josef Tzvi’s grandson. “He explained that the Maharil Diskin’s cheirem on the school was only against sending children there, not teaching there, which could save childrens’ futures.”

He left Eretz Yisrael in 1909, shortly before Rav Shmuel Salant was niftar, but those four years in Jerusalem opened his mind to a totally different genre of Torah living, which, combined with his own masterful teaching abilities and academic studies, would soon transform Jewish education in Lithuania in much the same way as did his older brother Rabbi Emanuel.

German occupation of Lithuania in 1915 brought with it the same threat to the traditional school system. So when Rabbi Josef Tzvi’s brother-in-law, Rabbi Dr. Leopold Rosenak, was appointed an advisor to the German army on Jewish matters, he turned to his gifted young brother-in-law to head a new school in Kovno.

In conjunction with major rabbanim in Lithuania, Rabbi Josef Tzvi, who was just 31 at the time, established separate boys’ and girls’ schools along the lines of the German “Torah im derech eretz” model, combining secular and Torah education. Within three years, the rabbi in the German Army uniform managed to expand the school to a thousand pupils.

“World War I destroyed the traditional community structure, and the generation was disintegrating because there was no girls’ education,” says Rav Aharon Lopiansky, a son-in-law of Rav Beinish Finkel. “He took what Germany had learned and understood that Lita needed it. He had a foot in two worlds, but understood that while the German Jews were better at sculpting the outer body of Yiddishkeit, the neshamah is the Torah that was over there in Eastern Europe.”

The “Carlebach Gymnasium” was so successful that it drew the attention of Rav Yosef Leib Bloch, rosh yeshivah of Telshe, who decided to set up his own school network in consultation with Rabbi Josef Tzvi. Agudah educator Dr. Leo Deutschlander was brought in to head the effort, and ten years later, in 1930, the Yavneh network, as it was known, counted high schools in Telshe, Kovno, and Ponevezh, as well as about 100 elementary schools.

When the Telshe yeshivah was transplanted to America mid-war, the Yavneh name was revived as the name for the affiliated girls’ teachers training college. In that way, the faint echoes of Rabbi Joseph Tzvi Carlebach still reverberate today. Because when he headed back to Germany to resume his rabbinic career, acting as the link between Germany and Lithuania, he had put the concept of the religious high school on the map — a model that we take for granted today.

Rabbi Josef Tzvi returned to Germany briefly to marry Lotte Preuss, whose father Dr. Julius Preuss was an expert on medicine in the Talmud. But it was Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach’s passing in 1919 that brought Josef Tzvi back permanently, taking over his father’s rabbanus in Lubeck. Like his father, he’d earned a special place in the hearts of the Lithuanian roshei yeshivah — including Rav Aharon Kotler and the Ponevezher Rav, who both appealed to his love of Torah to help keep their institutions afloat in the difficult 1920s.

And he very literally took the Torah of Lita back to Lubeck. He arrived back in his hometown determined to establish a regular yeshivah — a rarity for Germany — and with a rosh yeshivah in tow. Rav Shmuel Aharon Rabinov was a leading talmid of Slabodka, and he followed Rabbi Carlebach in the latter’s increasingly senior rabbinic appointments, as he rose to become rabbi of Hamburg and Altona.

In 1931, before Hitler had risen to power, Rabbi Carlebach — by this time one of Germany’s leading rabbanim — made his final trip to the world of the East that he’d come to know and love.

As head of the Agudah’s Keren HaTorah delegation, he was honored by leading gedolim across Eastern Europe. Rav Meir Shapiro of Lublin, both a rosh yeshivah and a member of the Sejm, the Polish parliament, fascinated Rabbi Carlebach, as did the Chofetz Chaim and Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski.

With the rise of Hitler in 1933, the Carlebach family story — like that of German Jewry in general — took a dark turn. Having refused offers to leave Germany as the Nazi menace grew, by the time the war began he was the most senior rav left in the country.

Sent to Jungfernhof, a labor camp near Riga, the man who’d dedicated his life to Torah and Jewish education across Europe didn’t give up even as the end approached. With barely a scrap of paper, and minimal books and seforim, he improvised a school for the children in the camp. Most didn’t have more than a few weeks to live, but they went to their deaths knowing the tunes he’d taught them.

And when he met his end just before Pesach of 1942, along with his family and thousands of others, Rabbi Josef Tzvi Carlebach did so with the matzos he’d baked on the camp stove in his pocket.

While his death brought an end to a remarkable life that managed to consolidate distant Torah worlds, one last symbolic marker of his journey remains.

In Jerusalem’s Har Hamenuchos in November 2011, as the levayah of Mirrer Rosh Yeshivah Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel ended in the chelkas harabbanim, this writer found himself near a matzeivah. It was the grave of Martha Preuss, Rabbi Josef Tzvi Carlebach’s mother-in-law. Lower down, there’s an inscription memorializing the Carlebach family, whose mass grave lies in Latvia.

And so, just a few feet away from the great roshei yeshivah of the Lithuanian world whom Rav Joseph Tzvi Carlebach grew close to, is the eternal memory of his own family.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 854)

Oops! We could not locate your form.