Valley of Echoes

The new cadre of journalists was a little less focused on accuracy and a little more into likes and retweets

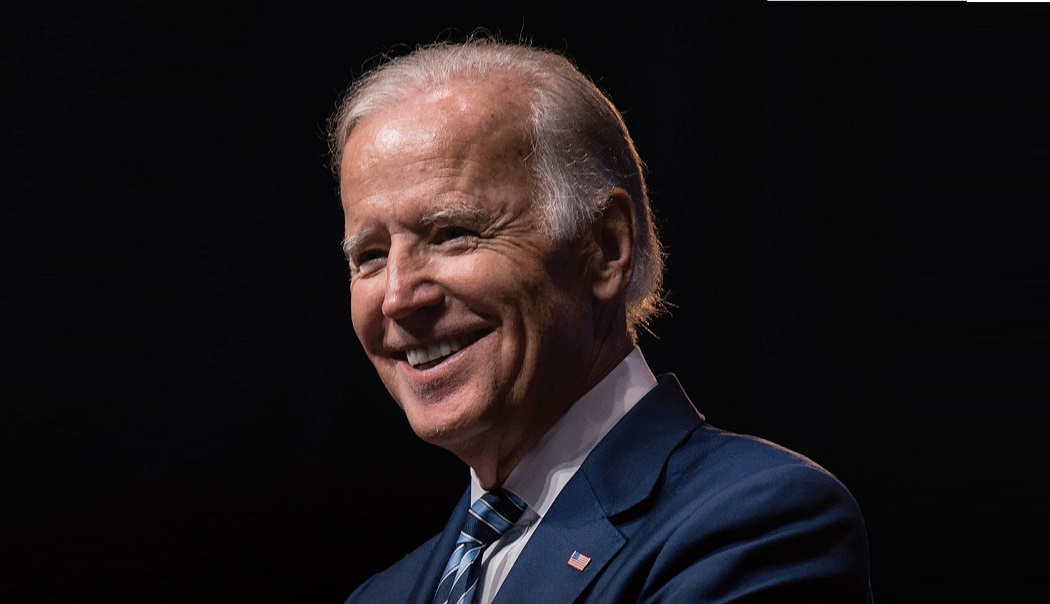

On a riser in the ballroom of the New York Hilton on the night when Donald Trump was first elected, a tripod jammed into the back of my leg, and I overheard a conversation between two journalists in the same section.

It was already after midnight, clear that these results were for real, and most of the people on the risers — reporters, cameramen, sound men — were in acute distress. But one woman behind me was cheerful.

“Listen,” she told a colleague, “for months now, Trump has made us the story, pointing to us and even calling us out by name. If he’s president, then we’ll be news, always. It’s the best thing that ever happened to us. Let’s roll with it.”

It’s rule number one in journalism: You are not the story. But Trump, she was arguing, had made them the story, so why not enjoy it?

Her prediction played out over the next few years with correspondents and journalists, previously unknown, developing national profiles, more than a few of them writing books by cashing in the chaos and commotion to write books.

Perhaps.

But it didn’t really start in 2016.

More than a century ago, Walter Lippmann of the New York World wrote scathingly of how cultural blinders had distorted New York Times coverage of the Russian Revolution.

“In the large, the news about Russia is a case of seeing not what was, but what men wished to see,” he wrote.

Lippmann and others began to look for ways for the individual journalist “to remain clear and free of his irrational, his unexamined, his unacknowledged prejudgments in observing, understanding, and presenting the news.”

A century later and the accusation still lives, perhaps even more acutely than back then.

Because everyone has stopped pretending. Trump doesn’t pretend to like the media, and in exchange, they have stopped pretending to be partial.

Not everyone blames Trump, though.

“I regret to inform you,” says Liel Leibovitz, a senior writer at Tablet, “that the American press has died a tragic death, most likely by blunt force applied to its head sometime ago. Investigations are still afoot, but the likely suspect is the Internet, having robbed news outlets of their main source of revenue, advertising, and ushering in a cheaper, crasser, and far less meaningful system of rewards that praises sound and fury rather than thought and careful contemplation. This presented political operatives with golden opportunities to create their echo chambers, which, in short order, they did.”

The Internet didn’t just make paper maps worthless, but also the old model, hardworking journalist, who researched, networked, called sources, and then filed a story. There were bloggers who moved faster, broke stories on the moment, and their stuff was free, until — ironically — they too were made obsolete, knocked out and replaced by Twitter handles.

The new cadre of journalists was a little less focused on accuracy and a little more into likes and retweets.

Jonathan Kay, senior editor at Quillete, explains what happened next. “It changed how journalists related to each other and the wider world.

“When I started my career in journalism,” he recalls, “I would talk to my colleagues for eight or nine hours a day and then go home and not think about them for the rest of my day. I would go to the gym or hang out with my family or walk around my neighborhood, and generally just conduct my life outside of the world of journalistic ideas. That has completely changed. When journalists now go home, they just switch on their social media and continue being in their same little bubble of professional colleagues, and they never really have an opportunity to let the real world affect them. They have much less opportunity to get the viewpoints of ordinary people.”

The objectivity wasn’t willingly discarded; it was just a lack of interaction with regular people, brought to the fore by the Trump election. Instead of a mocking nickname, “media elites” became a reality, underscoring the idea that well-educated, sophisticated men and women on the Upper West Side of Manhattan had no clue what was really going on in Owensboro, Kentucky.

In his 1986 book, The Media Elite: The New Powerbrokers, author S. Robert Lichter shared a survey revealing that the most of the top journalists in the United States were very similar to each other in background, status, ideology — and very different from the wider public they aimed to serve.

After the 2016 election, the New York Times seemed to have gotten that, pledging to do a better job finding the forgotten Americans and reflecting their views.

I asked conservative thought leader Ben Shapiro, editor emeritus of the Daily Wire and host of the Ben Shapiro Show, how he thought they’d performed on that pledge. “Look, not a single person who voted for Trump works on their op-ed page. And even those who might be kind to Trump supporters are on thin ice.”

There is another reason they are in jeopardy, explains Jon Kay. “The other thing that social media does is it raises the cost for any of these people to have any point of view that is heterodox, because social media acts as a perfect punishment mechanism for anybody who goes outside the group consensus. Back when I started my career, if I wrote something that my colleagues disagreed with, I usually would hear about it in the cafeteria or perhaps in the letters column. Now, I hear about it 24/7, thanks to Twitter.

“Liberal people I know in Montreal and Toronto and New York have curated their Facebook and Twitter followings, so it’s all people who have exactly the same point of view as them. They have come to believe that anybody who thinks differently is crazy or racist or evil.”

The echo chamber isn’t just a function of convenience, but of necessity. Otherwise, the bullying is just too much.

The self-inflicted tone-deafness is just part of it, but there’s another, more sinister part, says a veteran journalist.

“If you don’t know about other viewpoints, and you write anyhow, you’re silly, but if you don’t care about other viewpoints, or worse, have an agenda to squash them, you’re a jerk,” he tells me.

There, he concedes, the right is as guilty as the left.

“There was always an informal understanding that access to a politician came at the price of being kind, so if you wanted to interview Obama, you’d better be gentle. But until Trump, it was never expressed outright, and politicians would engage with ‘hostile’ media to ‘celebrate’ that we live in a democracy. So, for example, Barack Obama sat down with Fox News on Super Bowl Sunday of 2014.”

“Of course we became partial, because it became currency for them. If you could show a positive story you’d filed, you had a good chance of landing a plum interview. It’s always been that way, but it was discussed in whispers, and now it’s being shouted from the rooftops.”

But even with media objectivity gone — or “dead,” as Liel Leibovitz says — last month’s decision by Twitter and Facebook, “big tech,” to obliterate the Hunter Biden laptop story, along with the cooperation of the wider media, shocked many.

To the left, it was just another “crackpot” story, some emails linked to a laptop that may or may not have belonged to Hunter, nothing to see here, move on. But to the right, it was all the evidence they needed to prove that everything was a lie — you see you can’t trust the mainstream media, right?

“In a strange way,” wrote David Harsanyi in the National Review, “the lack of coverage has perpetuated the story, because suppressing it — the New York Post’s Twitter account is still frozen — allows the imagination to run wild.”

“The power of media gatekeepers (like this newspaper) to shape political coverage is still significant,” Ross Douthat conceded in the New York Times, “and just because some charge or scoop circulates in the right-wing ecosystem doesn’t mean that it has any impact beyond the realm of people who are already voting for Donald Trump.”

So where do we go from here? Accept defeat and conclude that objective journalism is dead?

Not necessarily, says Ben Shapiro. We can still hope — but we need to take a pragmatic view of the environment. “I believe there is room for people to strive for objective journalism. But more and more journalists understand that openly pleasing a rooting interest while mimicking objectivity is a sweet spot for them. The media created this environment, and now they’re reveling in it. There are no journalistic ethics anymore. There is only the narrative.”

Liel Leibovitz likewise sees that there are people trying, but they are alone. “There are still a few decent publications struggling against the torrent of nonsense that passes for journalism these days — some of it partisan, all of it idiotic — but they are the exception to a very sad rule. For the most part, American journalists are now members of a class of mutually credentialing mediocrities who have no curiosity about or commitment to anyone beyond their small circle of friends and colleagues, and unless you happen to belong to this small and mirthless gaggle, there’s no reason anymore to take any of them or their work seriously.”

Last week, a stain appeared even on one of the “decent” ones.

Glenn Greenwald wrote on the Substack website of his resignation from The Intercept, the online publication he’d co-founded, explaining why he had to move on from a zone that was meant to be a place for “fearless, adversarial journalism that holds the powerful accountable.”

“The final, precipitating cause,” he wrote, “is that The Intercept’s editors, in violation of my contractual right of editorial freedom, censored an article I wrote this week, refusing to publish it unless I remove all sections critical of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, the candidate vehemently supported by all New-York–based Intercept editors involved in this effort at suppression.

“The censored article, based on recently revealed emails and witness testimony, raised critical questions about Biden’s conduct. Not content to simply prevent publication of this article at the media outlet I co-founded, these Intercept editors also demanded that I refrain from exercising a separate contractual right to publish this article with any other publication.”

Leibovitz’s and Shapiro’s grim assessments of the future and Greenwald’s courageous decision all answer the question, but to me, the most damning statement came from one of the most prominent journalists in America, an author of best-selling political books and a national pundit.

His answer was short, just two sentences.

“These are very good questions,” he said, reading the charges of media bias, and then he said, “but I can’t answer.”

He couldn’t. The price of truth is too high. The price of calling out bias is too high, too pricey for someone who doesn’t want to give up their spot in the club.

So choose your team, America, and settle in for four more years of hearing whatever it is you already believe.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 834)

Oops! We could not locate your form.