Tracing the Maggid’s Footsteps

Rabbi Paysach Krohn may be retiring his bris bag, but after 57 years of milah, he is still using his gifts to bring Jews into the covenant

Photos: Shulim Goldring

The home at 84-09 120th Street was ordinary, its blend of brick and siding looking like any other in Kew Gardens, New York.

But the scene taking place on the inside told a very different story.

Rav Sholom Schwadron, legendary mashpia of the Chevron Yeshivah, stood across from Mrs. Hindy Krohn, seated next to her teenaged son. The widow of the late Reb Avrohom Krohn, niftar just months prior, was voicing pain over her recent loss, and the great Maggid of Yerushalayim was offering words of comfort.

But her son would reveal that the primary subject of their conversation was his older brother, the bechor.

“It’s hard for me to watch Paysach leave yeshivah,” Mrs. Krohn said with a sigh.

She lamented that her oldest son, who had been doing so well in Yeshiva Torah Vodaath, now had to leave to support the family. He had taken over his father’s role as a mohel, but that decision was weighing on him — and it weighed on his mother as well.

When she finished talking, Rav Sholom was quiet. But only for a moment.

“Zurg zach nisht,” he said, “der gantze velt vet noch heren zein Torah.” Don’t worry, the whole world will yet hear his Torah.

Over the years, the reputation of Reb Avrohom Krohn’s son as an excellent mohel would spread. But somehow, as he traveled from bris to bris, a reputation of a different sort would spread as well.

The excellent mohel knew how to write.

The excellent writer knew how to speak.

The excellent speaker knew how to give much needed chizuk and encouragement.

And it’s hard to track when, where, or how it all happened, but Rav Sholom’s brachah began to materialize.

Mrs. Krohn needn’t have worried.

The whole world was hearing her son’s Torah.

Rabbi Nosson Scherman pulled out the pocket phone book from his chest pocket and wrote down the aspiring author’s name. “You’re now one of us,” he said. Years later, the bond holds fast. Rabbi Krohn together with ArtScroll’s Rabbi Nosson Sherman and Rabbi Gedaliah Zlotowitz. It’s a relationship molded by years of hard work, dedication, and deep mutual respect

Interviewing Rabbi Paysach Krohn is an exercise in nostalgia and involuntary inspiration while trying to stay focused on his words in the present. As he speaks, the mind travels, way, way back, to an old gray station wagon, stocked with diligently labeled cassettes.

“And they yelled, ‘Shaya, run to first!’ And Shaya ran to first. And then they yelled, ‘Shaya, run to second!’ And Shaya ran to second.”

We were so young then, decades away from appreciating the lectures our parents enjoyed. And yet, somehow, that speech penetrated, we comprehended it fully.

It was about a child with special needs named Shaya who wanted to play baseball, although he didn’t really know how. Nonetheless, the boys on the field ensured that he scored a home run.

The bat made contact, and neither the pitcher nor the catcher bothered to field the easy out. Instead, Shaya’s teammates cheered him on to first base. They could have settled for the single, but they opted to continue, urging Shaya on to second, then to third. Finally, Shaya ran home, and his teammates erupted in joy.

We understood the message. We were young, but we understood it. And decades later, it continues to resonate.

As that familiar voice speaks, I must force my attention to the here and now, to the inspiration behind the inspiration, the story behind the stories.

True to form, Rabbi Krohn kicks off the conversation with yet another story.

“Several years ago, I went to visit the Me’aras Hamachpeilah,” he says. “I didn’t realize this beforehand, but there are different entrances into the Me’arah, and I entered via the ohel of Yaakov Avinu. I davened by Yaakov, and I was fine. I then davened by Yitzchak, and I was fine. But then I got to Avraham Avinu, and I just burst out crying. I couldn’t understand why, but I was overwhelmed with emotion.

“But then I realized,” he continues, “that, first of all, my father’s name was Avrohom. Second of all, Avraham Avinu was the first mohel. And the third thing I realized was that Avraham Avinu was the first kiruv professional as well.”

For the past 57 years, Rabbi Krohn has served as a mohel, performing brissim on thousands of Jewish children around the globe. It’s a trade that he learned from his father, Reb Avrohom, and assumed after his father’s passing. Rabbi Krohn was only 21 years old at the time.

Many of the brissim that Rabbi Krohn performs are for children from nonreligious families. At these events, his role takes on a dual significance: He must fulfill the mitzvah of milah, but he also must awaken a level of reverence and solemnity among the family and attendees.

“I always request in advance that the parents of the baby speak at the bris,” Rabbi Krohn says. “I ask them to discuss the meaning and significance of the baby’s name.

“I was once doing a bris for a very wealthy family. It was being held in a hotel in Manhattan. I had asked the father of the baby to speak. He got up and began, ‘I was robbed of part of my childhood.’ He explained that his father’s parents and his mother’s parents couldn’t get along. This made it impossible to have an event or occasion where both sides of the family could attend.

“‘Now, it’s time for closure,’ he said. ‘I’m naming this baby after my father’s father and my mother’s father. We’re going to bring the family together.’”

There wasn’t a dry eye in the room. It was one of the many instances where Rabbi Krohn managed to instill a tone of holiness that would extend well beyond the bris itself.

“Whenever I do a bris for a nonreligious family, I share a few words as well,” he says. “I speak about the beauty and importance of raising a Jewish child.”

And then, a few weeks later, he sends the family a booklet with the title Your Son, and the child’s name inscribed below. The booklet contains a write-up about what it means to raise a Jewish child.

For Rabbi Krohn, bris milah and kiruv rechokim are synonymous with each other. And he owes his accomplishments in both of these fields to his father, Reb Avrohom.

When Rabbi Krohn stood before the kever of Avraham Avinu, he wept.

Perpetuating a legacy is an emotional thing.

Regardless of age or stage, Rabbi Krohn’s heartfelt messages penetrate. “I would never speak about something that I myself couldn’t act upon,” he explains. Here he stands with a group of bochurim following a talk given in Far Rockaway’s Yeshivas Shaarei Chaim. To Rabbi Krohn’s right is his grandson, Binyomin Perlstein

“I have been a mohel for 57 years,” says Rabbi Krohn, “and, now, I’m moving on to focus more on my writing and speaking. Baruch Hashem, I have a son and son-in-law who are taking over for me. Fifty-seven is gematria ‘zan,’ which means ‘nourish.’ I feel nourished and satiated by my years as a mohel.”

Having traveled from Bermuda to Puerto Rico to Eretz Yisrael and beyond, Rabbi Krohn’s milah equipment has seen its share of transoceanic journeys. And each comes with its own story.

“I was once called on a Thursday night to perform a Shabbos bris on the West Point army base,” Rabbi Krohn shares. “What happened was that the family wanted a doctor to perform the circumcision. But Mrs. Debbie Schwartz, the wife of a Jewish captain named Billy Schwartz, convinced them to use a mohel instead.”

Rabbi Krohn spent that Shabbos on the army base and performed the bris. While there, he learned that the Schwartzes had one child, but many years had passed and they hadn’t had any more children.

Rabbi Krohn approached Billy Schwartz. “Captain,” he said, “in the merit of your ensuring that this baby had a kosher bris, I’m giving you a blessing that, one year from now, you should have a baby boy.”

One year later, Rabbi Krohn was back at West Point, performing a bris on an eight-day-old baby born to Captain Billy and Mrs. Debbie Schwartz.

But the nearly six decades of such success does little to dispel the memories of his career’s painful genesis.

“My father was a mohel, but in the summer of 1965, he was diagnosed with a terrible disease. By January 1966, it was difficult for him to perform the brissim alone, and I had to go along with him.

“I would show up at yeshivah whenever I could, but I often couldn’t be there for the full sedorim,” Rabbi Krohn says heavily. “It was the hardest year of my life.”

Over the year, Reb Avrohom’s condition worsened, and, on Shemini Atzeres, he passed away. A wife and seven children mourned bitterly.

They weren’t alone. Some five thousand miles away, the legendary mashpia of the Chevron Yeshivah mourned as well.

Reb Sholom Schwadron was the unlikely best friend of Reb Avrohom Krohn. A few years earlier, Reb Avrohom had received cassettes featuring Reb Sholom Schwadron’s shmuessen. Enraptured by the dynamic maggid, he would listen with complete absorption to any recording he could get his hands on. In 1964, Rav Sholom came to America for several months to collect funds for Chinuch Atzmai, and Reb Avrohom insisted that he stay in the Krohn home. Thus developed a soul-deep relationship between the two.

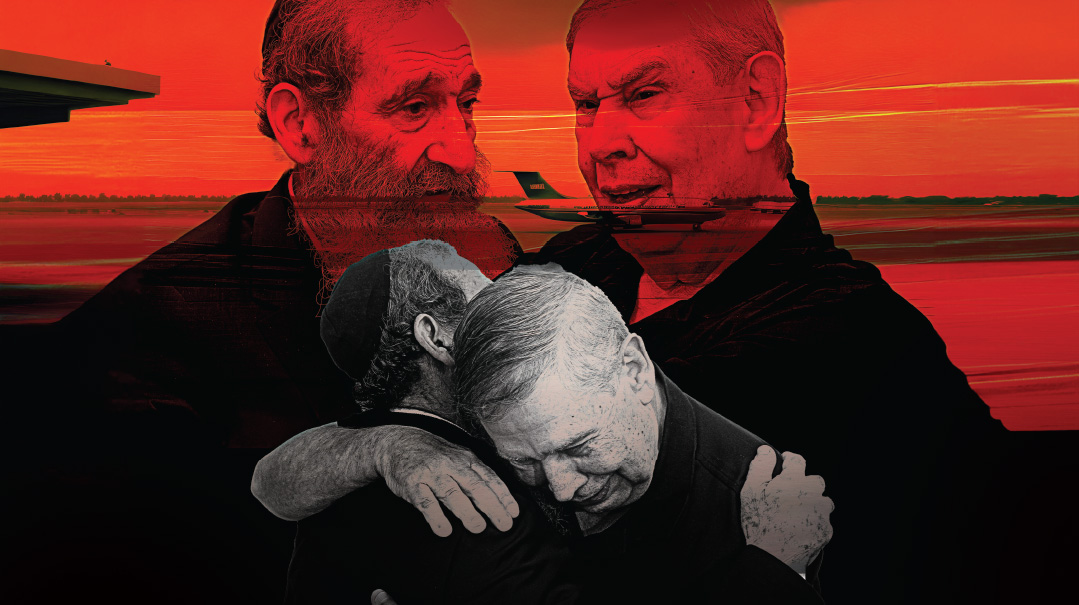

“A few months after my father passed away, Rav Sholom came to America by boat,” Rabbi Krohn recalls. “I went together with my mother and my brothers to the pier to pick him up. When he looked at us, and saw how my father was missing, he just broke down.”

The great maggid didn’t need to say anything to communicate the extent of his pain.

Rabbi Krohn describes the scene in the introduction to his first book, The Maggid Speaks. “One of the greatest sentences I ever wrote was, ‘And the man of a million words had none, the anguished expression on his face said it all.’”

It was on that trip that Rav Sholom paid the Krohn home a visit and consoled the distressed Mrs. Krohn. And in a single sentence, the man of a million words said it all.

“Zurg zach nisht, the whole world will yet hear his Torah.”

“Don’t worry, the whole world will yet hear his Torah.” Rabbi Krohn stands with a group of boys in South Africa

For Paysach, leaving Torah Vodaath as a young adult meant leaving the only life he had ever known.

Although he was born in Williamsburg, Paysach, along with his family, moved to Kew Gardens when he was still very little. “My father was a mohel and there were already so many mohalim in Brooklyn,” he explains. “We moved to Kew Gardens, where the market was less flooded. My father got a job as an on-site mohel in Terrace Heights Hospital.”

His parents enrolled him in Yeshiva Torah Vodaath, which was located in Williamsburg at the time. That meant a train ride to school each and every day. “I was in Torah Vodaath for my entire schooling,” says Rabbi Krohn. “From first grade up until when I left at age 21.”

When it came time to depart Torah Vodaath, Paysach Krohn officially took on the title “mohel.” Now, all he needed was newborn Jewish baby boys to turn the title into a job.

“There was a fellow in my shul named Akiva Wolfson,” says Rabbi Krohn. “I knew that he was expecting a simchah, and I was terrified that it would be a baby boy and that he wouldn’t use me. He was a member of my own shul — using a different mohel would be an open statement that I was considered unqualified.”

One day, Mr. Wolfson approached Paysach. “If it’s a boy,” he said, “it’s yours.”

“That gave me so much chizuk,” Rabbi Krohn remembers. “He gave me the confidence I desperately needed.”

A few weeks later, the Wolfsons celebrated the birth of… a baby girl.

“It was the best bris I never did,” Rabbi Krohn laughs.

But at this point, Rabbi Krohn was facing a different problem. He was of marriageable age, and finding a shidduch was proving to be difficult. “When people heard of a boy who was already working to support a mother and six siblings, they would quickly grow uninterested,” says Rabbi Krohn.

He was 24 years old when he was redt to Miriam Bryks, the daughter of Rav Eliezer Bryks, a talmid chacham and rav in Denver, Colorado. “We got married on a freezing cold February day. The wedding was in a shul but it had no open ceiling and so the chuppah was held in a basketball court across the street.”

“My wife is a tremendous mechaneches,” says Rabbi Krohn. “She is the limudei kodesh principal and a popular teacher at Shevach High School in Queens.”

Chinuch is a primary value to both her and Rabbi Krohn, and that has guided their children into the field of chinuch as well. All their daughters and daughters-in-law are teachers; their first son-in-law, Rabbi Shlomo Dovid Pfeiffer, is a known mechanech and the segan menahel of the Yeshiva Ketana of Long Island; their oldest son, Rabbi Avrohom Zelig Krohn, has been a maggid shiur in Yeshiva Ateres Shmuel in Waterbury for more than 15 years and gives shiurim on Shas illuminated. Their son-in-law, Chananya Kramer, heads Kol Rom Multi Media and has done many Torah projects with Rabbi Krohn, including Living Lessons for Torah Umesorah, which has been seen by more than 10,000 children around the world. Rabbi Ephraim Perlstein is a noted accountant and mohel who also delivers popular shiurim in his office. The youngest son, Rabbi Eliezer Krohn, is the rav of Beis Medrash Ahavas Torah in Passaic-Clifton, as well as a posek for PUAH, an organization that provides halachic guidance to couples struggling with infertility.

Mrs Krohn’s influence guided her children, but, Rabbi Krohn posits, his own success is duly accredited to her as well.

“It would be impossible for me to do what I do without her,” says Rabbi Krohn, “I always say that my wife knows where everything is, and I know where she is.”

After the wedding, the couple settled in Kew Gardens, just two blocks away from the home in which Rabbi Krohn was raised. The new responsibility of having to support a wife in addition to his mother and siblings was burdensome, but Hashem smiled upon his efforts. He was becoming a very popular mohel.

“I’ve been with my father to dozens of brissim,” says Reb Eliezer Krohn, “watching him do a bris is like watching a master pianist as his fingers grace the keyboard. He’s always in complete control. His bandaging of a bris is a masterpiece.”

Today, Reb Eliezer lives in Passaic, where, aside from many other rabbinic responsibilities, he is a much sought-after mohel as well. He follows in his father’s footsteps — quite literally. “My father once had a bris on Yom Kippur, about three miles from our shul. We walked there and back in our sneakers.”

But if he saw his father’s path as one worthy of following himself, it may well be because Rabbi Krohn’s job as a mohel never overshadowed his family responsibilities. In fact, it often complemented them.

“What’s more important, Torah d’yachid or Torah d’Rabim?” Rabbi Krohn asked Rav Dovid Cohen. With time he learned to straddle both pursuits. With Rav Yitzchak Zilberstein

“I remember once, when I was a kid,” says Reb Eliezer, “I was playing in the championship of little league baseball. My father had a bris and couldn’t make it to the game. But he managed to show up at the end, right as the other team made the final out. For years, I had a picture of my father, in his hat and jacket, still holding his milah bag, which he never left in the car, standing with his arm around me, celebrating my victory.”

Attending his father’s brissim allowed Eliezer to learn valuable lessons in the trade of milah that he remembers until today.

“I was at a bris with my father, and I had something scheduled immediately after. But the proceedings were taking longer than anticipated, and I kept looking at my watch. When the bris was over, my father and I left and headed for the car. Then, my father turned to me and said, ‘When you’re at a bris, you can’t look at your watch. For this family — it’s a very special occasion! You have to show them that you share their simchah. That for you, too, this is a special moment.’”

Reb Ephraim Perlstein is Rabbi Krohn’s son-in-law and a popular mohel himself. He received a similar, if not more demanding, directive. “My father-in-law told me never to yawn at a bris. He said that he once accompanied his father to a bris and yawned during the proceedings. The baby’s grandmother chastised his father — ‘How can your son yawn at my grandson’s bris?!’ The idea is to always be aware of your surroundings.”

That Rabbi Krohn’s son-in-law serves as a mohel is not a coincidence.

“By observing my father-in-law, I understood what a rewarding profession milah can be,” says Rabbi Perlstein. “I was living in Eretz Yisrael when I decided that I also wanted to be a mohel.”

Rabbi Perlstein called Rabbi Krohn, who arranged that his son-in-law be able to follow an Eretz Yisrael-based mohel from bris to bris and gain the training he needed to become qualified for the job.

“My father-in-law always wanted to perfect his milah skills,” Rabbi Perlstein explains, “and so whenever he came to Eretz Yisrael, he would observe the Israeli mohalim. That’s how he knew whom to connect me with.”

Rabbi Ephraim Perlstein and Rabbi Eliezer Krohn are links in a very long chain; Krohns have been serving as mohalim for six generations at this point.

“I was once a mohel for a baby, and my father was the mohel for the baby’s father, and my grandfather was the mohel for the baby’s grandfather,” says Reb Eliezer.

But it really goes even farther back; Rabbi Krohn’s role as a mohel seems to have been destined all the way from the start of time.

“I was once paying a visit to a shivah home, and the husband of one of the aveilim approached me,” Rabbi Krohn recalls. “He said, ‘In your milah book, do you have all the Baal HaTurims about bris milah?’ I told him that I thought I did. And he responded, ‘I think you missed one.’”

The fellow then pointed to a pasuk at the beginning of Bereishis. Hashem saw the light and that it was good, the pasuk says: “Vayaar es ha’or ki tov.” The Baal HaTurim comments that the final letters of the words “es ha’or ki tov” spell “bris.”

“I was blown away,” says Rabbi Krohn. “I hadn’t seen that one yet. But then the man said, ‘Wait — there’s more! The words es ha’or ki tov are gematria Paysach Yosef Krohn.’ ”

Rabbi Krohn is proud that his children will be perpetuating his life’s work. But more importantly, he is proud that they are perpetuating the legacy of the very first mohel.

The very first kiruv worker.

And the namesake of his father.

The good light will continue to illuminate.

Rabbi Nosson Scherman would stand and watch with amazement as Rabbi Krohn easily connected with a staunchly chassidishe family. In conversation with the Tolner Rebbe

There’s a fourth commonality with Avraham Avinu that Rabbi Krohn doesn’t mention. Avraham Avinu was the first maggid. Traversing the known world to spread the ideals of a single supernal Creator, Avraham succeeded in speaking to, and inspiring, the masses.

It’s no wonder that Rabbi Krohn might weep at his kever. But, Rabbi Krohn explains, even his career as a world-renowned speaker and writer is owed to his experience as a mohel.

“In 1976, ArtScroll came out with Megillas Esther” he says. “And I loved to write, I wished I could write something for ArtScroll.”

About a year later, Rabbi Krohn met Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz, founder of ArtScroll Publications.

“‘What can I write for you?’” he asked.

“The five Megillos are covered,” was Rabbi Zlotowitz’s response. “But you can choose any text you want, write it up and we’ll publish it.’”

Rabbi Krohn played with a few ideas, but then came a eureka moment.

“I began noticing how ArtScroll had moved on from Megillos and were now publishing seforim on topics. They had put out seforim on Shema, Kaddish, the Aseres Hadibros. I said to myself, ‘If they’re writing on topics, then why not have a sefer about bris milah?”

Rabbi Krohn submitted the idea to Rabbi Zlotowitz. “He gave me the go-ahead along with the following directive. ‘You have no deadline on this sefer,’ he said. ‘But whenever you finish it, it must be done in a way that no one would think of writing an English sefer on milah for the next twenty years.’”

Rabbi Zlotowitz was expecting a sefer that would be fully comprehensive, and Rabbi Krohn was committed to making that happen.

“I discussed it with my mother, she was a very talented writer — I learned how to write from her.” Rabbi Krohn’s mother, Mrs. Hindy Krohn, had never attended a Beis Yaakov, but, in Rabbi Krohn’s words, she was “the frummest person I ever met.” In 1989, her widely acclaimed book, The Way It Was, was published by ArtScroll.

Rabbi Krohn and his mother contemplated the various possible formats for the book. “We felt that it would be best to begin by working off of a text,” Rabbi Krohn relates. “We decided to work off of the tefillos, composed over the centuries, that are to be said at a bris.”

True to Rabbi Zlotowitz’s instruction, the book covered everything. There are sections on halachah, medicine, names, and so on.

“The section on names,” says Rabbi Krohn “is my favorite.”

There is even a section on the spiritual significance of the number eight.

The number eight, Rabbi Krohn writes, appears as a central theme in so many areas of Torah. The bris milah is performed on the eighth day, tzitzis has eight strings per corner, the Kohein Gadol wears eight garments, Dovid Hamelech’s harp had eight strings, and the list goes on. Why is this? What is the significance of the number eight?

Rabbi Krohn explains: A week is seven days; the shmittah cycle is seven years; there are seven heavens… and King Solomon wrote that there are seven pillars of wisdom (Proverbs 9:1). In the physical world, a cycle, a full measure, is seven. In the metaphysical, the higher spiritual plane is represented by eight… The number eight is unique because it hovers beyond the natural.

Rabbi Krohn completed the book and submitted it to ArtScroll. “I remember meeting with Rabbi Nosson Scherman, general editor of ArtScroll. He took out his pocket phone book which was in his chest pocket and wrote down my name. ‘You’re now one of us’, he said.”

“The phone book was in his chest pocket — right next to his heart,” Rabbi Krohn reflects. “I always saw such symbolic significance in that.”

The book, titled simply Bris Milah, was published in February 1985 and enjoyed rapid popularity. It was now growing apparent that the fingers that deftly handled a milah blade could wield a golden pen as well.

Even as Rabbi Krohn was writing the bris milah book, the idea for his next project had occurred to him. He was exceptionally close to Rav Sholom Schwadron, who had an unparalleled repertoire of stories, and Rabbi Krohn was among the few privy to this treasure trove. What if he were to write up these stories and compile them into a book? He approached Rav Sholom and presented him with the proposal. Rav Sholom was exuberant and wanted to begin right away.

After finishing the bris milah book, Rabbi Krohn spent the next year diligently listening to, transcribing, and writing up Rav Sholom’s stories. In February 1987, Jewish book shops displayed the new volume with its intriguing title, shortly to become a history-making series: The Maggid Speaks.

Shortly thereafter, Rabbi Krohn received a phone call from Rabbi Boruch Grossman, the menahel of a local Russian boy’s elementary school. “Would you be interested in speaking at our graduation ceremony?”

“They must have figured — if I can write a story, I can probably tell one as well,” Rabbi Krohn explains.

Rabbi Krohn spoke and the people listened. They went home and told their friends about the wonderful speech they heard. And pretty soon it was apparent: The man who wielded a golden pen possessed a silver tongue as well.

Offers for speaking engagements began in a trickle, soon bursting into a flood.

But even as he would begin accepting a plethora of speaking engagements, he continued to write. Today, he has published 18 books, 16 of which have “Maggid” in their title.

“Rabbi Zlotowitz understood that the term ‘Maggid’ catches people’s interest,” Rabbi Krohn explains.

At first, the term referred to Rav Sholom but, later, it became a reference to Rabbi Krohn himself.

“It takes approximately two and a half years to write a book,” says Rabbi Krohn. “I look for stories that have a lesson that everyone can learn from. My standard is that every story should be at least one person’s favorite.”

His life had now taken on a trajectory that would lead to days jammed with brissim, book writing, and speaking engagements all over the world.

As the acclaim grew at a dizzying pace, so did the demands on Rabbi Krohn’s time.

“He’s the busiest man and has the time for everything,” says Rabbi Yaakov Salomon, a close friend of Rabbi Krohn’s. “It’s hard to understand how it’s possible.”

But for the mohel par excellence, limitations are of little concern. In the world of eight, anything is possible.

Always a talmid. Something that everyone can learn from Rabbi Krohn is that even at his age and stage, he still has a rebbi. He has been learning with Rav Dovid Cohen b’chavrusa for some forty years. At a bris with his long time rebbi and chavrusa, Rav Dovid Cohen, and ArtScroll’s president Rabbi Gedaliah Zlotowitz

AS the years went by, Rabbi Paysach Krohn’s speeches developed their own patented style: deeply emotional, replete with very relatable messages, each delivering practical takeaways. The themes varied, but not significantly; their focus was generally on either chesed, tefillah, or ahavas Yisrael. But, Rabbi Krohn explains, every speech he gives has one common denominator: He believes in its message.

“I would never speak about something that I myself couldn’t act upon,” he says.

Another key to his success comes from the massive amount of preparation that comes with each speech.

“Someone once asked me if I’m scared when I speak,” Rabbi Krohn recounts. “I told him no — I’m scared when I prepare.”

That sense of fear must be far from fleeting because the time he invests in preparation is extensive. “It takes me weeks to prepare a speech,” says Rabbi Krohn.

It’s not just a matter of finding quality material; for Rabbi Krohn, innovation and inspiration are critical factors in a successful delivery. “Any idea shared in a speech must be something the people haven’t heard before. And the story, or the Chazal, has to inspire me. If I don’t feel inspired, then I won’t be able to inspire others.”

But there’s another, less formal form of preparation that has been some four decades in the making.

“Something that everyone can learn from Rabbi Krohn,” says Rabbi Nosson Scherman, “is that even at his age and stage, he still has a rebbi. He has been learning with Rav Dovid Cohen b’chavrusa for some forty years.”

Rabbi Krohn takes this chavrusashaft very seriously, and it has only helped his career. Rav Dovid Cohen, a revered posek who has authored many dozens of seforim, learns together with Rabbi Krohn weekly, and often during these sessions, an idea that will ultimately become the focal point of one of Rabbi Krohn’s future speeches is formed.

But more fundamentally, in a sense, Rabbi Krohn owes his whole career to Rav Dovid.

“When I was considering writing my book on bris milah, I was concerned that it would take too much time away from my learning,” says Rabbi Krohn. “I posed the question to Rav Dovid. His response was classic. ‘What’s more important,’ he said, ‘Torah d’yachid [the Torah of an individual], or Torah d’rabim [the Torah of a multitude]?’”

Rabbi Krohn understood and went on to invest his time in Torah d’rabim.

The preparation is intense, but the written notes he brings along to the event are relatively scant. “I don’t write down every word I’m going to say,” Rabbi Krohn explains, “because, for me, a speech is a conversation. I need the words to flow out naturally. I want to connect with the people.”

A highlight of Rabbi Krohn’s career is when he has the opportunity to travel to Eretz Yisrael in the summer and speak before an audience of 3,000 women, packed into Jerusalem’s Binyanei Ha’umah, in the days leading up to Tishah B’Av.

“When I came the first time, the lights were all off, with only one spotlight shining on the speaker’s podium,” Rabbi Krohn recalls. “I went over to the maintenance people working backstage and asked them to turn on the lights.”

“This is not about me,” Rabbi Krohn explained to them, “the lights shouldn’t be on me.”

The lights were turned on and the speech — or the conversation — continued as scheduled.

The connectivity is a central element in the speeches’ impact, but there are other factors as well — chief among them the blazing force of emotions.

Rabbi Krohn’s speeches are a kaleidoscope of feelings; his voice will rise in joy, tremble with fear, and echo with passion. But the sentiment that emerges as the most notable strain is sympathy: Rabbi Krohn feels others’ pain. And it is precisely that ability that brings about Rabbi Krohn’s fourth, albeit unofficial, career.

As time went on, it was becoming obvious that the silver tongue and golden pen came with a heart to match; the private acts of chesed would soon outnumber the many public addresses.

“Years ago, my father-in-law came to visit us in Baltimore,” son-in-law Reb Chananya Kramer shares. “That week, there had been a terrible tragedy in the community — a rebbi had passed away suddenly on a Lag B’omer trip with his talmidim.”

Rabbi Krohn found out about this and asked his son-in-law to take him to the family’s home. It was Shabbos, there would be no formal nichum aveilim, but Rabbi Krohn wished to deliver words of comfort in the way that only he could.

“We headed over to the home. My father-in-law walked in and sat down to talk with the family. He shared his own life’s story, the pain of losing his father at age 21.”

The family was visibly moved by the genuine care and thanked Rabbi Krohn as they bid him farewell.

But that goodbye proved ephemeral. “My father-in-law kept up with one of the sons,” says Reb Chananya, “for years, he would send him letters or speak to him on the phone.”

For hundreds of people, this comes as no surprise. They too have received the letters, some daily, some weekly, and they run to get the phone when they know that Rabbi Paysach Krohn is calling.

“He has stacks of cards on his postcards on his desk,” says Rabbi Yaakov Salomon. “And notes with people’s full Hebrew names so that he can daven for them. It never ends. He remembers the name of anyone who ever expressed a difficulty they are going through and he always has what to say to them.”

“When it comes to helping a Yid going through a tzarah, he simply has no bechirah,” Rabbi Salomon posits. “He has to reach out and help.”

It is not the sort of sympathy that comes from a purely humanitarian source; it flows from a singular pocket of love. Reserved for one child of Avraham Avinu to another.

“If I were to describe Rabbi Paysach Krohn in one phrase, it would be ahavas Yisrael,” says Rabbi Salomon.

That love extends to all denominations.

It began with writing stories and evolved into telling them as well. Every conversation with Rabbi Krohn is replete with inspirational insights. In conversation with Breslover mashpia Rav Mota Frank

As Rabbi Krohn’s editor for many years, Rabbi Nosson Scherman has become another very close friend of his.

“I was once in Gateshead with Rabbi Krohn,” he says, “and we were approached by someone who informed us that there was a chassidishe family who had just lost their father. I went to the home together with Rabbi Krohn and watched with amazement at how deeply he felt their pain and how strongly he related with them. The family was entirely chassidish, Rabbi Krohn grew up as the typical American boy, and yet he was able to connect with them so naturally.”

There are prisoners in jail who have little contact with anyone in the outside world other than a regularly received postcard. Though they’re not all necessarily as appreciated as Rabbi Krohn would hope.

“There were two prisoners that I would send postcards to,” says Rabbi Krohn, “and I once went to visit them. One of them said, ‘Rabbi Krohn, I don’t have the words to thank you. Your letters are my lifeline.’

“The other fellow said ‘Rabbi Krohn, I hate your postcards. Please stop sending them to me.’ I said – why?! He responded, ‘Because here I am, stuck in jail, and you’re writing me letters from all over the world! I can’t stand it!’”

There’s a young boy who has close to fifty shot glasses, each depicting a different miniature cityscape. There is no logical pattern running through the collection, other than that each depicted city has been visited by Rabbi Paysach Krohn. “I met a boy from a divorced family who could use some chizuk. So, whenever I went to a new city, I bought a shot glass from the souvenir shop,” Rabbi Krohn says simply.

Thursday nights find Rabbi Krohn hunched over seforim as he researches topics on the week’s parshah. He’s preparing, but not for a speech of any conventional sort.

“I am involved in an organization called Links,” says Rabbi Krohn. “Links provides support for children who’ve lost a parent. Each Thursday night, I record a two-minute devar Torah, followed by a brachah — yesimcha Elokim for the boys and yesimeich for the girls. I also record for an organization called Naaleh, which is a London-based version of Links that I helped to found.”

The night doesn’t end there.

“I’m also involved in an organization called Sister to Sister, which, among other support services for Jewish divorced women, also provides support for their children.”

The devar Torah Rabbi Krohn shares on the Sister to Sister hotline is the same as the one on Links and Naaleh, but the introduction for each is different. “And so I make three separate recordings,” Rabbi Krohn explains.

But the Thursday night recordings happen late at night, sometimes after midnight, and that is because Rabbi Krohn has other responsibilities to tend to.

“About ten years ago, my newly married granddaughter and her husband, Reb Moshe Dov Heber, called me and said they wanted to talk.”

A meeting was arranged and the couple shared what was on their minds.

“Zeidy,” they said, “the whole world hears from you. We want to hear from you as well.”

Rabbi Krohn took their words to heart, and a weekly Thursday night “Zeidy conference call” for all the Krohn children and grandchildren was arranged.

But striking the right work-life balance has always been a top priority for Rabbi Krohn. Today, his travel schedule can see him in multiple cities in a single week, but that’s only because his children are all adults.

“There’s no way I would do this while my kids were growing up,” he says. And when he did travel, he always made sure to bring a child or two along with him.

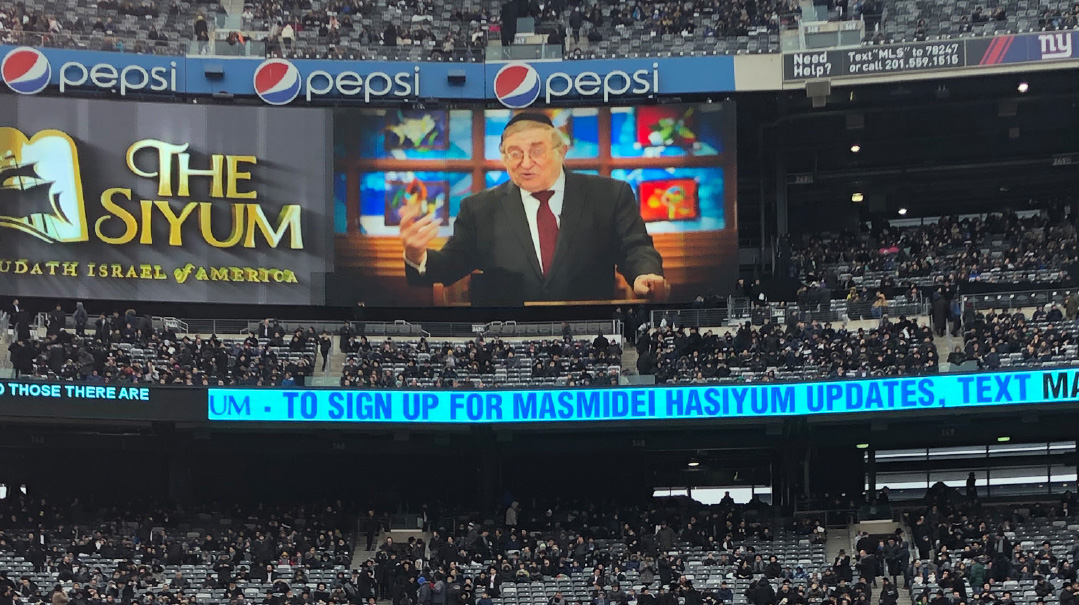

The maggid with a universal message. Addressing the crowds at a Siyum HaShas

IN 1966, a bereaved and nervous Paysach Krohn left full-time learning in order to practice milah and support his mother and siblings. Fifty-seven years and thousands of brissim have passed since then. Today, Rabbi Krohn has decided to move on. He is passing the milah profession down to his son, Reb Eliezer, and his son-in-law, Reb Ephraim Perlstein. His speaking, writing, and traveling schedule is busier than ever before, and he has decided to make that his primary focus.

Fifty-seven is gematria “zan” — Rabbi Krohn feels satiated, but there is still a gaping hole. Throughout his career as a mohel, there have been so many special moments and such special interactions. “I did a bris where Rav Chaim Kanievsky was the sandek — I was able to adjust his hands!”

Being a mohel meant stamping young Jewish infants with a mark of kedushah. It meant sharing words of inspiration with less affiliated Jews. It meant continuing in the footsteps of the father he loved so much and lost so early on.

It meant being that much closer with Avraham Avinu.

Now as he moves on, there’s a gnawing sense of emptiness; the man who feels the world’s pain admits to feeling his own as well. “Rav Yitzchak Dovid Grossman gave me so much chizuk,” says Rabbi Krohn. “He told me, ‘Until now, you’ve been inspiring families. Now, you will be inspiring Klal Yisrael.’”

Klal Yisrael is large and diverse, inspiring all of them is a tall order. But it can be done; in the world of eight, anything is possible.

But bright as the future is, taking a step back from milah after a 57-year career is hard.

And so now it’s our turn to offer words of encouragement. So here goes: Rabbi Krohn, you’ve been a mohel for 57 years, the gematria of “zan.”

But you know what else is gematria 57?

The word maggid.

Zurg zach nisht, said the man of a million words, there’s no need to worry.

The whole world is waiting for your Torah.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 980)

Oops! We could not locate your form.