Too Close to Call

We’re not the only ones in suspense after the election that isn’t over and may not be over until what Americans call “the weekend” at the earliest

W

e wish we could have declared a winner in the presidential sweepstakes by press time, as we have in the previous two elections.

Alas, to ensure that all of our readers worldwide receive their magazines before Shabbos, we were forced to close this supplement before conclusive results were available.

We’re not the only ones in suspense on Wednesday, the morning after the election that isn’t over and may not be over until what Americans call “the weekend” at the earliest.

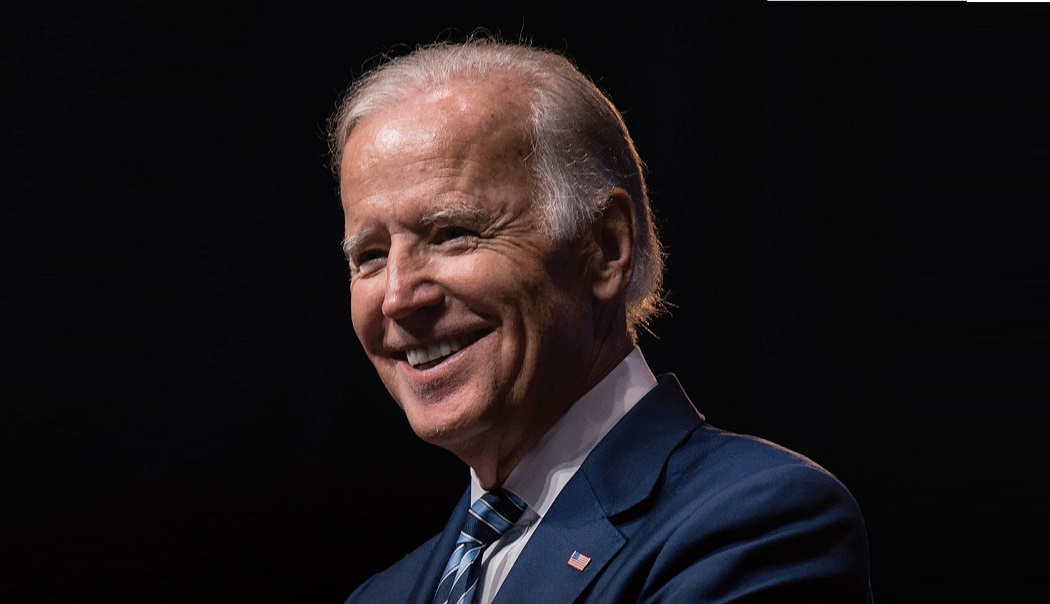

At press time, Joe Biden was leading President Trump by 2-million votes in the basically meaningless popular vote. Fox News, who works in tandem with the Associated Press, had the Democratic challenger ahead of the incumbent Trump by 238 to 213 electoral votes. CNN had Biden ahead by a smaller margin, 220 to 213.

Five major swing states that will decide the election were still outstanding, Georgia, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Michigan and Pennsylvania. While President Trump led in all of them, the races were considered too close to call based on the number of still uncounted ballots.

Biden’s path to 270 seemed a bit more challenging at press time. To get to 270, he must overcome Trump’s advantage in a minimum of two of the five battleground states where Trump went to bed with a sizable lead.

Remaining in suspense for a few extra hours or days is small potatoes compared to the challenges America’s 50 states will face in future presidential elections.

Most political analysts were correct in presuming that the Trump-Biden race would be too close to call on election night. There were still threats of lawsuits hanging in the air as both Republicans and Democrats traded charges based on a variety of technical issues that arose with absentee ballots and the fear that some were tampered with or misplaced.

These issues, and others, will have to be sorted out. Not only to determine a winner so that all Americans can be confident that the final result was honest, even if the candidate of their choice lost, but certainly for future elections for the leader of the free world.

And once again, pollsters will have to go back to the drawing board. Biden’s 2-million vote lead in the popular vote gave him a 1% edge over Trump. The Real Clear Politics average poll showed Biden on top by 7.2% the day before the election.

That’s a wide miss. In addition, the pollsters were way off the mark in several key states.

As much as pollsters say they learned the lessons from the 2016 election which they called for Hillary Clinton, they will have a lot of soul searching to do, even if Joe Biden is eventually declared the winner by a small margin.

This year nearly 100-million Americans voted before Election Day, by mail, in person, by fax (as I did in Florida, direct from Jerusalem), or by email, where permitted by law.

Much of the rush was due to health concerns over standing in long lines on Election Day during a pandemic, but it’s more than likely that early voting and voting by mail will increase in popularity as citizens demand convenience and flexibility when exercising their right to vote. To accommodate election season, states will be pressured to enact reforms in how they count ballots, and face calls to establish a uniform system to tally all votes coming at them by air, by land, and by sea.

Each state passes its own laws as to when ballots must be received or postmarked to be valid, as well as when they can begin to start counting them. Some states, such as Florida, counts the mail-in and absentee ballots as they come in. Others, such as North Carolina, could process votes in advance, but can only start tallying them when the polls opened on Election Day. Other states, such as Georgia, had to wait until the polls closed to count the early ballots. Michigan uses a bizarre hybrid system. In voting jurisdictions with more than 25,000 people, mail ballots can be processed one day before Election Day, while election officials supervising smaller jurisdictions must wait until Election Day to start counting.

Even the Supreme Court was flummoxed in interpreting the various state statutes, issuing what appeared like contradictory rulings in key battleground states. The Court allowed ballots in North Carolina to arrive up to nine days after Election Day, while limiting that to just three days in Pennsylvania; however, in Wisconsin, all ballots had to be in by Election Night.

It’s all glatt kosher, wrote Justice Neil Gorsuch, in his decision: “The Constitution provides that state legislatures — not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials — bear primary responsibility for setting election rules.”

Democratic Reform

With each state doing what’s right in its own eyes, the system becomes even more convoluted thanks to the Electoral College, which assigns more weight to the most populous states, but also spreads out the number of electors to give the smaller states an important say.

Five men, including President Trump, have won the presidency by losing the popular vote but winning in the electoral college.

This seems unfair, and a Gallup Poll released in September showed that 61% of Americans agree and favor abolishing the Electoral College.

As with everything else in America, opinions are sharply polarized. Some 89% of Democrats support doing away with it, compared to 68% of Independents and just 23% of Republicans.

It’s not so simple to do away with an American tradition that also happens to be Constitutionally mandated. The National Archives reports that over the past 200 years, more than 700 proposals have been introduced in Congress to reform or eliminate the Electoral College — without any becoming law.

The chief stumbling block to eliminating the Electoral College — as it has been almost since the dawn of the republic — is that electing the president by popular vote would steamroll smaller, more rural states with the imposition of values championed in larger coastal states. California governor Gavin Newsom, for example, has often said his state offers the model for how the whole country should be governed — even as his administration rations electricity to households, abandons forest management policies that have protected woodlands from wildfires, and spends the most per student on public education while producing test scores lower than Mississippi’s. Naturally, Nebraska residents look askance at that.

Abolishing the Electoral College would require support from two-thirds of the House and Senate, followed up with agreement from 75% of states. Another possibility floated would be to get states controlling more than 270 Electoral College votes to sign what’s called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. The compact calls on states to agree to respect the winner of the national popular vote and requires their states’ electoral votes to go to the winner, even if a particular state voted for the loser.

So far, 16 states and the District of Columbia, with a total of 196 Electoral votes, have passed the compact. Most of them are Democratic-controlled states, and this makes sense, as Democrats are still smarting from the 2016 election, when Hillary Clinton beat Trump in the popular vote, but Trump won the Electoral College; as well as 2000 when Al Gore bested George W. Bush, but thanks to several hundred invalidated votes on Florida’s punch card ballots, Bush won the Electoral College.

Even if it passed enough states, the Compact would surely be challenged in the Supreme Court. It also remains to be seen whether Democrats remain gung-ho, after the outcome of this election, and how redistricting proceeds after the 2020 Census is complete.

For example, the demographics are changing rapidly in Texas, whose 38 electoral votes make it second only to California’s 55, which is almost automatic for the Democrats. Trump’s winning margin in Texas, around 5.8% at press time was the smallest by far in decades in a state that usually grants a double-digit victory to the Republican candidate. If solid-red Texas trends blue, winning the two biggest states would provide more than one-third of the electoral votes needed to become president. Throw in blue New York with 29 votes, and much of the rest of the solid blue Northeast, with another 44 electoral votes, and any Democratic presidential candidate would become a prohibitive favorite.

The United States has always taken pride in being a bastion of political stability, with a regularly scheduled presidential elections just once every four years — unlike Israel, where the threat of elections hovers in the air almost every day, or Italy, which has had 61 governments since the end of World War II.

However, it’s no longer clear that the American system is as stable as it’s cracked up to be, and depending on the outcome of this election, we may see some major convulsions over the coming years.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 834)

Oops! We could not locate your form.