The Rising Panic

For years, they said they were panic attacks. Then I discovered the truth

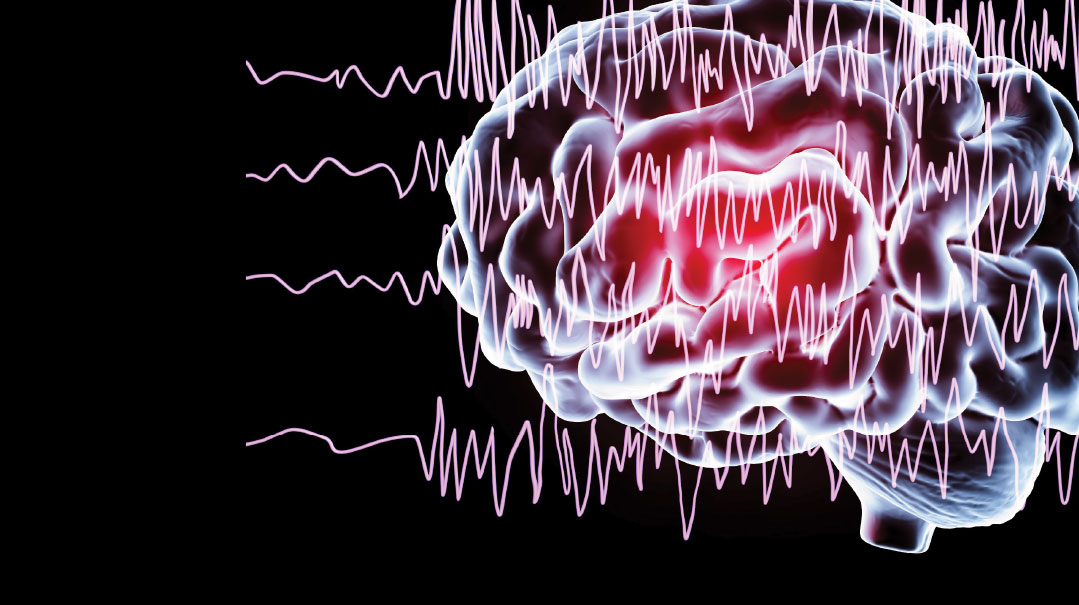

It started in tenth grade. I can easily conjure up the image of my 15-year-old self, slowly nodding off in geography class, only to be jolted awake by a buzzing sensation that traveled through my body, like a series of tiny electric shocks.

The feeling would wash over me every day, sometimes multiple times a day. It occurred so often that I basically knew when to expect it; if the bathroom became too steamy while showering, when I was drifting off in class, when I crossed at a certain street at the end of my block, as well as other places I no longer remember.

No one around me could tell when I was experiencing these weird sensations, there were no outward signs. I’d just sit or stand through it, and within 20 seconds the episode was usually over. Sometimes I’d repeat a mantra in my head — “breathe in, breathe out, breathe in, breathe out…” — until it passed.

A Panicked Diagnosis

I grew up in a happy, loving home and had a stable childhood filled with good friends and a lot of warmth. I always tended to be a bit of hypochondriac, especially when it came to health-related topics, but my anxiety never became serious or debilitating.

However, around the same time I began experiencing these electric shock feelings, I also developed a severe bout of “germiness.” I hated eating at crowded tables, with everyone breathing over my food; I found my parents’ silverware too gross to eat off of (even though my parents kept a very clean home), and I didn’t like eating anything other people had touched. I was quite thin and wasn’t gaining weight due to my aversions.

My parents became alarmed by my low weight, and they took me to a world-famous eating disorder clinic to have me evaluated. I looked at the skeletal figures roaming the beautiful grounds and thought to myself, They have it all wrong. I’m not anorexic.

Thankfully, the doctor my parents consulted agreed with my own assessment and said there was something else going on. When I explained I was experiencing the feeling of being grossed out by food as well as tingling electric shock feelings, he sent us to a psychologist, who diagnosed me with anxiety. I began working with a therapist to control my anxiety and get over my fear of germs.

Looking back, going to therapy was a pretty painless experience, as there was no deep emotional trauma to unpack or difficult family situations to work through. The appointments were relaxed, and I chatted with the therapist easily. We discussed my electric shock sensations, and she explained that the sensations I was experiencing were called panic attacks. She recommended I tell her if I felt like I was about to have one while in session, so we could work through it together.

One week, that’s what happened. I felt the strange feelings descend over me and told her I was having a panic attack. I waited patiently on the couch for it to pass — 10 seconds, 20 seconds, 30 seconds — while the therapist watched from her chair. The frightening wave passed over me, and it finished.

“Okay. It’s over.”

“That was it?” she asked, eyes wide.

“Yeah.”

“So fast?”

“Yup.” I shrugged.

I have no idea what we talked about for the rest of the session and honestly, over 15 years later, I don’t even remember the therapist’s name. But I’ll never forgot her face when she said, “That was it?” Because if there was anyone who could have realized there was something else going on, it was her.

Because panic attacks don’t last 30 seconds.

Licensed therapists should know that.

Oops! We could not locate your form.