The Missing Link

| January 16, 2024The forgotten legacy of Rav Chaim Brisker's chassidish son-in-law

Photos: Eli Cobin, Mishpacha archives, additional image sourcing by Dovi Safier

Few people know that in addition to three illustrious sons, Rav Chaim Brisker had a daughter for whom he chose a chassidishe bochur, a gaon and tzaddik named Rav Tzvi Hirsch Glickson. And even fewer know that 81 years after he and his children were murdered, his Torah lives on, salvaged by a star talmid who held onto those precious, unknown notebooks throughout years and continents

I recently embarked on an informal research project, asking local yeshivah boys, older kollel avreichim, and even respected marbitzei Torah if they could list the children of the famed Rav Chaim Brisker, considered the father of all modern- day yeshivos worldwide. As I expected, all my respondents listed Rav Chaim’s three sons: Rav Yisrael Gershon, Rav Moshe, and Rav Yitzchak Zev, the Brisker Rav. Without exception, no one mentioned Rav Chaim’s fourth child, a daughter named Sara Rasha, and her esteemed husband Rav Tzvi Hirsch Glickson. To my great surprise, even official historic websites skipped over this important detail.

Compounding the mystery is the high regard in which this gaon and tzaddik was held by all who knew him personally. One of the last eyewitnesses alive today who met Rav Tzvi Hirsch and was amazed by his tzidkus and toil in Torah is the revered posek Rav Moshe Sternbuch. In fact, Rav Sternbuch frequently mentions Rav Tzvi Hirsch in his shmuessen as a prime example of how total immersion in Torah was a reality not so long ago. Most recently, Rav Sternbuch spoke before thousands of yungeleit at a siyum held at the Mir in Yerushalayim, about the time Rav Tzvi Hirsch stayed in the Sternbuch home in England. He described his extraordinary hasmadah and tzidkus as a model for all bnei Torah to strive toward.

The impetus behind my quest to learn more about this forgotten gadol came on a recent, hectic Erev Shabbos, when I found a dear friend and neighbor standing at the doorway with a brand new sefer in his hands. Rav Yehuda Bulman, a respected rav in Neve Yaakov and a popular lecturer and mechanech in several seminaries, had brought me a sefer. In a few hurried words, he shared that his father-in-law, Reb Yitzchak Friedland, had just achieved his lifelong goal of publishing his father’s handwritten shiurim with the Torah of Rav Tzvi Hirsch Glickson Hy”d, the only son-in-law of Rav Chaim Brisker and a devoted talmid, who perished during the war together with his entire family.

This brief Erev Shabbos encounter led me on a fascinating journey in an attempt to trace the life story of this forgotten gadol. I learned of the incredible tale of the shidduch between the founder of the Lithuanian, analytical derech halimud and a very young chassidish bochur, barely 18 years old. Even more astounding was the fact that decades later, this same bochur went on to establish a litvish-style yeshivah in the heart of predominantly chassidic Warsaw between the two World Wars, attracting hundreds of students in a relatively short period.

Chapter 1: Lost in the Pages of History

The Gaon’s Revolution

The Brisker dynasty features many stellar talmidei chachamim and gedolim, but in this article we’ll focus on Rav Chaim Brisker’s only son-in-law, who somehow escaped the spotlight of history. The shidduch between Rav Tzvi Hirsch Glickson, the Polish bochur, and Sara Rasha Soloveitchik, daughter of the giant of Lithuanian scholarship, was an extremely unlikely one, underscored once we gain an understanding of the dynamics and culture that the young chassidish bochur grew up absorbing.

Two major turning points for Yiddishkeit in Lithuania (and the communities throughout eastern Europe subsequently influenced by them) are both related to the Vilna Gaon. The first relates to the style of learning adopted by Lithuanian Jewry.

While the main focus of the Rishonim is striving to understand the simple meaning of the sugya at hand, at some point, from about the 1500s onward, a different style of study known as pilpul became popular. This method emphasized comparison of several sugyos all over Shas all at once, cross referencing one to another. While the draw behind this approach was the ensuing captivating discussions and battles of minds, there were many who felt that this method of learning, which involved lengthy, convoluted explanations, led to conclusions that were contradictory to halachah. Moreover, opponents felt that the overemphasized focus on such mental gymnastics resulted in learners spending less time on the crucial basics needed to understand Torah and derive accurate halachic rulings.

Because of these reservations, the Vilna Gaon, who lived some 200 years later, subsequently introduced an entirely new method of learning, which was closer to that of the Rishonim. This method called for learning the simple pshat of the sugya thoroughly, accompanied by the major Rishonim, striving to reach a halachic conclusion from these sources. This would be achieved by covering ground and gaining proficiency in a wide range of sugyos, with a very careful reading of each and every source. The Vilna Gaon felt that focusing on discovering novel questions and searching for sharp and complex answers to them left little time to actually grasp the heart of each sugya.

Building on this dramatic change in derech halimud, an additional shift in focus was later instituted by Rav Chaim Brisker. This change involved striving to formulate the underpinnings of each sugya using abstract terminology. Once a certain sugya was precisely defined in such a manner, this terminology would be used to differentiate it from other seemingly similar ideas discussed elsewhere.

Instead of comparing sugyos all over Shas one to another, this method confined the sugya at hand as unique and not comparable to other seemingly similar ideas mentioned throughout Shas.

A second revolution, this time spearheaded by the primary talmid of the Gaon, Rav Chaim Volozhiner, focused on creating an organized and systematic framework for bochurim, both young and older. Although the title “yeshivah” unquestionably existed for many centuries before Rav Chaim’s times, it usually referred to informal gatherings, usually held in the local shul. Bochurim who were lucky to be free from assisting their families in the workforce simply gathered in the local shul and learned there with others of varying ages.

If the town was lucky to have a Talmudic genius as their local rav, these bochurim could take advantage of his eruditeness and ask him for his opinion on their respective topics of study. At times the rav would even deliver shiurim to the boys occupying his shul.

Rav Chaim Volozhiner was not happy with this state of affairs. Firstly, because there was no one supervising the learning schedule and no one in charge of arranging appropriate shiurim geared to the differing age groups and varying levels of the talmidim. And all this was aside from the fact that poor students had to take care of their personal needs by themselves. Rav Chaim witnessed a dramatic decline in serious Torah study in his days and was intent on rectifying the situation. His vision led him to found the famed Yeshivas Volozhin, which remains until this day the protype of the majority of the yeshivos worldwide.

In a short period of time, hundreds of bochurim flocked to Volozhin, enjoying the very structured environment conceived by Rav Chaim. Some scholars are of the opinion that the actual mastermind behind the idea was the Vilna Gaon himself, who implemented it through his close talmid.

Holding Firm in the East

While the above revolutionary changes took root in Lithuanian communities, in chassidic Poland the great Rebbes chose to retain the traditional method of pilpul. In fact, until the termination of organized Jewish life during World War II, the famed Poilishe derech halimud was kept very much alive.

My rosh yeshivah, Rav Hillel Zaks ztz”l, told us of a meeting that took place in a vacation resort between a great Polish Rebbe and the famed Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz, the prime disciple of Rav Chaim Brisker. The Torah discussion that ensued between these two great men left both of them perplexed, reflecting the vast gap in their respective approaches to understanding any given sugya in Shas.

The organized yeshivah system also did not take root in Poland. The great chassidic rebbes were of the opinion that what was good for Lithuania was not appropriate for Poland. However, this approach did shift over the years leading to the war, culminating in the creation of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin by Rav Meir Shapiro and a vast network of yeshivos founded and directed by the rebbes of Radomsk.

While we cannot know for sure why the chassidic rebbes objected to the litvish model of organized yeshivos, we do know their opposition was rooted in ideology. In responsa authored by the great Rebbe Chaim of Sanz, he stresses that he had heard reasoning explaining the Polish stance from the rebbes of previous generations.

Change Comes to Poland

While most of Polish Jewry held firm to the old method of pilpul, a new method did emerge in Poland itself, spearheaded by Rav Avraham Borenstein, known as the Rebbe of Sochatchov or simply as the Avnei Nezer, after his sefer by that name. The Avnei Nezer was the prime talmid and son-in-law of the Rebbe of Kotzk, renowned for his adherence to the middah of emes and a demanding approach as a rebbe to his chassidim.

Similar to the Lithuanian objection to pilpul, the Avnei Nezer preferred a careful study of the words of the Rishonim and clarifying the pshat of the sugya at hand. Unsurprisingly, his sefer Eglei Tal, an analytical study on 11 of the 39 Melachos Shabbos, was enthusiastically received and learned in Lithuanian-style yeshivos worldwide.

The Avnei Nezer established a yeshivah in Sochatchov, where he taught his talmidim according to his unique style of learning. (Incidentally, one of the great geonim to immigrate to the United States during World War I was Rav Michoel Forshlager of Baltimore, a prime talmid of the Avnei Nezer in Sochatchov.)

Another close talmid of the Avnei Nezer was a wealthy businessman and Torah scholar by the name of Rabbi Avraham Yaakov Glickson who resided in Warsaw. Reb Avraham Yaakov merited to have a prodigious son named Tzvi Hirsch, and invested much time tutoring him in Torah, in addition to hiring private melamdim to teach him. Interestingly, Reb Avraham Yaakov was of the opinion that one must follow the dictum of the Mishnah stating one must be fluent in the Six Sedorim of Mishnah by the age of 15, and did not teach his son Gemara until that age (as heard from Rav Herschel Schachter, as heard from Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik).

Possessing a unique intellect, young Tzvi Hirsch mastered the entire Mishnah and knew it by heart by the age of 12. In addition, he mastered all the references to sugyas in Shas mentioned by the commentaries of the Mishnah but did not study the Gemara inside until later on in life. Rav Moshe Sternbuch testified recently that when Rav Tzvi Hirsch visited England to fundraise for his yeshivah, he heard him mumbling Mishnayos by heart, in order not to waste a minute without Torah study.

Reb Avraham Yaakov also made sure that his young son would absorb the derech halimud of his own rebbi the Avnei Nezer by arranging for his rebbi to talk with him in learning.

Chapter 2: Surprising Choice

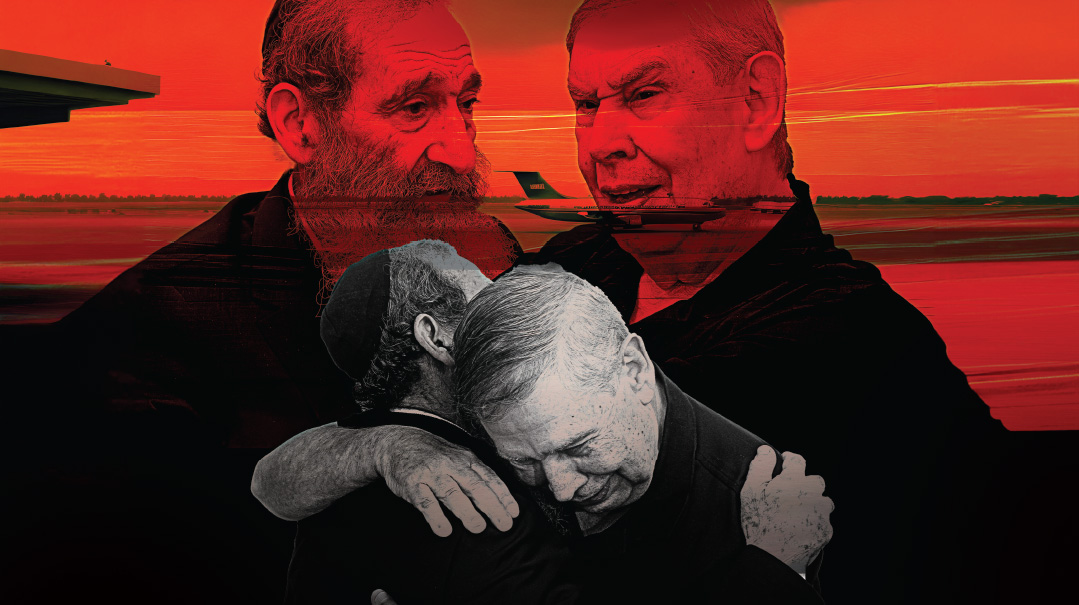

When Rav Chaim decided to give his daughter’s hand in marriage to a chassidish bochur who hadn’t learned Shas inside yet until very recently, the news made waves.

When Rav Chaim visited Warsaw, all the city’s great Talmudic minds came out to greet him and talk with him in learning. Two young budding Torah scholars named Tzvi Hirsch Glickson and Nosson Spiegelglass (later one of the great geonim of prewar Poland) joined the crowds hoping to meet with Rav Chaim.

Rav Chaim immediately grasped the sheer genius of Tzvi Hirsch and promptly offered him his only daughter, Sara Rasha, as a shidduch. Tzvi Hirsch consulted with the Rebbe of Gur, of whom he had become a chassid, and the rebbe encouraged Tzvi Hirsch to grab the opportunity. And so at the young age of 17 years old, Tzvi Hirsch Glickson from Warsaw became the son-in-law of the gaon of the yeshivah world.

News of the unlikely match quickly made rounds, and people close to Rav Chaim asked why this great lamdan took a chasiddish bochur illiterate in Shas as a future son-in-law. Rav Chaim responded that he preferred to train a young bochur himself in the study of Shas rather than to choose one who had learned on his own and try to change his “crooked” way of thinking at an older age.

Brisker family tradition has it that there was an encounter between Rav Chaim Brisker and Reb Avraham Yaakov way before they became mechutanim, in a chance meeting in Lodz. Rav Chaim had come to Lodz and was seeking out a minyan to hear Krias HaTorah. Upon finding that some of the ten Jews assembled had already heard the Torah reading, Rav Chaim ruled that the kriah could not take place without a complete minyan of men who hadn’t heard it yet. One of the assembled had enough courage to disagree with Rav Chaim on the matter, proving his point from one of the Rishonim. While Rav Chaim was not convinced, this encounter marked the first meeting between the future mechutanim.

Under Rav Chaim’s Tutelage

After the chasunah, Rav Chaim’s newlywed young son-in-law became a full-fledged talmid of his, toiling in Torah together with his youngest son, Rav Yitzchak Zev. At a certain point, Rav Chaim entrusted them with summarizing his chiddushei Torah in writing. At one such session, after which Rav Chaim orally delivered a chiddush in their presence, the two sat down again to clarify the sugya between themselves but came up with several questions.

When they entered his room hoping to ask their questions, Rav Chaim looked up and said, “I know why you came to me. Since you were bothered by this and this problem, well, the answer is such and such, and you can rely on me that when I say you can write up the chiddush, I know what I am talking about.” And all this was without them saying one word.

These wonderful, fruitful years were interrupted by World War I, when Rav Chaim’s family, including Rav Tzvi Hirsch, were forced to flee to Minsk. In Minsk, the Russian government decided to draft previously exempt personnel into the war effort. Rav Chaim was faced with the dilemma whether or not to forge documents for his son and son-in-law attesting that they were officiating rabbis which might have assisted them in avoiding the draft. Ultimately, he chose not to, but sources debate the reasoning behind his decision. Some believe Rav Chaim feared that these false exemptions would prevent authentic officiating rabbis from receiving their rightfully deserved exemptions. Others are of the opinion that Rav Chaim did not trust the Russians and was afraid that once the young men’s information would be in their hands, they would draft them nevertheless, now that they could easily be tracked down. In any event, Rav Chaim somehow managed to prevent them from being drafted without forging any documents.

Rav Chaim passed away toward the end of the war, while it was still impossible to reach Brisk because of security concerns. His levayah and kevurah took place in Warsaw, where he was buried alongside his grandfather-in-law, the Netziv of Volozhin. Rav Tzvi Hirsch and Rav Yitzchak Zev decided to remain in Warsaw, where Rav Tzvi Hirsch knew the great lamdanim of Warsaw, such as his old friend Rav Nosson Speigelglass and Rav Menachem Ziemba Hy”d.

Brisk Meets Warsaw

At the same time, there were others stuck in Warsaw, including a leading Yerushalmi talmid chacham named Rav Yeshaya Winograd, initially sent by Yeshivas Toras Chaim in Yerushalayim as a fundraiser to Lithuania. During this visit, he stopped over in Brisk and participated in a shiur delivered by Rav Chaim.

Rav Winograd was bothered by Rav Chaim’s line of thought, but hesitated to interrupt the shiur with a question. After much deliberation, Rav Winograd just said, “But in Chullin…” before the crowd hurriedly shushed him in deference to Rav Chaim. Nevertheless, Rav Chaim heard and asked Rav Winograd to continue with his question.

“It seems to me that the Rav’s chiddush is not aligned with a sugya in Chullin,” Rav Winograd said. Rav Chaim immediately grasped what he had in mind and roared, “Not enough that it is not aligned with my chiddush, it completely contradicts my chiddush!” And he stopped the shiur right there. (As heard from Rav Moshe Mordechai Schulzinger.)

This encounter with Rav Chaim made a deep impression on Rav Winograd, who decided to delay his departure from Brisk so he could absorb Rav Chaim’s unique derech halimud. Eventually, the war forced him to flee to Warsaw, where he learned of Rav Chaim’s passing.

Fueled by his fierce love for Rav Chaim and his methodology, Rav Winograd conceived the idea of creating a yeshivah named after Rav Chaim that would follow his unique style, a previously unimaginable feat. But considering the fact that Rav Chaim’s son, Rav Yitzchak Zev, and his son-in-law, the chassidic Rav Tzvi Hirsch, had decided to stay in Warsaw, Rav Winograd had hope that under their leadership, the yeshivah would take off, even in chassidic Poland.

A local philanthropist named Mrs. Sima Brodie, the widow of Rabbi Yaakov Broide (the donor of the Batei Broide neighborhood in Yerushalayim), graciously donated the yeshivah campus on Genche Street 45, alongside another complex allocated to an elementary school and yeshivah ketanah under the auspices of the yeshivah.

The yeshivah, named Toras Chaim after Rav Chaim Brisker, saw immediate success, with an enrollment of hundreds in its very first years of existence. While Rav Yitzchak Zev returned to his hometown of Brisk to assume his father’s position as rav soon after the yeshivah’s opening, Rav Tzvi Hirsh remained in Warsaw and Toras Chaim flourished.

Not only young boys born into Lithuanian families were drawn to the yeshivah but full-fledged chassidim as well, which was remarkable considering the totally different style of learning between these two sectors of frum Jewry.

One of these talmidim, a Gerrer chassid by the name of Shlomo Freidland, studied in Toras Chaim for four years and recorded his rebbi’s shiurim in a neatly organized notebook. It would ultimately be the only surviving remnant of Rav Tzvi Hirsch’s Torah.

Blending Two Torah Kingdoms

At a later point, Rav Tzvi Hirsch’s own son-in-law Rav (Avraham) Meir Finkel Hy”d, son of Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, the rosh yeshivah of Mir in Europe and Eretz Yisrael, joined the yeshivah’s staff, serving as a rebbi and assisting his father-in-law in running the yeshivah.

A description authored by Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, the Seridei Aish, recounting the months he spent in the Warsaw ghetto, offers vivid testimony of Rav Meir’s genius. Rav Weinberg recounts the great mesirus nefesh of the talmidei chachamim who toiled in Torah even while in the ghetto, and describes plans to print a compilation chiddushim on one specific halachah relating the prohibition of chometz on Pesach. He singles out the article submitted by Rav Meir Hy”d as one that “blew people away” due to its sheer brilliance.

Rav Meir was murdered by the Nazis, and his father, Rav Eliezer Yehuda, abstained from eating meat until the end of his life.

Family lore recounts an interesting anecdote concerning the wedding of Rav Meir and Tzirel, the daughter of Rav Tzvi Hirsch. The chasunah took place in Drozgenik, a small resort town not too far from Grodno that had a local rav. Although all the gedolei hador were present at the wedding of Rav Chaim’s granddaughter with the grandson of the Alter of Slobodka (Rav Eliezer Yehuda’s father), none of them served as mesader kiddushin, in deference to Rav Chaim’s opinion that the mara d’asra (the local rav) deserves this kibbud.

Until the Bitter End

The yeshivah was in existence for 20 years until the outbreak of World War II. There are two conflicting accounts describing Rav Tzvi Hirsch’s last days. The first, by his brother-in-law Mordechai Driehoren, claims that he passed away in the Warsaw ghetto in 1942, while another account, submitted to Yad Vashem in 1957 by Adina Pomerantz of Bnei Brak (relation not specified) testifies that he perished in Treblinka in that same year.

Rav Moshe Sternbuch recounts a discussion he had with the Seridei Aish (who was with Rav Tzvi Hirsch in the Warsaw ghetto), whose account concurs with the testimony submitted to Yad Vashem by Adina Pomerantz.

Rav Weinberg told Rav Sternbuch that although Rav Tzvi Hirsch and his entire family were suffering from starvation, he was constantly learning with his sons with great hasmadah, oblivious to his surroundings. He actually authored a sefer under these harsh conditions dealing with the complex issue of terumas hadeshen (the avodah in the Beis Hamikdash involving removing the ashes of the previous day’s korbanos) and other complex halachic topics.

He also married off a son in the ghetto, who was murdered shortly afterward, along with his kallah and his mother, Rav Tzvi Hirsh’s wife. In a shiur delivered by Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, he described the horrific death of Rav Tzvi Hirsch’s son, Rav Yeshaya, and his newlywed kallah at the hands of the nazi beasts. Rav Tzvi Hirsh himself was then deported to Treblinka and murdered, with words of Torah constantly on his lips until the end.

All of his children, among them young talmidei chachamim, were murdered during the war (aside from one who passed away before the war), as well as his son-in-law Rav Meir Finkel, who died from complications caused by the malnutrition common in the ghetto.

Chapter 3: Preserved for Posterity

From Warsaw of the 1930s to Yerushalayim of 2023…

My neighbor Rabbi Yehuda Bulman, whose Erev Shabbos visit swept me on a journey into the past, introduces me to his father-in-law, Yitzchak Friedland. Sitting comfortably in his Jerusalem home, I merit to hear the third part of the tale. He tells me about his father, Rabbi Shlomo Meir Friedland, a loyal talmid of Rav Tzvi Hirsch who recorded some of his shiurim for posterity.

Rav Shlomo Meir grew up in a small village near Warsaw. His father was a Gerrer chassid, and their large family enjoyed prosperity thanks to the factory they owned in Warsaw. However, World War I signaled a change to the family’s fortunes. A German war plane bomb destroyed the factory completely, leaving the family penniless, with many mouths to feed.

The Friedlands were forced to send out their older children to work so they could contribute to the family’s income; however, Shlomo Meir, the youngest son, was deemed too young. At first, he attended cheder in his hometown but subsequently, as his thirst for Torah learning became apparent, his parents decided to enroll him in Yeshivah Toras Chaim in Warsaw. Shlomo Meir excelled in his studies (eventually receiving semichah there), and drank in the clarity and depth of Rav Tzvi Hirsch’s shiurim, which he was careful to record in extremely clear handwriting.

As a staunch Gerrer chassid as well, Shlomo Meir figured out a way to quench his thirst for chassidus in a novel manner. Until this day, the highlight of the year for Gerrer chassidim is Shavous, when thousands of chassidim gather to spend Yom Tov with the Rebbe, at that time, the Imrei Emes ztz”l (who himself was niftar on Shavuos of 1948). And while Shlomo Meir did not have the funds to cover the cost of traveling from Warsaw to Gur, he was undaunted.

Every day he received a kopeck from his mother to cover the cost of the bus ride from his home to Toras Chaim. Shlomo Meir opted to go and return from yeshivah by foot, an hour-long walk each way, and save the money for Shavous in Gur. He later recounted that the Shavous in Gur in the presence of the Rebbe was the highlight of his life.

Move to the Fruited Plains

While Shlomo Meir was flourishing in Toras Chaim, his time there came to a halt when he was recruited to join Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan (RIETS) in New York. Rabbi Dr. Dov Revel, RIETS’s founder, was looking for ways to enhance the Talmud study in his yeshivah, striving to emulate the level that existed in Europe. To this end, Rabbi Revel dispatched his right-hand man, Rabbi Dr. Shmuel Sar, a musmach of Telz, to Warsaw to search for yeshivah boys of high caliber. Rabbi Sar’s mission was to persuade them to come to RIETS, where they would simply learn in the beis medrash, without learning English or any secular studies.

Knowing a lamdan when he saw one, in 1935 Rabbi Sar recruited 21-year-old Shlomo Meir, who was still single, to join RIETS. But Rabbi Revel’s plans did not materialize entirely as he had hoped: All the European bochurim who joined the yeshivah at Rabbi Sar’s behest did learn English and eventually became rabbis in the States, Shlomo Meir among them.

He stayed in RIETS for five years, where he also learned English and received a second semichah (aside from the first he received in Toras Chaim), enabling him to search for a rabbinic position in the United States. Rabbi Friedland was offered a position in the small town of Athol, Massachusetts. He stayed in Athol for two years until 1942, when he decided to move back to New York and settled in Forest Hills. There he founded Congregation Ahavath Sholom.

Years later, when some of the members of the congregation wished to tamper with the Orthodox character of the shul, Rabbi Friedland protested that the suggested changes ran contrary to the shul’s charter. Not willing to back down, one member asked how Rabbi Friedland knew that.

“Because I wrote the charter,” he responded.

Enduring Bond

As a respected rav in New York, Rabbi Friedland used his connections to help Rav Tzvi Hirsch fundraise for the yeshivah of his youth. In fact, Reb Yitzchak shows me a letter written to Rav Shlomo Meir and signed by Rav Tzvi Hirsch.

(On the subject of Rav Tzvi Hirsch’s fundraising efforts, a different heartwarming anecdote centers around Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz, the prime talmid of Rav Chaim Brisker. Rav Yitzchok Isaac Tendler, a long time rebbi in RJJ and a close talmid of Rav Baruch Ber, was living in New York when his rebbi came to collect funds for his own Yeshiva Knesses Beis Yitzchak in Kamenitz. Eager to assist, Rav Yitzchok Isaac organized an evening to help raise funds for the yeshivah. At this same time, Rav Tzvi Hirsch was also fundraising in America for Toras Chaim.

At the event, Rav Boruch Ber gave a fiery speech culminating in the request to donate to… Toras Chaim. The speech made a tremendous impression and Toras Chaim received a lot of money that evening. Distraught, Rav Yitzchok Isaac asked Rav Boruch Ber why he had sabotaged the fundraising effort for Kamenitz. Rav Borch Ber replied, “The Rebbe [Reb Chaim Brisker] did so much for Klal Yisrael. Does not he deserve that we pay him back a little?”

As news of the atrocities committed against Jews all over eastern Europe reached American soil, Rabbi Friedland worked tirelessly to obtain visas for his family. He eventually managed to bring over his parents, brothers, and sisters to America. Not content with this achievement, he repeatedly tried to obtain visas for cousins as well. To his great sorrow he did not succeed. In a letter written to him by one his relatives, they stressed that if the visas would not arrive in the next few days there would be no hope left for them. This was the last correspondence he had with these cousins.

In December 1945, at the age of 32, Rav Shlomo Meir married Devorah Rechil Skolnick. Her father, Reb Dovid Aryeh Halevi Skolnick, was from Lemberg, or Lviv, now Ukraine. Rebbetzin Friedland was a loyal wife, mother, and supporter of her husband’s endeavors until his untimely passing.

Rabbi Friedland remained a staunch Gerrer chassid throughout his life, even after adopting a clean-shaven American appearance. He remained loyal to the upkeep of Gerrer mosdos worldwide, and made a point of attending each and every dinner, parlor meeting, and Melaveh Malkah dedicated to the cause.

His last appearance was when he joined a group of chassidim who came to greet the Lev Simchah (before he became Rebbe of Gur) at the airport. During this event, he suffered a serious injury to his knee. He had been suffering from a heart condition for several years, and this injury complicated his health situation further. In 1966, Rav Shlomo Friedland passed away at the relatively young age of 51.

His Torah Will Live On

After his death, his children found his prized possession: a neat and orderly notebook containing the shiurim he had heard years earlier from Rav Tzvi Hirsch, whom he had revered and loved his entire life. The notebook doesn’t display the rushed writing one would expect of someone summarizing a live shiur. Apparently, Rabbi Friedland first summarized the shiurim while Rav Tzvi Hirsch was speaking, then copied and edited them once again later on.

The cherished notebook, now in the hands of Reb Yitzchak, propelled him with a sense of mission to publish the last remnant in this world of his father’s rebbi’s Torah. While several chiddushim of Rav Tzvi Hirsch were recorded by Rav Boruch Ber in his Birkas Shmuel and are learned in yeshivos worldwide until today, there was no organized sefer of Rav Tzvi Hirsch’s Torah, nor are there any surviving descendants of his family.

Reb Yitzchak carefully guarded this notebook for years, attempting from time to time to find someone who had the expertise to work on the project and would appreciate its magnitude. But the breakthrough came about only after Reb Yitzchak fulfilled another lifelong dream and settled in Eretz Yisrael.

Reb Yitzchak’s dream to publish his father’s rebbi’s shiurim never left his mind, and he began once again to search for the right man for the job. Someone suggested Rav Simcha Pachtman, a local talmid chacham in his own right, as a suitable candidate. Rav Pachtman immediately grasped the true value of the shiurim and set out to transcribe them for print.

A second stage, which would significantly enhance the future sefer, was to find Torah scholars fluent in the Torah of Brisk who would compare the content of the sefer with other existing writings of Rav Chaim Brisker. These included his own writing in Chiddushei Rabbeinu Chaim Halevi and the notes of his live shiurim compiled in the sefer known in the yeshivah world as Rav Chaim’s Stencils.

In addition, Reb Simcha invested much effort in compiling a fascinating preface which focuses on the little-known details of Rav Tzvi Hirsch’s life. The only preexisting source describing Yeshivah Toras Chaim was a short chapter in a historical book titled Ishim v’Kehilos authored by Rabbi Moshe Tzinovitz who knew Rav Tzvi Hirsch personally. The current sketch in the preface to the newly released sefer Shiurei Toras Chaim is the only existing biography of Rav Tzvi Hirsch and his family, coupled with a description of his unique yeshivah in Warsaw.

Several weeks ago, the Yefe Nof publishing house produced the sefer, which was received with acclaim by Torah scholars and yeshivah students. Eighty-one years after he and his family were murdered in Treblinka, this great gaon and tzaddik’s legacy lives on due to the efforts of a loyal talmid and his devoted son. —

Shiurei Toras Chaim

The recently released Shiurei Toras Chaim focuses on the shiurim delivered by Rav Tzvi Hirsch Glickson spanning the years during which Rabbi Friedland attended his yeshivah in Warsaw. One of the trademark symbols of a litvish style yeshivah is the cycle, spanning several years, during which the yeshivah strives to cover the “yeshivishe masechtos” in depth.

Practically speaking, this means that instead of investing the years in yeshivah to finish Shas, the yeshivah chooses to focus on several select tractates and learn them with a focus on understanding these sugyos in depth and defining the laws mentioning in them in precise abstract terms (primarily according to terminology laid down by Reb Chaim Brisker).

The tractates chosen are usually from the sedorim of Nashim and Nezikin.

In sefer Shiurei Toras Chaim, Rabbi Friedland recorded shiurim delivered by Rav Tzvi Hirsch on the following masechtos of Seder Nashim: Gittin (laws of divorce) and Kiddushin (laws of marriage). From the masechtos of Seder Nezikin he recorded shiurim on Bava Kamma, Bava Metzia, and Bava Basra (all dealing with monetary halachah). A third part is dedicated to general topics discussed in depth in the yeshivah world.

Aside from the shiurim themselves, the Torah scholars engaged by Rav Simcha Pachtman provided cross references for the chiddushim in the name of Rav Chaim Brisker as heard from Rav Tzvi Hirsch, comparing them to similar chiddushim that appear in other sources quoting Rav Chaim’s chiddushim. These are of particular importance since the precise definition of these abstract terms are the fundamental aspect of the Brisker derech. Other footnotes deal with providing sources of terms mentioned in Rav Tzvi Hirsch’s shiur, clarifications, and cross references to works of Rishonim on these topics.

A fascinating addition to the sefer is an exhaustive preface dedicated to the life of Rav Tzvi Hirsch, tracing his marriage to Sara Rasha, the daughter of Rav Chaim Soloveitchik; his appointment as rosh yeshivah of Toras Chaim in Warsaw, where his duties included the requisite fundraising; and his death and the death of all of his children before and during the war.

Lithuanian Aristocracy

The Brisker dynasty began with the Beis HaLevi, the first Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik (many descendants would later carry this name). Rav Yosef Dov himself was a descendant to many great Torah scholars but was the first Soloveitchik to carry the title “Rav of Brisk.”

Rav Yosef Dov, a grandson of Rav Chaim of Volozhin, was appointed co-rosh yeshivah of Volozhin alongside the Netziv, a son-in-law of Rav Yitzchak of Volozhin (and son of Rav Chaim). He later left Volozhin to accept the position of Rav of Slutzk. Many Volozhin talmidim followed him there, in addition to new ones who came to hear his shiurim. After leaving Slutzk due to disagreements with askanim, he spent a short period in Warsaw, before moving to Brisk where to assume the rabbanus, succeeding Rav Yehoshua Leib Diskin who was forced to flee to Eretz Yisrael.

Although the Beis HaLevi had many children from three marriages, his son from his second marriage, Rav Chaim, stands out as the founder of the current day yeshivah method of learning, the “Brisker Derech.”

Another son, Rav Simcha, (from his third wife), was rav of Mohilov and taught in the yeshivah of Rav Pesach Pruskin. Rav Simcha reached the shores of America where he taught a small group of select talmidim in New York and eventually was appointed the rav of Anshei Brisk in the city.

A son of Rav Simcha was Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik of Spring Valley, father of Rav Yitzchak Soloveitchik of Yerushalayim and Rav Simcha.

Rav Chaim Soloveitchick assumed both of his father’s positions, first as co-rosh yeshivah of Volozhin alongside the Netziv, where he introduced his unique analytical methodology, then as rav of Brisk. (He was actually a grandson-in-law of the Netziv, as he married the daughter of Rav Refael Shapiro, son-in-law of the Netziv.)

When the Russian authorities closed down the yeshivah in Volozhin, he became rav of Brisk, where he saw his main mission as Rav to be involved in day-to-day activities of chesed, caring for the welfare of the city’s inhabitants. Halachic rulings were left to the dayan, Rav Simcha Zelig Riger Hy”d.

Rav Chaim himself had three sons. The oldest, Rav Yisrael Gershon, was a great Torah scholar and tzaddik who assisted his grandfather the Beis HaLevi during his lifetime. An extant photo shows an elderly Rav Yisrael Gershon with the talmidim of the yeshivah ketanah of Brisk, a possible indication that he was a marbitz Torah in this yeshivah. Rav Yisrael Gershon was killed during the war and was survived by his son Rav Moshe of Switzerland, recognized as the foremost gadol in Europe for many years until passing in 1995. His son is Rav Boruch, the rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Toras Zeev (formerly in Yerushalayim, currently in Beit Shemesh).

Rav Chaim’s second son was Rav Moshe, who was appointed first as rav of Raseiniai and then of Chaslovitch. Later on, he served as rosh yeshivah in Tachkemoni in Warsaw and finally as rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan in New York. His sons were Rav Yosef Dov of Boston who succeeded him as rosh yeshivah in RIETS; Rav Aharon, the rosh yeshivah of Brisk in Chicago (aside from earlier positions held in Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin and Skokie); and Dr. Shmuel, a chemist. Rav Moshe’s two daughters were Mrs. Shulamis Meiselman (mother of Rav Moshe Meiselman, Rosh Yeshivas Toras Moshe in Yerushalayim); and Dr. Anne Gerber.

The youngest son of Rav Chaim was Rav Yitzchak Ze’ev, known as Rav Velvel, or the Brisker Rav, who assumed his father’s position as rav of Brisk and taught an elite group of hand-selected talmidim from the major yeshivos of Europe at his home in Brisk. Although not a formal yeshivah setting, many of the subsequent gedolim of the next generation considered themselves talmidim of the Brisker Rav because of these sessions. These informal shiurim continued upon the Brisker Rav’s arrival in Eretz Yisrael during the war, this time catering to the elite talmidim of the existing yeshivos in Eretz Yisrael.

His sons were Rav Yosef Dov of Yerushalayim, who opened the first formal yeshivah of Brisk in Yerushalayim (now headed by his son Rav Avraham Yehoshua); Rav Chaim, known in the yeshivah world for his sharp and lomdishe wit; Rav Meshulam Dovid, who eventually founded an additional Yeshivas Brisk in Yerushalayim; Rav Rephael, who dedicated his life to assisting his father and was involved in early battles for upholding Yiddishkeit in the newly formed State of Israel; and Rav Meir who taught select talmidim in a small yeshivah setting.

The Rav’s two sons-in-laws were Rav Michel Feinstein, Rosh Yeshivas Beis Yehuda in Tel Aviv; and ybl”ch Rav Yaakov Schiff, currently based in Yerushalayim. Three other children were murdered during the war together with the Rav’s Rebbetzin Hy”d.

The fourth sibling was a daughter of Rav Chaim named Sara Rasha, who married Rav Tzvi Hirsh Glickson. Hashem yikom damam.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 995)

Oops! We could not locate your form.