The Fine Print

Whether it’s handwritten medieval manuscripts or kisvei yad from gedolei Yisrael, Israel Mizrahi's bookstore is a virtual paradise

Photos: Itzik Roytman, Personal archives

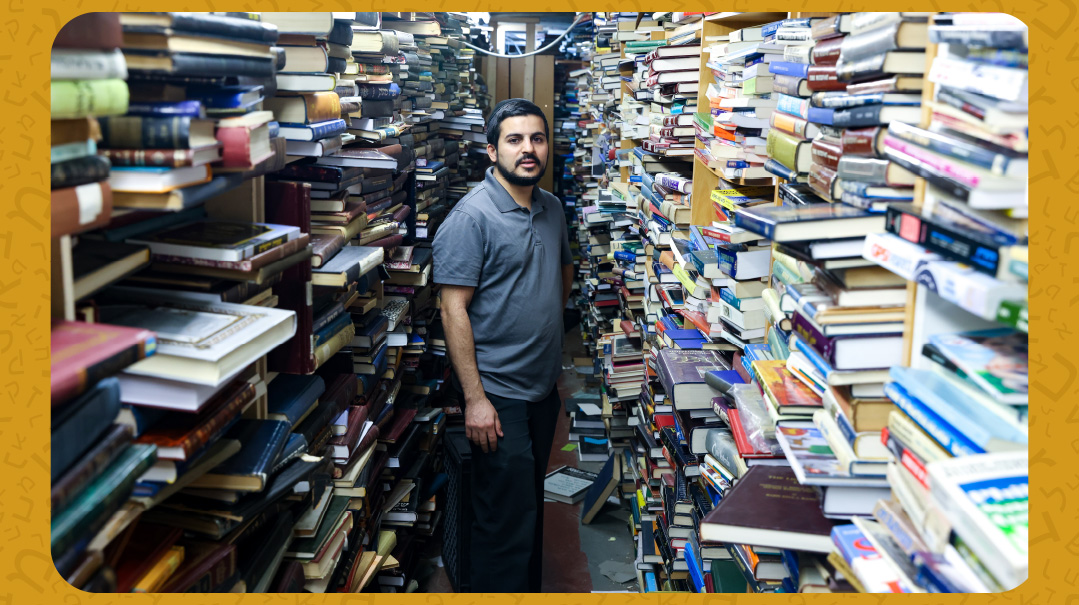

The white decal on the door of 3114 Quentin Road in the Marine Park section of Brooklyn, New York, reads “Lifschitz Realty.” Should you want visual confirmation of that fact, you’re out of luck; plastered to the locked glass door is an Israeli flag so sun-bleached, its blue stripes are pink, and the view through the full-length glass windows alongside it is obscured by tall, almost-empty bookcases.

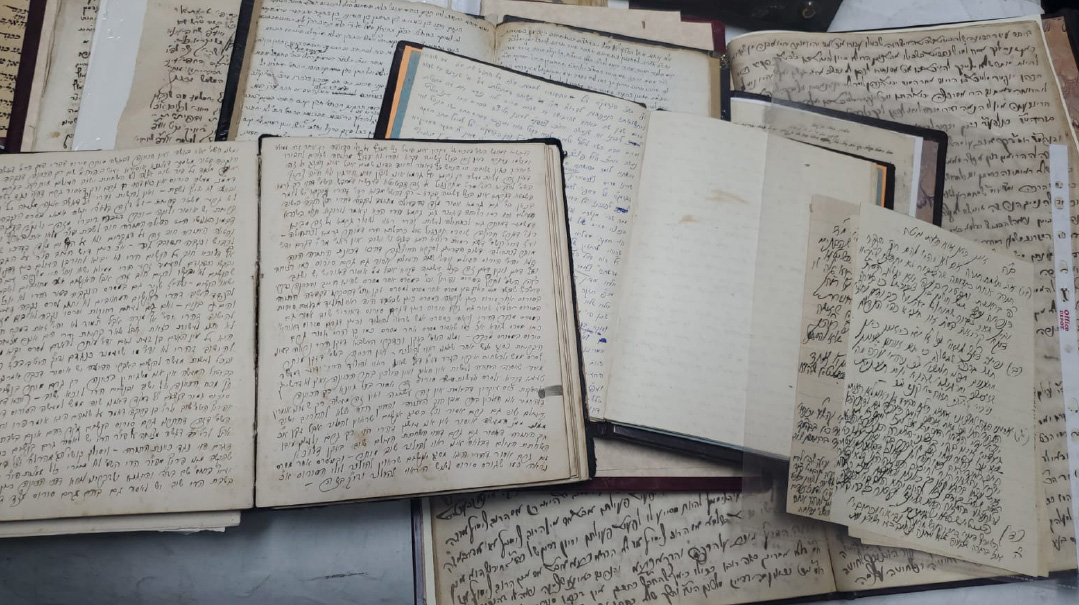

If you ring the bell and are let in, the security measures up front make a little more sense as you find yourself standing in a modern-day Cairo Geniza. Its proper name is Mizrahi Bookstore, and to be fair, if you take another look at the front door, you might notice a small paper affixed to it with Scotch tape making that claim.

This is no place for the claustrophobe: The space is a warren of books, many on shelves but thousands more in tall stacks sprouting from the floor. There is barely enough aisle width to put one foot in front of the other as you try to navigate your way through.

Proprietor Israel Mizrahi is quite familiar with the shocked look on your face.

“Don’t worry, the chaos in here is controlled,” he greets you.

If you’re surefooted enough to make it to the back, you will be treated to the Kodesh Hakodoshim: Mizrahi’s office, home to the rarest and most valuable books, manuscripts, and documents in his collection. It is a literal sea of bound publications, leaving little room to stand. Don’t bother bringing your coffee cup with you; there will be nowhere to put it down.

While technically a bookstore, the moniker is just the humblest hint of Mizrahi’s enterprise. Handwritten medieval manuscripts, first-edition seforim from the earliest days of printing, correspondence, chiddushim, and kisvei yad of gedolei Yisrael spanning hundreds of years and every corner of the Jewish globe are bought and sold here daily.

“I’m not the bookstore for your kids’ school seforim lists,” he says with a small smile.

The 36-year-old father of five has lived all his life within the same few blocks in Flatbush. His father, Shlomo, immigrated to the US from Syria in the 1960s; his mother, Batsheva, came from Morocco in the 80s. At home, Hebrew was the language of choice.

“I’ve always been a huge reader,” Mizrahi says. “I’ve been reading books in Hebrew since my earliest childhood, which turned out to be a huge advantage in my work.”

By the time he married his Jerusalem-born wife Rivka Bensaadon at age 20, Mizrahi had amassed quite a collection of books. He was in kollel at the time, and would spend about an hour a day selling his used books online.

“Then a friend told me his grandfather’s personal library was for sale, and I bought the entire lot to sell,” he remembers. “One library led to another, and of course books require space, so here we are — even if I wanted to retire today, I truly don’t see a way out,” he says in all seriousness.

That’s it. For all the history contained within its walls, the history of the store itself is rather sparse.

But the diehards don’t mind. They come for the resources, the camaraderie, the company of like-minded people — and the proprietor.

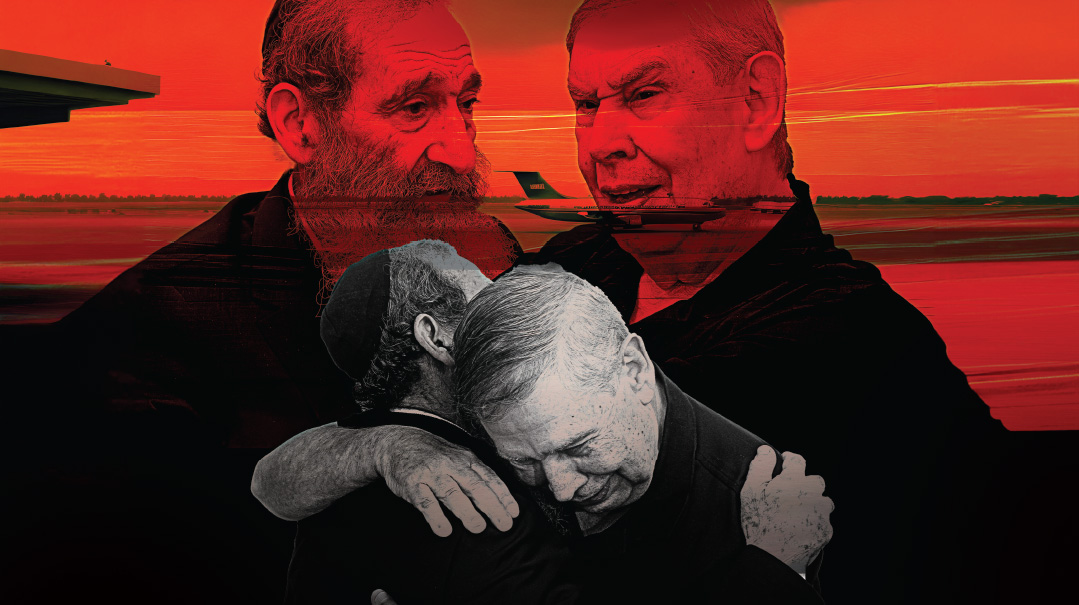

Mizrahi Bookstore on Quentin Road is a modern-day Cairo Genizah

Mizrahi’s steady customers tend to drop in once or twice a week to see what’s new and to soak up the Mizrahi Experience: the opportunity to cross the boundaries of time and space. The store serves as a coffeehouse of sorts, sans coffee, for a community of booklovers who are intensely curious and passionate about their areas of interest. The average visit, says Mizrahi, is three hours — once inside, time really does disintegrate.

For researchers, Mizrahi Bookstore is the Promised Land. An Artscroll editor from Monsey has battled New York City traffic almost every Sunday for the past decade in order to sift, compile, compare, interpret, and clarify material.

One intrepid rosh kollel from Israel used Mizrahi’s manuscripts to do something few over the past hundred years have been brave enough to try.

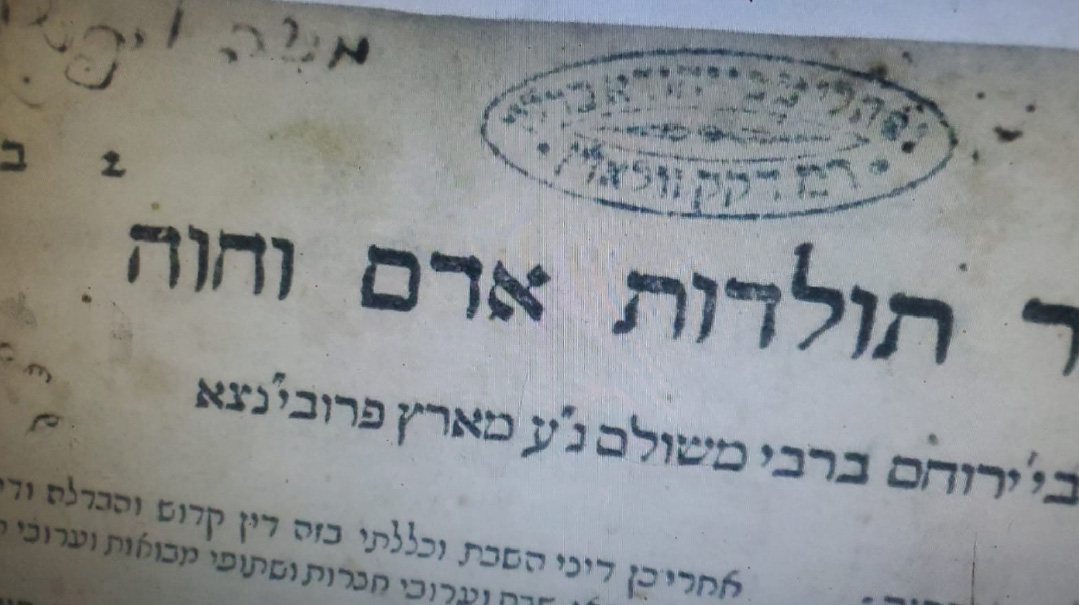

“The printed works of the Rishon Rabbeinu Yerucham are, in the words of the Acharonim, hard to use because they’re ‘meshubash — unclear’. The print job, done in the 1500s, was a sloppy one,” Mizrahi explains.

In the following centuries, several people attempted to write clarifying commentary on the text, but unfortunately many of them died young. Thus developed a myth that anyone who tampers with the words of Rabbeinu Yerucham risks an early death. In the 1700s, the Chida wrote that there is absolutely no basis for this myth, but this inadvertently spread the legend much further.

“I believe since the Chida’s times, no one has touched the words of Rabbeinu Yerucham,” Mizrahi says. Now with haskamos from Rav Ovadia Yosef and Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, this rosh kollel took on the yearslong project, specifying in his introduction that he’s just clarifying the actual text and not adding commentary — just in case. Mizrahi lent him the Netziv’s personal copy of Rabbeinu Yerucham with the Netziv’s own notes written in the margins, which were extremely helpful to the rosh kollel. He’s since published a clear edition of Rabbeinu Yerucham, the first in about 500 years.

A young woman writing her PhD on a subject pertaining to Russia had been searching for three years for a specific issue of a Russian Jewish scholarly journal. She somehow found Mizrahi’s store, and within minutes she was on her way out the door with the copy in her hands. The odds of someone needing that obscure journal were infinitesimal (and that Mizrahi knew he had it, buried deep in his basement, astounding).

Even people who enter for trivialities leave hooked. There was the guy who came in looking for the bathroom and has since bought $60,000 worth of merchandise. Those seeking banned books can find them here, as well — Mizrahi has sold hundreds of copies of a book banned by many in Chabad, as well as staunchly Zionistic books that other stores shy away from.

From his tiny perch on Quentin Road, Mizrahi experiences the gamut of humanity. He regularly sends shipments to Japan, Dubai, Taiwan, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, the Philippines, Korea, Chile, Peru, and many other countries.

One of his Orthodox customers lives underground in a coal mine above the Arctic Circle six months of the year, and he buys a regular supply of seforim. Mizrahi shipped an entire ArtScroll Shas to someone in South Korea (“They’re fascinated with the Jewish mind over there,” he explains). In the American southwest, there are many people who believe — and have evidence — that they’re descendants of Marranos; they’ve developed an interest in Judaism, and buy books from him as well. He has a number of customers in jail or heading to jail; native Japanese who believe they’re descendants of the Lost Tribes; an Aramaic-speaking archbishop in Iraq who ordered a full set of Shas; chief rabbis, Knesset members, congressmen, and roshei yeshivah. A pastor in the Seventh Day Adventist movement who runs three churches in Queens has bought about 4,000 Jewish texts from him. Then there’s the wealthy Qatari oilman who bought dozens of Hebrew-language Satmar anti-Zionist books over the course of several years.

“I don’t know what he was doing with them, but I suspect it wasn’t good,” Mizrahi says. “I threw in a few freebies on Zionist history and the like, to give him a more balanced view.”

He has also come across really odd customers with bizarre theories and interests.

“When you’re dealing with a worldwide customer base, you learn that the world is weirder than you realized,” he says. The unusual and unexpected are all part of Mizrahi’s daily fare — “I do seem to attract such things, Heaven knows why.”

Not all Mizrahi’s customers actually care about books. An interior designer buys vellum-bound (calfskin) books by the foot; as long as they have the look of the time period he’s going for (eighteenth century Dutch), they could be Swahili inside. One customer buys only blue books, another only green. Mizrahi recently rented out 30 feet of books to be used as the background for a chuppah in New Jersey. He’s helped create sets for movies and theaters as well, building libraries that accurately reflect bookshelves of a particular era. “A popular film portrayed a Pesach seder scene of a Reform family in 1930s New York,” he recalls. “They came to me looking for a Hagaddah such a family would have had.”

His online space, judaicaused.com, is more intimate than a typical website — it encourages communication, and many longstanding relationships have developed. Birthday and shanah tovah wishes are de rigueur, and at least one non-Jew has wiggled his way into Mizrahi’s daily prayers.

“Deep in the Amazon, there was a Brazilian army helicopter pilot, his last name was Vital, a descendant of Marranos from the famous Vital family,” Mizrahi says. “He had a strong family tradition of not eating meat, marrying only within the family, and burying relatives in their own cemetery. I sent him books and we developed a friendship of sorts. When he died, I got a call from his son. He said, ‘My dad was interested in Judaism — it was his quirk. I’m Catholic and don’t know about this stuff, but Dad asked if you could say the Kaddish prayer for him.’

“And so I did.”

Mizrahi lent the Netziv’s copy of Rabbeinu Yerucham to the brave rosh kollel who published the first clear edition of this Rishon’s work in 500 years

Nuts and Bolts

A late-morning visitor to the store might see what appears to be a man at a cozy desk job; Mizrahi’s work is anything but that. Both arms of his enterprise — buying inventory and shipping orders — are labor intensive and physically demanding, and the hours are long.

After he closes at 7:00 p.m., Mizrahi gets in his van and heads out on house calls. He averages two to four a night, stopping at all sorts of places: the apartment of a recently deceased book collector whose family is selling his library, a shul that is forced to close its doors because the neighborhood demographic has changed, the home of an elderly couple who is downsizing. He’ll peruse the collection, sometimes purchasing the entire lot, while other times selecting items of interest; the average night nets him about 1,000 books. He and his assistant spend up to several hours putting together cardboard boxes, packing them with books, and loading them into his commercial van. His current inventory, which fills three crammed floors, stands at about half a million books.

“I’m very selective in what I take,” he says with a straight face.

By five a.m., he’s back in the store. He starts by packing and shipping out orders, about 150 on a typical day. Ninety percent of his merchandise goes to the same 100 customers, many of them online — these are the folks with continuous interest who drive his business on a daily basis. His regulars buy one or two books a week, spending $50 at most.

“As far as cost of habits go, book buying can be comparable to your daily Starbucks Frappuccino,” Mizrahi says.

Next up: cataloguing. Recently acquired items are photographed and described for the website before being assigned a specific spot on a shelf based on Mizrahi’s personal letter-number system.

“If someone puts a book back in the wrong place, it can be lost forever,” he says. (To prevent things from falling into the abyss, he limits visitors to a manageable three in the store at a time.)

Meanwhile, the yields from the previous night’s house calls have been waiting patiently in the van. When the day’s shipping and cataloguing is done, the street in front of the store turns into a bazaar as Mizrahi opens the rear door of the van to unload.

“In the morning, I reach out to customers who I think will be interested in my latest purchases and send them a heads up that I’ll be unloading at, say, two p.m. When I get a large library — for example, 1,000 books owned by a professor of Greek Jewry — I might have ten interested customers. Some come early, hoping to get first dibs. It tends to get intense — I’ve seen people pulling things out of each other’s hands,” Mizrahi recounts.

What survives the street scene is then divided into piles, with the interests of specific customers in mind, and whatever isn’t sold immediately goes into the next day’s cataloguing pile.

“It’s about knowing your customers, reaching out, and making shidduchim,” says Mizrahi. “One customer is excited by anything that was owned by Rav Meir Shapiro, there’s a calendar aficionado who wants anything calendar-related, a certain doctor is interested in medicine in Jewish history. One guy is interested in Jewish Algeria — with no Jewish community today, it’s a piece of the past — someone else in anything from the Proops printing press in 18th-century Amsterdam, another wants illustrations, and yet another wants anything written by his grandfather. Three people might want the same book, but for very different reasons: One is interested in the author, another in the subject matter, and a third in its provenance. When that happens, I offer it to the oldest of them, so I’ll get it back soon and resell it,” he jokes.

Sometimes perseverance wins out, as in the case of the guy who, as Mizrahi describes, “had an unhealthy relationship with books.” He was a book hoarder to the extreme.

“His son told me that when he’d come home from school, his mother would move piles of books from the bathtub to the bed so that he could shower, and then move them back to the tub so he could go to sleep. It got to the point where his wife told him it was either her or the books — and he chose the books,” Mizrahi says.

“He called me to his house multiple times, but each time I got there, he couldn’t bring himself to part with a single book. Eventually he died, and I bought all 500,000 books he owned — they filled 40 storage units.”

But, while house calls yield the bulk of his inventory, there are no sure bets.

“A woman called, going on and on about her huge library and what great books she had. I drove three hours to her house, but when I got there I didn’t see a single bookcase. I asked her where the books were, and she kept pointing to the air and saying, ‘Here they are!’ As I was leaving, a neighbor poked her head out. ‘I’m so sorry,’ he said, ‘she’s not well and she does this kind of thing regularly.’ ”

A significant slice of Mizrahi’s business involves buying and selling to institutions such as university libraries and museums. He bought 50,000 books from the Toronto Jewish Community Library when it closed in 2016, 10,000 from Hebrew College in Boston last summer, and thousands from Yeshiva University’s library in 2010, among others. The National Library of Israel (similar to the Library of Congress in the US) receives a copy of everything printed in Israel, and their aim is to acquire every Jewish-related book in print from anywhere in the world. Mizrahi sends them hundreds of books every month, some as seemingly irrelevant as pamphlets of sermons by unknown rabbis of yesteryear. Figuring out what they’re lacking requires a lot of work, but it’s also an opportunity to offload material he can’t sell. “And it’s fun,” he adds.

Every now and then, Mizrahi ends up with bonus material.

“A few weeks ago, I glanced at my security camera and saw a woman leave two boxes at my door,” he says. “By the time I got there, she was gone. Among the Chumashim and Israeli gift items, I saw something shocking — an urn filled with ashes! She left no contact information, so I waited for her to notice her mistake and come back for it. She never did, so I eventually I asked a rav what to do. Based on his direction, I took a shovel and buried it in a corner of the Jewish cemetery in Swan Lake.”’

Israel Mizrahi claims he can’t remember which three items to pick out in the grocery, but he can recall the location of any book among thousands

When Mizrahi set up shop 15 years ago, the book market was still a quiet one, which meant that pricing was somewhat arbitrary, and he had to feel his way through each deal. Today’s market is very lively — there are frequent auctions broadcast in glossy catalogues and reference books that provide pricing norms, so pricing is more straightforward: It boils down to what the market will bear.

He recalls visiting the home of a publisher in Israel who pulled out a dikduk sefer by the Radak printed in the 1400s — with a deep hole in the middle. The book had belonged to his grandfather, a Haganah fighter in the days leading up to the war in 1948, when the British would conduct house raids searching for Jews harboring illegal ammunition. His grandfather had cut a hole in the sefer and hidden a grenade in it.

“It’s hard to fathom cutting a book that valuable — it would be worth $15,000 today — but in the 1940s it was worth maybe $20, because Jews in general didn’t have money for luxuries, and there was certainly no market for old books,” Mizrahi explains. “Even today, a Christian book from the 1400s is worth only $300 to $500, because so much more was printed and survived. Their books didn’t get lost in book burnings and persecutions, plus the circle of collectors in that genre is small. That Jews are obsessed with books and will pay crazy money for them is a unique phenomenon.”

Age is just one factor that determines an item’s value. Today’s biggest market, Mizrahi says, is anything written by gedolim of the Chassidic world. Chassidus started out small — not much was published in its early days — and much of what was published was burned by its opponents — yet there are hundreds of thousands of chassidim today, and everyone wants the same first-generation books or anything printed by their Rebbe. There’s not enough to go around, of course, which sharply drives up prices.

A signed letter from the Lubavitcher Rebbe, for example, automatically sells for at least $1,000. There’s a letter from the Baal Shem Tov that is so faded the page looks blank and the text can only be seen under ultraviolet light. It’s on the market now with a seven-digit asking price.

Subject matter also drives the price. Any letter from Rav Moshe Feinstein will fetch at least $2,000, but if it’s a teshuvah he’s famous for, such as on chalav stam or eiruvin, it can go for five times that amount. Correspondence with another famous gadol increases the value of a letter.

“Rav Moshe’s correspondence with the Satmar Rebbe sold for $55,000,” he says.

In the early centuries of the Ottoman Empire, printing the Koran was considered a desecration of Allah’s name, punishable by death, and a ban was enacted on the printing of all religious material. This stagnated the Middle Eastern printing industry for hundreds of years, and extremely little was published, so a rare sefer from there is worth much more than one printed in Europe at the same time.

In the preprinting manuscript realm, on the other hand, almost all manuscripts extant today are from the Sephardi world — the Crusades, book burnings, and persecutions in Europe obliterated most of what the Ashkenazi world produced.

“For anything to have survived Jewish history is a miracle, and it did so only because of our passion for books,” Mizrahi says.

A collectible’s provenance, or record of ownership, has enormous influence on its value. Mizrahi cites the Bomberg Shas, the first complete set of Shas ever printed (in 1500’s Venice), as an extreme example.

“Original sets of the Bomberg Shas have generally sold for two to three million dollars. But a few years ago, a set sold at auction for almost ten million dollars. This set was owned by the British royal family, and all the hype around it drove up the price tremendously.”

Knowing a volume’s provenance also makes the experience of owning it that much richer. Mizrahi once purchased a sefer with an inscription from Hungary in 1944; there are records of its owner having been killed in Auschwitz just a few months later. Another time he opened a Hebrew Bible he acquired and was taken aback to see that a previous owner — somewhere in the American south circa 1840 — inscribed the names of his slaves into the empty last page.

Before every expensive purchase he makes, Mizrahi investigates the item’s provenance; he’s sometimes hired to do this for customers considering big-ticket purchases at auction houses.

“Anyone spending $100,000 on a manuscript will first make sure it’s clean. If there’s any suspicion it might have been stolen at any point along its journey, they’d have a hard time selling it down the road,” he explains. “Nobody wants to deal with a potential lawsuit.”

In one unfortunate circumstance, Mizrahi was on the cusp of brokering his largest sale ever — half a million dollars for a few handwritten lines by one of the greatest Rishonim (who can’t be identified to maintain the owner’s confidentiality). An investigation revealed an impeccable provenance from when it left the Cairo Geniza until it landed in a Russian library — but there the trail ran cold, indicating it was likely “borrowed” from the library during the Communist era and never returned. The potential buyer, of course, walked away.

Mizrahi tries to trace and validate an item’s entire ownership odyssey, turning to outside experts when needed. “If, for example, there’s a signature from Rav Chaim Vital, I send it to a Rav Vital expert to authenticate it. If a signature is hard to read, it’ll go to a handwriting expert; if an inscription is in Hungarian, I’ll show it to my Hungarian contact. There are experts on everything in the world — as they say, it’s not what you know, but who you know.”

Sometimes a sefer’s haskamah lends it the most interest. Mizrahi tells of a Shas he’s owned that was printed in Vienna in 1860, the first one with the Chasam Sofer’s commentary. It contains a haskamah from the Sanzer Rav, the Divrei Chaim; in it, he writes that the rav of Vienna, Rabbi Eliezer Horowitz, has kept a firm eye on the printing process and guarantees that there has been no chillul Shabbos during its production. It’s an unusual statement, but necessary for those living at the time, who shared a collective memory of a debacle that took place about 60 years prior.

At that time, another Shas was printed in Vienna, this one with the commentary of the Vilna Gaon for the first time. The editor was one Yehuda Ben Ze’ev, a maskil and Hebraist. A rav of renown, Rabbi Dovid Deutsch, harbored a suspicion that Ben Ze’ev was working on the project on Shabbos, so he and a few talmidim sneaked into the printing house one Shabbos to verify his hunch. Indeed, they caught the 47-year-old Ben Ze’ev hard at work. The story as printed in seforim recounts that Ben Ze’ev was so humiliated he ran to the bathroom to hide — and never came out. Alas, he died then and there. And so in 1860, in the next edition of Shas from that same printing house, the Divrei Chaim sought to reassure lomdei Torah that this edition wasn’t produced in sin. The haskamah and the story behind it doubled the set’s value, Mizrahi estimates.

Book-and-manuscript insiders often come to Mizrahi with their wish lists; he has a running list of over 10,000 items customers are looking for. Of course, seeking out a particular item can double its price.

“It’s better to just wait, and it will eventually turn up on the market,” Mizrahi advises, but if someone is desperate to lay claim to something that Mizrahi once sold to someone else, he might ask the owner if they’d be willing to sell it back.

How often do sales top $100,000? “I’ll tell you half in jest that Sephardic Jews are rather superstitious, so I don’t like talking about money too much. Let’s just say it happens regularly, but not often enough.”

Heart of the Matter

“When I read about Jewish life from the past — particularly the stories and experiences of individuals — I become nostalgic for a world I never lived in,” Mizrahi says. Books, he says, are the way to access that material and to better understand the miracle of Jewish existence, the evolution of our diverse traditions, and how we arrived where we are today.

Mizrahi has owned letters and original writings from the Shach (1600s Lithuania), the Bach (1500s-1600s Poland), Rav Shmelke of Nikolsburg (1700s Poland/Moravia), the Ben Ish Chai (1800s Iraq), Rav Yaakov Abuhatzeira (1800s Morocco), Moses Montefiore (1700s-1800s England), Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer (early 1900s Palestine), and too many others to recount.

As the consummate biblio-enthusiast, it can be challenging to let his most exciting acquisitions go. “But I’ve learned to control myself, and these days I only keep things of personal family interest. A book with my wife’s great-great-grandfather’s signature and stamp ended up in my store. He was from a small town in Morocco and owned maybe 20 books total, so it’s pretty miraculous,” he says. “I’ve also gotten books with my own great-grandfather’s signature in them.”

Hidden among large collections are relics of the past that can be downright distressing. From the Theresienstadt Ghetto/concentration camp library: the sefer Mechkarei Lashon, as well as sheet music used by the Jewish orchestra — chazzanus and Yiddish musicals from the New York Yiddish theater scene. As the model concentration camp, Theresienstadt’s library and orchestra showcased the rich cultural milieu the Jews were treated to in order to impress the Red Cross and visiting dignitaries.

On one occasion, he found a siddur published in Germany in 1933 with a prayer for Hitler in it. He’s owned a rabbinic journal from Hungary in 1943 that discusses the plight of European Jewry; it is painfully clear the Hungarian Jews had no inkling of their own impending fate. In it, the Klausenberg Rav, Rav Moshe Shmuel Glasner, lays out his proposed timetable for printing seforim over the next few years.

In 2018, while going through a 30,000-book collection he acquired, Mizrahi found himself holding a German book titled Statistics, Media, and Organizations of Jewry in the United States and Canada. It was stamped “For Internal Use Only.” As ordinary as it sounds, once Mizrahi understood what he was looking at, he went numb.

“This was published by the Nazi government in 1944, and the first page was stamped with Hitler’s bookplate — an eagle perched on an oak branch, clutching a swastika — telling me this book was his personal copy,” he says. “The 137 pages contained detailed lists and descriptions of every Jewish community in North America. The Nazis’ goal was to identify and take over every local organization in America that would have lists of Jews — and we know what their endgame was. Looking at this book, it became frighteningly clear to me: We are all survivors. That I bought it from a Holocaust survivor made it all the more chilling.”

The historical genre that most enthralls Mizrahi is personal correspondence from rabbanim that deal with the challenges of the communities they led. In June, he sold a letter that Rav Elchonon Wasserman wrote to a Russian philanthropist, thanking him for the arba minim he sent for the Jews of Baranovich (to paraphrase: “The esrogim are mehudarim, but the lulavim got banged around and arrived split.”) And using subtle hints, Rav Elchonon managed to thank the philanthropist for helping his son obtain a visa to travel to Eretz Yisrael to learn, thereby avoiding the Russian draft.

Mizrachi is fascinated by translations of sifrei kodesh into the vernacular. He was thrilled to acquire a siddur from the 1600s printed completely in Spanish. At the time, large numbers of Spanish Marranos began fleeing to Amsterdam, a newly accessible safe haven, to reestablish their Judaism. Having lived as Christians for a few generations, they didn’t know Hebrew, and printing siddurim and Chumashim in Spanish became a communal priority to help ease them back into the fold. In contrast, there was no printing of sifrei kodesh in Ladino or Arabic at all at the time (even though large segments of those populations couldn’t read or understand Hebrew). In fact, when translations were printed in those languages many years later, the introductions were full of apologies and explanations as to why it was necessary due to the times.

At 11:56 p.m. one night as this article was being prepared for print, Mizrahi sent a voice note. His voice was calm as usual, but with a detectable undertone of excitement.

“Sorry for the late timing, I’m still here in the store with customers,” he says. “I just got this absolutely fascinating letter written by Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski from Vilna in 1938.” He continues to explain that this was the year before Rav Chaim Ozer’s passing. At the time, the Conservative movement in New York, in an effort to end the agunah issue, was pushing to add a codicil to kesubos that would empower a woman to write her own get under certain specified circumstances. Rav Eliezer Silver, Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, and others on the Vaad Harabonim of America fought against it. Rav Chaim Ozer heard that a prominent Sephardi Rabbi and mekubal in Yerushalayim was in favor of it, and he penned an impassioned letter to the Vaad Harabbonim querying, “Is he a mekubal or a metoraf (i.e., crazy)? [The mekubal-metoraf terminology is a play on words from a gemara in Berachos.] Please write to him and set him straight.”

On one occasion, Mizrahi merited the unique opportunity to fill a gap in the historical record. Back in the days when paper was rare and expensive, people would utilize the empty first and last pages of books to record family births and deaths, chiddushei Torah, or anything else of importance. Mizrahi acquired an 18th century German-printed machzor, and the three empty pages in the back contained a handwritten kinnah, in lyrical Hebrew prose, describing a pogrom that took place in Poland on the second night of Pesach, 1655. It includes the names of the murdered and the way they were killed: “Rabbi Yitzchak, the head of the beis din… they ripped his beard and threw him from the windows to the trash,” and “Rabbi Israel who was from the tribe of the Levites. The enemies placed fire and sulfur on the heart, and his soul exited as he said the verse Shema Yisrael.”

There is some debate if the pogroms associated with the Chmielnitzki Uprising (Gezeiros Tach v’Tat) ended in 1654 or 1657, and this kinnah proves that pogroms continued after 1654. Mizrahi searched the references and found no mention of this pogrom anywhere else, making this kinnah an important historical document; by posting it online, he actively contributed to the historical record.

Pressed for an extra-exciting find, Mizrahi offers, “Do you want to hear about something really awesome? A guy in Queens inherited his grandfather’s books, and he sold them to me. In one of the boxes I found a handwritten, autographed manuscript. It was peirush on Megillas Esther by Rabbi Chaim HaKohen of Aram Tzova, a talmid of Rav Chaim Vital living in Aleppo, Syria (1585-1655). I immediately knew I was looking at something special, because I was familiar with another one of Rabbi HaKohen’s seforim published in 1640, in which he tells the following story.”

Rav HaKohen writes that he sent his peirush on Megillas Esther to Venice to be printed, but the manuscript was lost en route. He rewrote the sefer, and to be safe, he decided to personally bring it to the printing house in Venice. His son accompanied him on the journey. To their distress, pirates boarded the ship they were on, and they jumped overboard. Miraculously, they both made it to dry land, but the manuscript was left behind. They arrived in Venice penniless, where Rav HaKohen proceeded to write the peirush yet a third time. For reasons lost to history, though, the peirush never made it to print.

There has been one version of the handwritten manuscript in circulation over the years which appeared ready for print, with an introduction, page numbers, and an index. “The logical assumption is that copy is the one rewritten in Venice, because that copy is the most likely to have survived,” Mizrahi says. Which leads him to suspect that the copy he found is the one left behind on the ship, or perhaps the first version which was lost on its way to Venice. Neither was a copy of the other, as there are significant differences between them.

Mizrahi’s copy had just one ownership marking, that of the rabbi of the Balkan town of Monastir. The town’s Jewish community was completely eliminated by the Nazis, but the rabbi moved to New York before the war, and his library ended up at Yeshiva University. The manuscript’s whereabouts in the three preceding centuries will likely remain a mystery.

We can infer the sefer written in Venice was not published because through the 1600s, printing was a laborious and expensive process. “That being the case, they’d always print at least 1,000 copies, to make it worth the cost. Because of that, almost no printed books have been lost to us from that period,” Mizrahi explains. “With time, printing became cheaper, and it became possible to print just 50 — or even two — copies of a book. Many such publications from this later period have been lost. Also, Rav HaKohen’s eight published books are widely quoted in other seforim, but there’s no mention of this one, another indication it never made it to print.

“Finding a 1600s manuscript of an entire sefer that’s never been exposed — no scholar or rav ever mentioned this peirush — and that had been sitting on a shelf in Queens for two generations is like creating something from thin air,” Mizrahi says.

Mizrahi also appreciates the global Jewish community books can represent. He pulls out a sefer Tachkemoni, written by Spanish Rabbi Yehuda Alharizi in the 1100s and printed in Vienna in 1854, to illustrate his point. “This book was written in Spain, printed in Austria, and has a German translation. The original ownership marking is the signature of the founder of the first printing press in Syria; next comes the stamp of the Chief Rabbi of Beirut, and now it’s in my store in Marine Park, Brooklyn. That’s quite a clash of cultures!”

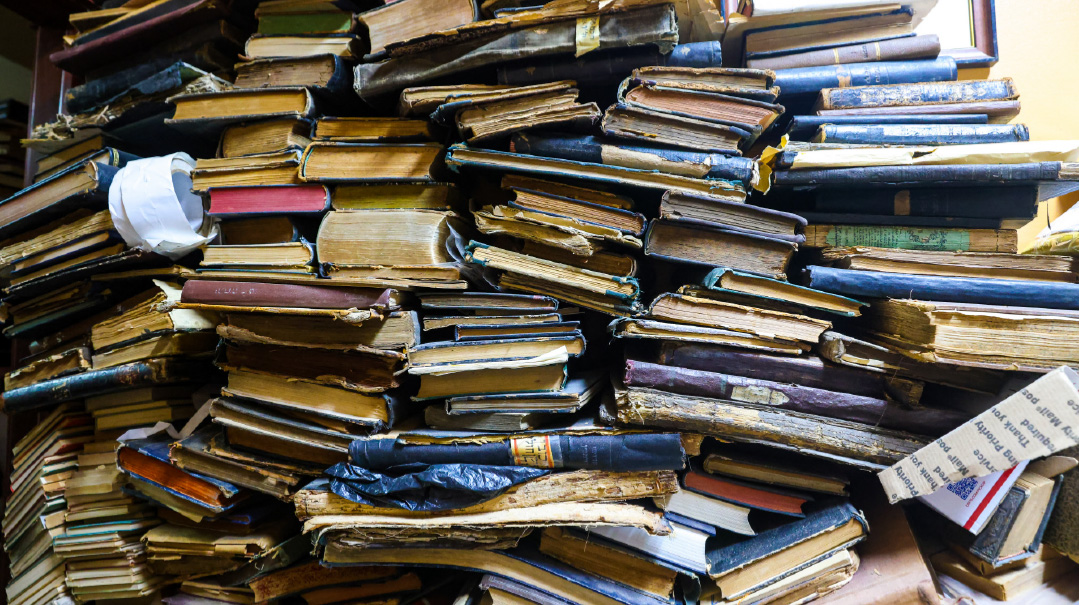

Mizrahi asserts that it’s a miracle that any manuscripts have been preserved through the travails of Jewish history

The oldest item Mizrahi ever held is a scrap with a few lines in the Rambam’s own hand, written in the 1100s, which somehow made its way from the Cairo Geniza to the open market.

He’s had a few loose pages from a Gemara carbon-dated to the 1200s, an exceedingly rare find, especially since it wasn’t from the Cairo Geniza. Anything to have survived that long has a story, and the story of these pages is their years residing in the binding of a Christian book.

“In the first few centuries of printing, book bindings were sometimes reinforced by being stuffed with the leaves of discarded manuscripts — this is one way some ancient manuscripts managed to survive,” Mizrahi explains. “There are professionals today who take apart old bindings, looking for papers within them.” This is known in the book world as “books within books.”

He’s also owned a complete manuscript of the sefer Ohr Zarua from the 1300s, a handwritten copy of the original, which was written by the author about a 100 years earlier.

Ancient manuscripts can hold up over the centuries, depending on their era.

“Believe it or not,” Mizrahi says, “manuscripts from the Middle Ages are better preserved than those from the mid-1800s and later, because they were written on rag paper — created literally from cloth rags — which can last forever. Books were the province of the wealthy and were of very high quality. Starting in the 1800s, paper made from trees became the norm, and manufacturing additives made the paper acidic, which contributes to deterioration over time.”

As ancient manuscripts have been copied over the years, mistakes inevitably crept in. Since paper was expensive, shorthand symbols were devised to save space, such as a dot at the end of a word replacing the “yud mem” signifying plurality. Such symbols, and others, like roshei teivos, made way for errors. Sometimes an individual’s personal notes in the margins were accidentally incorporated into the next generation of text. Take Targum Onkelos, written in the times of the Tannaim; it’s not surprising that there are at least five or six versions of manuscripts, and even more than one printed version. (The oldest version extant today is about 1,000 years old, but of course that was copied from an even older version.)

Mizrahi has owned a full printed sefer of the Ramban on Chumash from 1490 from the earliest days of Hebrew printing. (The first Hebrew printing took place in 1470, about 30 years after the invention of the printing press.)

In some parts of the world, what appears ancient might actually be fairly modern. Atop a waist-high stack of books in the middle of Mizrahi’s store sits a Taj, a uniquely Yemenite compilation that includes Torah, Onkelos, and the peirush of Rav Saadia Gaon in Judeo-Arabic, with each Torah verse followed by the two peirushim in the text itself. This particular Taj is from the 1800s, although at first glance it could pass for a medieval manuscript: It’s handwritten — printing didn’t come to Yemen until the 20th century — and even more striking, the nekudos are found above the words (known as Babylonian vowels) rather than below them (Tiberian vowels). “Both forms of nekudos were developed at around the same time, in the 700s,” Mizrahi says. “But the use of Babylonian vowels died out after a few centuries everywhere except in Yemen, where it was used until fairly recently.”

The Memory Keeper

At least to this visitor, the most impressive entity in the store is Mizrahi himself. Each volume or document in his possession tells its own story, and Mizrahi is the repository for them all. His knowledge of Jewish history is encyclopedic — ask him a question about any part of the world in any time period, and he’ll spew out dates, facts, the geopolitical context and its impact on Jewish life, the cultural milieu, gedolim who lived there, the sh’eilos and teshuvos of the time, demographic trends, the geographic borders at the time, and just about anything else that is relevant.

Mizrahi’s wit is as sharp as his memory is remarkable. A number of years ago, a delegation from the Orthodox Union scheduled a meeting with Binyamin Netanyahu, and they wanted to bring a unique gift along. Knowing that many years earlier Bibi’s father, Benzion Netanyahu, had written a book Don Isaac Abravanel: Statesman and Philosopher, Mizrahi cleverly suggested two first-edition Abarbanels — one on Sefer Yehoshua, and one on Pirkei Avos (printed in 1511 and 1506, respectively). He selected those because Yehoshua was the statesman who set up the Jewish commonwealth in Eretz Yisrael, and Pirkei Avos is a philosophical work. Of course, Mizrahi had both rare first editions in his store. Bibi was extraordinarily moved by the gifts.

But for all Mizrahi’s intellectual gifts, it’s his raw memory that wins him the gold — and you can test it out yourself. Choose a random stack of books in his office in varying shades of weathered brown, and point to one book in the stack.

“Oh, that’s a book with internal paperwork from Chabad headquarters in the 1940s and 50s. It contains draft deferment letters for each of their talmidim,” he will instantly inform you.

Point to another brown volume in another floor-to-ceiling stack. “That’s an old Vilna machzor, printed in the 1860s. The lighter brown one to its right is a Berditchev Shas from the 1880s, unique in that the entire Shas is printed in one volume, in a non-traditional format.”

As to how he recalls the location of any one volume among many thousands?

“Because I put it there,” Mizrahi says nonchalantly.

But his memory isn’t photographic — in fact, he maintains, it’s nothing special at all — he just remembers things that interest him, “like anyone else.” Because what he reads fascinates him, it sticks — all 2,000 pages a week of it.

“But when I’m at the supermarket,” he says with a shrug, “I can’t remember the three things I’m supposed to buy.” —

From the Land of Stars and Stripes

For all the bounty originating from the far corners of the globe, Americana buffs will find many hours-worth of treasures to sift through at Mizrahi Bookstore.

“Every New England town had a kehillah of shomrei Torah u’mitzvos in the early 1900s,” Mizrahi says. “The items that come into my store give a real flavor for how vibrant community life there was.”

For example, he has a handwritten peirush on Pirkei Avos from a rav in Auburn, Maine, from 1928, whose shul, Beth Avraham, was founded by Russian and Polish Jews.

“The peirush is quite lomdish, clearly meant for a learned audience,” he says. “By chance I also came across this same shul’s newsletter and discovered they had two Shacharis minyanim daily, as well as early and late Maariv. Almost every New England town had societies for Ein Yaakov, Mishnayos, and more, but there’s little memory of these places today” — except for at Mizrahi Bookstore.

Come see the pamphlet that came in the glove compartment of new Ford Model T in the early 1900s, written by Henry Ford himself, who was doing his civic duty by warning good Americans of the vast Jewish conspiracy to control the world through fomenting world wars and other nefarious tactics.

Or peek into the window of turn-of-the-20th-century synagogue life by browsing their constitutions: “No alterations that are conflicting with the… Shulchan Aruch shall be made in the daily prayers, ceremonies or customs… as long as one member of this congregation shall oppose it” (Congregation Beth Hamedrosh Hagodol of Washington Heights).

“Marriage contrary to the laws of the Jewish religion… or conduct injurious to the cause and welfare of our ancient faith and race shall be deemed ample grounds for expulsion from membership” (Congregation Mishkan Tefila, Boston, 1913).

“In the case of the death of a member, the Congregation will provide a plot in our cemetery, a hearse with two carriages…” (Congregation Agudas Israel of Ridgewood, Brooklyn).

And the more prosaic: “That all umbrellas and canes, excepting canes carried by lame persons, shall be left at the door, and that all garments taken off shall be deposited in the free seats near the door, unless the owners thereof put them in their own seats” (Congregation Shearith Israel, New York City).

The crown jewel of Mizrahi’s Americana collection is his super-rare copy of the Journal of the Proceedings of Congress from 1776, the first session of Congress after American independence was declared. “The printer writes that he sold 80 copies, and the rest were torn up to produce rifle cartridges for the American Revolution,” Mizrahi says. “Of Jewish interest is mention of one Michael Gretz, a Prussian Jewish businessman who lent money to the Revolutionary Army; the journal discusses his negotiations with the Indians.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 980)

Oops! We could not locate your form.