Still Together

More than two decades after their father’s passing, the four sons of legendary MK Avraham Yosef “Munia” Schapira are still living his legacy

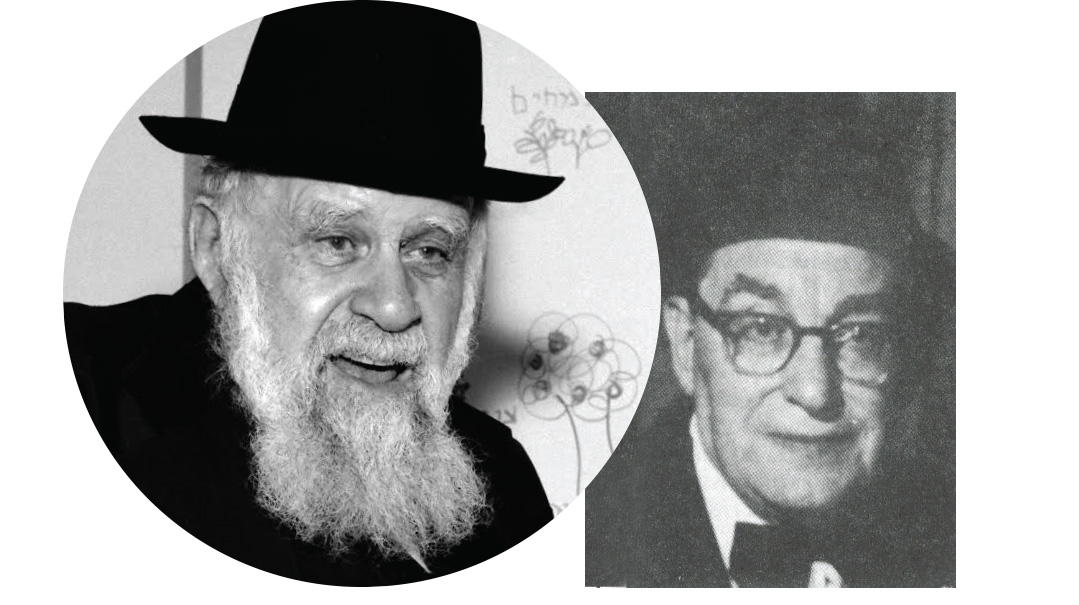

Photos: Mishpacha archives

If you pass by the house on 20 Stricker Street in northern Tel Aviv, you might mistake it for an embassy or some kind of international headquarters. Sleek luxury cars glide into the parking area, nattily-dressed security guards jump up and open doors to powerful VIPs, and there seems to be a constant flow of service providers and secretaries going in and out. That wouldn’t be so unusual for a luxury home of some powerbroker, but here, the master of the house has not been in This World for more than 20 years. Still, the house is humming. Business goes on. For his sons, it’s still the center of their world.

Agudah MK and business magnate Rabbi Avraham Yosef (Munia) Schapira a”h used to say that Tel Aviv, where he made his home, is the holiest city in Eretz Yisrael because it’s the only one without a church. And his best friend, neighbor, and mechutan, the Sadigura Rebbe ztz”l who passed away in 2013 (his daughter married Rabbi Munia’s son Rabbi Pinchas Schapira), insisted on keeping his court there so that the city shouldn’t become an ir nidachas (an idolatrous city slated to be destroyed).

It’s no wonder, then, that the palatial villa on Rechov Stricker 20 still serves as the central headquarters of the Schapira clan more than two decades after patriarch Rabbi Avraham Yosef passed away, and is where London-and-Swiss-based millionaire son Rabbi Yitzchak Yehudah (Isaac) Schapira stays during his frequent trips to Israel.

Few Israeli politicians were able to navigate the secular-religious divide with more skill and savvy than MK Schapira. His schmoozy, easygoing persona belied his political and financial acumen, and his large girth, perpetual cigar, and fly-away peyos escaping from under his yarmulke only added to his colorful image. Yet he was Agudah’s master tactician, having chaired the influential Knesset Finance Committee, headed the Bank of Israel advisory board, and is largely credited with pulling the country out of its economic morass in the early 1980s. His multi-million-dollar Carmel Carpets enterprise eventually floundered, but he recouped his losses in real estate and other holdings, which today are managed by his sons Pinchas and Elimelech in Israel, Shmuel in Vienna, and Yitzchak in London and Switzerland.

The magnificent seforim-lined walls with a built-in aron kodesh are still there, and so is Reb Munia’s leather chair — although none of his sons will ever actually sit in it. Even Shaul, the veteran gabbai and driver employed by Reb Munia decades ago, still runs the household. His hair is grayer, but he’s as loyal to his boss as he was before 23 Sivan, 2000, when Reb Munia was niftar. He still won’t share any of the secrets that took place here — not about the conversations with Rabin, the deals with Arik, the brokered coalition talks, or the meetings with mayors, tycoons, rebbes, and directors of Torah institutions. Instead, he makes sure to replenish the large jug of oil used to fill the continually-burning lights in honor of Reb Munia and his almanah, Tova Sheindel, who passed away in 2017. (Tova Sheindel Schapira was the daughter of the Cheshev Sofer, the last of the Sofer dynasty to serve as rav and rosh yeshivah in Pressburg, who came to Eretz Yisrael penniless yet made a fortune from some well-placed oil investments).

But the true heirs to Rabbi Schapira's legacy are his four sons, today grandfathers themselves. They all proudly carry the Schapira brand — in dress, speech, and conduct.

The four brothers are spread out between London, Zurich and Vienna, Tel Aviv and Caesarea, yet the house on Stricker Street remains a base for their business and philanthropic activities (two sisters live in New York).

The oldest son is Rabbi Pinchas Schapira, son-in-law of the Ikvei Abirim of Sadigura ztz”l, and the rav of Sadigura beis medrash in Tel Aviv.

The second is the renowned askan and philanthropist Rabbi Yitzchak Schapira of London, Zurich, and Jerusalem. A noted philanthropist with significant international political clout, Reb Yitzchak inherited his father’s negotiation finesse as well as his trademark fly-away peyos. But the chassidishe look didn’t impede his being a 2014 recipient of one of Queen Elizabeth’s highest honors, the Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for “strengthening the ties between the UK and the chareidi community.” He is also known for his global efforts to save the burial sites of gedolim in Central and Eastern Europe, and was intimately involved behind the scenes in helping to free Sholom Mordechai Rubashkin.

The next son is Rabbi Elimelech Shraga Schapira, rosh kahal of Sadigura, and a noted author, historian, and family record-keeper; followed by Rabbi Shmuel Binyamin Schapira, who lives in Vienna, Austria, serving as the city’s rosh kahal. Each runs a financial empire of his own, but is also a partner in the family business. And each see their father as their inspiration.

Oops! We could not locate your form.