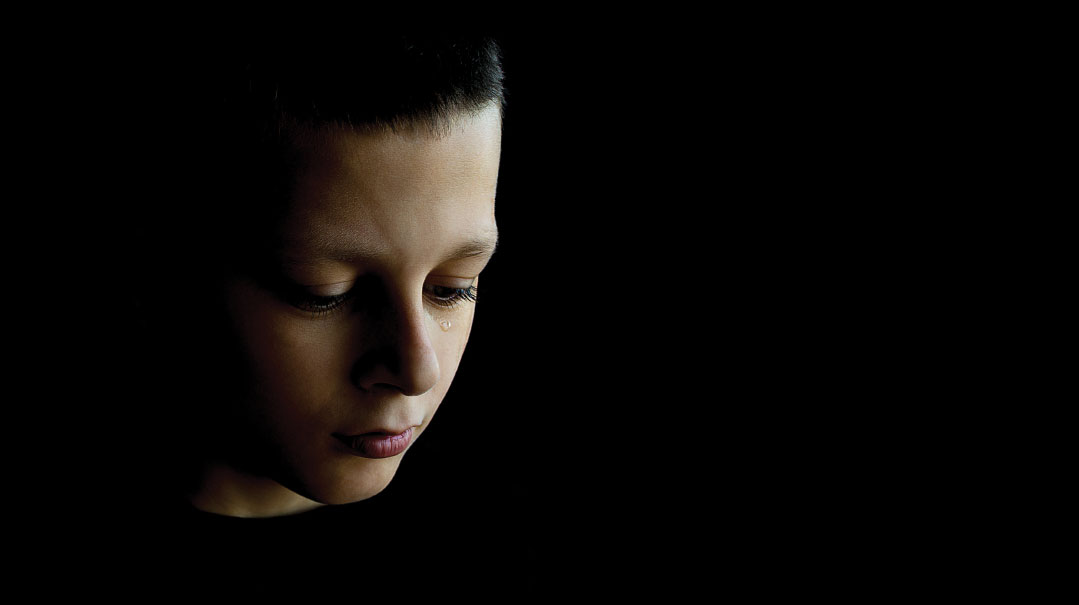

Silent Mourners

If ever there was a situation of b’makom sh’ein anashim, hishtadel lihyos ish, I thought to myself, this is it

In the close-knit chassidic community in Ramat Beit Shemesh that my family and I belong to, my ten-year-old son, Shimmy, was best friends with another boy, a lively, energetic kid whom I’ll call Yitzi.

The cheder that Shimmy and Yitzi attended was situated on our sleepy, dead-end street, and all the other boys on the block attended this cheder as well, so they all knew each other and played together. But Shimmy and Yitzi had a special bond — it was always Shimmy and Yitzi, Yitzi and Shimmy.

One Monday afternoon, the quiet of our residential street was shattered by the wailing of sirens as ambulances, police cars, and fire trucks converged in front of the building where Yitzi lived. Curious to see what was going on, Shimmy hurried out onto our porch and called down to one of his friends below on the street to find out what the commotion was about.

“Something bad happened to Yitzi,” the friend called back up to him.

Shimmy raced downstairs and down the block, where a throng of kids had already congregated and were watching as paramedics moved a limp Yitzi onto a stretcher and into an ambulance.

Later that day, we heard the horrific details of what had happened. Yitzi had been playing with a rope, which somehow became wound around his neck, choking him. He was found unconscious and rushed to the hospital, where he was pronounced in critical condition.

From the moment Yitzi was taken away by ambulance, Shimmy opened a Tehillim and did not stop davening and crying. Minyanim were convened in shuls throughout the neighborhood for people to say Tehillim, and, instead of playing, the children sat and said Tehillim as well. The next morning, when I entered Shimmy’s room to wake him, I saw that even in his dreams his lips were murmuring words of Tehillim.

While the adults in the neighborhood were whispering, “Is Yitzi going to survive?” the children were innocently asking, “When is Yitzi coming home?” They could not even conceive of the possibility that Yitzi, who was always so alive, might never come home.

The parents of Yitzi’s friends did not know what to tell their kids. Some put on a confident face and assured their children that Yitzi would soon be discharged from the hospital. Others gave vague answers regarding his prognosis.

Early Friday afternoon, the terrible news came: Yitzi had passed away.

Trained as I am as a psychotherapist, I knew I had to be the one to tell Shimmy what had happened. Still, professional training notwithstanding, informing your own young son that his best friend just died is a gruesome task.

Not wanting Shimmy to hear the news from the other kids, I hurried out to the street to find him, and I told him that I needed to talk to him.

I led Shimmy down the block to my office and said, in a low voice, “Shimmy, I have something very, very difficult to tell you.”

Grasping immediately what it was I was about to say, he screamed, “No, Abba, no! Don’t tell me!”

I seated him on my knees, waited for him to calm down somewhat, and then told him the bitter news.

Shimmy slumped back on the couch in my office and started to weep inconsolably. Then, as the tears poured from his eyes, he began to sing the Yiddish song “Neshamah Vi Bist Di,” substituting the original lyrics with his own: “Yitzi vi bist di; Yitzi, ich vart azoi lang oif dir.” I helped him add the words, “Yitzi, daven far mir beim Kisei Hakavod,” and he then continued, “Oy, oy, Yitzi vi bist di, azoi veit in himmel bist di, Yitzi daven far mir beim Kisei Hakavod.” I joined him in singing this song again and again.

Recognizing that he would need to process the loss by talking about it, I told him to call my parents, his grandparents, to tell them the news. Then, after he cried on the phone to them and they tried to comfort him, I told him to follow me out onto the street so that he could meet his friends and share these difficult moments with them.

Outside, a heartrending sight met my eyes. The kids, all of whom knew Yitzi and many of whom were his classmates, were roaming the streets in a state of shock and terror. One kid was screaming, “Oy! What happened to Yitzi?” Another kid was sitting inside his house, at the window facing the street, and howling wordlessly. A third was running in the middle of the street like a madman.

Some kids were just standing silently, tears streaming from their eyes.

As I beheld this scene, my phone rang. It was another father from the block, calling frantically to ask me what to do. “Aharon, my son locked himself in the bathroom, banging and screaming, and he won’t come out,” he cried. “He’s going crazy!”

In the meantime, the adults from the neighborhood were hurrying to travel to the levayah, which was being held in Yerushalayim before Shabbos. Some were climbing into their own cars, while others were trying to find rides. I myself do not own a car, so I told my wife that I planned to look for a ride to Yerushalayim.

While searching for a ride, I noticed a neighbor of mine pulling away in his car while his young son was screaming, “Tatty, I want to go to the levayah! Yitzi is my friend! What do you have to do with him?”

“No,” the father replied. “Children don’t belong at a levayah.”

“But I want to say goodbye to Yitzi!” the kid wailed.

The father simply drove off, leaving his son crying hysterically at the side of the road.

All around me, parents were hurrying away to the levayah, leaving the children basically alone.

These kids can’t be left here by themselves, I thought. Other than Yitzi’s immediate family, his friends were the ones most affected by the tragedy, and I knew it would be a horrible mistake for the adults to abandon them to their grief.

But I also had to go to the levayah. Yitzi’s father was a good friend of mine, and I belonged at the levayah with him, just like the other parents on the block.

What was I supposed to do? Go to the levayah like all the other parents, or stay here with the kids?

As I deliberated, car after car pulled away, and I realized that my chances of catching a ride were dwindling. This was it — I had to stop thinking and just jump into a car so that I could pay Yitzi his final respects and be there for his parents in their most anguished moments.

But then I thought of an old client of mine, whom I’ll call Avrumi.

Avrumi had entered my office at the age of 32 with a long history of self-destructive behaviors, stormy relationships, and failure to hold down a job or stay in a marriage. During our sessions, he told me that he was a child of divorced parents, both of whom were dysfunctional, even abusive. The only place in the world where Avrumi could find love and safety was with his grandmother, whom he was very close to, almost like a son. When she died, Avrumi was left a living orphan, with no one to love or care for him.

At the levayah and shivah, however, Avrumi had no place. He was just another grandchild, and while everyone was busy comforting the aveilim and catering to them, he got shoved to the side and ignored. Yet although he was not technically an avel, he was probably the one most devastated by the loss. With his grandmother’s death, his life spun out of control, and he began to view the world as a dangerous, unpredictable, frightening place.

Avrumi had never made any connection between his grandmother’s passing and the troublesome behaviors he subsequently fell into. But I sensed that the unprocessed loss was likely at the root of all the other issues he was experiencing, so instead of tackling his presenting problems directly, I told him that we were going to sit shivah for his grandmother. We sat on low chairs in my office, talking about his Savta and crying together over his utter abandonment.

It was the first time in his life that anyone had ever comforted him over the loss of his Savta. From there, the road to his healing began.

Looking at the bereft children in front of me, I realized that every one of them could potentially become an Avrumi. They were not going to sit shivah and would not benefit from a stream of visitors coming to comfort them. Sunday morning they would be back in cheder, and while the rebbi and menahel would undoubtedly speak some words of chizuk to them, and perhaps even bring in a professional to help them with their grief, no one — absolutely no one — was here, right now, to guide them and help them find some comfort while their friend was being accompanied to his final rest.

Still, how could I be the only father in the class absent from Yitzi’s levayah?

If ever there was a situation of b’makom sh’ein anashim, hishtadel lihyos ish, I thought to myself, this is it. Their world has just fallen apart, and they need an adult to help them make sense of what’s happening.

Turning my back on the last of the cars heading to Yerushalayim, I walked over to Shimmy, who was standing with two of his friends, and told them to let the entire class know that they should come to my office at 3:45, which was the scheduled time of the levayah. “We’re going to hold our own levayah right here,” I informed them.

When the boys filed into my office at 3:45, I somberly informed them that we were going to mourn for the tzaddik who had just died. I instructed them to sit on the floor like aveilim, and I closed the light in my office, leaving the door slightly open so that some light came in from the hallway. I put numerous packages of tissues around the darkened room, and began describing to the boys what was happening to Yitzi.

“Yitzi’s body is being placed in the ground now,” I said, “but his neshamah — which is the real Yitzi — is going up to Shamayim, right near Hashem. There’s a special, high place up there for tinokos shel beis rabban, who are free of aveiros, and Hashem wanted Yitzi, the tzaddik, to be in Shamayim with Him. Right now Yitzi is safe and very happy. We miss him, but he isn’t missing anything.”

That was step one — assuring the kids that Yitzi was in good hands, while quelling any fears and worries about what was going on with him now.

The next step was to talk about what had happened and let each of the kids express their own narrative of the tragedy.

“How did you hear the terrible news?” I asked them. I gave each one a chance to describe where they had been when they heard about the accident, who had told them, and what information they had been given. After they each related the technical details of how they had learned of the accident, I asked them to describe how they had felt when they had heard about it and how they had felt when they later heard that Yitzi had passed on.

“It’s hard for me,” one boy said simply.

“I can’t believe that this happened,” another one said. “I really think Yitzi is going to jump up in the middle of the levayah and come back here to us.”

“I didn’t stop crying from the minute I heard what happened to Yitzi,” a third boy admitted.

“I feel like my head is spinning,” a fourth boy shared.

“What’s going to happen now to all of Yitzi’s stuff?” yet another kid wondered.

Each of the kids was relating to the tragedy in a different way: some were fighting the reality of what had happened, some were grappling with intense emotion, some were experiencing physical manifestations of shock and grief, and others were obsessed with technicalities. The boy who asked about Yitzi’s stuff could not stop thinking about what would happen to his clothing, his knapsack, his toys. Would they be given away to some other child? Would they be unceremoniously discarded? Would they be preserved in his memory?

As I listened to their responses, I tried to validate all of them, expressing empathy for the individual difficulties each boy was facing and giving them the sense that whatever they were thinking and feeling about the tragedy was legitimate. I told them they could ask any questions and gave truthful answers, to the best of my ability. To the major question of “how could this happen,” I responded that Yitzi had evidently completed his tafkid in this world and had accomplished whatever tikkun his neshamah required. I added that Friday afternoon is a time when big tzaddikim are taken from this world, for the Gemara says that it is a good sign for a person to pass away on Erev Shabbos.

“It’s a mitzvah to cry for a tzaddik who died,” I told them, “and it’s okay if you feel like crying.” Some of the kids were already crying before I said this, but after I said these words I saw the strongest kid in the group, the one least likely to cry, cover his face with his hands and burst into tears. I sat there and cried with them.

To help the children give expression to their turbulent feelings, I began singing the song that Shimmy had spontaneously composed: Yitzi vi bist di; Yitzi ich vart azoi lang oif dir; Yitzi, daven far mir beim Kisei Hakavod. Some of the boys who had trouble expressing themselves verbally were able to pour their emotions into the lyrics, visibly achieving emotional release as we sang the song over and over again, both in its original form and with the new lyrics.

Next, I asked the boys to each say something that they could learn from Yitzi. As we went around the room, most of the boys talked about how kind Yitzi was and how he loved to give to others.

Now that the atmosphere in the room had changed, with the focus shifting from grief to positive memories of Yitzi, I began singing a more uplifting song: K’racheim av, k’racheim av, k’racheim av al banim, kein teracheim Hashem aleinu. Tatteh, mir farluzen zich nur oif dir….

When we finished singing, I told the kids, “Now we’re going to do the levayah.”

“But Yitzi is not here!” they protested.

“It’s true that his body is in Yerushalayim,” I said, “but his neshamah is with us, and he wants to say goodbye to you, his friends. You don’t see him, but he’s here, and your presence means more to him than your parents’ presence at the actual levayah.

“What do we do at a levayah?” I continued. “First, we say Vihi Noam, davening to Hashem that the niftar should find rest in the Olam Ha’elyon.”

I recited the Vihi Noam prayer word for word, and the boys repeated each word after me.

“Now we’re going to ask mechilah from the niftar,” I said. I instructed the boys to each ask Yitzi for mechilah for anything they had done to him, knowing that this would help them to move past any guilt they might be feeling over whatever negative interactions they’d had with him. Harboring anger or resentment toward the niftar can also affect the healing process, I knew, so I encouraged the boys not only to ask mechilah from Yitzi, but also to state that they forgave Yitzi for wronging them in any way.

With ten-year-old purity and innocence, the boys each asked Yitzi to forgive them and then declared, “Yitzi, I forgive you for everything.”

With that, our levayah ceremony was over.

“Now, Yitzi is in Shamayim,” I said. “And now you can all go home and enjoy Shabbos. Yitzi is happy, and he wants you to be happy, too.”

That Friday night, a few fathers approached me and asked, “What did you do for my son? He was going out of his mind earlier today, but he came home from your office calm and at peace.”

“I sat with the boys and helped them face their grief and process the tragedy,” I replied.

Children are capable of handling even the most difficult experiences, as long as the emotional aspect of those experiences is not overlooked or dismissed. Yet so often, the reaction of adults to difficult, even wrenching experiences that children go through is to “not make a big deal about it.” Whether overtly or subliminally, they convey to the child that he needs to move on and forget what happened. But the psyche doesn’t forget traumatic events or losses, and if the child is not encouraged to face what happened, understand it on his level and feel the gamut of emotions triggered by the experience, then the unresolved grief festers subconsciously, often finding expression in unhealthy behaviors and causing the child untold suffering throughout his life.

“I’ve seen too many clients in my office struggle to process grief from long-buried childhood losses,” I told the other fathers. “I didn’t want Shimmy and his friends to have to shlepp that burden with them for years until they’d find themselves in the office of a therapist who could finally help them release that burden.”

I encouraged Shimmy to do things l’ilui nishmas Yitzi, so that he would feel that he was doing something good for his friend, and he established a Chevras Tehillim and a Chevras Mishnayos in his memory. He and some friends also collected money for a fund that distributed candies and treats to needy boys.

At first, he was busy with these activities practically all day, but as time went on he became less busy with them. Today, three years later, he is no longer overwhelmed with emotion when the topic of Yitzi’s death comes up, and I can talk to him about the loss without triggering feelings of grief. He tells me that the same is true of his friends as well.

My spontaneous decision to stay home with the kids and hold a quasi-levayah while all my neighbors were heading to the real levayah was not an easy one. But in choosing to focus on the silent mourners — Yitzi’s friends, who would not be sitting shivah — I, and they, were able to truly pay our last respects to Yitzi’s departed neshamah.

The narrator, Aharon Lerner, may be contacted through LifeLines.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 826)

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (4)