Requiem for Labor

“The big absurdity is that Labor’s actual positions enjoy majority support among the Israeli public"

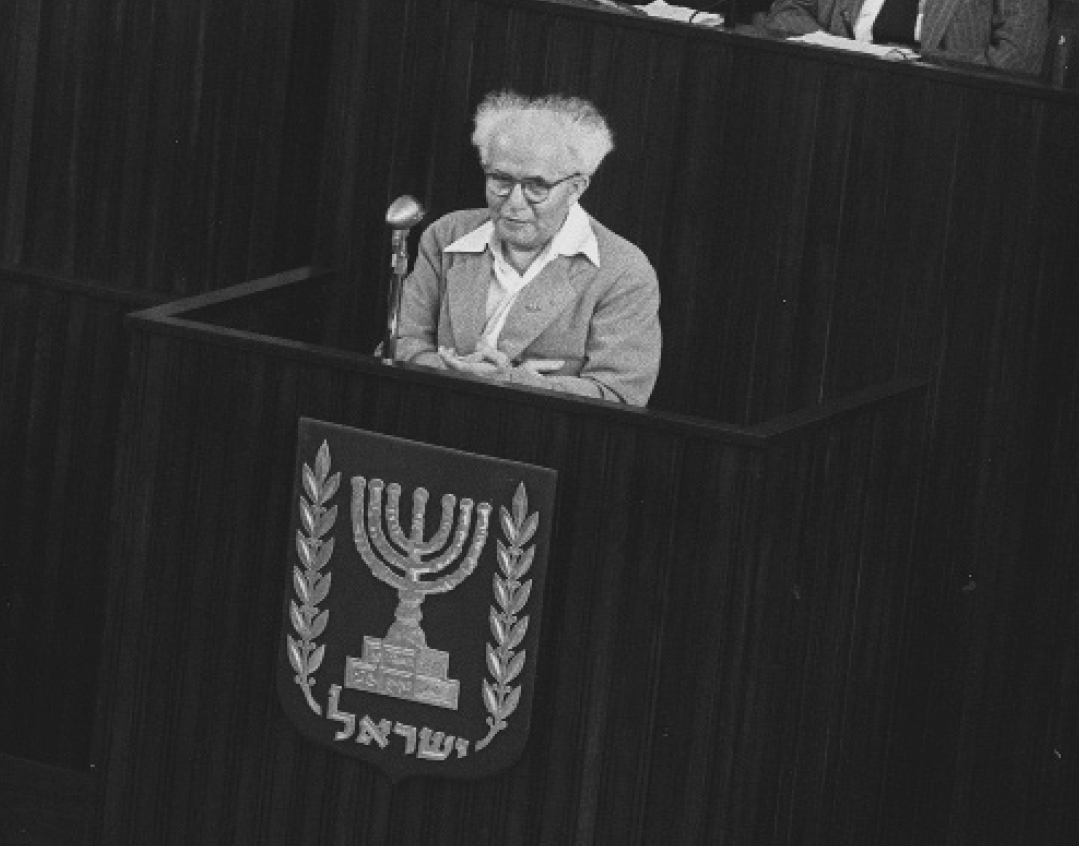

The death of Israel’s Labor Party has been at least a decade in the making, so long that even its veteran activists aren’t surprised by the party’s demise. The party, which in its first incarnation as the Mapai ruled the country from 1948 until the Likud upset victory of 1977, gradually lost its hold on the Israeli public over a process of three decades, the end of which came last month.

After winning 44 seats in 1992, Labor was never again able to reach those heights. It continued its progressive decline after the 1995 assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, with 34 seats in 1996, 26 in 1999, and 19 in 2003.

There are a number of reasons for the party’s decline. The 1996 elections saw direct elections for prime minister, with a separate ballot for party lists. That arrangement allowed voters to choose smaller parties while still having a say on the one-on-one contest for prime minister between Likud’s Binyamin Netanyahu and Labor’s Shimon Peres. After that, the decline became a purely ideological matter. Labor leader Ehud Barak, elected in 1999, failed to advance a peace process at Camp David, and then had to battle the Second Intifada. The agenda in Israel shifted from peace to security. And Labor, despite its tradition of running generals such as Yitzhak Rabin, Ehud Barak, Amram Mitzna, and Binyamin Ben-Eliezer, failed to convince the public that it would do a better job of providing security for the country.

In 2006, Amir Peretz steered the party in the direction of economic and social egalitarianism, talking more about the minimum wage and social justice than the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But the Israeli public, scarred by the Second Intifada, preferred a party of government and chose Ehud Olmert’s Kadima. From then on, Labor became a niche party.

Throughout this period the party suffered from endless internal squabbles, going through eight leaders in ten years. In addition, the party failed to offer a serious governing alternative, time and again choosing to enter right-wing governments and receive comfy ministerial posts rather than championing its principles from the opposition. Binyamin Ben-Eliezer joined a unity government with Likud’s Ariel Sharon during the Second Intifada; Amir Peretz joined Olmert’s government in 2006; and Ehud Barak joined Netanyahu’s right-wing government in 2009. Voters realized that no matter what was promised to them before the elections, Labor would bolt to the other side as soon as polls closed. Many party activists rightly viewed this strategy as the best way to become a fifth wheel, not a governing alternative.

The process was briefly reversed in 2015, when Yitzhak Herzog joined up with Tzipi Livni to win 24 seats, a result that returned color to the cheeks of many party veterans. For a short while it appeared that the party had returned from the dead. But even the alliance with Livni couldn’t take the party further than second place, and the alliance broke up ahead of the 2019 elections.

It was then that Labor attempted to shake off its historical image as the party of the Ashkenazic elite, electing Avi Gabbay, a Mizrachi businessman who had been one of the founders of Kulanu, as chairman. In response, the Ashkenazic voting bloc deserted the party en masse in favor of Benny Gantz’s Blue and White, and Gabbay’s Labor (in Israel’s April 2019 elections) was reduced to a historic nadir of six seats. Gabbay was forced to resign by enraged party members, to be replaced by another Mizrachi, Amir Peretz, who forged an alliance with Orly Levy-Abekasis, yet another Mizrachi woman who claimed to represent the “periphery.” But the pair received the same pitiful result of six seats in Israel’s second recent election, in September 2019.

To avoid a total wipeout in March 2020, Peretz and Levy united with Meretz, a leftist party. Together, the parties won just seven seats, meaning that if Labor had run on its own, it might not have crossed the electoral threshold.

Over the last year, as Israel has endured three electoral campaigns, Labor Party leader Peretz promised again and again that he would never sit with an indicted prime minister, namely Binyamin Netanyahu. To put public skepticism to rest, Peretz released a campaign video in which he shaved off his trademark mustache. He explained to the voting public that this act of barbering would allow voters to more clearly read his lips when he proclaimed, once again, the he would never sit with Netanyahu in a coalition government.

After the March 2 election, the mustache was gone, but the man remained. Peretz hurried to join the coalition as soon as Netanyahu and Gantz signed their unity agreement. It appears that the remaining party activists were relieved by this development. It’s difficult to see how a party with three MKs could once again rise to an opposition ruling alternative, much less a majority party.

“What sealed its doom was its willingness to join any right-wing government no matter what, and its pandering to a certain demographic that would never actually vote for it, alongside self-destructive internal mechanisms, which denied party chairmen enough time to put forward innovative, popular ideas,” Daniel Herosh, a former Labor Party spokesman and an advisor to former chairman Yitzhak Herzog, said.

The party became only interested in itself, Herosh opined, in its internal power struggles, and in providing jobs for political wheeler-dealers. “The big absurdity is that Labor’s actual positions enjoy majority support among the Israeli public: yes to the two-state solution, yes to social justice and a strong welfare state,” he said. “The trouble was with those who carried the message, and not with the message itself.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 809)

Oops! We could not locate your form.