Partisan Rabbi

Meah Shearim native Rabbi Hillel Cohen is braving danger at the front lines and borders to rescue stranded Jews

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, AP Images, Personal archives

Artillery rumbled, drones flew overhead, and in the small towns west of besieged Kyiv, infantry fought at close range as an unusual ambulance set out for the front line a few days after Purim.

Inside was a Meah Shearim–born chassid in a Hatzalah jacket called Rabbi Hillel Cohen, along with Alexander Borisov, a businessman and Ukrainian army veteran turned volunteer driver.

As they left the roadblocks defending the capital behind them and headed into the thickly wooded countryside, the scenes they took in were apocalyptic.

Homes and supermarkets reduced to blackened hulks; the bridge at Irpin leveled; Hostomel Airport — scene of a savage battle between Russian paratroopers and Ukrainian forces — utterly destroyed.

But as the ambulance approached the town of Vorzel, which was still partially occupied by Russian forces, their tension mounted. In the house-to-house fighting there, the Russians had been pushed back a few streets. Burnt trucks and tanks were evidence of the slaughter that had taken place. Bodies lined the streets, and the living were desperate for water. Ukrainian soldiers, the pair knew, wouldn’t shoot, but the Russians targeted ambulances regularly.

Within 15 minutes, the job was done. The ambulance swooped in to load its precious cargo — a Jewish mother, daughter, and two grandchildren who were cowering in a basement — and raced out, hightailing it for Kyiv.

Even two weeks later, Hillel Cohen is shaken as he remembers that episode — and that’s saying a lot, because since the Ukraine war began, almost nothing has deterred this man in his quest to rescue the Jews of his adopted country.

For almost 25 years, Hillel has been a human tornado of Jewish activity in Ukraine. With no official rabbinic position, he’s married off couples, arranged more than 1,000 brissim for grown men, built mikvaos, and run a chassidic-inspired outreach program called “Baal Shem Tov’s Kinder.”

But this war has turned this father of eight and grandfather of two into something else.

“Partisan” is what people have started to call him.

In the span of a few weeks, he’s racked up almost 5,000 miles across the war zone, shuttling old people, babies, mothers and dual citizens out of the firing line, first in minivans and now by ambulance. The distance itself pales in comparison with the sheer chutzpah, resourcefulness, and fearlessness demanded by this epic journey.

“I call him Rav Rambo Cohen,” says ambulance driver Alexander Borisov. “There’s nothing he can’t do.”

Singing and dancing his way across Ukraine to endless iterations of Modeh Ani, and stopping to break the ice for predawn tevilah, Hillel Cohen has brought chassidic spirit to the holy business of saving Jews.

BRIDGE TO NOWHERE Two starving Jews were plucked from Irpin, surrounded by Russians

No Jew Left Behind

Like most Ukrainians, Hillel Cohen didn’t believe that Vladimir Putin would make good on his threats to conquer his neighbor, but as a precaution, the rest of the Cohen family was safely in Israel when the invasion began.

That’s how it was that the Jerusalem-born chassid with the “Mey-oh Shorim” accent found himself alone in Ukraine as it was bombarded on February 24, the day the war began.

Intending to go a wedding in Odessa, he took the train from Kyiv to the city on the Black Sea coast, with no supplies for a long stay.

But as news of the attack poured in, plans changed. It seemed the only prudent thing to do was get out, and fast. A large convoy would be leaving Odessa carrying the Tikvah community of Rabbis Refoel Kruskal and Baksht before Shabbos, and Hillel reserved a spot.

But then, early on Friday morning, things went wrong.

“You have ten minutes to get here, otherwise you’ll miss the bus,” the convoy operators told him.

Thrown by the suddenness of it, Cohen, who was staying some distance away, replied, “How can you give me just ten minutes? It takes longer than that to get to you!”

In the panic of the exit attempt, there had been a mix-up. There was no way Hillel Cohen could get there in time — just as there was no way the human caravan could afford to wait.

Cohen knew Odessa well, having been instrumental in building a mikveh there, and so he decided to stay for Shabbos while researching his options.

Leaving it all behind wasn’t so simple. Activism and Ukraine had gone hand-in-hand for decades for this Yerushalmi.

He was seven years old when he flew from Israel to visit Uman along with his father. Then on a return visit to the town in 1993 — long before the vast crowds arrived — he befriended a group of local non-Jewish boys his age, learning to speak Russian and navigate the region. By 1999, Hillel had moved to the country to begin his activist career.

By the time Putin’s divisions rolled over the border, Hillel Cohen had become a local legend, a fixer par excellence, with an endless appetite for helping others. As boss of the local branch of Hatzalah, which dealt with tens of thousands over Rosh Hashanah, he would regularly have to switch from tefillah to emergency mode as he airlifted a patient out to a local hospital with the helicopter he kept on hand.

So over Shabbos in the main shul of Odessa — strangely empty, save for a few dozen Jews left behind — Hillel Cohen came to a decision. He was going to stay and help others.

“If Hashem has made me a partisan, I need to carry on”

Border Control

The first call to arms came within days from an Israeli who had fallen sick in Uman. The local hospital wanted to amputate his foot, and Hillel knew that he had to get the man out to Israel for proper medical care.

“It was very difficult, but I managed to get an ambulance to take him to Odessa, where he was stabilized in the hospital. By Monday — four days after the war broke out — I arranged an ambulance to take him to the border. Also with us was a 90-year-old savta, plus a boy who had been left behind in Dnipro when his mother had fled, mistakenly taking her son’s passport along.

“Without documents he couldn’t leave, so as we approached the border, I put a pile of clothes and bags over him, and the guard waved us through.”

It was the first experience of something that would become a modus operandi.

Thus began a whirlwind of rescue efforts, involving intricate, constantly changing coordination from his trusty phone, and vast sums of money to pay drivers and people-smugglers.

“In those first days, there was chaos. Families were split up, men who were three months short of 60 and in ill health were drafted. There were Israelis who held Ukrainian passports and were trapped.”

Working the phones from Odessa was one thing, but the next level was helping people escape from Kyiv. Before he went back to the war-torn capital for the first time, Hillel Cohen wanted to know that he was going to be safe.

“I sent a message to Rav Chaim’s grandson, Yanky Kanievsky, and the gadol assured me that I was considered a sheliach mitzvah.”

With that brachah under his belt, Hillel headed east as everyone else was going west.

One day, he got a call from a former student, David. The boy and his mother Chana lived in Irpin, 20 kilometers from Kyiv. The town became famous as Ukrainian forces detonated a major bridge over a river to check the advance of Russian tanks who would have to pass that way en route to Kyiv.

“Can you rescue us?” asked David. “We’re totally surrounded by Russians. We’re in our basement preparing Molotov cocktails.”

When Hillel Cohen got through arrived in the Irpin basement, he discovered that the student and his mother had almost starved. “They’d had a couple of crackers a day for ten days.”

For those above draft age who couldn’t leave via the frontiers, the only way was the back door.

“Ukraine has many borders, and in every frontier town there are smugglers. They run cigarettes and people — they always have and always will.”

Quick with a story, Hillel points out the abundant meshalim involving smugglers.

“Remember the one about the smugglers who were disguised as a burial party? The border guards got suspicious that they weren’t weeping, and when they opened the coffin and found the illicit goods, the smugglers began to cry.

“‘Aha!’ exclaimed the guards, ‘you should have cried before and you wouldn’t be crying now.’ ”

Getting back to his narrative, Hillel Cohen makes light of the danger involved. “There are places where the people crossing were fired on, or where the group had to wade through rivers to cross the border. Once our van got stuck in the mud a short distance away from a guard post. When we got out of that one, we started to sing ‘Am Yisrael Chai.’ ”

Two students of Hillel Cohen’s in the Ukrainian army

Bluff Tactics

Hillel Cohen found that the most important thing in his new line of “work” was utter self-confidence.

“There was a mother who had become separated from her baby — the baby was in a Kyiv hospital and she was in western Ukraine,” he remembers. “I had no way of getting the baby across Ukraine, but I asked a leading Jewish doctor to go and sign release papers and then hand the baby over to a driver who would be waiting.

“Of course, there was no driver,” continues Hillel, “so when the doctor had the baby outside the hospital demanding to know where the driver was, I told him, he’s delayed — take the baby home and buy some baby formula.”

By then, the doctor was livid, but complied. Meanwhile, Cohen was working the phones and found that there was someone leaving Kyiv for western Ukraine. The driver was persuaded to take the baby for a short distance, where another — as yet imaginary — driver would pick the baby up.

More phone work located a couple who were prepared to take the baby to safety. A few hours later, the infant found itself back in its mother’s arms, and the intrepid rescuer had learned another lesson: Never underestimate the power of short-term thinking.

Those tactics made Cohen and a team of contacts on both sides of the border a rescue road show as he crisscrossed Ukraine to deliver help wherever needed.

On one journey, captured by a cameraman for Israel’s Channel 13 network, he stops in Zamerizhka, a small town, to visit Natalya, an old lady who was running out of supplies. Unloading sugar and basics, he calls her worried daughter in Israel, and the three talk.

In another town, Svetlana, a mother of three, describes the massive jump in costs of basic goods. Her teenaged son is introduced by Hillel to the delights of Bamba, and the younger children receive Purim coloring books.

Bringing warmth and comfort to a Jew left behind

Shabbos Rescue

While Hillel Cohen has gone out of his way to help any Jew in trouble, several cases feel like the closing of a large circle.

“There’s a couple — Yaakov Veksler and his wife from Kyiv — whom I married off. They live in Boro Park now, and Yaakov’s mother and grandmother, who is 90, could never go to the US to visit. So they didn’t even see Yaakov’s children.

“Then when the war broke out, they were torn about leaving their homes and said to me, ‘We’ll only leave if you help us get all the way to America.’ ”

With no idea how he was even going to get them out, Hillel Cohen gave them his word.

He managed to get them out of Kyiv after Friday night kiddush (Hillel’s received halachic guidance on traveling on Shabbos if it can facilitate saving lives). In parallel, another drama was unfolding in Odessa.

A family left in the city had what would in normal times be a simchah. But besides the shelling in the background, the birth of a baby boy created the difficulty of finding a mohel.

Virtually all the city’s Jews had fled, and no mohel could be persuaded to head back into the battered country. So, Hillel Cohen persuaded his brother, Reb Naftali, another adventurous soul who lives in Beit Shemesh, to get on a plane.

Naftali left behind his own wife, who’d given birth two weeks before, and immediately ran into trouble. At the Moldova-Ukraine border, suspicious guards detained him after finding a white powder in his case. It was a medicine used to treat the milah wound, but in the wartime atmosphere, no one was taking chances.

“I spent hours on the phone with my brother, and nothing helped. In the end, he shouted at the border guards, ‘Eliyahu Hanavi! Eliyahu Hanavi!’ and for some reason they let him go.”

While that was unfolding, Hillel’s group arrived in Uman, a three-hour drive to the south. There Hillel, an accomplished baal korei, read Parshas Zachor, and then they continued on to Odessa, arriving in time for Seudah Shlishis.

There, Hillel met his brother, who had meanwhile performed the bris, and was eating a meager Shabbos meal with two men in the empty shul.

After Shabbos, the happy parents approached Hillel again and asked for help crossing the border to Romania. Hillel told them that passage meant the husband hiding at the bottom of the vehicle. At that point the husband got nervous and asked to reconsider things. By the time he’d made up his mind, the ambulance was already over the border in Romania, and Hillel told the couple to wait until Purim, when he would come back to Odessa from Kyiv.

As promised, the tireless rescuer was back in Odessa for Purim to read the Megillah for the 30 remaining Jews, and to carry on his shuttle mission.

To avoid the curfews, which can see people shot for being outside after hours, the Megillah had to be read early. Then Hillel intended to leave the city with the young family.

But before they left, an old man said, “Where are you going?! We need you to read for us tomorrow!”

Departure was put off until the next day. “It was very sad — tragic, really. There were 15 people left in a shul that had held 1,500 the previous year. We ate a seudah of fish in the shul, danced, and then left for the border.

“As we approached the border, I covered the husband with clothes and took out all the medicines that we had in the ambulance, piling them all over him.”

Partner in Rescue

Three weeks into the war, a match made in heaven brought Alexander Borisov and his ambulance to Hillel Cohen, and the operation stepped up a gear.

Alexander — or Sasha — is a well-to-do businessman who works in construction, real estate, and travel. His apartment in an upscale part of the capital displays his military past. Having fought Russian separatists in the country’s Donbas region between 2014 and 2016, he keeps his Kalashnikov at home.

But when he and Hillel met in Mezhibuzh, Borisov was driving an ambulance to evacuate a Jewish patient.

Their first meeting was typical of Cohen’s ebullient approach to life. As a Kohein, he couldn’t go into the Baal Shem Tov’s tziyun, so he was sitting outside and saying Tehillim.

“I saw him go past, and invited him to put on tefillin. He told me it was only the second time he’d ever done it, and then I took him to the frozen mikveh of the Baal Shem Tov.”

After drying off, Hillel Cohen did what he does best: He began to dance, singing “Shelo Asani Goy” and his own personal anthem, “Modeh Ani.”

A friendship was born, one that has deepened after weeks of shared dangers.

“I volunteered because the most important thing is to save Jews,” explains Alexander. “Is there danger? It’s definitely harder not to have a weapon to defend yourself, but my friends are off fighting.

“And besides,” he says with a grin, “the most dangerous thing is when Hillel catches me having a yogurt too soon after eating meat.”

That lighthearted embrace of peril is what has drawn this unlikely pair together.

“I’ve never met a religious guy like this,” says the ex-soldier. “He is ready to go into any danger. He can talk and negotiate and survives on no sleep. I should tell Elon Musk about Rav Hillel — he has the energy of ten people. Maybe he has special tefillin that give him the strength?”

Having sent his wife and children out of harm’s way to Italy, Borisov has spent the last three weeks at Hillel Cohen’s service. In a testament to his new boss’s way of touching hearts, he says that the last few weeks have been the most meaningful of his life.

“Everywhere that we are in trouble, we sing ‘Modeh Ani.’ He’s always singing and dancing. When we’re approaching checkpoints — which are easier to pass, because I hold a military ID — or going through the forest, we smile and joke and it helps relieve the pressure.”

As an army veteran, Borisov is confident that his fellow soldiers — including many Jews and Israeli passport holders on the front lines — have what it takes to defeat the giant Russian army.

“If our allies in Eastern Europe and the West don’t want to have battles like this on their own territory, then just give us good air defense systems so that we can close our airspace.

“Russia is a big country, but they have failed to take Kyiv, and will fail to take the Donbas in the east as well. If we don’t get weapons, we will win anyway, but there will be far more blood.”

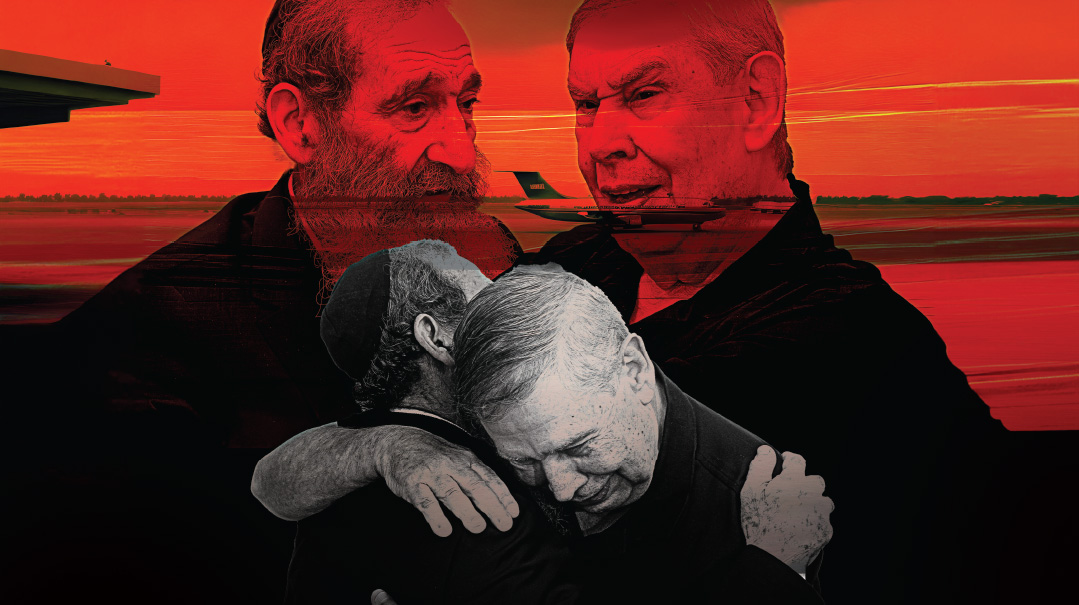

PARTNERS-IN-RESCUE Hillel Cohen with Alexander Borisov (above), and (below) his brother Naftali Cohen arriving to do a milah in Odessa when no one else dared

“What I Need, I Get”

Alexander Borisov’s arrival is only one of the strokes of Divine hashgachah that Hillel Cohen has witnessed since he took to the road.

“Particularly with money you see special things,” he says. “Taxi journeys of a couple hours can now cost $1,000. Smugglers can charge $8,000 to $10,000 per head. Different groups and people help, but I need large sums. I don’t know where I’ll get the money, but what I need, I receive.”

One recent day, he needed $300,000 immediately for operations. Where is money like that available in a war zone?

“It turns out that people who fled in a hurry left behind large sums, and they need a way to get it out,” he says. “So out of the blue, I received a phone call from someone. ‘I’ve left $300,000 in Kyiv — can you bring it across the border for me?’ ”

Another clear sign of Heavenly help came via a sefer Torah. Hillel — whose connection to the Baal Shem Tov and his great-grandson Rebbe Nachman of Breslov began in Meah Shearim and continued at the Baal Shem’s birthplace in Mezhibuzh — begins with the story of the “wondrous sefer Torah.”

Back in 1752, an epidemic spread around Mezhibuzh, killing many Jews. The Baal Shem said that to stop the plague, the community should join together to write a sefer Torah.

That undertaking, which stopped the death in its tracks, inspired Hillel himself to write a sefer Torah, after he recovered from a severe bout of Covid. A year ago, during Nissan 2021, Hillel’s new sefer Torah was dedicated to the Baal Shem Tov’s shul in Mezhibuzh, where it stayed until the outbreak of war.

“When the fighting began, I decided to rescue my sefer Torah as well as others that were in Uman,” he says. “I brought it to Israel, where we had a very joyous hachnassas sefer Torah at the site of Dovid Hamelech’s kever on Har Tzion in Yerushalayim.”

While the festivities were in full swing, Hillel’s phone rang. On the line was a friend: Rabbi Refael Katz of Heichal Baal Shem Tov, a shul in the city’s Ramot neighborhood. Rabbi Katz had an unbelievable request.

“Just last night, the donor of our only sefer Torah asked for it back, and then we heard that yours just arrived. From the Baal Shem Tov’s shul to Heichal Baal Shem Tov — can we have the sefer Torah?”

RICHES TO RAGS Former millionaires come to stock up on basics in Nachman Cohen’s refugee “store”

Endgame

With his family all in Israel, Hillel Cohen has come for two days before Pesach to see them and plot his next moves.

Having grown up in Ukraine, learned in Gateshead, and studied in Hillel Cohen’s academy for activists, his children are high achievers in their own right.

“My children grew up as shelichim,” he says.

Nachman — married and living in Beitar — has set up a “store” for refugees in the capital’s Givat Mordechai neighborhood.

It occupies an off-duty children’s kindergarten. Inside, everything from clothes to kitchen essentials, food, baby formula, cribs, and strollers stand in neat order. It’s all new, donated by stores all over the country, and refugees can come and take what they need.

Some of the “customers,” Nachman explains, were wealthy to the tune of millions back in Kyiv.

After hours now, the store is mostly empty except for David, whom I recognize. Last I saw him on a video clip, he was unfolding himself from a minibus in Romania after being rescued by Operation Hillel after war broke out. David exits with a bag load of basics.

“I’d like to set up two more stores like this — one in Haifa, and one in Be’er Sheva,” says Hillel, while eating a jar of Gerber baby food that turns out to be his only sustenance so far in another adrenaline-stoked afternoon.

Ukraine’s tragedy unfolds on a file that’s on Nachman’s phone. It contains dozens of names and numbers — mostly rabbis and community activists. Their homes and businesses are gone, and along with the communities, so is their leadership.

But as others look to Israel to rebuild their lives in whatever way they can, Hillel Cohen is heading back to Ukraine again.

He’ll link up with Alexander Borisov, and the ambulance that has become his field command office in his own personal war to save Ukraine’s Jews.

He plans to gather the hundreds of people who can’t exit the country and make one or two giant Pesach Sedorim for them.

Beyond that, he doesn’t know what the future holds. He’s a pioneer, a frontiersman, and can’t see himself ever living happily in the domesticity of Beitar.

So, as he lives through a period of adrenaline-fueled survival, where every kilometer traveled means helping another Jew, this larger-than-life character feels that he can’t step away.

“If Hashem has made me a partisan,” he says, “I have to carry on.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 907)

Oops! We could not locate your form.