Out of the Spotlight

| April 11, 2022Before London, Rav Chanoch Dov Padwa ztz"l spent 15 little-known years in Eretz Yisrael

Photos: Mike Poloway, Mishpacha archives

Say the name “Padwa” and most people envision England — the association between the family and the country is that strong. Preeminent posek Rav Chanoch Dov (Henoch) Padwa ztz”l left an indelible mark on London during his four-plus decades leading the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations before his passing in 2000. But while his name is most readily associated with the British institutions he led and the Kedassia hechsher he presided over, his rabbinical career began earlier, first in prewar Vienna, and then for another 15 years in Yerushalayim.

We’re sitting in Rabbi Shea Heshel Padwa’s modest, seforim-lined dining room in Manchester, but he soon brings us into another world. As a child growing up in Yerushalayim, he attended the legendary Eitz Chaim, where Rav Aryeh Levin was one of the mashgichim, participated in Rav Amram Blau’s youth movement in Meah Shearim, joined the informal Shalosh Seudos gatherings at the Brisker Rav’s home, and visited the Chazon Ish as a prize for joining Yeshivas Hamasmidim. While over 65 years have passed since the family moved to England so Rav Padwa could assume leadership of the UOHC, his son can easily conjure up the memories.

Yerushalayim of the 1940s and ‘50s, when the Padwas lived there, was a different world, poor in materialism but rich in Torah. It was a city where Torah giants not only walked the streets, but invited curious teens inside their homes, willingly sharing their insights along with a spot at their Shabbos tables.

There, in Yerushalayim of old, in the shadows of poverty, personal tragedy, and war, Rav Henoch Padwa learned, raised a family, and grew into a talmid chacham who would provide Klal Yisrael with crystal clarity in so many halachic issues.

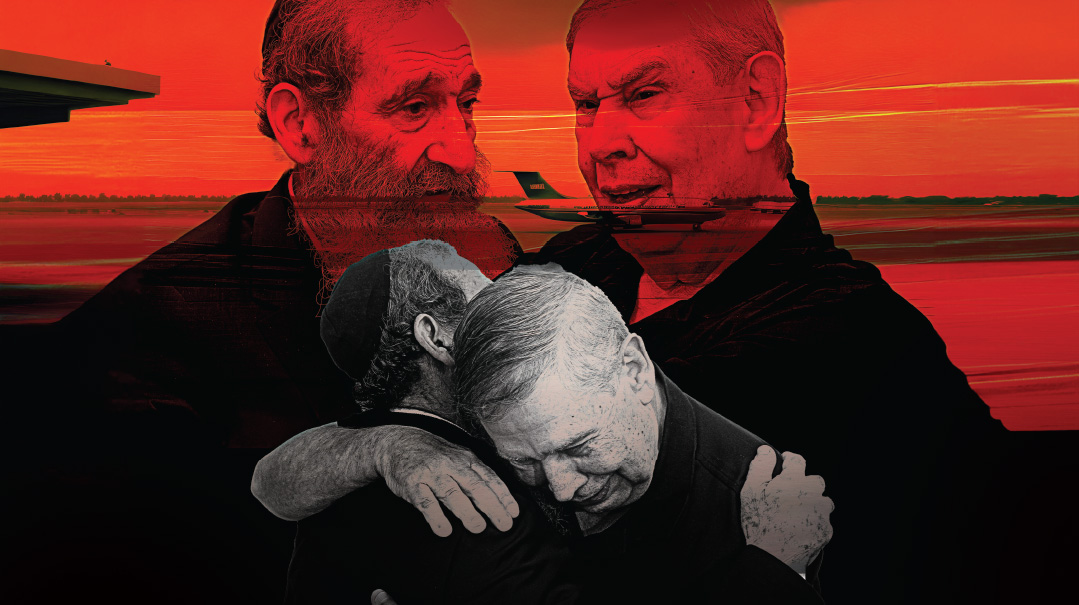

Rav Amram Blau might have been a zealot, but his youth movement was always fun and freilech (Photo: Efi Sharir Photography)

Meah Shearim — A World Apart

“I broke the mold, because everyone said you went into Eitz Chaim at age three and came out in a coffin.”

“This is my father’s passport, used for the escape from Vienna, Austria, on April 6th, 1940,” Rabbi Padwa says, showing us a small, worn, grey passport. Inside, there is a picture of his distinguished father, looking very young. There’s also a thick black line. “The black line on this ‘Juden Pass’ is a symbol that the bearer is a Jew, in case anybody might not notice,” he says.

Rabbi Shea Padwa was four years old when the family escaped Vienna for Eretz Yisrael. They traveled by rail to Trieste and left Europe on a boat to Palestine, arriving in Yerushalayim in 1940. The community was tiny, and the two popular chareidi neighborhoods were what was then called Machaneh Yehudah (today’s Nachlaot) and Meah Shearim.

“There was a shortage of rabbanim in Yerushalayim at the time. My father, who had already been a rav in Vienna, was offered a rabbinic position by Rav Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky, the Gavad of the Eidah Hachareidis. It was a small position in Machaneh Yehudah, not much of a commercial proposition, but better than nothing.”

Rav Henoch Padwa was a talmid and close associate of the famed Tepliker Ruv, Rav Shimshon Aharon Polansky (1876-1948), who is regarded as the mentor of the morei hora’ah of that generation, and his son believes that it’s possible the Tepliker recommended him to the Eidah Hachareidis when he arrived in Yerushalayim, in need of some sort of income.

The Machaneh Yehudah neighborhood back then consisted of two blocks of houses, Batei Broide and Batei Rand. Externally, they were almost identical, but each boasted its own shul and its own distinct, vibrant character — Batei Broide was Litvish, set aside for the Perushim community, and Batei Rand, chassidish.

Rav Henoch Padwa was rav of both communities, but he davened with the chassidim. “The litvishe had two minyanim,” his son reminisces, “the first at neitz and the later minyan at 7 a.m. The chassidim had an 8 a.m. minyan in addition, and that was considered very late. When I first moved to chutz l’Aretz and heard that some minyanim began at 9 a.m., I thought they were crazy.”

While the family escaped the Holocaust, tragedy followed them. When Rebbetzin Padwa was tragically niftar in Yerushalayim in 1944, the Rav was left with five young children, and they were temporarily split up. Rabbi Padwa, the second child, who was seven at the time, was sent to live with his maternal grandparents in Meah Shearim for a while. Although only about a 15-minute walk from Machaneh Yehudah, Meah Shearim was a world of its own.

“I found myself in the center of activity of the kanaim. There, Rav Amram Blau ztz”l had created a youth movement, called B’mesilah Naaleh. I had not a clue what it was all about, but I was a kid, of course I joined. All the kids went — it was freilech,” Rabbi Padwa says, showing us a tiny Tehillim that he received from Rav Blau’s movement.

While young Heshel Padwa had been learning in Yeshivas Eitz Chaim, for the two years that he was raised by his grandparents in Meah Shearim, he transferred to the local Torah V’yirah cheder. “I broke the mold, because everyone said you went into Eitz Chaim at age three and came out in a ‘kestel’ [coffin],” he jokes. Although the influence of the kanaim pervaded the atmosphere in Meah Shearim, Rabbi Padwa remembers that at that time, the big Meah Shearim shul was controlled by those ideologically identified with Rav Kook — “the Mizrachisten.”

Rabbi Padwa remembers attending the wedding of Rav Yaakov Meir Shechter, who married a niece of his father’s second rebbetzin.

“I went along for the chuppah. Weddings in those days took place on Friday and the seudahs were held on Friday night, only for close relatives and the poor, so most people could hold a wedding meal right at home with plenty of space for the limited attendees. If more space was needed, people held the seudah in the Ungarischer Talmud Torah.

“Another celebration took place on Motzaei Shabbos, when a Yerushalmi poiker [drummer] came along, and all the friends of the couple and the families came along to dance. That was the main event of the chasunah. And the kibbud? There was petel — or as we called it back then, roiter vasser, red water.”

Cheder finished at six o’clock, and later on in the evening, many boys attended a program called “Yeshivas Hamasmidim” for an hour of learning with seforim offered as prizes. “Yeshivas Hamasmidim took place in Ungarischer hoiser [Batei Ungarin] in Meah Shearim,” Rabbi Padwa remembers. “Once, on Chol Hamoed, Reb Moshe Mendel Winkler, one of the Torah geniuses of that era, took a few of us boys to Bnei Brak to see the Chazon Ish, as a treat. I was one of the group, together with my friend Rav Noach Heisler, now rav of Sanhedria Murchevet, and another two boys.

“We traveled from the Central Bus Station to Tel Aviv, then on to Bnei Brak. When we came in, there was a man in the room with a jet-black beard.”

“Who is that Yid?” I asked our guide.

“You don’t know? It’s the Chazon Ish’s brother-in-law, the Steipler.”

“Then, they told the Chazon Ish that there were four bochurim here from Yeshivas Hamasmidim. ‘If you are masmidim, why have you spent a day coming to Bnei Brak?’ he asked lightly. Then he inquired what we had learned, and we replied that it was Maseches Gittin. The Chazon Ish asked, ‘What happens if you write on the get, harei at mekudeshes li?’

“I tried to think what the Chazon Ish meant, what the deeper meaning was, while Noach Heisler next to me started to laugh. The Chazon Ish turned to him, ‘Gut, that’s the answer.’”

Rooted in Belz

“The fish was dancing in the bucket, and it sprayed the Ruv, who said lightly, ‘It’s a chassidishe fish, it dances.’”

Rav Henoch Padwa was close to many gedolim, but his closest connection —actually a family tie — was to the Belz dynasty. His first rebbetzin was a descendant of the Sar Shalom of Belz, daughter of Naftali Gottesman, who was Rebbe Aharon’s secretary. Rav Henoch himself was named after the Lev Sameach of Alesk, who was a son-in-law of the Sar Shalom. His father, Reb Leizer Wolf Padwa, who worked as a tailor, was a seven-year-old who remembered clearly the holy court of Reb Shea’le Belzer, the “Mitteler Ruv,” and was among the few who were still present in the postwar years to rebuild the Belz chassidus under Reb Aharon of Belz, the fourth Rebbe, then watch its renaissance under the current Rebbe.

Rav Padwa had met Rav Aharon of Belz in prewar Belz and was a lifelong chassid. When the Ruv came to Eretz Yisrael after his miraculous escape from the Nazis, Rav Henoch traveled up to Haifa to greet him.

“My father could not recognize the Ruv, who was shattered and broken, emaciated beyond belief. He had a terrible shock. Only when he saw someone give the Ruv his hand in the customary fashion was he sure this was the Ruv. That’s because the Ruv would only reach out his hand for a mitzvah, not for any other purpose, including greeting someone. So he would gesture to those who wished to give him their hand to lean closer and put their hand close to his.

“Reb Aharon used to send sh’eilos to the Tchebiner Ruv sometimes, and I know for a fact that he sent sh’eilos to my father too,” says Rabbi Padwa. In certain circumstances, Rav Padwa’s zemanim, known as “Rav Henoch’s zemanim,” were relied upon by the Belz community .

After Rav Padwa lost his wife, he remarried his second rebbetzin, a granddaughter of Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, who raised his young children to adulthood and accompanied him to lead the kehillah in London. Her mother was a widow, and she requested that her son-in-law Rav Henoch come in to her whenever he was on his way to the Belzer Ruv so that he could mention her name and requests.

“The story goes that one time, my father was rushing, and he didn’t stop in at his shvigger on the way, because he figured that he knew exactly what she would say, anyway — it was the same each time. He came to the Ruv and said ‘Der shvigger hut gebeiten mazkir zein — my mother-in-law asked me to mention her name…’ and this time the Ruv said ‘Your mother-in-law is a choshuve woman who brought up her children alone. I want to hear her words exactly.’ So my father had to admit that he hadn’t actually been in there…”

Rabbi Padwa’s maternal grandparents, who were related to the Belz dynasty, had the special honor of preparing some of the Shabbos food for the Ruv. “My grandmother, who was known within the Belz family as the ‘Viener kroivah’ — the relative from Vienna — used to bake the bulkelech weekly.

“My zeide would cook the Shabbos fish for the Ruv. The procedure was that first the live fish had to be taken to the Ruv for inspection, then my zeide took it home to cook. As a little boy, staying with my grandparents, it was my privilege to go along. I remember how one time the fish was dancing in the bucket, and it sprayed the Ruv, who said lightly, ‘It’s a chassidishe fish, it dances.’ ”

During a period when the Ruv was experiencing health issues with his eyes, he once asked little Shea Heshel to bless him with a speedy recovery. “I was embarrassed,” Rabbi Padwa remembers. “I was just a little boy, and there were other people there. When I told my grandmother about it, she said, ‘Don’t wait for kavod! If the Ruv asked you, go in and give a brachah.’ So the next week I did so, and the Ruv was pleased. Later it occurred to me that perhaps the Ruv made this request so as to encourage a young orphan and draw me close.”

We Didn’t Starve

“Under the house was a cellar that could act as a shelter during the shelling, and there were enough beds for the adults. I slept in the bathtub.”

The Padwas lived in Yerushalayim during 1948, when the city was besieged and battered by the cannons of the Arab Legion at close range. The Tchebiner Rav, who had arrived in Eretz Yisrael in 1944, lived in the relative safety of Rechov Ibn Shaprut 19 in Shaarei Chesed, while Rav Henoch, his close protégé, lived with his family in Machaneh Yehudah.

Rav Padwa visited the Tchebiner Rav daily to speak in learning, and soon they devised a plan: The Padwas would move into the Tchebiner Rav’s home until the danger of canon fire passed. “We lived there for a few weeks,” says Rabbi Padwa, recalling the unassuming warmth and friendliness shown by the great Tchebiner Rav. “Under the house was a cellar that could act as a shelter, and there were enough beds for the adults. I slept in the bathtub.”

Rabbi Padwa is matter-of-fact about the poverty they faced back then. “We didn’t go hungry, although obviously there was no fancy food. Of course, during the time Yerushalayim was under siege in 1948, there was less to eat. Bread was rationed, and I remember that at one point I heard people saying there was just one day’s supply of matzos left, after that we’d have biscuits, and after that, ‘min haShamayim yeracheim…’ Anyway, right after those rumors went around there was a two-week ceasefire, so the convoys with supplies could come in to the city again, and we were able to get food.”

Rav Padwa sent his sons to learn in Eitz Chaim, the legendary yeshivah system founded in 1908 to serve the community of Yerushalayim. “Really, Eitz Chaim is a subject of its own,” Rabbi Padwa says. “There were all sorts of children there. Until age 16, it was cheder, then yeshivah ketanah until the chasunah — don’t forget that most of the boys married between ages 18 and 20. Then, after marriage, they returned for yeshivah gedolah.

“The two mashgichim were Reb Elya Porush and Reb Aryeh Levin, whose role was to take care of the under-16s. The melamdim went to him when they had a problem, and he was very capable of sorting things out.”

Rav Aryeh Levin, that giant of the spirit who was the mashgiach of Eitz Chaim, a prison chaplain to the many prisoners of the British mandate authorities, visitor to the lepers, and father figure to downtrodden residents of old Yerushalayim, lived in Mishkenos, very close to Batei Rand.

Rabbi Padwa remembers him coming over to ask sh’eilos to his father. “Rav Aryeh was such a voileh mentsh, a special person. He originally davened in the Batei Broide shul, but he used to go speak to Rav Kook, and there was a kanoi in Batei Broide who physically accosted him, calling him a ‘Kooknik,’ so he stopped davening there.”

Reb Aryeh also had a small yeshivah and a kollel. He took care of all the Etzel and Lechi members who were jailed by the British, even condemned prisoners on Death Row. “Probably because of his association with these prisoners, I remember Menachem Begin visiting Mishkenos to talk to Reb Aryeh.”

Another towering personality whom Rabbi Padwa recalls was Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, who had come from Slutsk to serve as Rosh Yeshivah of Eitz Chaim in 1925. “He sat and learned in a small room with curtains, and seforim piled on the table. Rav Isser Zalman usually davened b’yechidus, but as a matter of interest, when he would come to the minyan on Monday and Thursdays, he came to daven with us, the chassidim, in Batei Rand, not in Batei Broide.”

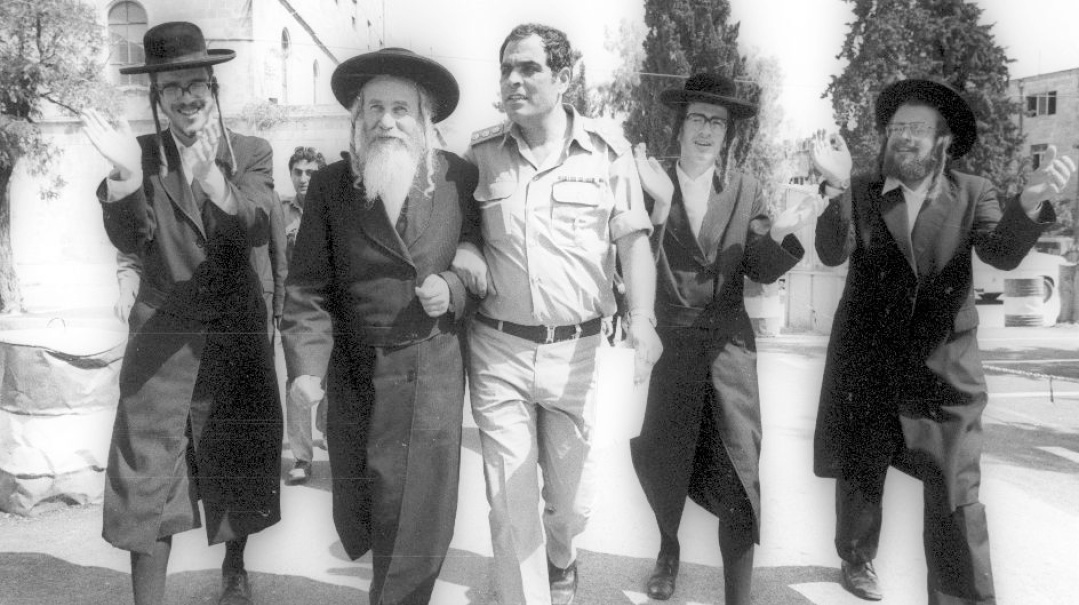

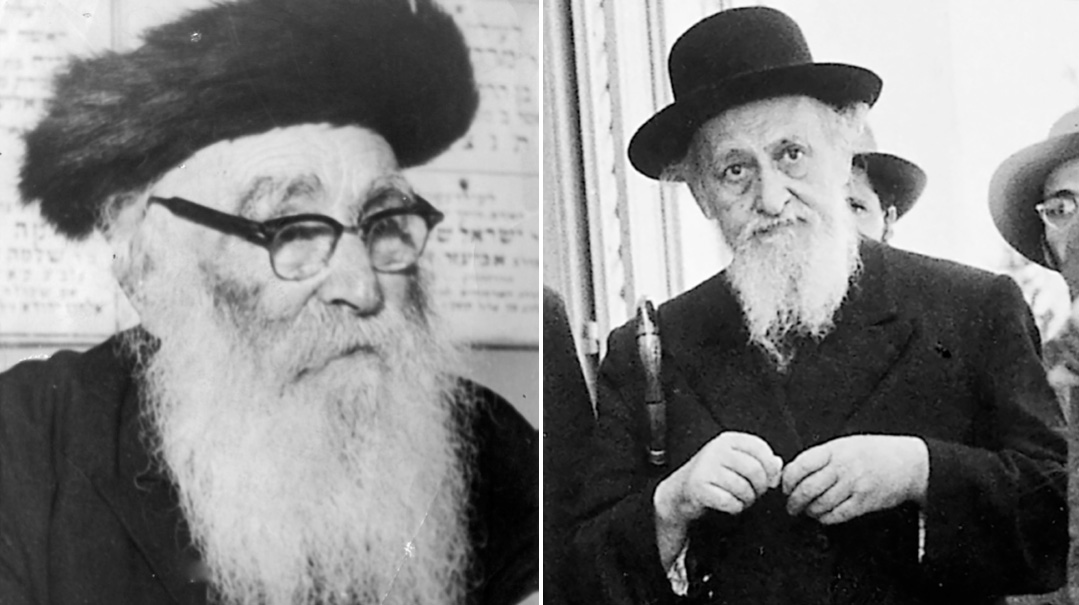

(R) “Rav Aryeh originally davened in Batei Broide, but he used to go speak to Rav Kook, and a kanoi accosted him, calling him a ‘Kooknik,’ so he stopped davening there

(L) The Brisker Rav didn’t use electricity on Shabbos, so when it got dark, people would come over and schmooze in learning

Land of the Giants

Living in Eretz Yisrael during that era meant easy access to some of the world’s great Torah giants. When the Tchebiner Rav opened his own yeshivah, he asked Rabbi Padwa, Rav Henoch’s son, to join. “I wasn’t really interested in moving to such a new yeshivah,” Rabbi Padwa recalls, “so the Rav offered me a chavrusashaft to encourage me to come.

“I left Eitz Chaim at that point and learned in the new Tchebiner yeshivah, and the Rav learned together with me each Friday after visiting the mikveh — we learned Maseches Makkos with Rashi and Tosafos, although the arrangement didn’t last too long.”

After a short time, Rabbi Padwa moved on to the Slabodka yeshivah in Bnei Brak, where he learned together with Rav Avrohom Dov Auerbach, the rav of Teveria. “All of Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach’s sons learned in Eitz Chaim, so I knew them from before, but I became close to Rav Avrohom Dov in Slabodka.”

The Chazon Ish’s presence was tangible throughout Bnei Brak, his influence shaping life in the city in every way, but access to the gadol was restricted by his faithful attendant, Reb Duvid Frankel. Rabbi Padwa found a time when the door was open, though.

“I knew that Reb Duvid occasionally went to the tish of the Imrei Chaim of Vizhnitz, so I used that opportunity to go into the Chazon Ish. He opened the door warmly, and then I needed something to say. I told him that I was finding a certain Tosafos difficult to understand, so the Chazon Ish took down a Gemara and learned it through with me, clarifying the pshat. ‘Vos is shver?’ he asked, and I replied that now I understood it.”

At the time the Padwas lived in Yerushalayim, Rav Chaim Naeh served as rav in the Bucharim neighborhood. His official job was Safra Dedayna (Registrar) of the Badatz Eidah Hachareidis, and Rav Padwa, who was a rav on the Eidah Hachareidis, had a close relationship with him.

The Beis Yisrael of Gur had a phenomenal memory for faces, years later remembering the young bochur who now had a full beard

“He was a gaon adir, a tremendous genius,” Rabbi Padwa recollects, “but he lived simply. They used to say that in Yerushalayim, he was known simply as ‘Reb Chaim Naeh,’ while in Bnei Brak, they called him ‘the Shiurei Torah,’ referring reverently to his sefer.”

In 1946, Rabbi Padwa, then a nine-year-old, went along with his father on Erev Yom Kippur, to get a brachah from the Imrei Emes of Gur. “The Imrei Emes was very broken after the war and he didn’t speak much at all, but he did give us a brachah that time.”

In later years, Rav Padwa would go into the Beis Yisrael of Gur on Erev Yom Kippur. “The Beis Yisrael had an incredible memory for faces,” Rabbi Padwa says. “I had gone into him as a bochur in Yerushalayim, and years later I went when I was visiting from England. I looked different, with a full beard, and he quipped, ‘Im chochmah ein kan, ziknah yesh kan — if he isn’t wise, at least he has signs of age (literally, a beard).’ ”

As Shabbos faded away in Yerushalayim, Rabbi Padwa remembers, a small crowd would gather at the home of the Brisker Rav, including Reb Nuchem Trokover (Partzovitz); the Charkover Rav, who had a kollel in Zichron Moshe; and lehavdil bein chayim lechayim Rav Moshe Sternbuch of the Eidah Hachareidis.

“The Rav didn’t make an official Shalosh Seudos. The weekly gathering happened simply because he didn’t use electricity on Shabbos, so he couldn’t learn when it got dark, and people would come over to sit and schmooze in learning.”

Rabbi Padwa also recalls some lighter moments he observed at the Brisker Rav’s table. “One of those lamdanim who came regularly used to repeat his own original Torah thoughts, and after almost every word, the Brisker Rav said, ‘Ich veis nisht — I don’t know.’ There was also a Russian doctor named Dr. Aronov, who liked to be present and hear the Torah talk.

“Once the Rav inquired whether there was a moon for Kiddush Levanah. This Dr. Aronov went out to check and came back eagerly reporting that there was ‘ah groiseh levunah, a big moon.’ The Rav smiled. ‘Ah groiseh levunah?’ he asked. ‘Then we can’t be mekadesh it.’ ”

Rabbi Padwa also remembers Rav Meir Soloveitchik, the Brisker Rav’s youngest son. “I knew him from Eitz Chaim and we used to talk. We had the same problem, because we were not younger kids and not old — that postwar group of she’eris hapleitah was not large. There weren’t many boys our age. When Rav Meir went into Rav Aharon of Belz, as a young boy, the Ruv didn’t follow his usual custom of wrapping his hand in a towel before the child under bar mitzvah took it, but let Meir take his hand. He said to him “You have a choshuve tatteh and a choshuve zeide, och, choh, hoh!”

Sign of the times. Rabbi Padwa still has the bar mitzvah gifts inscribed with brachos from Eidah Hachareidis head Rav Reuven Zelig Bengis (Middle) and Shaare Zedek founder Dr. Moshe Wallach (L). Rav Dushinsky (R) also deferred to his father

A New Frontier

“Leaving Yerushalayim and everything I’d ever known for the bleak landscape of England was a bit of a shock.”

Rabbi Padwa shows us some of his bar mitzvah presents, seforim inscribed with warm wishes by Rav Zelig Reuven Bengis (1864-1953), chief rabbi of the Eidah Hachareidis, and the Tchebiner Rav. The flyleaf of another sefer bears the signature of Dr. Moshe Wallach, founder and director of Shaare Zedek hospital.

Dr. Wallach’s connection to Rav Padwa, apparently, came about through the small herd of cows that the doctor kept in a small cowshed next to the hospital in order to ensure a supply of fresh milk for patients. Hilchos Bechoros dictate that a firstborn cow can’t be used for milking, but if it incurs a blemish, it no longer is in this separate category. It happened once that Dr. Wallach asked Rav Dushinsky to recommend a posek with the expertise to be “matir bechoros,” to rule on the exemption from firstborn status. Rav Dushinsky told him to speak to Rav Padwa for a ruling on this subject.

It was 1955, Rabbi Padwa recalls, when a delegation from London led by Rav Elchonon Halpern arrived in Yerushalayim to seek a rabbinic leader for the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations. The Tchebiner Rav recommended Rav Padwa, and the family moved to England.

It was a new frontier for Rav Padwa, under whose leadership London became a thriving center of Torah and chassidus, but for 18-year-old Shea Heshel, leaving Yerushalayim and everything he’d ever known for the bleak landscape of England was “a bit of a shock.”

While his father established a beis din in Stamford Hill and took charge of the gold-standard Kedassia hechsher, Shea Heshel went to the yeshivah in the small town of Letchworth, which had been a hub for chareidi Jewry during the war years when many fled the German Blitz on London.

“The Sassoon family, aristocratic Jews from the Far East, and some others had remained in Letchworth. They had a malchusdig home, where they had a minyan, and, Rabbi Sassoon being a talmid of Rav Dessler, there was a small yeshivah there. I became assistant rosh yeshivah, earning a fiver a week — not too bad for a bochur at the time.”

Rav Padwa never cut his ties to the rarified world of the Eidah Hachareidis in Yerushalayim. While in public, in London, he donned the traditional shtreimel and black beketshe, his golden caftan was worn at home on Shabbos for several years. Sh’eilos from Yerushalayim arrived steadily by mail, and every summer, the Padwas spent several weeks near the Rebbetzin’s family, not far from their old home in Machaneh Yehudah. There, the Rav would pasken on sh’eilos from colleagues and confer with his old contemporaries.

Rabbi Padwa looks down at the table, the seforim, the Tehillim, and passport, silent witnesses to history. His father’s gentle smile may be gone, but the world of Torah and halachah constructed in Vienna, Yerushalayim, and London is indestructible.

Even in far-away Stamford Hill, Rav Henoch Padwa never cut his ties to the rarified world of the Eidah Hachareidis

No Going Back

“My father and grandparents came from a tiny shtetl called Bisk, in Galicia. Mir zennen Galicianer,” Rabbi Padwa says. It’s a label that was proudly worn for generations, and Rav Henoch Padwa ztz”l was a quintessential Galician talmid chacham — razor-sharp and unpretentious.

During World War I, when the Russians invaded Galicia, the Padwa family, like hundreds of thousands of Jews in that region, picked up and fled. Since Galicia was a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the refugees did not need visas or travel documents to reach Vienna. While the refugees intended to remain in the relative safety of Vienna for the duration of the war, they often stayed much longer.

“The whole situation in Galicia changed as a result of World War I,” Rabbi Padwa explains. “Before that, the communities in the big cities dealt with the tzuris, the fallout from the Haskalah and Zionism, while in the small shtetlach, traditional Yiddishkeit was stronger. But World War I caused the Yidden to flee the shtetlach, and things never went back to how they were. Some of the shtetl communities were reduced to zero.

“My zeide told me that before World War I, the shtetl of Bisk where he lived had two shtiblach, but when he returned after spending the war years in Vienna, he found that the Alesker shtibel was closed, and the Belzer shtibel was tiny — it only had a minyan on Shabbos. So he couldn’t go back. There was no Jewish future back there. That is why the rebbes of Ruzhin, the Boyaner and the Tchortkover, did not return to Galicia after World War I. It was all over there.”

Growing up in Vienna, Rav Henoch spent most of his time learning. While a modern yeshivah framework was not part of mainstream Galician infrastructure, the budding talmid chacham spent his time on the benches of the shtibel, with a group of like-minded bochurim that included the future posek Rav Shmuel Wosner.

“They remained close in later years. Rav Wosner would visit my father when he came to Yerushalayim,” Rabbi Padwa says. “But interestingly, they diverged on psak and despite the mutual respect, didn’t have much common ground in psak.

“When my father was a little older, he wanted to go and learn in Tchebin, Galicia, which did have a yeshivah,” his son explains. “But when he arrived there, the Tchebiner Rav was away. So instead, he took a train to Cracow, and sat down to learn in the Belzer shtibel in Cracow.”

Vienna was the host city for several gedolim during the 1930s. “My father had connections to many of them: the Alshtdater Ruv, Rav Chaim Yitzchok Yerucham (d. 1943, father of the Alshteter Ruv of Boro Park), the Machzeh Avrohom (Rav Avrohom Mendel Steinberg previously Rav of Brod), and the Rebbes of Boyan, Husyatin, and Tchortkov,” says Rabbi Padwa.

The Padwas remained in Vienna until World War II came, “and it got freilech again.” They lived near a bridge in Vienna. One Friday night, as Rav Henoch Padwa made his way over the bridge to a tish, he was accosted by Nazi thugs who wanted to throw him into the river. A cyclist came and dispersed the thugs. Rabbi Padwa believes that the small beis medrash where his father was the rav was the first one in Vienna to be attacked by the Nazis. “Even before Kristallnacht, there were Molotov cocktails thrown through the windows,” he says.

The growing unrest prompted Rav Padwa to move to Eretz Yisrael. After 15 years living in Yerushalayim and serving as rav of Machaneh Yehudah, in 1955, a delegation from London led by Rav Elchonon Halpern arrived in Yerushalayim. They were seeking a rabbinic leader for the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations, which was founded in 1926 and serves as the umbrella organization of chareidi shuls in Stamford Hill, Golders Green, Hendon, and Edgware. With an extremely sharp mind and broad halachic shoulders, Rav Padwa was the recommendation of the Tchebiner Rav.

He did not disappoint his new congregation. Over his 40-plus years in the position, Rav Padwa raised the halachic standards of the organization and became renowned far beyond London as a decisive halachic address. His responsa are in print under the title Cheishev Ha’Efod. The strong halachic and kashrus infrastructure that he left behind remain a testimony to his scholarship, authority, and leadership.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 907)

Oops! We could not locate your form.