One-Two Punch

The first interview question was “What would you do if you’d walk into a jail cell and find an inmate hanging from the ceiling?”

F rom the youngest age I knew I was going to be a doctor.

I loved medicine I loved taking care of people and I loved discovering the intricacies of the human body.

My plan took a little detour however toward the end of my undergraduate studies when I got engaged to my husband Chanoch. Chanoch’s rebbi felt that it was not a good idea for me to be training as a doctor while starting a family and he recommended that I become a physician’s assistant instead.

Following his advice I went to PA school instead of medical school. It was a decision that would have huge ramifications later on.

Chanoch was learning in kollel when we got married so in order to support ourselves while I was in school we spent our weekends working as house parents at a Jewish home for mentally challenged adults. Chanoch also worked as a lifeguard in Williamsburg on Fridays. We took a cheap apartment in East Flatbush paying $85 a week in rent. (This was in 1980.)

My first PA job involved doing physicals at a government welfare office in Williamsburg but that position phased out after a short time. When I was looking for a new job I saw an ad posted by the infirmary of Rikers Island New York City’s main jail. They were looking to hire PAs and I thought working there would be a good way to amass medical experience.

The first question I was asked during my interview was “What would you do if you’d walk into a jail cell and find an inmate hanging from the ceiling?”

I calmly answered that I’d lift the inmate unwind the rope from his neck and begin resuscitation. I guess my answer satisfied them because I got the job.

I worked at Rikers Island for 14 years. My colleagues would joke that I went on maternity leave every nine months. But I worked until the very end of each pregnancy and returned to work after six weeks. I always worked the 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. “graveyard” shift so that I could be home with my children during the day. I’d sleep a few hours in the evening and then I’d leave the house for my shift at Rikers which was a half-hour drive away. In the middle of the night my husband would bring me the baby to nurse.

It was an unconventional arrangement — but we were hardly a conventional couple. Chanoch and I had both grown up in homes where one parent was not frum and the other parent tried valiantly but not always successfully to maintain religious observance. In the process of embracing full-fledged frumkeit we had both resolved to devote our lives to Torah come what may.

I also dreamed of having a large family, and indeed, I gave birth to 15 children. (We lost our third child to crib death at the age of three months, and, much later, we lost another child to cancer. I also suffered six miscarriages.) But Hashem blessed me with the stamina of a bull, and throughout my childbearing years I was able to be home with my kids during the day, hold down a full-time job at night, and run my house without any cleaning help.

Chanoch earned some money on the side by doing magic shows for kids. In his younger years, when he first took an interest in magic, he asked a gadol if he could do magic shows, and the gadol had said it was permissible as long as he explained to the audience that his tricks were really sleight of hand, not kishuf.

Between my salary and Chanoch’s side earnings, we covered our living expenses. We also made a point of paying full tuition for all our children; in our view, our kids’ schools were not charity-dispensing institutions.

As a young woman, I had studied at Neve Yerushalayim, and I felt strongly connected to Eretz Yisrael. Chanoch, on the other hand, had never been to Eretz Yisrael in his youth. The first time he visited Eretz Yisrael was when our 16-year-old daughter, our second child, presented him with a gift: a ticket to Eretz Yisrael, bought with money she saved up from babysitting.

A curious thing happened when Chanoch arrived in Eretz Yisrael for the first time. He kissed the ground — and instantly fell in love with the land. He decided, during that visit, that he never wanted to leave. He visited two leading gedolim in Eretz Yisrael — one born in Eretz Yisrael, one born in America — and asked if it was a good idea to move the family. Both encouraged him to do it. (A sister-in-law of the American-born gadol later told me that the psak Chanoch received from her brother-in-law was highly unusual; she had never heard of him giving similar advice to anyone else.)

When Chanoch shared with me his plan for moving to Eretz Yisrael, I was deeply conflicted. On one hand, I loved Eretz Yisrael and would have been delighted to live there. I also thought it would be good for the kids to grow up in the more insular environment of Eretz Yisrael, far away from the ubiquitous television, movies, and materialism of America. But on the other hand, I knew that transplanting the family into an unfamiliar culture and language would be a massive and risky undertaking. And how would we have parnassah? In Eretz Yisrael the concept of a PA did not exist. Nor did I speak the language, so my employment prospects were severely limited.

It wasn’t only I who was concerned. The rabbanim of our community thought Chanoch was exercising poor judgment in moving the family, and they called the two of us down to a hearing of beis din to express their apprehension and caution him against what they thought was a brash and impulsive decision.

One thing about Chanoch: He was for real. He had no bluster, no false piety, no delusions. Despite his difficult childhood — his parents divorced when he was two, and he grew up in abject poverty — he possessed legendary simchas hachayim and ahavas Yisrael. He always managed to put a positive spin on things and see the good in people. If the cashier in the grocery was nasty to him, he’d say he felt bad for her because she must have gotten yelled at that morning by someone. In his eyes, everyone else’s situation was somehow more difficult than ours, and he had a way of making the entire family feel that we were the luckiest people in the world.

When Chanoch spoke, his words came from the heart, and you couldn’t help but see that he really lived what he said. After questioning him, and me, at length, the beis din recognized that his decision to move to Eretz Yisrael was no passing whim, but rather a reflection of his profound commitment to Torah and avodas Hashem. Once they ascertained that I was ready to support him in this move, difficult as it would surely be, they gave us their blessing.

We moved to Eretz Yisrael in 1998, sleeping on mattresses on the floor in the beginning. “Just enjoy Eretz Yisrael,” I kept urging the kids. “Try not to focus on the difficulties.”

The hardest part of moving, for me, was unquestionably giving up working as a PA, which I loved. Initially, I took a job doing eldercare — bathing elderly patients, changing them, feeding them — for 22 shekels an hour (approximately $6). Chanoch could not bear the thought of my doing such hard labor for so little money, and after a while he insisted that I quit the job.

Who are among the highest paid workers in Eretz Yisrael? Cleaning people, of course. I, who had never hired anyone to clean my own house, worked for years cleaning houses for 50 shekels an hour. The work was unfulfilling, to say the least.

But I was willing to do whatever I had to do to support my family and enable my husband to learn. I worked as a baby nurse, spending nights at people’s homes caring for their newborns. I worked as a mother’s helper, caring for children so their mothers could go out to school or work. I worked at an offshore company that provides back-office services to companies abroad. In short, I did everything and anything, holding down three not-very-enjoyable jobs at a time and working practically 24/6.

Chanoch took charge of the home front, handling much of the childcare and housework while squeezing in as much Torah learning as possible. Had he not been such a serious masmid, utilizing every conceivable moment to learn, I could never have kept up the type of work schedule I did. It was his dedication to Torah, and his appreciation for my hard work, that fueled me to keep going.

When Chanoch’s rebbi saw the sacrifices I was making to support my family in Eretz Yisrael, he ruefully admitted that he regretted advising me to become a PA rather than a doctor, because I could have worked in Eretz Yisrael as a doctor. I had no compunctions about having followed his advice, though. We had listened to daas Torah — and I firmly believe that if you follow daas Torah, you don’t go wrong. If I encountered difficulties as a result of his advice, those difficulties were from Hashem, and were somehow for the best. I’ve never been one to dwell on “could have, should have” regrets. What was, had to be, and what is, is what Hashem wants.

That attitude carried me through the six-year illness and eventual passing of my ninth child, Leah, at the age of 12. And then it carried me through the biggest challenge of all.

Chanoch had thrived in Eretz Yisrael, learning safrus and shechitah and earning semichah. He was on his way to becoming a dayan when he fell ill. He was diagnosed half a year before the passing of my daughter, who became his “rebbi” in chemo. He suffered horribly for two years, and then, in 2014, he joined Leah in Gan Eden.

At that point, my lot seemed sorry indeed. I was a widow, a bereaved mother, a financially struggling immigrant raising a large family single-handedly. As long as Chanoch was alive, I had pushed through all the difficulties — but how was I supposed to do this on my own?

I knew that if I were to fall apart, my family would likewise collapse. Rather than sinking into despair, I chose to perpetuate my husband’s legacy.

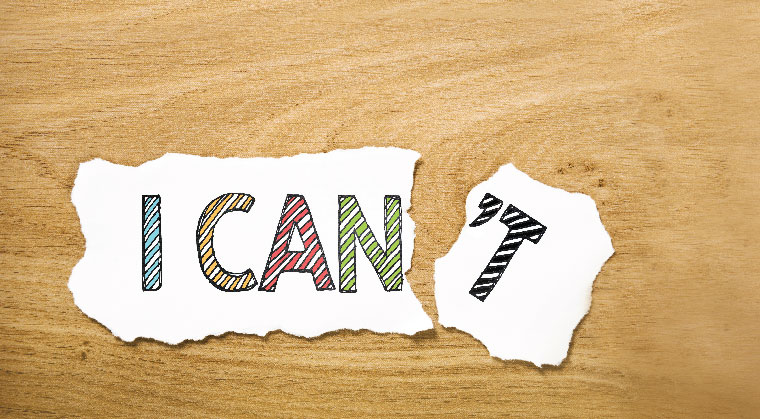

All the years, I had told my children that the word “can’t” doesn’t exist. It was a long-standing joke between us: they would say, “Ima, the word ‘can’t’ is in the dictionary, so it exists.”

I would insist, however, that the word does not exist. “If you want something badly enough,” I would tell the kids, “Hashem will help you get it.”

I had done many things in my life that other people would have said “can’t” be done. And I wasn’t about to stop now. I was down — but not out.

Chanoch and I had run an open house of sorts, hosting dozens of guests for Shabbos meals. I wasn’t about to give that up, even though Chanoch was gone and my financial situation was precarious. Nor was I prepared to give up taking the entire family on trips every Chol Hamoed, which was a cherished — but costly — family tradition. I continued to hold down three jobs, and somehow, Hashem always provided me with the money to cover these and our other expenses.

Prior to Chanoch’s passing, we had managed to marry off five children independently. In the three years since his petirah, I was zocheh to marry off another four children, with the help of generous friends in America.

If there is one thing I can say about my children — all of them — is that they are happy and well-adjusted. Like their father, whose example I try to follow, they take life in stride and don’t take their difficulties to heart.

People have compared my life to that of Iyov. But I don’t see it that way at all. Throughout everything I’ve been through, I’ve always felt that Hashem is with me and that everything He does is for my good. I don’t understand why things happen the way they do, but I’m not Hashem, and I don’t have to know the answers. When lemons come my way, I turn them into lemonade, making the best of each day and firmly believing that a better day is around the corner.

And you know what? I was right.

Just this year, Israel’s Ministry of Health decided to allow foreign-trained physician’s assistants to work in Israel, after undergoing additional training and internship. With the encouragement of my married children, who pledged to help support the family through my retraining period, I have enrolled in the first-ever PA program of its kind in Israel. I have three months of training to complete, followed by a year of internship, and then, for the first time, I will be able to work as a PA in this country.

It was as though Hashem led me into the Yam Suf right up to my neck — and then split the sea for me. I still feel the loss of Chanoch and Leah acutely, but the prospect of being able to earn a respectable parnassah while doing what I love to do is a tremendous comfort to me.

That’s not to say there are no more hurdles to face. My Hebrew is poor, and it’s scary to think of practicing medicine in a language I’m not comfortable in. It’s also frightening to give up my jobs and the income that comes along with them when I still have four unmarried children, as well as young married children who need my help.

I’m facing these hurdles with the same one-two punch I’ve used to face all the other hurdles in my life: ironclad bitachon and iron will.

As Chanoch would say, it’s going to be good. —

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 665)

Oops! We could not locate your form.