Kuf-Reish

| August 22, 2023Life is a cycle — and a spiral that pushes us higher

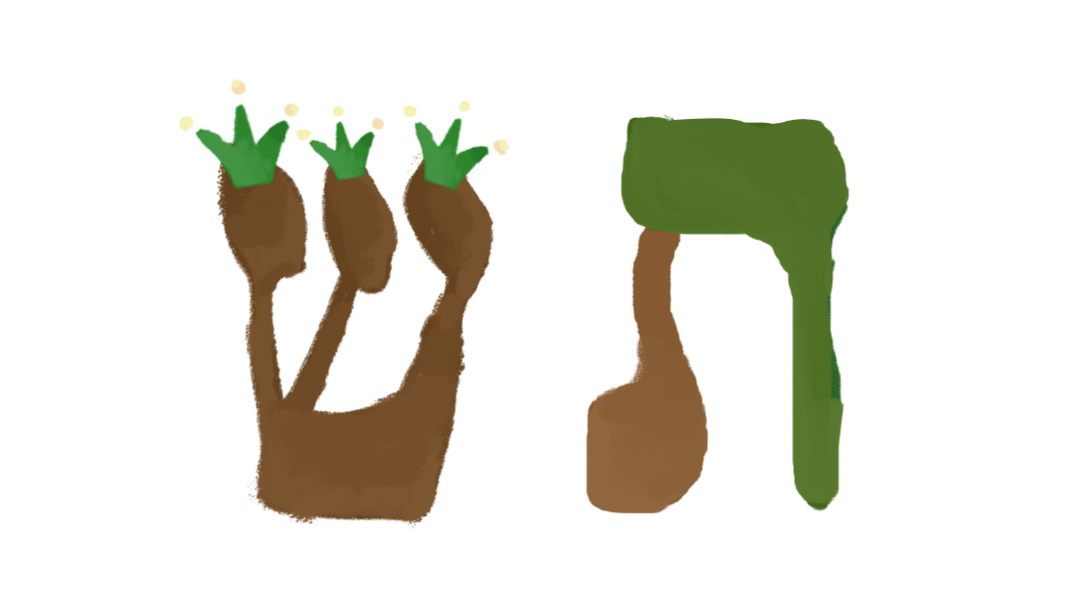

Kuf

Name: Hakafah (cycle) or kof (monkey)

Gematria: 100

Shape: A reish and a zayin

Middah: Kedushah

Kuf is the root of the word hakafah, cycle. The physical world is replete with cycles and processes: the rotation of the earth, the moon’s waxing and waning, the changing seasons, the daily sunrise and sunset. These “routines” show that there is an order to the world, which indicates an Orchestrator. It’s these cycles that alerted Avraham Avinu to the existence of a Creator (Rambam, Hilchos Avodah Zarah, 1:3).

The reality of a G-dly presence is what necessitates asking ourselves in any given situation: What do I need to do at this very moment? What is the best way to utilize where I am? Since the world is full of cycles — where do I find myself in the cycle? Is this a time for chesed? For discipline? For joy? For connection?

This is, in fact, the essence of kedushah — which the Gemara tells us is the concept behind kuf (Shabbos 104a). When an object is kadosh, it’s distinguished, set aside for a particular use. Shabbos is kedushah of time, the Beis Hamikdash is kedushah of place. We have the ability to make things kadosh — to determine how they can be used in connection to Hashem. We thank Hashem each day for the ability we have to distinguish when we say the brachah, “L’havchin bein yom u’vein lailah.” Things aren’t inherently good or bad; it’s how we utilize them. In this way, even the most seemingly mundane acts can be elevated. Judaism prescribes a way to talk, a way to cook, a way to use the restroom — all pointing us in the direction of kedushah.

In the time of Dovid Hamelech, there was a terrible epidemic. In response, Dovid Hamelech instituted the practice to say 100 brachos every day (Bamidbar Rabbah 18:21) to increase the people’s awareness of Hashem, to bring them back to the source of kedushah. Similar to the alef, with the gematria of one, which represents Hashem, kuf, gematria 100, is the letter representing the idea of finding Hashem everywhere.

As the 19th letter, kuf alludes to the consistent calendar cycle traversed every 19 years. Life as a cycle does not mean we constantly find ourselves back where we started. The circle is actually a spiral — and when we come back to the beginning, we must ask ourselves: Are we higher than when we started? Have we improved? This is the meaning behind a birthday, or any yearly occasion — evaluating how we have used the previous cycle and where we are headed now.

“Kedoshim tihiyu ki kadosh Ani Hashem” (Vayikra 19:2). Hashem epitomizes kedushah; He’s separate from anything else we know. And He instructs us to emulate His kedushah. This means maintaining self-control over our environment and utilizing our G-d-given talents and possessions for the right purpose.

Kuf’s letters can also spell “kof” (monkey), a poor imitation of a human being. In many physical aspects it closely resembles man, but it is lacking intellect and depth. Humans imitate by nature. When we forget that our job is to copy Hashem, we end up copying all the wrong things: how people dress, speak, have fun. We become a poor imitation of what a human being is meant to be.

The yetzer hara does not appear to us openly — it tries to convince us that a lowly act is actually one of kedushah, while it is in fact an imitation. Kuf is the only letter that goes below the baseline (that is not a final letter), alluding to the possible corruption of kedushah. Kuf is made of a reish and a zayin, which spells “zar,” meaning foreign — avodah zarah is the distortion of spiritual connection.

But the same reish and zayin can spell “zer” — crown. This is the message of kuf: Wherever we find the greatest possibility to fall, there is the greatest potential to connect to transcendence.

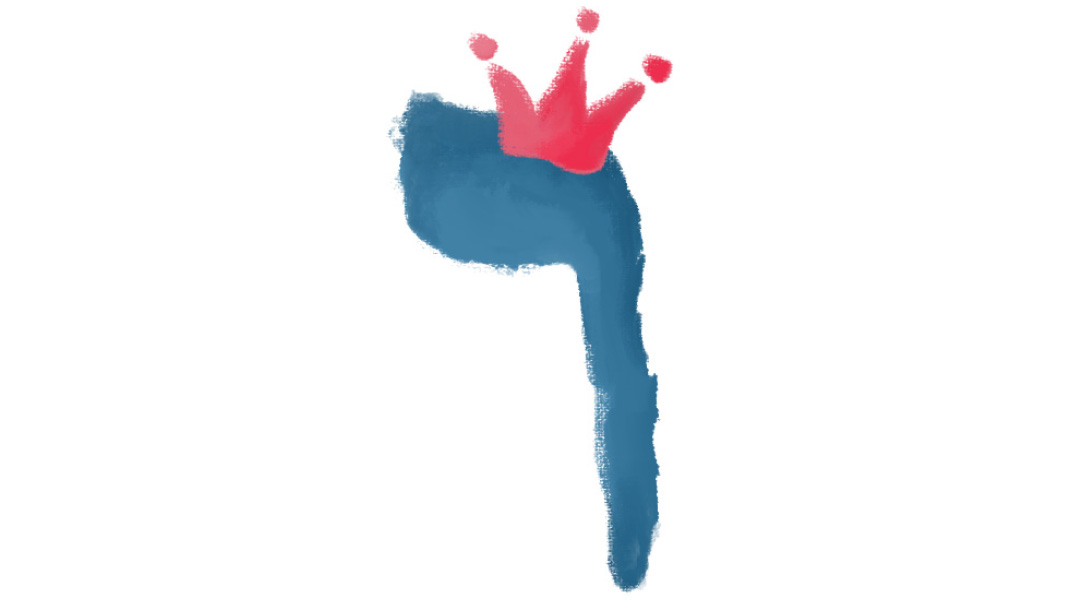

Reish

Name: Rosh (head/leader)

Gematria: 200

Shape: Curved over, very similar to daled

Middah: Leadership

The letter reish closely resembles the word rosh, head (Osios Rabbi Akiva). If we follow Hashem and His Torah we are told, “Unesancha Hashem l’rosh — Hashem will make you a head,” (Devarim 28:13). A paradigm for the nations of the world.

In contrast, when the Meraglim returned with their false reports on Eretz Yisrael, the people were scared and cried, “Nitnah rosh v’nashuvah mitzraymah — let us appoint a leader and we will return to Mitzrayim” (Bamidbar 14:4). Reish is a letter of leadership — but a leader can be fake, appointed for all the wrong reasons.

Herein lies the paradox of reish; with all of its potential it can be sorely misguided. Reish is a rasha, who turns his back on the kuf — the kedushah of Hashem (Shabbos 104a). Reish is the number 200; we learned with the letter beis that two is indicative of the dichotomous world we live in where we must properly exercise our bechirah, our free will to choose properly. The reish is the one who makes the wrong choices.

The Gemara (ibid.) goes on to explain that the leg of the kuf is suspended so that the rasha can reenter through the top.

Structurally the kuf is very similar to the hei, with an opening at the top — that we explained previously is the gateway for a person to return if he falls. In the case of the kuf, the reish or rasha does fall below the line. He’s in that dark, awful place. But the reish is like a door, which can swing around from its top left corner hinge so that it actually faces the kedushah instead of disgracing it (Magen David). The reish can rise when he clings to Hashem and begin to make good choices again.

Too often, we get so caught in a web of mistakes that we are not willing to do an about-face. But we are never allowed to think, “It’s too late, I’m too far down!” There is always a point at which we can stop — take a good look with our head, our minds, and make a rational decision.

The name reish is related to rash, poor; its shape resembles that of a bent-over person. We see a very similar shape in the daled, which also means poor. The difference is that the daled has a sharp edge, a corner, also known as a “yud.” The reish is lacking this yud, this point of spirituality in his life. A person is never truly poor when he is connected to Hashem. But the reish is devoid of this connection, so his poverty is meaningless; his struggle has no ultimate purpose.

This yud is also indicative of Olam Haba. Someone who goes through life thinking that This World is it — that there’s nothing beyond that we are striving for — is missing a core aspect of Judaism which can make all of his service meaningless. For this reason, in sefer Devarim, the daled in the word “echad” of the Shema (Devarim 6:4)is enlarged. In contrast, in the pasuk “ki lo sishtachaveh l’eil acher,” you must not bow down to another god” (Shemos 34:14) the reish in the word “acher” — referring to a god that isn’t Hashem is enlarged. The Torah is going out of its way to point out the vast difference between these visually similar letters. The shape of both is so close — and yet when missing this one point of focus, worship of Hashem becomes worship of something else entirely. When we invest, spend time and money, work hard on a project or recipe — we’ve got to ask ourselves: is this for “Echad” or for “acher”?

We cannot go through life by rote. Our job is to use our heads, to think about what we are doing, to lead ourselves with the values of one who looks toward kedushah.

Connection between Kuf and Reish

These two letters demonstrate the opportunity we have in life to connect to something above us that makes us holy, or to choose improperly and fall. Either way, we always need to remember that there is a possibility to do teshuvah.

Mindel Kassorla is a teacher, graphic designer, shadchan, and Mishpacha contributor. Her older sister, Cindy Landesman, is the head mechaneches of Shearim Torah High School for girls in Phoenix, Arizona, and the director of its Shaarei Bina adult women's education program.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 857)

Oops! We could not locate your form.