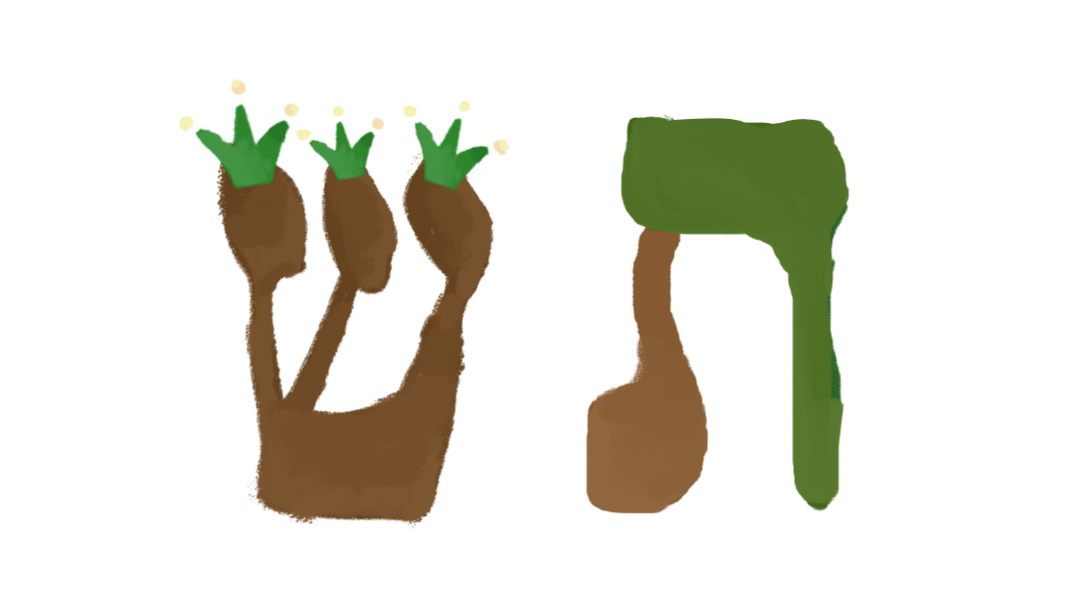

Shin-Tav

| October 10, 2023Are our biases blocking us from effecting change?

Shin

Name: Year, change, tooth, teach

Gematria: 300

Shape: Like a three-pronged crown or tree or flame

Middah: Change

“Ani Hashem, lo shanisi, I am Hashem, I have not changed” (Malachi 3:6). Hashem is the One absolute constant. His Torah, the expression of His Will, is likewise unchanging. Everything else is subject to shifting times, fads, and whims. Nothing in the world stays the same — it looks drastically different from how it did 1,000 years ago! But the “life source” of the world is its connection to one stable core.

This relationship between constant and variable is similar to a flame flickering in a gentle breeze; sometimes the flame disappears for a moment. But the fire still burns, and so the flame reignites. This is the image of the shin, whose shape resembles a flame. The word for fire is aish, made up of the letters alef (signifying one Hashem) and shin, indicating an expansion stemming from the core. Even the sound of the shin is similar to a sizzling fire. When we stare into the eye of a flame, it should remind us that while circumstances feel shaky and unpredictable, our job is to maintain connection with the Source of our energy.

We go through a yearly cycle called shanah, in which each year is different from the last, as we constantly strive to make positive changes in our lives. The word “shin” can also mean “learn,” “sharp,” and “tooth.” What’s the connection between these words? Learning affects progress when the information is broken down into smaller pieces that are easier to swallow. Huge improvement can feel overwhelming; the secret to making change is through small steps.

The three branches of the letter shin represent two opposing forces — change and consistency and expansion and structure — and a meeting point. The right side of the letter is chesed, the middah of Avraham Avinu, and the left is gevurah, the middah of Yitzchak Avinu. The center is the synthesis of the two, tiferes (splendor), the harmony of Yaakov Avinu. The Maharal explains that the shin itself symbolizes two people, each coming with different approaches, who ultimately find shalom through compromise.

Three also relates to the primary colors that make up a rainbow, the emblem of shalom. Its shape is an inverted bow, a sign used to show peace.

Shin looks like a three-pronged crown, representing the three areas of behavior we aim to master: thought, speech, and action. Shin’s gematria is 300, with every branch ideally holding a value of “100 percent” — completion in each realm. While absolute perfection may seem unattainable, the upward-reaching branches of the shin remind us to keep stretching toward our highest goals.

The Gemara (Shabbos 104a) explains that shin is related to sheker, as the other two letters of sheker — kuf and reish — come immediately before the shin in the alef-beis sequence. Shin, the symbol of shalom, jumps to the head of the word — because any lie must appear beneficial and peaceful at first glance. Upon looking deeper, you can see beneath the faulty veneer. It’s instructive that the letters of sheker are all next to one another, while the letters of emes (alef-mem-tav) span the whole alef-beis. Dishonest people will always try to align themselves with those who share their views so they can stay narrow-minded. To reach the emes, we need to expand our view and see beyond what is directly in front of us. We must be open to seeing a broader picture.

Life has ups and downs; even as we try to reach up, we inevitably fall. And so the same letter that indicates growth and learning is also connected to teshuvah, from the root “shuv.” The word kaper (atone) has a gematria of 300 as well. Yom Kippur is a day when we clean the slate, return to our Source and starting point, and realign with the goals we’re reaching toward.

Tav

Name: Sign

Gematria: 400

Shape: Dalet and Nun combined

Middah: Emes

“…the letters of emes (truth) are distant from one another… because while falsehood is easily found, truth is found only with great difficulty” (Shabbos 104a).

The first three words of Torah, “Bereishis bara Elokim,” end with a tav, alef, and mem, the letters making up the word emes. At the culmination of Creation (Bereishis 2:3) alef, mem, and tav appear again as final letters, this time in order. Truth is weaved into the fabric of the universe. The “work” of each week is to “unscramble” the hints of truth, to take situations that are unclear and make sense of them.

Hashem’s seal is truth (Shabbos 55a), indicating that truth is embedded in the world, though it can be elusive. What is my true motive? What is the best course of action? Our foremost consideration should always be what Hashem desires from us, represented by the alef at the beginning of emes.

Tav is at the end of the word emes, showing us that the path to truth is paved with detours and distractions, so we need to have a clear goal in mind that will carry us through.

The more obvious path may be easy to follow and have lots of convenient shortcuts. We can get lured by quick fixes and simple solutions, but when we push ourselves to think harder, we find that these aren’t going to help us reach our destination.

“Emes mei’eretz titzmach” (Tehillim 85:12) — describes truth sprouting from the ground like a plant. Initially, our efforts feel futile. Our acts of kindness yield no results. Our tefillos go unanswered. We’re in the dark, and we feel like whatever we’re doing is meaningless. However, with time, truth emerges with strong foundations, just like a seed pushes through the dark soil, and sprouts.

Patience through this process requires humility, represented by the shape of the tav, which is made from a daled and a nun. Dan is the shevet that was the last one in line when Bnei Yisrael traveled (similar to the tav, which is the last letter of the alef-beis). Dan’s job was to pick up the things left behind and return them; they could have felt like their job was trivial, that as the farthest from the Mishkan their value was less. Understanding one’s place in the larger picture — and trying to uncover what it is Hashem wants from you there — stems from humility. With humility, even when your role isn’t glamorous, you feel a sense of pride in doing what you’re meant to.

There is a large letter tav in Megillas Esther (9:29). Esther lived her life asking, “What does Hashem want from me here? For what purpose am I in this position?” And through her own introspection, she motivated Klal Yisrael to do the same.

The literal meaning of tav is a sign, as we see in, “v’hisvisa tav” (Yechezkel 9:4) — you should mark a sign. Sometimes we’re convinced we’re headed on the right path, acting in the name of truth, while in fact our biases are taking us astray. We need a sign — a marker — to keep us focused: A mantra, a good friend to redirect us, or an action we build into our lives as a constant reminder.

In the Bris bein Habesarim, Avraham was informed that Bnei Yisrael would be in galus for 400 years, the gematria of tav. What kept Avraham — and Bnei Yisrael — strong through this difficult reality? A focus on the destination, the ultimate purpose. We often make reference to Mitzrayim, remembering what made us who we are, reminding us to be considerate and compassionate toward the downtrodden, because we were once in that situation. The process was hard — but when we look back on it and see what grew out of it, we can understand the purpose.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 863)

Oops! We could not locate your form.