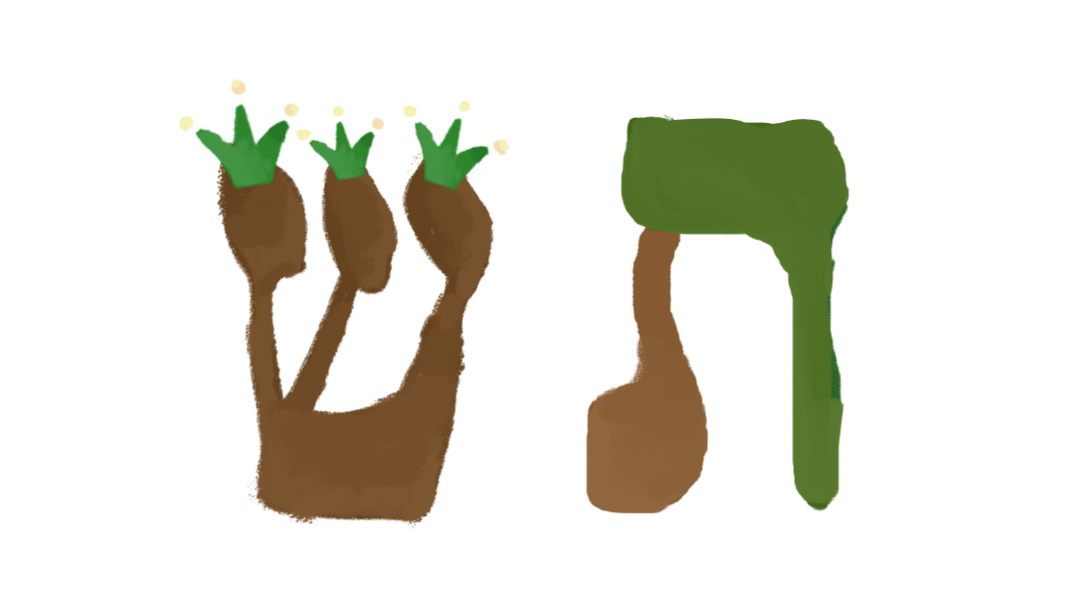

Pei-Tzadi

| August 1, 2023Speech is the expression of the soul

Pei

Name: Mouth

Number: 80

Shape: Kaf and an upside-down yud in the center

Middah: Communication

The letter pei in its full form is pei hei — peh, a mouth. Speech, which we do with our mouths, is the expression of the soul. The Torah (Bereishis 2:7) tells us that when Hashem implanted Adam with a neshamah, this made him into a living being, which Targum Onkelos explains as “one who speaks.” So many aspects of Judaism are founded on speech: vows are only binding if spoken, Shabbos must be made holy with words, teshuvah must be verbalized. In other relationships the same holds true: we can’t assume people are mind readers; it becomes our responsibility to communicate what’s in our heart.

The pasuk states, “V’shinantam levanecha v’dibarta bam — teach words of Torah to your children and speak them” (Devarim 6:7). The oft-quoted principle of “actions speak louder than words” isn’t exclusionary. When you’re cooking up a storm for another family, say to your family members, “I’m making this food for someone because they had a baby and need help now.”

Pei’s gematria is 80, the age when Moshe Rabbeinu gave over the Torah to Bnei Yisrael; his mouth was the conduit for bringing Hashem into this world. Pirkei Avos (5:21) explains that age 80 is the age of gevurah, strength. Not physical prowess, but rather the point when one’s spiritual might outweigh his physical. On Har Sinai, Moshe overcame his limitations by abstaining from food and drink, so Hashem rewarded him by healing his mouth from its childhood wounds (Yalkut Shimoni). We can tap into this koach of 80 to overcome the urge for using our mouths in natural, albeit damaging ways, and elevate them towards a G-dly purpose.

Previously Moshe had said to Hashem, “Kvad peh u’kvad lashon anochi. I am slow of speech and slow of tongue.” (Shemos 4:10) Moshe’s speech impediment made him sound almost childish, and so he begged not to be His representative. But Hashem replied “Mi sam peh l’adam? Who gives humans speech?” (ibid 4:11) The same Hashem who had caused this was of course capable of making him heard. When we feel stuck, like we don’t have the words to fill the hole in someone else or to rectify the situation, that is where we must reach out to Hashem for help. “Hashem sefasai tiftach....”

There is a bent pei and a straight pei (final pei) because sometimes you need to open your mouth to speak, and sometimes you need to close your mouth, to remain silent (Shabbos 104a). When we want to understand Torah, or we notice someone who needs encouragement, we must speak. But at the same time, we hold back from saying what may be hurtful, we stay quiet to learn from others. It’s an unfortunate reality that so often we get these mixed up — remaining silent in place of speaking, and chattering instead of listening.

The pei is composed of kaf with an upside-down yud in the center. Kaf is a kli, an empty vessel to be filled. With what? Yud, which we explained previously as the handprint of Hashem. “Yimaleh pi tehilasecha, my mouth should be filled with Your praise” (Tehillim 71:8).

When pei is filled with yud, the negative space inside forms a beis. This is the Beis Hamikdash, the pinnacle of connection to Hashem on Earth. The Leviim used their voices to create greater connection, the Kohanim spoke as they gave korbanos, and this was the ultimate “Beis Tefillah” of the world. We too can make our “pei” into a “beis.”

As the 17th letter of the Alef-beis, pei is inherently connected to tov (whose gematria is 17). The power of speech was given to us as a tool to express what is in the recesses of our minds, and it’s our mission to fill it only with good, with modes of connection to Hashem and to others.

Tzadi

Name: Tzaddik, Hunt

Number: 90

Shape: Made of a nun and a yud

Middah: Righteousness

This letter is often pronounced “Tzaddik” — not as a misnomer, but rather because this is its essence. “A bent tzadi and a straight tzadi, like a bent tzaddik and a straight tzaddik” (Shabbos 104a). Tzadi is made up of a nun that’s bent forward with a yud sticking out of the right side. The final tzadi has the same form, but instead of a bent nun, there’s a straight, final nun.

A tzaddik is bent, one who humbly sees himself as Hashem’s messenger, not particularly special in his own right. In the next world, the tzaddik will stand upright. We may relate to tzidkus as perfection, but in truth this is a kind of righteousness that we can all access — in viewing ourselves as someone doing their job in this world by effectively using the resources Hashem gave us.

According to the Arizal, the yud is positioned in the reverse and is looking back towards the Ten Utterances Hashem used to form the world. According others, the yud is positioned forward and toward the nun — the 50th level of transcendence that he’s trying his whole life to reach. Yud is the tiny spark of potential, while nun is the actualization. A tzaddik knows why he is here — to take the abstract ideas of spirituality and bring them into existence, to make Hashem real to us here on Earth.

This is the tzaddik’s balanced perspective — looking at how he got here, and understanding the end goal. “Tzaddik yesod olam” — the tzaddik is the foundation of the entire world (Mishlei 10:25). He lives with a clarity of purpose which enables us to be inspired and access our own commitment to a mission.

“Tzad” means “hunt” — tzaddikim seek out opportunities to do mitzvos and improve. There are countless stories of gedolim who did miniscule acts of kindness that may seem to us as things we could easily emulate. In truth what makes them tzaddikim is not that they did it, but that they sought it out — they actively searched for these opportunities.

A newborn is instructed, “Be a tzaddik and not a rasha” (Shabbos 30b). It’s not enough to merely tell him “be a tzaddik,” because if we do a mitzvah, the negative thoughts kick in again to make us regret it all. We extend ourselves for another and then wonder: Am I being taken advantage of? Did it even matter that I went to that wedding? This is where we need to stand our ground most, and reaffirm that we’ve become a better person from it, so that our submission to kindness is empowering, not demoralizing.

Tzadi is the 18th letter, “chai.” “Tzaddik b’emunaso yichyeh — the life source of the tzaddik is his emunah” (Chavakuk 2:4). Emunah, or ne’emanus (loyalty) is the middah of the nun. Nun also signifies nefilah, falling. Even as the tzaddik faces challenge, he has the emunah through his connection to Hashem (the yud) that whatever comes his way is truly for his own good. The tzaddik is consistently trying to live by this key to life, seeing Hashem even in the dark.

“Ben tishim lashuach” — the age of 90 is a bent body (Avos 5:21), when one’s back bows with weakness. More deeply, one who lived his life righteously will have achieved true humility, and no longer bothers himself with petty matters. Most of life has passed by; he understands the necessity of utilizing every last moment.

Read differently, this mishnah can mean, “lasuach” — at 90, one converses. He achieves a heightened level of tefillah; he can speak directly to Hashem. Tefillah is of course the primary tool of the tzaddik, which is why we ask tzaddikim of the generation to daven on our behalf. The more we live life with the values and mindset of a tzaddik, the more access we gain to this beautiful kind of conversation.

Connection between Pei and Tzadi

Pei is the letter of accessing and verbalizing the thoughts of the neshamah, our connection to Hashem. A tzaddik is himself the ultimate expression of G-dliness in this world.

Mindel Kassorla is a teacher, graphic designer, shadchan, and Mishpacha contributor. Her older sister, Cindy Landesman, is the head mechaneches of Shearim Torah High School for girls in Phoenix, Arizona, and the director of its Shaarei Bina adult women's education program.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 854)

Oops! We could not locate your form.