Tes-Yud

| April 25, 2023Nurturing others is the greatest good

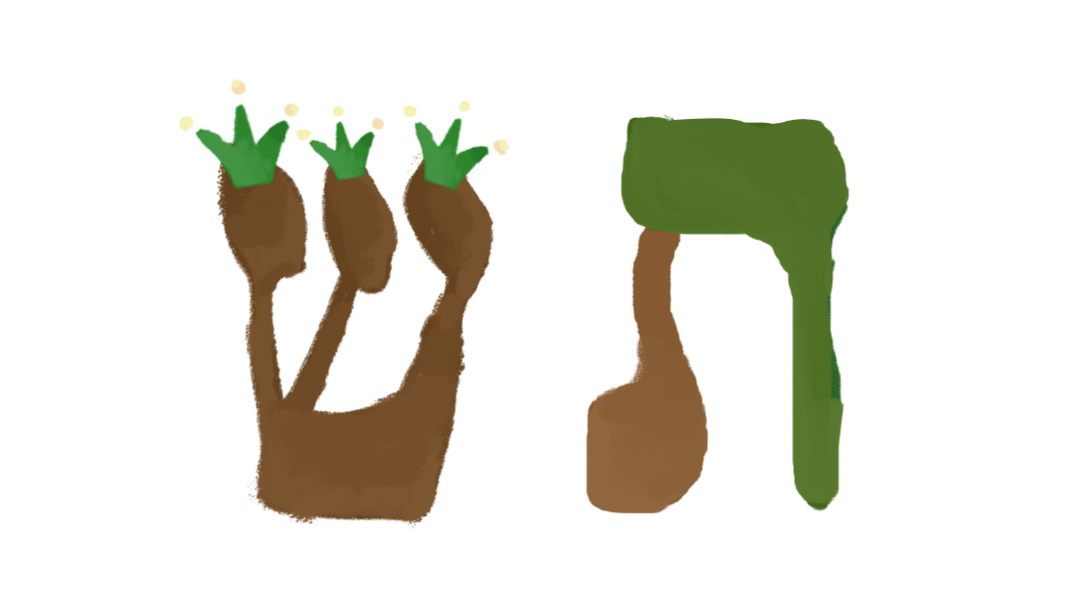

Tes

Name: Similar to “teet,” meaning mud or clay

Gematria: Nine

Shape: A womb (inverted)

Middah: Goodness

“Vayar Elokim es ha’ohr ki tov — Hashem saw the light, that it was good” (Bereishis 1:4). Our introduction to the letter tes in Torah is as the first letter of tov. At Moshe’s birth, Yocheved recognized in him something unique: “Vateire oso ki tov hu — she saw him, that he was good” (Shemos 2:2). In some very old sifrei Torah, this tov is written with an enlarged tes. This was not merely the adoring gaze a mother casts upon her newborn. Moshe was Tov — with a capital Tes. His arrival brought a special burst of light into the world, similar to the light of Creation.

Tes can be seen as an inverted womb; it is number nine, as in the nine months of pregnancy. Taking a piece of oneself and using it to produce another human being, then nurturing it to grow into an independent individual — what greater good can there be?

This is the goodness of Hashem, Who in His kindness produced us and our world, purely for our benefit, and allowed us to become independent beings. In the same vein, Moshe was, in a sense, the one who “delivered” Bnei Yisrael from the “womb” of Mitzrayim into the world, to become a nation in its own right.

Even in his prestigious role, Moshe was “anav mikol adam — the humblest of men” (Bamidbar 12:3), who took no credit for himself. The shape of the tes has a straight side on the left with a crown atop it, and a bent-over edge on the right — illustrating a man bowing and humbling himself before Hashem, acknowledging that we are servants of the King.

The humble person carefully conceals his good actions, and internalizes the idea that only Hashem needs to know. In our modern world, we are used to thinking that the best is the biggest, the loudest, the most public. But tes teaches us otherwise: just as the womb encases the precious child, sometimes that which is most valuable is hidden from plain sight.

The Midrash Osios D’Rebbi Akiva explains, “Do not read it as tes, rather as teet (spelled tes-yud-tes). Teet, clay or mud, is a most basic substance — it’s dirty and ugly. But with time and patience, it can become a pot, a brick, a house!

Tes does not represent the kind of happy-go-lucky goodness of everything readily meeting my expectations. It is a hidden, objective goodness, one that begs us to look beyond externalities. The first set of Luchos were given under pristine conditions, but when things were not perfect, we panicked and failed. Interestingly, the first listing of the Aseres Hadibros did not have one instance of the letter tes; something was missing. We need to be able to live with setbacks! To build resilience, bounce back. In contrast, the second set of Luchos were given after we did teshuvah and with much less fanfare. This time, the text had a few changes, including the addition of a tes in “lemaan yitav lach” (Devarim 5:15). This new set also had 17 additional words, the gematria of tov.

While experiencing a challenge, we are not always able to see with clarity that it is good. But when we look back and understand how even the most tragic events built massive legacies, we can believe that there is always a core of Good.

The word emes is spelled alef-mem-tav, gematria 441. Add these digits (this is known as mispar katan) and you get — nine! Actually, nine is the only number that every single one of its multiples will always result in a number whose mispar katan is nine (36, 72, 441, etc.). No matter how concealed it may be, the good is always there.

Yud

Name: Yad — hand

Gematria: Ten

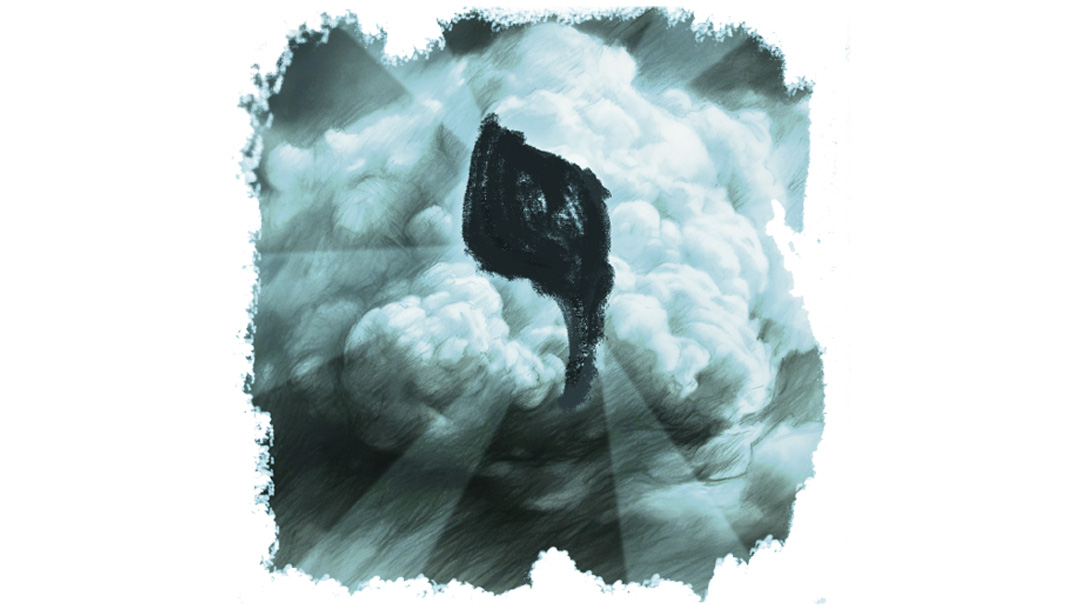

Shape: The smallest letter

Middah: Contraction

Yud is paradoxical in nature. On the one hand, it is the smallest letter in the alef-beis, virtually invisible. Its mispar katan (1 + 0) is one, telling us it is intrinsically linked to singularity. On the other hand, it is number ten in the series, taking us to the realm of two-digit numbers and creating a foundation for that which is to come. It is unification and multiplicity all in one.

A prime example of this is when ten men join for a minyan. Before they are a complete ten, they are a bunch of individuals with no unifying factor. When they make ten, they become one — a unit capable of something so much greater.

The top point of the yud is narrow, and then as it moves lower it expands — contraction for the purpose of expansion, pulling back myself and my individuality in order to create. In Kabbalah we are told that Hashem “pulled back,” so to speak, His infinite nature to make space for our world. We are asked to emulate Hashem by making space for others in the world He gave us.

Yud can be read as yad, meaning hand. A baby is born with closed hands; he knows only to take. But he dies with hands open. Life is the process of becoming a giver — relinquishing pieces of ourselves to forge connections and build others. “Yedid” in Torah describes a deep friendship. Embedded in this word we see two yuds joining: two people each contracting, allowing the other into their space to hear and respect one another.

The pasuk in Yeshayahu (26:4), “Ki b’kah Hashem tzur olamim — Hashem is the rock of eternity,” can be read midrashically as follows: “With the letters yud-heh Hashem created worlds.” As we saw previously, heh was used to create Olam Hazeh. Now we can see how yud is connected to Olam Haba. It is especially unique in that it is the only letter written above the baseline, disconnected from where all the rest sit. Yud essentially challenges us to rise above the minutiae of life to achieve a higher state of selflessness and spirituality, of connecting to Olam Haba even while in Olam Hazeh.

Spiritual connection is found in smallness. Har Sinai was the shortest mountain, Moshe the humblest man, and Klal Yisrael (called by names starting with a yud: Yehudah, Yaakov, Yeshurun, Yisrael) is the tiniest nation. By taking up less space, less of the limelight and attention, we allow ourselves to connect to a world with no physical dimensions whatsoever.

The number ten appears throughout Torah and Jewish life: from the Ten Makkos, to the Aseres Hadibros, to the Aseres Yemei Teshuvah, and so on. We use a base-ten system of numbers, we have ten fingers and ten toes — it seems as though Hashem created us to count to ten!

The number ten actually takes us back to the Asarah Maamaros (Ten Utterances) of Creation. The world is made up of physical particles that are infinitely small, but it is also made up of tiny spiritual particles — of yuds. Yud is a DNA stamp, a genetic code, a handprint on every single facet of creation, which allows us to see the Yad Hashem wherever we look. Olam Haba is not mentioned anywhere in the Torah. And yet, living in This World with eyes open, a person cannot help but come face-to- face with the reality that there must be a World to Come. The yud is there, as small as it is — our job is to find it.

Connection of Yud to Tes

Tes is the letter of “pregnancy” — a womb protecting and nurturing a precious core. Yud is the process of contraction for the purpose of expanding this core into a greater place and purpose.

Mindel Kassorla is a teacher, graphic designer, shadchan, and Mishpacha contributor. Her older sister, Cindy Landesman, is the head mechaneches of Shearim Torah High School for girls in Phoenix, Arizona, and the director of its Shaarei Bina adult women's education program.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 840)

Oops! We could not locate your form.