Kaf-Lamed

| May 16, 2023

Kaf

Meaning : Bent

Number: 20

Shape: Curved like a cup or spoon

Middah: Resilience

Previously we discussed the letter beis through the lens of bitachon, of seeing contradictory elements in the world and believing it all comes from Hashem. Now with the letter kaf, we have a multiple of two — 20 — and we take that reliance upon Hashem to the next level.

Kaf means bent. When faced with a difficulty, we can either stand our ground and cling to what we wish were happening, or we can bend (Mayanah shel Torah). Rigidity is terribly limiting; when we approach life with flexibility, allowing ourselves to lean into situations and accept when things don’t go as we planned, it’s actually quite liberating. This is true resilience — not the opposition of challenge, but the ability to live with it and rise above it.

Spell out the number 20 in Hebrew, esrim, and you get the letters ayin-sin-reish-yud-mem, whose gematria is 620. This is also the value of the word “keter — crown,” which begins with a kaf, because when we bend our will to Hashem’s, we’re recognizing His Kingship. (Ben Yehodaya)

Perhaps we think that if we bend and relinquish control, it’s a sign of weakness. But the ability to overcome our instinctual reactions, to grow internally and build ourselves as people — that is real power and accomplishment. In our interactions with others, as we grow and mature, we realize that the greatest show of strength isn’t getting our way — it’s giving in.

Other meanings of kaf include the following: spoon/ladel (Bamidbar 7:14), palm of the hand (Tehillim 128), sole of the foot (Yechezkel 1:7), palm tree branches (Vayikra 23:40), and hip socket (Bereishis 32:26). A common thread we see in all these is an object that is bent, which holds something or lends support. Here the kaf is teaching us how to respond to a challenge. When life throws us a curveball, instead of jumping out of the way, catch it! We’re by nature comfort-seekers; we resist unexpected changes and difficulty. But kaf says, “Hold on to it! Incorporate the challenges Hashem gave you into your life and make them meaningful.”

A kaf at the start of a word means “like” — as in not exactly, but just about. How often do we get thrown for a loop when things are kind of what we wanted but not exactly? Husband goes shopping and gets the shredded iceberg lettuce instead of the romaine. Friend picks you up for the shiur… ten minutes late. Are we grateful? Do we complain? Resist? When something is like you wanted it to be, and not just so, kaf says, don’t let yourself get sidetracked — bend a little and work with what you’ve got.

Kaf is the first letter we have so far that has another form — the final kaf, which comes at the end of a word and has a straight bottom extending down. The difficulties we experience help us grow, but once we’ve passed through them, the final kaf teaches us to then extend to others.

The final kaf means “you” (as in lecha) or “yours” (as in shelcha). We can take the resilience we’ve built and use it to understand someone else’s challenge. We can show empathy and concern, which may help them get through it. And if they’re open to hearing the lesson of the kaf, we can share that, too.

Lamed

Meaning: Learn/teach

Number: 30

Shape: Kaf with a vav on top

Middah: Achievement

Lamed is the tallest letter, and as such, represents greatness. The secular world defines greatness as fame and popularity. Jews use a different measure. It’s the greatness within, the internal achievements, which define a person. Lamed is the ability to use our experiences as a means to soar.

The base of the lamed is a kaf. As we said above, kaf is the ability to bend, and to hold a new reality in place of resisting it. The vav atop the kaf tells us to use what we’re holding as a means to move upward, to become better people, not despite our challenges, but because of them.

The root lamed-mem-dalet means both to learn and to teach, for we’re always students — learning information from our world, and then “teaching” it to ourselves by making practical use of it. We’re meant to start each day with an eye toward what we might learn, and end the day asking introspectively — “What wisdom did I gain today?”

When lamed is used as a prefix it means “to” or “going toward.” When saying goodbye to someone, we shouldn’t say, “lech b’shalom” but rather, “lech l’shalom” (Berachos 64a). A person doesn’t leave “in peace” but rather moves toward it — because life is a journey. We’re on our way, but we need to live life knowing we are never fully there. The only time we do say “lech b’shalom” is when a person is niftar, as they’ve reached their final destination and peaceful place.

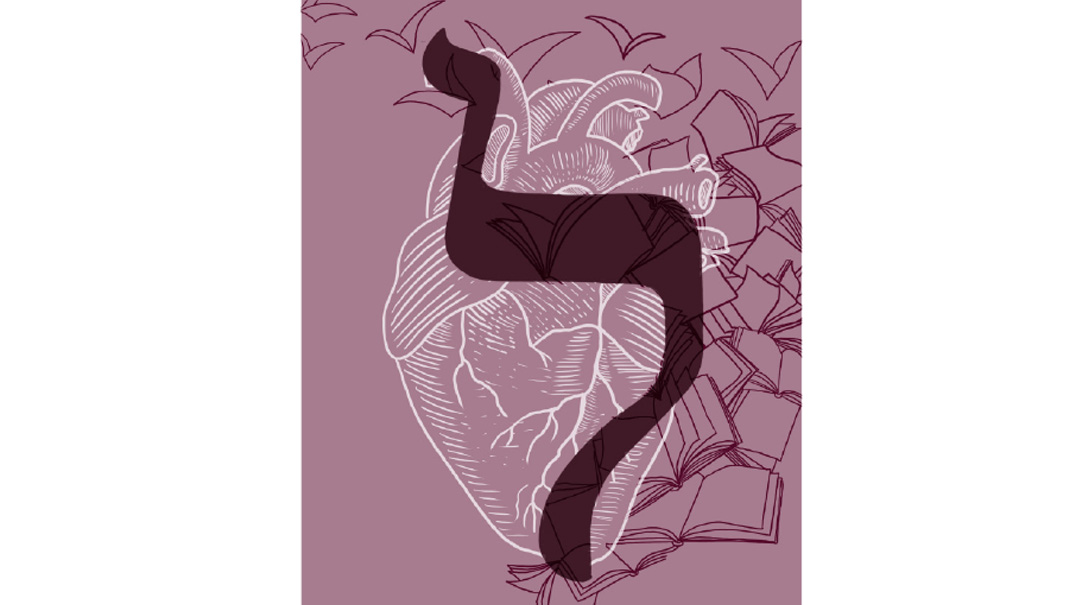

Sefer Osios d’Rabi Akiva explains that lamed-mem-dalet can also be read as an acronym for “lev meivin daas — a heart that understands wisdom.” You can’t just know with your brain; you need to feel it with your heart. This is the concept of “v’hasheivosa el levavecha” (Devarim 4:39) — the Torah must penetrate deeply into your heart and affect how you live.

The root lamed-mem-dalet first appears in Sefer Devarim, most appropriately as Moshe is reviewing the laws that Bnei Yisrael will need to put into practice in Eretz Yisrael. There they won’t have Moshe with them any longer, and they now must accept personal responsibility to soak in the Torah and make it their own.

The word “lev” (heart) is made up of lamed-beis, which can be seen as lamed multiplied by two, meaning two lameds. Two lameds facing each other form a heart with the two kafs (Imrei Shefer). The vavs come out like the two blood vessels that enter and exit the heart. One brings in deoxygenated blood; the other transports the oxygen-enriched blood to the body so it can function properly. This structure tells us that when we take in information, we need to process it and enrich it with our own personal touch, make it our own, then release it to impact the world.

Thirty is the number of days in the Jewish lunar month. During the first 15 days, the moon increases in size, and during the last 15 days, it deteriorates, representing the ups and downs of life. Through all of it, there is a message to be found. In good times, we’re challenged to remember that we need Hashem. Through the tougher times, it’s hard to find Hashem.

It can be frustrating sometimes when we feel we have stretched ourselves so much in one way, and then a new situation comes up that challenges us from a whole different angle. But Hashem put us there for a reason — to learn something new.

The Torah tells us in Devarim that one day in the future Hashem will need to send us out of Eretz Yisrael to galus (Devarim 29:27). In this pasuk there is a large lamed, driving home the same message: Every place Hashem sends us is no coincidence, rather we’re meant to learn something from the particular place we are sent. It’s a life-transforming mindset to always be able to say to ourselves, “I’m here for a reason; I’m here to grow.”

Connection between Kaf and Lamed:

Kaf is the ability to adapt ourselves to life’s challenges. Lamed infuses the heart with what we’ve learned from the challenge, so it can deeply affect our lives and help us achieve greatness.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 843)

Oops! We could not locate your form.