Judgment, Timing, and Luck

While luck and timing were never his friends, have they now joined forces to threaten de Blasio's legacy? The story of a relationship gone awry

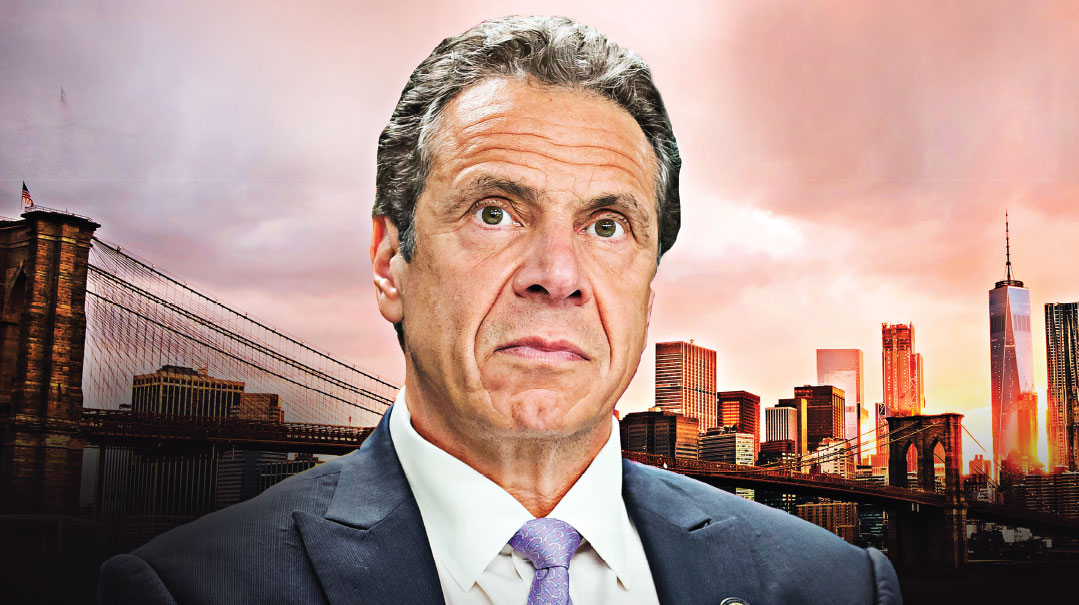

Photos: Ben Kanter

"So, what I found is, when I started running for mayor, it was just like, let’s get this over with. I am who I am, I’m not changing, it’s not like something I could change — I couldn’t fake it if I wanted to, it’s too deep in me. So, I just kind of came out with it. What’s amazing is people… they didn’t like my choice, but they did like my honesty."

He was talking about his affinity for the Boston Red Sox on a sports radio show, but Bill de Blasio could have been discussing almost any area of his life.

Honest, but sort of obstinate; decent, but without the easy charm that comes naturally to other politicians.

He was mayor. Of New York. How hard could it have been to pretend to exchange the team of his youth for the Yankees?

For Bill de Blasio, it was very hard.

In time, this inflexibility would darken the final stretch of his mayoralty in New York City, perhaps even tarnish his legacy — at least as it pertained to the Orthodox Jewish community with whom he’d gotten along so well for so long.

What happened?

Where did things go wrong?

How did Bill de Blasio lose one of his most carefully cultured relationships?

The Fixer

Bill de Blasio has spent most of his adult life on a one-way trip to making a difference.

He didn’t have an easy childhood. When he was five years old, in 1966, his parents divorced, and his mother, Maria, took her children back to her family in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Bill’s father, Warren Wilhelm, an injured war veteran, more or less disappeared from their lives, and Maria’s family — the de Blasios — raised her three boys. Those years formed Bill’s allegiance to the Red Sox, the team that would give the young man an identity and cause at a time of instability.

When young Bill was 18, his father, suffering from cancer, committed suicide.

Years later, when Bill’s daughter Chiara would go public about her struggles with substance abuse and depression, it was initially perceived as a politically motivated move — the family was getting the dark story out of the way before the media uncovered it. But Bill and his family disproved the theory. After publicizing the video, the young woman and her parents used her struggles as a springboard to open a discussion about mental illness in general, launching a city-sponsored texting service for suffering teenagers.

“I never really got to know my father,” de Blasio said at the time Chiara emerged as a spokesperson for depression, “but I saw what happens when a problem is unaddressed.”

This determination to fix every problem, noticeable or otherwise, would generally serve the mayor well — except when it wouldn’t. The spring of 2020 would be one of those times.

In his high school yearbook, friends predicted that one day, when Bill was elected president, they’d boast that they once knew him. He was bright and determined and always a champion of the underdog, trying to right what he perceived to be wrongs.

After earning a B.A. in metropolitan studies from NYU and a master’s degree from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, de Blasio took a job at the Maryland-based Quixote Center, where he was a regular at protests and rallies, getting arrested more than once. In 1988, he traveled to Nicaragua to support and assist the ruling socialist government, the Sandinista National Liberation Front, which was opposed by the United States government.

The socialist sympathizer and political organizer then moved back to his birthplace, New York City, where he worked for a nonprofit aimed at improving health care in Central America. In 1989, he became a volunteer coordinator for David Dinkins’s mayoral campaign, and after the election, de Blasio was hired as an aide at City Hall.

During that stint, de Blasio met his wife, an African-American fellow aide, Chirlane McCray, but that’s not the only way his life changed.

Working for Dinkins gave him a close-up view of the 1991 riots that erupted after a car accident involving a chassidic driver and African-American child. The young boy was killed and a mob, crying for “hassidic blood,” roamed the streets of Crown Heights for three days, forcing Jewish residents of the neighborhood to barricade themselves in their homes, paralyzed by terror. Dinkins made the fateful decision to let the people express their rage, and it resulted in the murder of a young chassid, Yankel Rosenbaum.

De Blasio was haunted by this.

“He saw a mayor lose control of a city,” says a close confidant of the mayor, “and it kept him awake at night. He thought Dinkins should have invoked a curfew, should have let the police clamp down, and that hadn’t happened.”

This too would prove significant in the spring of 2020.

Back in the ’90s, de Blasio experienced a string of successes. He oversaw Charles Rangel’s successful 1994 reelection to Congress, and was then appointed as regional director of Housing and Urban Development. Along with putting him in the orbit of the Clintons, it exposed him to the reality of those who live in substandard housing, giving him a feel for the street. Unusual for a high-ranking federal appointee, he spent lots of time in the projects he was meant to be serving, listening to tenants and hearing their grievances. They would come to see him as a friend, and eventually, de Blasio would be the one to launch the very effective online “worst landlords list,” waging war on irresponsible building owners by making their transgressions public knowledge.

In 2000, de Blasio served as campaign manager for Hillary Clinton’s Senate bid. As part of his efforts to build support for Clinton, the democratic socialist started to interact with the Jewish Orthodox community and its leaders, and this would help him less than a year later.

He and his wife had settled in Park Slope, a neighborhood they still consider home (although their house is rented out while they live in Gracie Mansion), from where he decided to run for the New York City Council in the 2001 election. The district includes Boro Park and Kensington, and de Blasio spent his evenings at simchahs and yeshivah dinners, meeting the power brokers of the frum community, learning to shake hands, dance with the mechutanim, and say mazel tov.

The frontrunner was a Jew named Steve Banks, but with persistence, hard work, and a genuine feeling for two causes close to the heart of community leaders — education and poverty — de Blasio built up a network of support and won. (Later, in a de Blasio “good guy” move, he appointed Steve Banks as his commissioner of Human Resources.)

One of de Blasio’s first decisions was to hire Rabbi Yeruchim Silber, whom he’d gotten to know and respect during the campaign, as his liaison to the Orthodox community.

“The fact that he was progressive didn’t make a difference,” recalls Rabbi Silber, currently director of New York government relations for Agudath Israel, “because he was a thinker, he genuinely formed opinions on issues, and each situation had its own approach. He was able to be progressive and still be pro-Israel and in fact, he’s emerged as a leading anti-BDS voice over the years. He has his own mind.”

The de Blasio tenure on city council was largely seen as a success. The rising liberal star was also closely aligned with the Orthodox community, who saw him as unusually understanding to their particular needs and concerns.

In 2008, he took the next step, announcing his candidacy for an office that seemed tailor-made for him — even though he didn’t seem to have a chance. The New York City Public Advocate’s Office had been created less than 20 years earlier to serve as sort of a watchdog for New Yorkers, within the government, with rights to introduce legislation.

It was the perfect role for someone who sees himself as a savior of the underdog and loves a soapbox. Bill de Blasio wanted it badly, but so did Mark Green, the first person to have held the job. He’d taken a break to run for mayor, and after losing, he wanted his old job back.

But in what would become a pattern, de Blasio ran anyway. He and Green were nearly tied, and neither won decisively, necessitating a run-off election.

This time, Bill de Blasio won.

In endorsing him for public advocate, the New York Times had praised de Blasio’s previous efforts to improve schools and help less fortunate New Yorkers. Once he secured the new position, he continued to focus on those causes.

It wasn’t only public schools, says the man who was appointed as de Blasio’s liaison to the Jewish community and remains one of his closest advisors until today.

“It was a respect for education in general,” recalls Pinny Ringel, de Blasio’s senior Jewish communisty liaison. “Private schools as well.”

Ringel was in the car one day with de Blasio, who had just indicated his support to increase funding to a respected Boro Park institution. Someone in the car wondered where the money would come from, and de Blasio pointed out the window at the bumpy street. “These roads need to be fixed, but they’re not as much a priority as ensuring that every child has the education they need to thrive. The roads can wait another year.”

Besides his help when it came to budgets and laws, Jewish community leaders respected de Blasio as a family man.

“He was a decent person, which isn’t always the case in New York politics,” reflects a longtime activist. “He and his wife were the type who moved both their mothers to Park Slope, next door to them, so that they could attend to their needs. That was the sort of value that spoke to us.”

Pinny Ringel had a similar sense. “I worked for Simcha Felder for years, but I developed a relationship with the mayor, I liked him. People might say I’m biased because he’s my boss, but remember — I chose to go work for him after knowing him for eight years.”

The Winner

After four years as public advocate, Bill de Blasio launched his bid for mayor. Early polling placed him fifth in the crowded field, behind Christine Quinn, John Liu, Anthony Weiner, and Bill Thompson.

During that election season, de Blasio garnered media attention when he joined a protest against the closure of Long Island College Hospital and got himself arrested — a throwback to his younger years. Though there were certain chassidic groups that supported candidate Bill Thompson, the overwhelming majority of Orthodox voters were enthusiastically behind de Blasio, campaigning and fundraising for their former city councilor.

After a concerned voter penned a piece criticizing de Blasio’s support of the Marxist Sandinistas in Nicaragua, Yaacov Behrman — a respected Crown Heights advocate and activist — took to the pages of Hamodia to offer his defense of the candidate:

While there may be much to be learned from examining de Blasio’s views and conduct as a young adult, I think we can all agree that his conduct over the last 12 years, when he actually served as an elected leader — public advocate for the last four years and City Council member for eight years before that — gained trust and respect from the Jewish community …The fact that de Blasio sympathized with the Sandinistas 25 years ago should be of little concern to voters. Winston Churchill famously said, “If you’re not a liberal at 20, you have no heart.” This is what many young people did back then.

Slowly but surely, de Blasio climbed in the polls, showing a doggedness that New Yorkers would come to recognize. (In 2019, that same tenacity would hurt him when he persisted with his presidential campaign despite pollsters insisting that he had no chance.)

He won — and New York City changed.

“The deeper you look, the stronger the evidence that de Blasio’s victory is an omen of what may become the defining story of America’s next political era: the challenge, to both parties, from the left,” wrote Peter Beinart in 2013.

He would move New York City left on a practical level, turning liberal values into law. The municipal residents’ cards he introduced allowed illegal immigrants, and even homeless people who could provide a “care of” address, access to necessary services. He personally presided over the first few same-gender marriages in the city. He managed to keep citywide rents nearly in place in his first year, then frozen in the following years.

Yet the liberal darling was also applauded by the Orthodox community, an improbable alliance. He invited visibly chassidic Pinny Ringel to join him in City Hall. Avi Fink, who currently runs the Office of Management and Budget, was a trusted confidant, part of the mayor’s inner circle; and current Assemblyman Simcha Eichenstein later joined de Blasio’s team as director of political and governmental services.

Mishpacha’s Yochonon Donn, who’s been covering the mayor for the better part of two decades, remembers the Motzaei Shabbos before the election.

“De Blasio came to a fundraiser in Boro Park,” says Donn. “He pointed to Pinny Ringel and Avi Fink and said that these are the faces who will be working in his administration. I’ve watched Pinny working for the community over the years and he’s a community treasure. He’s quiet, effective and most importantly, accessible. His loyalty to the mayor is unquestioned, but he’ll do anything for the community.”

Speaking against BDS meant turning his back on part of his progressive base, but the mayor has remained consistent. “From combating anti-Semitism to vehemently opposing BDS, this mayor recognizes the important place the Jewish community has in the fabric of New York City,” says Jane Meyer of the mayor’s press office.

And de Blasio’s universal pre-K coverage, providing access to a free, full-day pre-kindergarten for every four-year-old regardless of family income, was appreciated by his Orthodox constituents along with the rest of the city.

“De Blasio will rightfully be able to point to pre-K as a significant accomplishment: He delivered with a swiftness that even skeptics were obliged to acknowledge, and on a scale that is nationally unprecedented,” wrote the New Yorker.

Out of Favor

But he couldn’t seem to catch a break.

The city was hammered by a snowstorm early in the first week of January 2014, and residents complained that the response wasn’t quick enough. The new mayor apologized — and then it snowed again the next week, another record-breaking blizzard. The mayor decided that the public schools should stay open, a decision that was criticized by parents, teachers, unions, and the media as dangerous.

But the weather was a small issue compared to his relationship with the New York Police Department.

Disappointing his progressive base, the new mayor decided to continue the city’s “broken windows” policy, which focused on arresting citizens for low-level offenses and infractions — trespassing, marijuana possession, suspended licenses, and the like — as a method of preventing more serious crimes. Get them on the small stuff, was the thinking — a policy widely considered to be racist.

In the complex and challenging spring of 2020, the decision would come back to haunt him when he learned that, despite his biracial family and genuine broad-mindedness, many in the black community had stopped liking him.

So at least the police should have liked him, right? Bill de Blasio lost them too, just a half year after taking office, when Officer Daniel Pantaleo tried to arrest Eric Garner for selling loose cigarettes. In his attempt, he strangled Garner to death with a chokehold.

The grand jury declined to indict the officer, and de Blasio reacted by talking about needing to “train” his own son, Dante, who is biracial, in “how to take special care in any encounter with police officers.” Those words were seen as an attack on the police officers, and the city’s largest police union announced that the mayor was no longer welcome at police funerals.

At subsequent funerals, the cops, as one, turned their backs on the mayor.

Police Commissioner Bill Bratton reflected that the experience changed de Blasio, who didn’t quite understand the dislike for him, didn’t yet understand that he’d managed to lose both sides of the room through a mix of bad luck and bad timing. In 2020, however, it would all be remembered.

Meanwhile, de Blasio would win reelection again in 2017, but he never managed to be an “insider.” He was a different sort of mayor from his predecessors, each of whom, in their own way, was seen as being very much part of the New York brand.

It wasn’t just the Red Sox. De Blasio didn’t hobnob well, didn’t gush about the city and its attractions, didn’t frequent the popular restaurants or show up at gala events. He annoyed the media by persisting in using his Park Slope gym for his daily workout and holding meetings at the small restaurant he liked in the old neighborhood.

The ill wind carrying the snow during his first month in office never really stopped blowing its mild, steady streak of bad luck.

In a uniquely de Blasio moment, he dropped the hero of a Groundhog Day photo op at the Staten Island Zoo. The animal fell to the ground and died a few days later, a fact that the zoo tried to cover up. But the cover-up made the minor fiasco a much bigger story than it should have been.

In 2016, he couldn’t endorse Bernie Sanders without provoking the Hillary campaign, but he believed in Bernie too much to let go of the dream. By the time he finally came around and did what he had to do, endorsing his former boss, the Clinton campaign was mad at him for the delay.

Yet Benjamin Kanter, currently a legislative aide of Assemblyman Simcha Eichenstein, remembers the mood around the mayor differently. Kanter, who started out as part of the mayor’s photography corps, found — and still finds — the mayor to be eminently likeable.

“He would tease us like friends,” says Kanter, who remembers working in a conference room in the basement of City Hall. “When staffers made inevitable mistakes, he handled it graciously. He’s a fine person. The mayor would stop in, just to say hello. It was unusual for a politician, and we all appreciated him.”

Within New York’s Orthodox Jewish community, de Blasio continued to be appreciated. He repealed Mike Bloomberg’s law forbidding metzitzah b’peh and continued to stand tall in the fight against BDS.

“Of course the mayor is not an anti-Semite,” says David Greenfield, who worked closely with de Blasio for close to 20 years as a politician and now serves as executive director of the Metropolitan Council. “He moved with his people, but at the same time, he stuck his neck out for our community and its needs several times. I think the City Council changed, New York changed, and he adapted to his electorate. It’s become very left.”

That shift leftward made it seem like de Blasio’s national moment might have arrived, as progressive voices were breaking out from beyond the ivy-covered campus walls and into the streets of America. Policies and politics once considered radically and impractically leftist were now being discussed by presidential candidates with a real shot at winning. It seemed natural for the progressive mayor of the biggest city in the country to lead the conversation.

Yet the bad luck continued, following him on the big day he went to launch his presidential bid.

Planning to show who the real boss of New York was, he was standing in front of Trump Tower, set to announce a new energy law. But a sudden thunderstorm forced him to take his show inside the public atrium, where the Trump faithfuls were waiting, riding the escalators behind him with signs that said, “Failed Mayor.”

The train never righted itself. New Yorkers perceived his candidacy as tone-deaf, that he was ignoring his duties to them in order to chase an unrealistic dream.

But never did the mayor of New York face a rougher spell in office than over the last three months. And this time, it was the Orthodox community, with whom he’d walked hand in hand for so long, that he lost in the process.

During the winter of 2019 and into 2020, the Jews of New York faced a concerning uptick in anti-Semitic attacks. Jews in Jersey City and in Monsey lost their lives. Community leaders, especially in Crown Heights, where incidents of unprovoked street violence against Jews had escalated, asked for an increased police presence.

Some felt that City Hall was unresponsive, though other veteran activists say that de Blasio did come through.

“We needed it most on Shabbos, and there were police everywhere on Shabbos,” says a Crown Heights community leader. “During the week, people have cell phones, so if they see something that looks suspicious, they can call.”

But beyond that, dispatching police isn’t as simple as it sounds.

“When the mayor and the NYPD trust each other, the citizens gain, and when they don’t, everyone loses,” the community leader explains. “Right now, the relationship isn’t great. The mayor doesn’t just press a button to send police cars.”

It was already a tense time. Then came COVID-19 and mayors everywhere, governors everywhere, faltered. No one was sure what was actual data, what was speculation, or how to fight an enemy you can’t even see.

But New York City was the eye of the storm.

Into mid-March, the mayor was still downplaying the virus, urging people to get on with their lives. Today, loyalists claim the mayor was being strong-armed by Governor Cuomo, with whom he has a complex relationship, but regardless, both Cuomo and de Blasio would end up looking very bad, and very petty, for their internal jostling as the virus killed tens of thousands of New Yorkers and sucked the life out of its economy.

There was fear, frustration, and blame, much of it directed toward the mayor. Soon enough he changed course, urging people to follow guidelines and shelter in place.

Then Rav Chaim Mertz passed away.

He Lost Them

It was late April when the venerated Rebbe of Tolaas Yaakov in Williamsburg was niftar, and hundreds of chassidim filled the Williamsburg street in order to pay their final respects, in a funeral that was initially coordinated with the NYPD. With such a crowd though, the social distancing became difficult to maintain.

“Something absolutely unacceptable happened in Williamsburg tonite: a large funeral gathering in the middle of this pandemic,” de Blasio tweeted. “When I heard, I went there myself to ensure the crowd was dispersed. And what I saw WILL NOT be tolerated so long as we are fighting the coronavirus. My message to the Jewish community, and all communities, is this simple: The time for warnings has passed. I have instructed the NYPD to proceed immediately to summons or even arrest those who gather in large groups. This is about stopping this disease and saving lives. Period.”

“To be clear, the people who joined the levayah were wrong,” says Yaacov Behrman. “There is no justification for their behavior, but the mayor was absolutely wrong for profiling the Jewish community.”

Pinny Ringel says that his boss apologized the next morning at a live news conference. “He didn’t hide behind a tweet — he looked at the cameras and apologized. I understand the anger about the tweet, but the pressure was tremendous and he reacted. You don’t throw out a 20-year relationship because of that.”

Even those who inclined to forgive the mayor took a dim view, when, the same day, tens of thousands of New Yorkers packed into parks and other locations to watch the Blue Angels air show, and when, weeks later, playgrounds in Boro Park and Williamsburg were still closed, while public parks were open throughout the rest of the city.

“That was a lie, of course it was a lie that the Jewish community was singled out,” says a senior city official. “It’s the sort of thing the frum websites post in order to get you to click. Playgrounds aren’t parks. Central Park was open, parks were open, but no playgrounds were open in any of the five boroughs. It wasn’t just Boro Park and Williamsburg, like they would want you to believe. All playgrounds, in all boroughs, were locked.”

Whatever the greater context, the optics were terrible: The media posted photos of wide-eyed Orthodox children standing hopefully near the locked playground gates, forbidden access to the rare patches of green in their concrete neighborhoods. Then, to complete the perfect storm, came the George Floyd protests and the subsequent anti-police uprising.

The mayor, long proficient at waiting to pick a side and then losing both, did it again.

Images from the streets were frightening. Along with the legal protestors, there was wanton looting and destruction, a forced curfew giving the city the feel of a war zone.

“If you know Bill de Blasio, you know he was haunted by the Crown Heights riots. It was happening all over again,” says one of his close people, “so of course, he initially backed the police. He wanted it shut down. He wouldn’t make the same mistake as Dinkins.”

But the mayor fumbled, defending police officers who appeared to drive their cars into a crowd of protestors. “If those protestors had just gotten out of the way, and not created an attempt to surround that vehicle, we would not be talking about this situation,” he said.

It was the wrong message at the wrong time for the wrong population. Thousands of young people crowding the streets of the city, progressives who’d once looked to him as their leader, were irate.

“De Blasio resign!” they cried and shouted and tweeted when he tried to take his place among them.

He couldn’t understand how he was the enemy. He was one of them. He’d also once protested. He’d even been arrested. Now he had a chance to change history for them but somehow, they’d stopped looking at him.

“The mayor,” says a colleague, “forgot that he wasn’t a radical college student living his best life, but the mayor. His job isn’t to be an ideologue, but to run a city.”

The protests went on, and the playgrounds remained locked. At least New Yorkers agreed on a subject of mutual dislike: As de Blasio the liberal protestor was rebuffed by New York’s impassioned leftists, de Blasio the playground-closer was demonized by some members of the conservative-leaning Orthodox community.

It seemed laughable that a few kids on a swing set were more dangerous than thousands of people crowding squares and bridges. Some community members decided that they had enough of what they termed outright hypocrisy. They declared open war on de Blasio and arranged a protest complete with a chain-cutting ceremony to reopen the playgrounds.

“I didn’t think that it was effective, even if the mayor was wrong,” says Yaacov Behrman, who isn’t defending the mayor’s policies either. “I love the elected officials who went to that playground, Simcha Felder, Kalman Yeger, Simcha Eichenstein. They are good men who really care about our community, but breaking the law sends the wrong message. We want to be examples and teach our children to follow the law even when you don’t agree with the law. File a lawsuit if you disagree, but don’t break into public parks.”

Former city council member David Greenfield has his own take. “Come on, do you really think you complain and make a difference through a viral WhatsApp video? Through kvetching? We literally had a chance to make a difference this week. There were elections. Guess what? Boro Park and Flatbush showed the lowest turnout in the city.”

The anger at the mayor is legitimate, he feels, but pointing fingers isn’t appropriate and calling him an anti-Semite isn’t just a lie, it’s also silly, “because if you’re going to waste it on him, what term will use when you face a real anti-Semite?”

Brooklyn legislators say that the day after the parks were forcibly opened by local politicians and activists in defiance of the mayor, Bill de Blasio quietly did his part to find additional funding for Brooklyn mosdos who’ve been suffering as a result of the virus.

“It was as if it we were back to the best days of the mayor’s relationship with the Orthodox community,” says an activist for the school, “and that tells you something about him.”

“You know,” says another administration insider, “in a relationship, there are rough patches. A marriage or business partnership is not without difficult moments. This wasn’t a great stretch, but look at all that we’ve done together.”

Yochonon Donn says that the mayor not being an anti-Semite doesn’t mean he’s been a great mayor. “As an Orthodox Jew, I would have a hard time coming up with reasons to hate him. He canceled Bloomberg’s metzitzah b’peh rule, and he was great — great — on yeshivos, changed sanitation schedules so as not to interfere with morning bus schedules, and eased pre-K rules to allow yeshivos to participate.

“But then you look at the broader picture and you think, there’s something very wrong here. The annual budget grew from $72 billion to $96 billion in just seven years. Police don’t feel safe tackling the bad guys, and the Jews are the first to suffer from that insecurity. People don’t feel safe walking the streets, and the mayor is giving press conferences touting the lowest crime records in history.”

That’s the tragic story of Bill de Blasio: good guy, great political operative, but a mayor who had a hard time pulling it all together.

Luck and timing were never his friends, and now they’ve joined forces to threaten his legacy.

“He still has time to save his legacy, and make a lasting impact,” says Yaacov Behrman, “so I wouldn’t write him off yet. New York is facing grave threats, and de Blasio holds the keys to prevent the city from becoming lawless and ruined.”

Speaking tongue-in-cheek, a close friend of de Blasio points out that New York’s embattled mayor changed his name once before.

“When he was 18, he went from being Warren Wilhelm Jr. to being Bill de Blasio. The person means well, but the brand is in trouble. Maybe he should change his name once more and try again?”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 817)

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (5)