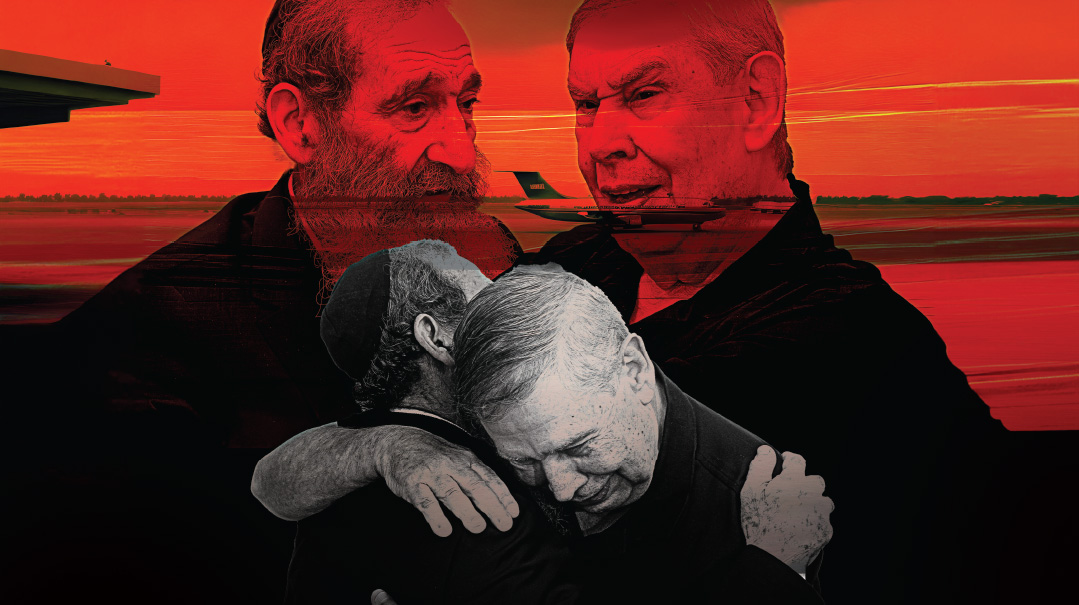

In the Driver’s Seat

Ten years after the passing of Ohr David Rosh Yeshivah Rabbi Chaim Moshe Flom ztz”l, talmidim and family members share who their father, rebbi, and mentor really was

(Photos: Family archives)

I

t was a hot Pesach Sheini in Jerusalem, 2008, and Sholom Waldman desperately needed a cold drink to stave off dehydration. The air felt oppressive and bleak as he returned from the levayah of his beloved rebbi, Ohr David founder and rosh yeshivah Rabbi Chaim Moshe Flom. As he made his way through the bus, clutching a bag with a cold bottle of soda and a few plastic cups he had managed to buy before getting on, he found a place to sit. With the hespedim still echoing through his mind, the thought struck him: “What would my rebbi have done with this bottle?” In a letter that he penned to the family after the shivah, he wrote, “I turned to the passenger next to me and offered him a drink. I was zocheh to provide cold, refreshing drinks to six passengers. Then I ran out of cups….”

Pesach Sheini is a timeless reminder of the desire to do more, the drive to take advantage of second chances and not get bogged down by missed opportunities. Rabbi Flom’s daughter, Malky Aharon, stresses the apt correlation. “Pesach Sheini was instated for Yidden who had missed the official calendar date for the Korban Pesach, and who, nevertheless, didn’t want to lose out on the mitzvah.” Indeed, Rabbi Flom’s entire life was one long pursuit of flash-by opportunities, a constant desire to grab more Torah, more chesed.

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Dr. David and Mildred Flom, Chaim Moshe studied in his early years in Hillel Academy, and encouraged by his teacher Rav Yehoshua Cohen, went on to continue his studies in Baltimore’s Ner Israel. Then, when the Yeshivah Gedolah of Pittsburgh opened its doors, he enrolled as its very first student.

When the time came for him to move on to Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim — where he became a close talmid of Rav Henoch Leibowitz ztz”l — he did so only after receiving the Pittsburgh Rosh Yeshivah’s assurance that a special shiur would be started for bochurim who were not planning on staying in yeshivah long-term. This was the first of many shiurim that would ultimately live on as part of his legacy.

As a boy of seven, young Chaim Moshe was severely injured by a blow from a golf club, leaving him with only one eye for the rest of his life. And yet, according to those who were close to him, the consensus was that the missing eye was a non-issue in his life. He functioned fine without it, and never complained. More remarkable, however, is how for a man with such restricted eyesight, looking outward became one of his defining qualities.

Following his marriage to Hindy Kurtz, and after a two-year stint in the Chofetz Chaim kollel in Israel, Rabbi Flom, then just 29 years old, decided to open a yeshivah — because for someone as giving as him, learning Torah for his own benefit was never enough. It had to be Toras chesed; it had to benefit others. His wasn’t to be another prestigious academy, but a yeshivah for American boys who weren’t exactly part of the yeshivah mainstream, who needed a place that would help them grow.

Rabbi Yosef Granovsky, co-founder of Yeshivas Ohr David together with Rabbi Flom and its current rosh yeshivah, first met Rav Chaim Moshe when they were students in the Jerusalem branch of Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim, back in 1972. “He understood that many of the American bochurim who came to study in Eretz Yisrael weren’t adapting well to the regular yeshivah settings,” says Rabbi Granofsky of his long-term partner. “He maintained that a yeshivah catering to their unique needs would give them a chance of success in the Torah world. We were both eager to help these boys develop into bnei Torah. We worked together for 20 years, but we never argued. If there was any disagreement, we approached our joint rosh yeshivah, Rav Henoch Liebowitz, for answers.”

With all the choices of out-of-the-box environments available today, it’s hard to imagine a yeshivah landscape barren of similar projects. But back then, Rav Chaim Moshe recognized the need and was determined to put it right, although others with whom he shared his vision weren’t convinced it would work. There were plenty of dissenting voices, and almost no practical sources of support, but he forged ahead and Ohr David has since become a memorable home to hundreds of talmidim who flourished there. Despite all the competition that has opened since then, and despite Ohr David remaining a small, nurturing kind of environment, never registering more than 50 bochurim at a time, the yeshivah today is as strong and vibrant as ever.

When probed for the secret of Rabbi Flom’s success, Rabbi Granovsky answers simply, “He placed his trust in Hashem that He would help him succeed.”

Rabbi Flom’s son Dov remembers how one of the bochurim was embroiled in an argument with his parents, who weren’t enthusiastic about his staying in the yeshivah. “One morning,” he says, “the boy’s mother calls him up to say, ‘You know what? Do what you want! You can stay and learn if that’s what makes you happy.’ When he asked what had caused this unexpected change of heart, she said she had just watched a documentary about a teen who’d committed suicide after fighting with his parents.”

Another boy was deliberating whether to remain in yeshivah or not; he was still in the dorm on Succos when their madrich took them to a Simchas Beis Hashoeivah at the Mir. “For some reason, Rav Yitzchok Ezrachi singled out this bochur and danced with him for a whole quarter of an hour. It left such an impact that he decided to stay,” Reb Dov says. “And from then on, every time my father met Rav Ezrachi after that, he always thanked him again for having made such a difference to the bochur’s life. You know, my father was certain that Rav Ezrachi had no recollection of what he was talking about, but he felt the need to thank him anyway.”

“M

y father’s ultimate goal was to spread Torah,” says Yisroel Meir Flom, his eldest son, “and as such, it was important to him to stay in touch with his talmidim and follow up on their wellbeing. This was before the age of click-and-send.” After his petirah, the family uncovered a veritable treasure trove of unused stamps, from when Rabbi Flom still wrote his letters by hand. At the same time, they began receiving heartfelt letters from students the world over, who were now offering their deep condolences.

Before his marriage in 1978 and the couple’s subsequent move to Eretz Yisrael, Rabbi Flom had also taught for a year in Jersey City’s Rogosin High School and served as an eighth-grade rebbi in the Hebrew Youth Academy of West Orange, New Jersey, for another two. One of his Rogosin students contacted the family, saying he had kept in touch with his former rebbi all those years — and he was already 41.

The Rosh Yeshivah’s students weave a colorful tapestry of testimony, creating a portrait of an inspirational rebbi who was, first and foremost, a friend.

“More than once, I encountered people who told me they were very close friends of my father,” relates his son Menachem. “I’d never heard their name before and found that strange, until I realized this was a feeling that everyone who knew my father came away with.” Another talmid writes: “I remember the dinner of ’96. I gave him a shalom aleichem, and then he put his arm around me and made me feel like a million bucks.”

“My father truly loved his talmidim,” says Dov Flom emphatically. “On his trips to the US, he’d take the time to call every talmid he ever taught, starting with the first year.”

Yet he wasn’t aftraid to give mussar when it was called for either. Pinchas Avruch, a former talmid, recounts what happened in 1986, during the yeshivah’s second year in Ramot Gimmel. “The beis medrash, dining room, shiur rooms, and dorms occupied six apartments in two buildings, so we crossed paths with regular Israeli families all the time. Rabbis Flom and Granovsky frequently reminded us to be aware of the neighbors. After Pesach, the sun was out and the weather was warm, so guys went up to the roof to work on their tans during lunch break… and a couple of them, forgetting there were other families in the building, were less than careful about outward appearances.

“I don’t remember if the shmuess that Shabbos was about tzniyus or gadlus ha’adam or what, but I clearly remember the way he said it: ‘Men, if you want to go to the roof to tan, that’s fine. But you need to wear a robe on your way up. Men, you can’t go up to the roof looking like you’re on the beach…’

“There was never a question that he loved you as if you were literally one of his own children, and he always found a warm, receptive way to address any issue. Any hadrachah he gave was given so gently and with such warmth and care, you couldn’t help but be receptive.”

And then there was Rabbi Flom’s trademark humor. He frequently schlepped the boys out of bed each morning with a joke.

“He would often start his shiur with a joke to catch our attention. His infectious laugh would get us all laughing, even if the joke wasn’t all that funny,” says Sholom Waldman. “Our shiur was the envy of the yeshivah.”

For a while, Rabbi Flom taught in a more “modern” seminary, and one of his former students there told the family she always liked his shiur best. “The other teacher made use of every second verse to prove how important it is to eliminate our enemies,” she said. “Your father made use of every other verse to teach us how to be a better person.”

And chesed wasn’t just words. When one of his roommates back in Ner Israel couldn’t sleep through the night because of his asthma, he didn’t hesitate to wake up Rabbi Flom and tell him he had lost his inhaler. Rabbi Flom got up, got dressed, and went out to find a pharmacy that was still open.

One talmid from Ohr David remembers the time when the kitchen worker didn’t turn up on a Sunday morning. “The sink was overflowing with dishes, cutlery, and dirty pots from Shabbos,” he remembers. “Rabbi Flom steps into the kitchen, takes in the scene and immediately flips his tie, rolls up his sleeves and begins to scrub… There was no task too demeaning for someone who loved his yeshivah and his talmidim so much.”

“His entire life, my father believed that losing his eye had been a miracle in disguise,” says his son Dov. “He had been told that due to the emergency surgery carried out to remove the injured eye, the doctors had discovered a life-threatening tumor right behind it, just in the nick of time.

If so, then his own ingenuity in performing chesed was one way of giving back.

For years, Rabbi Flom would approach poor families in the neighborhood, saying things like, “By mistake, I bought far too many tomatoes/cucumbers/apples this week. Would you do me a favor and take some off our hands?” It was a mistake he never seemed to grow out of.

Walking down the street in Geula one day, he caught sight of a traffic officer placing tickets. Quickly, he rushed around pushing coins through slots in the meters wherever he saw that the time had run out.

Rabbi Flom really saw people. He noticed them. He made it his business to pay attention to their needs. Strangers. Secular Jews. Even gentiles. With his one eye, he enjoyed the widest field of vision.

His son Yisroel Meir relates how on one of his fundraising trips to the USA, when every minute was precious, he heard of another person whom he didn’t know personally, who was also facing surgery to remove an eye as a result of a cancerous tumor. Apparently, the man was taking it very hard — and for Rabbi Flom that could only mean one thing. He dropped everything and traveled over an hour away, in order to visit this stranger and offer him chizuk.

On another transatlantic flight, he saw a mother traveling alone with a little baby. Graciously, he approached her, saying, “You know, I don’t usually sleep on flights. Would you like me to hold your baby so you can get some rest?” And for the next few hours, Rav Chaim Moshe paced the aisles with an unknown baby, patting it on the back and keeping it happy, so the mother could sleep. When he returned the baby, something prodded him to ask the woman how she was faring. Sounding frustrated, she let on that she was moving abroad and had left her husband behind. Rabbi Flom understood from her that she had no intention of asking for a get. As soon as he returned home, he got in touch with her again and convinced her to follow through with a halachic divorce.

His son Dov remembers how he was once hospitalized as a child. A Muslim boy lay in the bed next to him and Rabbi Flom greeted the boy’s father cheerfully. “You know him, Abba?” he asked his father, amazed. “Sure,” Rabbi Flom replied, “He fills our tank in the gas station near our home.”

In 2007, Rabbi Flom was diagnosed with an aggressive brain tumor. “There was another patient receiving radiation who wasn’t religious,” his daughter Malky recounts, “and he convinced her to light Shabbos candles. But he didn’t stop there. He asked one of us to go and purchase a pretty candle-lighting prayer so that she might be tempted to use it regularly.”

After his petirah, Rabbi Flom’s talmid, Sholom Waldman, wrote: “When he was undergoing treatment he told me that despite intense yissurim, the part that bothered him the most was that he had to become a taker for the first time in his life.”

P

erhaps one of the most remarkable forms of chesed that Rabbi Flom was known for was the running of his “Flom-mobile.” His wife recalls how they were zipping to the hospital for the birth of one of their children, when she told her husband, “No stopping at bus stops this time!” and he looked so devastated, she almost changed her mind.

“Seeing my father return home saddened when he hadn’t found anyone at the bus stop to give a ride to, made me think he was like Avraham Avinu — upset when he didn’t have guests,” says his daughter Shira, his eldest child. “Chesed energized him.”

“There was a bus stop right opposite our house in Sanhedria Murchevet,” explains Dov Flom. “My father wouldn’t start the ignition without first checking to see whether anyone needed a ride. At some point all the bus stop regulars knew him.” Rabbi Flom perfected giving people rides into a fine form of chesed. “If he took down the garbage, he wouldn’t go to the dumpster without first walking by the bus stop to check whether there wasn’t anyone waiting who needed a ride.”

And the car that so faithfully served its purpose? It was a 22-year-old Subaru.

“We figure what kept its engine running was pure, refined, chesed gasoline,” Dov continues. “My maternal grandmother, his mother-in-law, lived in Talpiot, and he’d drive there often, taking the long route. When someone asked him why he didn’t drive the shorter route, he answered that driving through the other route meant he would have to pass a bus stop where Arabs often waited and due to the security situation he couldn’t give them rides. ‘So just drive by! Don’t stop!’ we’d tell him, not understanding what the problem was. But our father shook his head, saying ‘I can’t do that. I just can’t drive by a bus stop without offering rides….’ ”

Everyone in the neighborhood knew him as the man who gave rides. At the shivah, when his son Yisroel Meir began describing his renowned penchant for stopping at bus stops, one visitor objected.

“Rabbi Gewirtz a”h interrupted me and said, ‘Don’t sell me lokshen. All those rides were just a camouflage for who he really was…For years we’d meet up Pesach time at Kerem B’?avneh yeshivah, [where he family spent Pesach], which has a huge otzar seforim. No matter what hour of the day or night it was — whenever I’d enter the yeshivah’s otzar seforim, I’d find him with his nose in a sefer, learning b’?yun… and this was his vacation!’ ”

Sholom Waldman recalls how Rabbi Flom would hold a party, replete with rugelach and bourekas, after every completed perek of Gemara. “I asked him why he made such a big deal for finishing a perek, and he said that really, every page of Gemara warrants a party. ‘But if you throw a party too often,’ the Rav explained, ‘the celebration loses its effect….’ ”

“The strongest memory I have of my father,” recounts Rabbi Flom’s daughter Shira, “is that no matter what hour of the night I’d wake up, I’d find him sitting in the living room learning.” It is a memory that every one of his children holds dear. “We’d see him learning through the wee hours of the night,” says Malky Aharon, the youngest. “He’d go to bed and ask me to wake him in ten minutes, so he could get back to his learning. Sometimes, I’d urge him to let me give him a quarter of an hour, and he’d give in.”

Needless to say — anyone who enjoyed a ride in the famous Flom-mobile was automatically treated to a gevaldig vort on the way. It was part of the deal.

“Every vort my father heard, he made sure to put in writing,” says Dov Flom. “He’d fill up piles of index cards, which he kept in a drawer, and he’d share a precious vort with anyone he met. At some point, he began sending out weekly emails to all his talmidim with the vort he heard that week that he’d enjoyed the most.”

To a few of his children, Rav Chaim Moshe confided that, more than anything else, he wanted to have his health back so that he’d be able to see his children grow in learning.

“Several years into our marriage,” recalls Shira, “my husband and I realized we had little choice but for my husband to get a job. On his way to an interview one day, he dropped in on my parents for a short visit and my father asked him where he was heading. When my father heard what his interview was about, he was deeply grieved by the fact that matters had reached such a point and he asked, ‘How much more would you need to be able to stay in kollel?’ My husband mentioned a sum, and my father answered instantly, ‘Okay, then. Consider it done!’ He found a donor for us who’d be willing to augment our income, and my husband went back to his shtender. Every month, he’d collect the extra sum from his rosh kollel together with the standard kollel stipend. Astonishingly, when my father passed away we found out that that very month was the month in which the agreement with the foreign donor came to an end! We also discovered that the sum donated by this donor didn’t completely cover what we had needed, and all those years my father had made up the difference himself without ever saying a word.”

Toward the end of his life, when he was no longer well enough to give shiurim in his yeshivah, a local bikur cholim organization by the name of Darkei Miriam offered to arrange a kumzitz for him in the Flom’s home, to keep his spirits high.

He asked his wife to tell them, “If you really want to make him happy, let him give a shiur first!” And they did. Every Thursday night, bochurim from Brisk came to sing and dance, and to hear a shiur from Rav Chaim Moshe.

Rabbi Flom’s final shiur was given at the beginning of Nissan. By then, most of the bochurim had flown home for bein hazmanim, and so Darkei Miriam sent their own volunteers instead. By the following morning, Rabbi Flom had already lost some lucidity — the tumor had gained the upper hand.

When news of his petirah spread round the globe, a great many friends and talmidim — friends who learned so much from him, as well as talmidim who also felt like friends — found it hard to absorb the news. When a man is so full of life and vitality, it seems hard to imagine him gone.

In his final letter, Sholom Waldman expressed this for everyone: “When the hespedim finished and they brought the niftar outside, I was zocheh to accompany the niftar a few feet, until the van drove off… taking my rebbi to his final resting place. As it disappeared from view, it hit me that I would never see him again.”

And yet, out of sight is far from out of mind. Since that week of shivah ten years ago, many students have stayed in touch, and Sholom Waldman as well as another talmid have named a child after their dear rebbi.

“I met an acquaintance on Pesach,” relates Dov Flom wistfully. “He saw me and said: ‘It’s been ten years, and no one picks me up at the bus stop anymore.’ ”

Because while most people pass by and let the bus drivers do their job, for Rabbi Chaim Moshe Flom, driving people to their destination and their destiny was never anyone’s job but his.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 707)

Oops! We could not locate your form.