Healthy at Last

We treated the infection again and again, but it kept returning

When my daughter Shevy was four years old, she came down with a fever. I wasn’t overly concerned, she didn’t seem to be in any pain, but my pediatrician decided to test a urine sample to rule out a urinary tract infection (UTI).

Surprisingly, the test came back positive and the doctor prescribed a round of antibiotics. I’d heard of childhood conditions that could affect the bladder so I questioned the doctor, asking if further testing was in order.

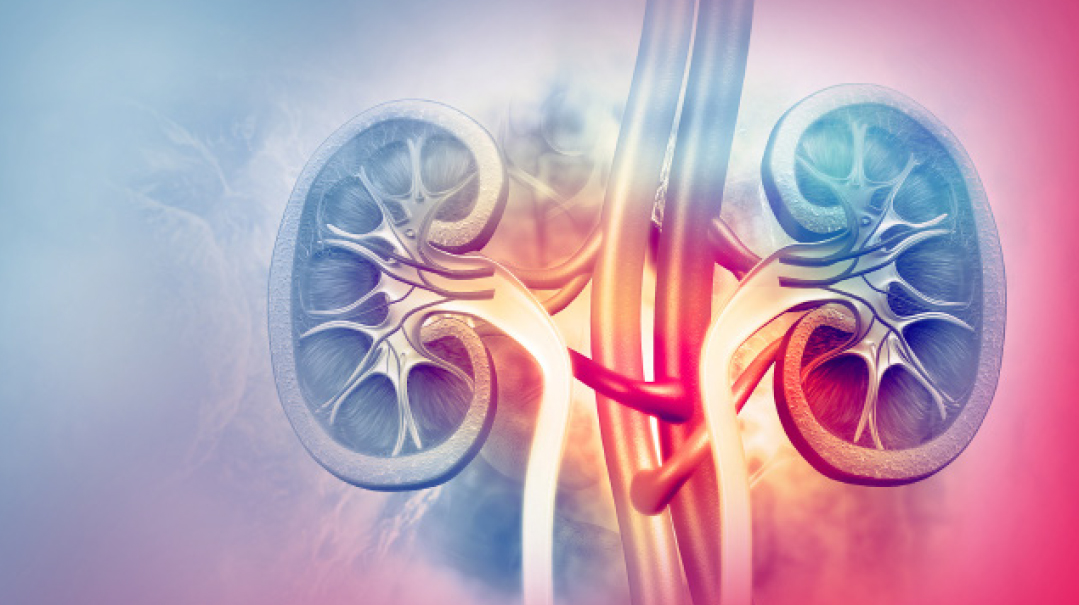

He reassured me that there was no need to worry about a one-time UTI. He went on to explain that conditions like vesicoureteral reflux (where there’s backflow of urine from the bladder to the kidneys) mainly affects infants within the first few weeks of life (presenting with a high fever) and is usually resolved by early childhood. As Shevy was already four, had never experienced a UTI, and rarely got sick, we had nothing to worry about.

Unfortunately, our relief was premature; that UTI was just the very beginning. Shevy continued to have UTIs over the next two years with alarming frequency. The cycle repeated itself over and over — the diagnosis of a UTI, a round of antibiotics, a brief period of calm, and another UTI.

When a urinary tract infection goes to the kidneys, which is what was happening in Shevy’s case, it’s excruciating, and comes with very high fevers, typically to the tune of 104°F. Watching our daughter suffer was horrible.

One Friday, I was waiting in the urgent care center with Shevy, who was yet again suffering from a UTI. It was getting close to Shabbos and an amazing friend called me and told me to go home, assuring me that she’d arrange for a private doctor to see Shevy. I let out a huge sigh of relief. We were living in Europe at the time and the medical system was difficult to navigate, so a private doctor seemed like a very good idea.

The doctor was patient and listened closely as we described the situation. He said that he’d promptly refer Shevy for further investigation of her recurring infections, something our pediatrician had refused to sign off on. He also explained that UTIs that reach the kidneys are hard to treat, and therefore, he was going to give me two prescriptions for antibiotics: one was dated for that day and the second for the following week.

He explained that some liquid antibiotics given to children lose their potency within a few days and it’s best to get a fresh bottle made for the second week of treatment. He sent his recommendations to our family doctor along with a referral for an ultrasound. Thankfully, the treatment worked and the UTIs finally subsided.

The ultrasound, however, confirmed that Shevy did indeed have vesicoureteral reflux and there was some scarring on the kidneys. I was devastated. I couldn’t believe the doctors had missed it for so long.

Oops! We could not locate your form.