Hard Truths about an Ancient Doctrine

Harold Rhode began his study of Islam nearly five decades ago. His prescription for the West? Never defend, never explain, and always go on the offense

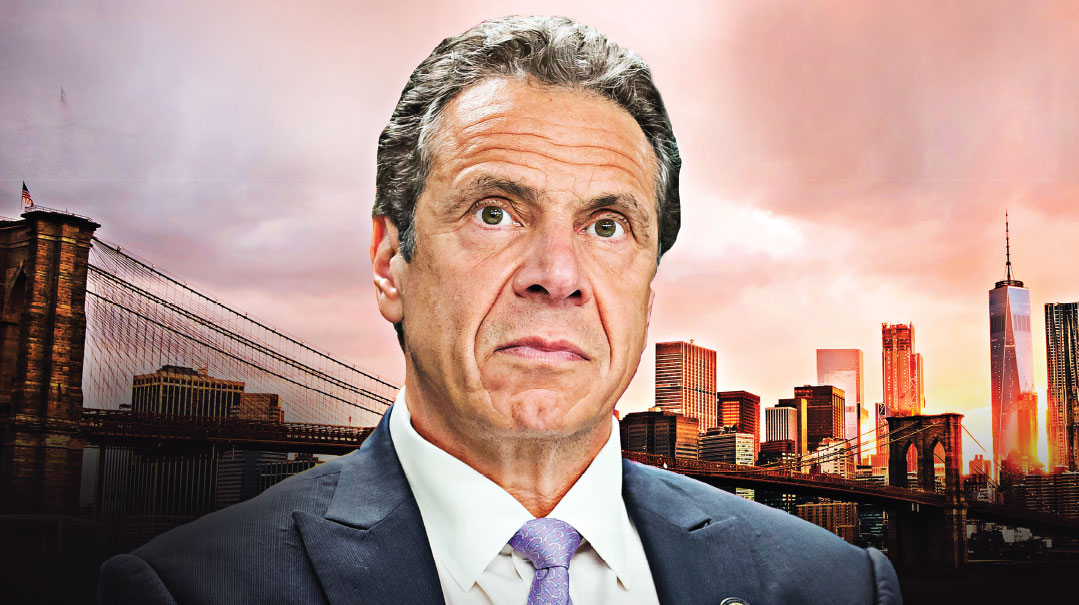

Because Muslims don’t see people as individuals but as members of groups, they reflexively support members of their in-group over any outsiders, whether it be family members over non-relatives, fellow members of their clan over members of another clan, or the Muslim nation over Christians. They also assume that non-Muslims apply this same calculus (Photos: Lior Mizrachi, Biosketch)

Last December‚ about two hours after President Donald Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, the media was in a tizzy. Pundits were breathlessly prognosticating that the White House move would ignite an explosion of pent-up rage on the Arab street.

Meanwhile, Dr. Harold Rhode went on the radio in Washington, D.C., to explain to a local audience that despite dire warnings to the contrary, he didn’t anticipate any violent outbursts from the Muslim world. Time proved the historian and Islamic affairs expert correct: Except for some staged skirmishes in the West Bank and boilerplate criticism out of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, the Middle East remained shockingly quiet.

“Jerusalem is only important to Muslims when non-Muslims control it,” Rhode says now, in conversation with Mishpacha. “Had that not been the case, Jordan would have proclaimed it their capital when it was under their control. For Sunni Muslims, the issue of Jerusalem is less religious than political, and for Shiites, it’s all political. Right now, the Muslim street, for the most part, is fed up with its leadership and is sick and tired of being taken advantage of by them for political purposes.”

If anyone could have predicted this outcome, it’s Harold Rhode. His decades of study and living among Muslims in the Middle East has attuned him to how the Muslim world thinks. Rhode received his PhD in Islamic history from Columbia University, specializing in the history of the Turks, Arabs, and Iranians. He studied overseas for years in universities in Iran, Egypt, and Israel. In the 1980s, he went to work as an advisor on the Islamic world for the US Department of Defense.

Rhode points out that Jerusalem has always been a focus for other nations, and today, the Palestinians are only part of the crowd. Turkey’s leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, issues harsh rhetoric about Jerusalem as a way of reasserting his country’s historic leadership of the Sunni world. And of course, the Iranian regime is obsessed with the Holy City. Harold says a prominent mullah admitted to him personally that according to Shiite tradition, Jerusalem belongs to the Jews. Why then this obsession? He says the ayatollahs hope to exploit the issue to gain dominance in the centuries-old conflict between Shiites and Sunnis.

“Iran, a Shiite country, is using Jerusalem as a tool against the Sunnis,” he explains. “Because the Sunnis, who cannot tolerate Jews running Jerusalem, have not been able to wrest Jerusalem from the Jews, the Shiites say they will do the job for them. For that purpose, the Iranians established Hezbollah and are empowering Hamas. Tehran believes that Israel’s inability to destroy Hezbollah during the 2006 Lebanon War showed the Sunnis that Shiism is the way.”

The entire geopolitical landscape shifted, however, with President Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. That announcement, Rhode says, dealt a severe blow to Tehran’s ability to assert itself within the Arab world, exposing it as weak. That, together with the president’s refusal to certify the Iran Deal, has terrified the Iranian government; they don’t know what’s coming next.

“For the last five months, Iran hasn’t attacked any US ship in the Gulf,” Rhode points out. “They haven’t attacked anyone. They are petrified, which is good.”

The Jerusalem issue has exposed deep divisions between the Muslim street and its leadership, but other internal struggles being played out within the Islamic world are of even greater significance to the West. Some more moderate Muslim authorities want to make their religion more humane, and want to offer a new interpretation of the Koran to advance that goal. They say the Koran’s earlier verses place a greater emphasis on peace and tolerance than the later verses, which call for jihad and holy war. However, these moderate voices have made little headway in privileging the earlier verses over the later ones.

“It was men, and not Muhammad or Allah, who decided that the later verses supersede the earlier ones,” Rhode says. “There are Muslims who adhere to the belief. But there are others who know that they are finished as a society if they don’t find a way to get along with us. Right now, many fundamentalist Muslims think they are winning the war with the West and feel emboldened by this.”

Rhode says it’s critically important for the West to understand that there is no room for compromise in this struggle. “The West must defeat them decisively for any dramatic changes in their worldview to take place. For Muslims, compromise means dictating what losers can and cannot do. At the same time, we must give them the space to re-interpret their sources. They can do it. But will they do it?”

arold Rhode arrived at these truths about Islam over time, but they were hard for him to accept, intellectually and emotionally. Since his early teens, he had been fascinated with Muslim society and convinced that open dialogue would resolve all its differences with the West. All it would take, his liberal mind assured him, is understanding and compromise. To help bring peace between the two societies was a goal he set for himself and for which he was prepared to dedicate his life. His plunge into Middle Eastern studies was motivated by this dream.

One positive consequence came out of his initial affinity with Islam’s G-d-centered outlook: He discovered Judaism. Now 68, Harold Rhode has been proudly shomer Torah u’mitzvos for over 25 years, which has “enriched my life in ways I couldn’t have imagined.” It has also helped him better appreciate the religious mindset in general — a mindset he believes is fundamentally incomprehensible to most secular societies.

He gradually came to understand that the chasm between the Muslim world and the West was just too vast to bridge. Muslims view themselves as engaged in an existential spiritual struggle, while the Western liberal elite nurtures an inability and unwillingness to accept that another part of the world thinks differently about spiritual matters. This conundrum gradually led Rhode to shift his focus: Rather than build relations and mutual understanding, he now wants to protect the West from Muslims. Jews are particularly vulnerable in the current confrontation, since most Muslims do not distinguish between Israel and Jews.

Rhode brings a perspective to this struggle that not many in the West possess. After the 2003 Gulf War, when he was on staff with the Office of the Secretary of Defense, he served as a liaison with the Coalition Provisional Authority in Baghdad, advising on how to understand and negotiate with Turkey, Iran, and Arab and Central Asian countries.

In that role, he came to world attention as the rescuer of a cache of Iraqi Jewish holy books and artifacts discovered in the flooded basement of Saddam Hussein’s intelligence headquarters, which came to be known as the Iraqi Jewish archives. Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld had these waterlogged materials whisked to the US, where they were cleaned, repaired, conserved, digitized and exhibited.

Rhode’s other claim to fame is his close personal relationship with famed Islamic historian Dr. Bernard Lewis, whom he calls “Uncle Bernard.” He continues to visit the nearly 102-year-old scholar regularly.

Rhode continues sharing his insights through international news media such as the Wall Street Journal, and delivers lectures worldwide — he was recently in Beijing. He also authored the recently released book Modern Islamic Warfare: An Ancient Doctrine Marches On, on how Muslims think about the world. His conclusions pain him.

“To combat militant Islam, we have no choice but to be prepared at all times to go on the offensive, whenever they present us with a new problem with which we must contend,” he advises. “Never defend. Never explain. Always be on offense. Our only alternative is to obliterate each new attack before the small fire turns into a forest fire and destroys the entire landscape.”

For Harold Rhode, the cracks in his idealistic plan to bring peace between Muslims and the West first began to appear in 1973, when he was 23 and studying Arabic and Islamic history at the American University of Cairo. His primary intention in enrolling in this program — some of its American professors were anti-Semitic — was to get to know Muslim society on a deeper level. He befriended many Muslim students at the university, communicating with them strictly in English. Although he was already fluent in Arabic (he also speaks Turkish, Persian, Hebrew, French, and some Spanish and Italian), he kept that a secret from his fellow students, so he could learn what was really on their minds when they talked to one another.

His newfound comrades graciously welcomed this Jewish kid from a predominantly black neighborhood in Philadelphia into their homes and mosques. Although they were friendly, Rhode began noticing something curious about the vast majority of Muslims he met. Whether educated or uneducated, they all appeared to be immune to empirical evidence; they also displayed disregard for thinking through ideas logically. As hard as he tried, he found himself utterly unable to dislodge them from believing in outright fantasies they held to be true, no matter what proofs he brought to the table. Objective truth fell by the wayside so they could preserve the delusion they concocted about the world.

“Westerners understand that there are different narratives about a given situation,” he says. “As long as people back themselves up empirically, we are willing to consider and respect their perspective. That’s not the case in the Middle East, where most people only accept one narrative, their own — everyone else’s narrative is wrong, regardless of objective reality. I soon realized that truth didn’t matter there and was easily discarded for the point they wanted to make. Good friends often looked me in the eyes while lying to me.”

Rhode gives an example about a fellow student named Ahmad. Asserting that his having grown up in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City gave him the ability to immediately identify any Jew, Ahmad insisted that Rhode, with his olive complexion, could not be Jewish. He surmised that Rhode must instead be Jordanian, Lebanese, or Palestinian. Harold was shocked. He tried to dissuade Ahmad of this, but the Arab student declared that all Jews, as descendants of European converts, were blond-haired and blue-eyed.

Rhode interjected that Ahmad had been only one year old when the Old City became Judenrein following the 1948 War of Independence; therefore, it was impossible for him to have met any Jews.

“When I pointed this out to him, he thought I was crazy,” Rhode recalls. “ ‘Why then do they call it the Jewish Quarter?’ Ahmad asked. Given his worldview, he couldn’t imagine that I might be Jewish. He could not accept that my ancestors were, in fact, from Europe.”

Harold, a brilliant scholar in his own right — he graduated with a BA in Islamic studies at the age of 20 — found this deeply troubling. It gnawed at him; still, he remained optimistic. “I wasn’t smart enough to recognize the ramifications of this way of thinking that, as a society, Muslims created fanciful narratives for themselves and refused to see things as they were. It took me a few more years to understand its implications more fully, which included living through trying times, as well as the early and middle stages of the Iranian revolution.”

Somewhat more skeptical (albeit still idealistic) Rhode encountered an entirely different sector of the Muslim world when he came to study in Iran a few years later. Iran was a proud and ancient urban civilization and light years ahead of other Muslim countries in terms of culture and sophistication. It hit him immediately on arrival in Iran that the Shiite Islam practiced there was not the Islam he had come to know.

The intellectual atmosphere among the Shiite elite in Iran, and later in Iraq, was stimulating and dynamic. At first, he couldn’t quite grasp the reason for this. Was it because he was older and better able to articulate his ideas? Locals in the know told him this ability to think analytically and critically developed as a survival tactic: As a persecuted minority swimming in a Sunni sea, Shiites were forced to keep a few steps ahead of their tormentor — something Jews could identify with, given their history of persecution.

“The Sunnis have been trying to impose their will on all of the non-Sunnis from time immemorial,” Rhode says.

Moreover, the Shiites never accepted that the gates of critical thinking and independent reasoning closed after the seventh century. They also utilize the Talmudic method of analysis to get to the truth. Shiite mullahs, Harold says, are fascinated with the Talmud, and they study it regularly. One Shiite mullah quoted to him verbatim from Bava Metzia.

Unfortunately, since the 1979 Iranian revolution, Rhode noticed a sharp decline in empirical, analytical thinking among the religious elite of Iran. Rather than pursue religious studies, their brightest young stars go into business or government. The less capable study religion, which has resulted in Shiite law and ideology being fundamentally altered to further their leaders’ political ends. “Sadly, the traditional Shiite establishment has been destroyed by the Iranian government, which has politicized Shi’ism to such an extent that most of the Grand Ayatollahs reject much of the Iranian government’s decisions, but cannot say so publicly for fear of being imprisoned or assassinated by the regime.”

Common to both Shiite and Sunni Muslim societies is an orientation toward shame as means of enforcing cultural norms, rather than guilt. Muslims are expected to behave in a highly regulated way and are kept in line with the fear of being publicly shamed in front of the group. Western societies, on the other hand, privilege the individual rather than the group; guilt and anxiety are the internal mechanisms used to enforce society’s rules and expectations. Westerners self-regulate with the inner gyroscope of the values instilled in them by family, school, and community, according to sociologist David Riesman.

Muslims, on the other hand, are much more worried about how others think of them as members of a family or group. As a result, they don’t know themselves well enough psychologically to see themselves as individuals who can shape their destinies beyond the group unit. Consequently, they carry a massive psychological burden.

“The concepts of honor and shame are paramount to the Muslim mentality, concepts that are alien to most of us,” Rhode says. “In Western societies, teenagers may rebel against their parents, but with maturity, hopefully, they come to understand that their parents have what to teach them based on years of experience. In the Middle East, the underlying mythology is different. The child grows up, revolts against the father, and the father kills the child. Teenagers may be fuming inside, but there is no way for them to express those feelings. Doing so risks dishonoring the family. As a result, they are constantly sitting on a powder keg of anger. Over the years, I’ve witnessed many fathers publicly shame their sons. My heart went out to these kids when that happened.”

The idea of “let bygones be bygones” is also nonexistent. Justice, as Westerners understand it — or mercy, for that matter — don’t apply. Within the Muslim lexicon, concepts only apply between G-d and man.

“They bomb their schools, mosques, and hospitals... look what they’re doing to each other in Syria,” Harold says. “The concept of balance replaces justice. Families and tribes must keep their relationships in balance. In practice, that means that if someone kills someone from another family or clan — accidentally or otherwise — family members must avenge that death, even if it takes generations. Anyone from the other social unit is fair game. Muslims are taught these beliefs from early on.”

Because Muslims don’t see people as individuals but as members of groups, they reflexively support members of their in-group over any outsiders, whether it be family members over non-relatives, fellow members of their clan over members of another clan, or the Muslim nation over Christians. They also assume that non-Muslims apply this same calculus.

This belief is cultural and not religious. Harold once met an Iranian Communist accompanying his religious mother on a pilgrimage to the holy city of Qom. In the course of their conversation, the issue of the Lebanese civil war came up. The Iranian, as a true Communist, said he could only support the impoverished Shiites in the conflict who were being exploited by wealthy Christians. When Rhode pointed out that there were wealthy Muslims who likewise exploited impoverished Christians, the Iranian Communist looked confused.

“But we have to support our Muslims brothers,” he replied.

These old issues of balance and supporting one’s group influence the relationship between Shiites and Sunnis. Their feud concerning who will carry the mantle of Islam, which goes back to the beginning of the religion, remains a festering sore. Those Westerners who are tone-deaf or naive as to this dynamic will quickly find themselves entangled.

When President Barack Obama began his famous Cairo speech with the phrase “as-saalamu ‘aleikum,” a phrase Muslims use only to greet other Muslims, his audience understood his insinuation — that he too is Muslim. But when he gave in to all of Shiite Iran’s demands to finalize the nuclear deal, the Sunnis abandoned him.

“Despite Obama’s support of the Muslim Brotherhood and distancing himself from Israel, the Muslim world that is 86% Sunni saw him as a betrayer,” Rhode says.

As Rhode navigated his way through Muslim societies, all of this became strikingly clear to him, and all the more disturbing because it was gilded over by a veneer of warmth, hospitality, and charm. He can well identify with former CIA director John Brennan’s sentiments expressed in a 2010 speech at the Islamic Center at New York University, about being welcomed in Saudi Arabia “in a way that is a reflection of the tremendous warmth of Islamic cultures and societies.” Correct; and also dangerously disarming.

“Arab culture is attractive in ways that American and Israeli culture is not,” Harold says. “Our newspapers reveal all our warts. But internally, our societies are solid. In Arab societies, its people are very kind, very gracious and extremely hospitable, especially Iranians, who have perfected this art. I’ve found that many are the most charming, kindest, sweetest, and deadliest people I have ever met. They wowed Secretary of State Kerry. But the more you dig, the more you realize how diseased their societies are.”

(Elite Iranians are excellent chess players and are always eight steps ahead of their opponents. Rhode believes that Secretary of State John Kerry was severely outmaneuvered by them while negotiating the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.)

It took Rhode many years to recognize this for what it was. There were inferences, which he rationalized along the way; promises not kept; even accusations of spying for Israel.

“In retrospect, despite the friendship they offered me, I don’t think that most Muslims ever trusted me,” he sums up. “Most expected me to convert to Islam. Many couldn’t get their heads around the fact that I could be so knowledgeable about Islam, and yet not want to convert. For them, that was impossible.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 702)

Oops! We could not locate your form.