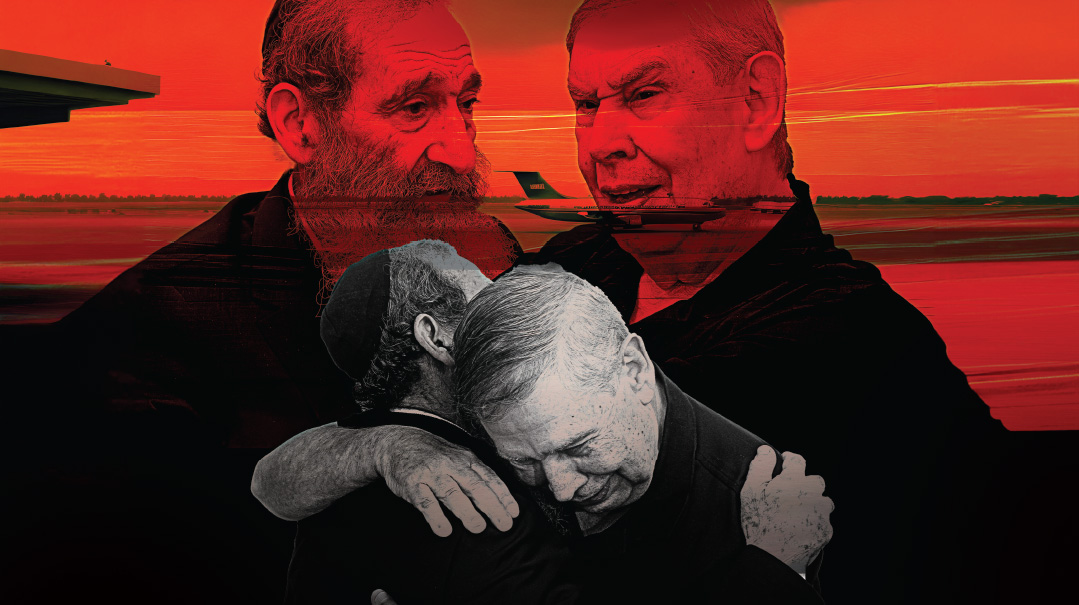

Every Child’s Heart

A side of Rav Yitzchok Scheiner ztz”l that many never knew

Rav Yitzchok Scheiner, the rosh yeshivah who went from a public high school senior in the 1930s to become the torchbearer of the great Kamenitz tradition, never kept his personal story a secret.

Rav Scheiner, who passed away last year at age 98, would often mention how one day in 1937, Rabbi Avraham Bender — a menahel of the Slonimer yeshivah in Poland turned emissary of New York’s Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok Elchanan — came to Pittsburgh and stayed with the Scheiners, Polish immigrants whose kashrus he trusted. There he met their teenaged son Isadore, who has just graduated from Peabody High School and was planning on going to college to study mathematics.

Born in 1922, Isadore was a regular American kid — an avowed baseball fan with an aptitude for math. His religious parents sent him by trolley car to an after-school Talmud Torah, but by the time he graduated high school, he was well on the way to vanishing into the great American melting pot.

But that didn’t deter Rabbi Bender, who, turning to his host, asked, “Why don’t you send your son to yeshivah?”

Mr. Scheiner, who didn’t know that there even were yeshivos in America, agreed to let his only son accompany Rabbi Bender to the yeshivah in New York.

Sixteen-year-old Yitzchok, as he became known then, joined Rav Moshe Aharon Poleyeff’s shiur in RIETS, and took to his learning with gusto. Two years later, he transferred to Torah Vodaath, where his rebbi was Rav Dovid Bender, Reb Avraham’s son. Yitzchok was an ardent Pittsburgh Pirates fan, but he once told how “In Rav Dovid Bender’s class something strange happened to all the American baseball fans. Our love of Torah eclipsed that of baseball. Rav Dovid taught his talmidim that the Torah is more important than anything else.”

A transformed young man, Yitzchok Scheiner became close to Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz and began attending the shiur of Rav Shlomo Heiman, Rav Boruch Ber Leibovitz’s prime disciple. And he also became a talmid of Rav Reuven Grozovsky, Rav Boruch Ber’s son-in-law.

When Rav Yitzchok made the long journey to Eretz Yisrael by boat in 1949, he carried with him a letter from Rav Reuven Grozovsky to Rav Reuven’s brother-in-law, Rav Moshe Bernstein, another son-in-law of Rav Boruch Ber. Rav Bernstein had just founded Yeshivas Kamenitz in Jerusalem, and his daughter Esther Leah was of marriageable age. The letter contained a simple message, the highest accolade a rebbi could give: take this bochur as your son-in-law.

Rav Scheiner eventually moved to Switzerland to serve as the rosh yeshivah in Montreux, but returned to Jerusalem following the passing of his father-in-law in 1956. He was just 34 at the time, but took the reins of the yeshivah, together with his brother-in-law Rav Asher Lichtstein.

Running a yeshivah in a poor city in a cash-strapped country was never going to be easy. Yet even in those early days, before Rav Yitzchok Scheiner was a household name, the special mixture of gadlus and caring made him a unique rosh yeshivah.

Rav Scheiner became recognized as one of the gedolim of the generation and was a member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah, but what many don’t know is that, as head of the Kamenitz institutions — which covered cheder through yeshivah gedolah — he was not only rosh yeshivah, but took personal responsibility for every single child under his umbrella.

Caring, Rav Scheiner understood, was at the heart of chinuch. And even though Kamenitz is a large institution, and he was the menahel of a cheder, yeshivah ketanah, yeshivah gedolah and a kollel, to him every single boy and young man was a yachid. Rav Scheiner’s pedagogical skills soon became legendary among the chinuch professionals of Eretz Yisrael.

But he wasn’t one of those loud, center-stage people whose presence screams out “expert.” In fact, he was one of the most self-effacing, humble and altruistic men around. One great-nephew, who had learned in Kamenitz as a bochur and spent time in the simple Scheiner home, was doing well financially and told Rav Yitzchok that he wanted to buy him an air conditioner as a gift.

“He and my great-aunt refused point blank to even consider my offer. If I had extra money, they told me, I should give it to the yeshivah,” he remembers. “Many families in Geula and Meah Shearim didn’t have air conditioning. But for someone who had grown up as an American to not only refuse to purchase an air conditioner but to turn down an offer to acquire one when it came his way, made a deep impression on me. That wasn’t the only thing that impressed me about the Scheiner home. Rav Yitzchok’s mother was my great-grandmother, and at that time, she was living in his house, and his mother-in-law was living in his house. Both elderly women were over one hundred years old, and both were being looked after by the Rosh Yeshivah and his rebbetzin, who were consistently at their service.”

Another great-nephew remembers a conversation the Rosh Yeshivah had with some guests who’d come to his home. The conversation turned to the Chofetz Chaim and the kind of house he lived in. One of the people there turned to Rav Yitzchok and asked, “You mean it looked like this? Like the Rosh Yeshivah’s dining room?”

“No, no,” Rav Yitzchok replied, taking in his own ascetic surroundings. “Not like this. The Chofetz Chaim really didn’t have any gashmiyus.” Years later, he allowed a portion of his apartment to be renovated — but only because he was dividing his tiny living space and giving part of it to one of his grandchildren, so the grandchild’s portion was fixed up.

Rav Scheiner, with his simple, humble, down-to-earth demeanor, was not only a master educator, but acutely familiar with mathematics, medicine, and the sciences. He was also extremely knowledgeable about OCD and other psychological afflictions that bochurim suffer from at times. One might not expect an elderly rosh yeshivah/menahel from Rechov Tzefania to know how to handle the kind of syndromes and conditions that had only been given public recognition in recent years. But somehow, he always did. He helped them, and knew when intervention was necessary, enabling them to carry on with their lives productively.

On the corner of tree-lined Rechov David, off Rechov Yechezkel, stands the Kamenitz cheder, around the corner from the Kamenitz yeshivah at 22 Yechezkel. When Rav Scheiner returned from Switzerland, he not only took over the yeshivah, but opened the Kamenitz Talmud Torah, and a few years later, the yeshivah ketanah. Rav Scheiner was now head of the Kamenitz institutions, serving as rosh yeshivah as well as making the policy decisions for the cheder. Together with his brother-in-law Rav Asher Lichtenstein, Rav Scheiner set out to build a cheder to the best of his considerable abilities, seeking out the people whom he felt would be able to carry out the mandate of a superior Torah education.

And he found them, one by one.

One of the cheder’s first principals was a talmid chacham by the name of Rav Yitzchok Shlomo Zilberman, who later created the famed Zilberman derech of learning and opened his own institutions (and was the famed “Yerushalmi” who managed to bring Israeli media icon Uri Zohar to teshuvah so many years ago).

Rav Binyomin Kohn is the current principal of Kamenitz cheder, and he had the privilege of working closely with Rav Yitzchok for many years, a relationship that deeply impacted his life. Reb Binyomin relates that he began working in the cheder during the years his own children attended. At that time, before he came aboard, there were certain things about the way the cheder was being run that made him unhappy, and since other parents felt the same way, they decided to call a meeting with Rav Scheiner and express their concerns.

A few days later, Reb Binyomin ran into Rav Scheiner, and got right to the point:

“Reb Binyomin,” Rav Scheiner said, “Why are you wasting your time with those kinds of meetings? If you really want to make changes in the cheder, why don’t you come and help us? Let’s face it, the school is much too big for one menahel. Why don’t you come and work at the Kamenitz cheder?”

It wasn’t an easy decision, Reb Binyomin says. At the time he was spending his days happily learning in yeshivas Mir. Before accepting Rav Scheiner’s offer, he went to seek Rav Aharon Leib Steinman’s advice. The question was complicated, especially since at around the same time, Reb Binyomin had also received another offer, one from a yeshivah gedolah.

“There aren’t many people who can do the job that Rav Yitzchok wants you to do at the cheder,” Rav Aharon Leib told him, “which means that if Rav Yitzchok is asking you to do it, it’s because he feels you can do a good job. Regarding the offer from the yeshivah gedolah, that’s the kind of job many people can do. When you ascend to the Olam HaEmes after 120, they will ask you what you did during your time in this world. In response, you will tell them that you did a job that many others could have done, and who knows whether some of them could have done it better than you? On the other hand, the position at the cheder is more of a unique role, and if Rav Yitzchok feels that you’re the one to do it, then do it.”

Avrohom Scheiner, Rav Yitzchok’s son and one of the cheder’s first students, says he remembers looking at his class picture from when he was a young boy. “My father was there looking at the picture together with me. It was a funny thing, but the picture was taken so long ago that I could barely recognize myself. But not my father. Not only did he recognize me, he recognized every single child and was able to name them even though decades had passed since the picture had been taken.”

The reason was simple: Because Rav Scheiner cared about every single child. And when you care about something, when it’s that important to you, then of course you remember.

After Rav Scheiner was niftar, Rav Binyomin Kohn was talking to a friend who wanted to hear a story about the famous rosh yeshivah.

Reb Binyomin thought for a minute, and then remembered a story that summed up Rav Yitzchok Scheiner perfectly:

“There was a Kamenitz family wedding one evening, and when I arrived and approached the Rosh Yeshivah to say mazal tov, I saw that he was speaking with one of the yeshivah’s mashgichim, and I overheard part of the conversation. It was a pretty serious exchange. ‘I want to tell you a parable that we could compare this to,’ he was saying to the mashgiach. ‘Say it happened that a bochur ate treif on Yom Kippur, chas v’shalom. Then along comes the mashgiach, and he rebukes the bochur because he didn’t wash negel vasser before eating it. It’s the same thing here,’ the Rosh Yeshivah went on. ‘You’re focusing on a minor point. But I have a question for you: Do you know where this bochur is all day? Do you know what he’s doing, what he’s involved with?’

“That was the gist of the conversation I overheard. Seeing that Rav Yitzchok was involved in an important discussion, I figured I would give them some space and return in a few minutes. I came back ten minutes later and found the Rosh Yeshivah still going strong: ‘I understand that you want to throw this bochur out of the yeshivah. I understand that this is what you are prepared to do for him. But let me ask you a question. Have you done anything else for him besides trying to throw him out? Have you spoken with his maggid shiur to see what his level is in learning? Have you tried to find out what he’s doing all day and why he’s so unmotivated? Have you tried to find him a chavrusa, one who would be able to motivate him, or, alternatively, maybe tried learning with him yourself, which as you know would be a big kavod for him? Maybe if you do some of these things, you wouldn’t have to throw him out. Let’s look at his history. Let’s see what we’ve done for him before we make such a drastic move. After all, this is his life that we’re talking about!’

“This was the Rosh Yeshivah’s approach to chinuch: no decisions before knowing all the facts. He would never throw out a bochur without thoroughly investigating the bochur’s entire history. To his mind, anyone who calls himself a mechanech has to be ready to turn over the world before giving up on a student.”

Author RABBI NAChMAN SELTZER has captured the essence of Rav Yitzchok Scheiner – gadol on one hand, master mechanech on the other – in a soon-to-be released book by ArtScroll. Some excerpts that shed light on the lesser-known side of this great man:

PROFIT MARGIN

You can see a person’s greatness and the way he feels about himself from the employees he hires and the people with whom he chooses to surround himself. There are some bosses who will hire mediocre staff, perhaps apprehensive that they will be overshadowed by people who are just as great (or greater) then they are.

At Kamenitz, it was the other way around. Here was an institution where the principals were leaders in their own right, because Rav Yitzchok insisted on hiring the best people to head his cheder, yeshivah ketanah, and yeshivah gedolah. Such was his dedication to his talmidim, giving them only the best.

Rav Binyomin Cheshin began his career in Kamenitz as a rebbi in the highest grade of the cheder. From his class, the boys went on to yeshivah ketanah. After about six years, Rav Yitzchok made him a menahel. Rav Lipa Zilberman was serving as principal at Kamenitz at the time, and Rav Yitzchok hired Reb Binyomin to work with him. Not sure whether he should accept the job, Reb Binyomin went to ask Rav Moshe Aryeh Freund, head of the Eidah Hachareidis beis din.

He advised Rav Cheshin to accept the offer, explaining his reasoning by way of a parable.

Let’s say someone has a store, he said. He sells a certain amount of merchandise for a good price, making a nice profit on every item he sells. But say the same person owns a factory. Now he is selling many more pieces. Even if he makes less profit on each piece, the end result is that he is making much more money, because the volume of sales is much higher.

Rav Freund was telling his visitor that being the menahel of a cheder meant that he would be responsible for the chinuch of many more children and that his profit would be infinitely higher as a result.

Rav Cheshin took his counsel and accepted the offer.

NOTHING PERSONAL

“Soon after I started working at my new job,” Rav Binyomin Cheshin relates, “Rav Yitzchok asked me to come and see him.

“‘You’re going to do the same thing that I do,’ Rav Yitzchok said to me. ‘The children in our cheder are Hashem’s children, and ich, dir — me, you — are all doing the same thing: helping to increase the kavod of Hashem. I work with older bochurim and you with younger and since you are working with young children, your role is probably more important than mine because you are working with holy neshamos that have never tasted aveiros. So I want to tell you one thing: Whenever you are doing something in the cheder, you should think to yourself, Whatever is best for the children. That should be the foremost reason for whatever you do, without personal considerations. Do whatever is best for them.’

“He concluded his remarks by uttering the expression ‘V’idach zil gemor’— meaning, use this statement as a prism through which to view every scenario that arises. This is the mission statement that must be kept on the forefront of your mind at all times. No personal considerations. Only what’s best for the children.’”

When asked what Rav Scheiner meant by personal considerations, Reb Binyomin answers, “Let’s say I’d like to teach a certain masechta to the children because that’s what I’m currently learning, but it would be better for them to learn Eilu Metzios. That would be an example of doing what’s best for them. But there are a million examples of choices that come up all the time. Rav Yitzchok was telling me that any question I had should be settled by asking myself, ‘What’s best for them?’ ”

NO HARM DONE

Rav Yitzchok was actually a very demanding employer, who knew what he wanted for his company and expected perfection. After all, these were Hashem’s kinderlach, and they deserved the best. For this reason, he was very involved in deciding which rebbeim were going to teach at the cheder.

Different people look for different qualities in the rebbeim they hire. With Rav Yitzchok, step one for a rebbi was that he needed to be a talmid chacham. Step two was the matter of classroom control. In this he differed from many others in school administration, who argued that the most important thing is whether a teacher has the personality necessary to impose discipline and ensure that everyone behaves. Most principals will tell you that if there is no discipline, nothing will be achieved and everyone will be wasting their time.

Rav Yitzchok looked at the matter from a different perspective. In his opinion, the most important thing was that the rebbi should be a talmid chacham. After that, the rebbi needed to have enough of a natural understanding when it came to matters of discipline so that he would be able to learn from those with more experience. If he possessed a certain amount of natural discipline skills, he could be taught the rest. But if he didn’t know how to learn, he would end up teaching the wrong information and that was unacceptable.

“One rebbi had been hired by the principal who worked in the cheder before me,” Rav Binyomin Kohn relates. “Rav Yitzchok wasn’t happy with him, because he felt that the rebbi’s own learning wasn’t up to the level that he wanted for his staff. Time passed and Rav Yitzchok saw that he was still teaching at the cheder.

“‘Why is he still here?’ he asked me.

“‘I’m able to sleep at night knowing that this rebbi is in the classroom,’ I told Rav Yitzchok.

“‘What do you mean?’

“‘I mean that he’s nice to the children. He doesn’t abuse his position, and he takes care of the charges in his care. He may not be the biggest talmid chacham, but I feel that he is essentially harmless.

“Rav Yitzchok’s reaction was powerful. ‘How can you call that harmless?’ he asked me. ‘There are 30 children in the class, and they’re going to be with this rebbi for an entire year. Wasting a year of their lives is called harmless?’

“In the end, I found a way to ease the rebbi into a different job in a way that didn’t hurt his ego. And I knew that Rav Yitzchok’s incredulous uttering of the word ‘harmless’ would remain with me for all time.”

NOTHING ELSE MATTERS

Rav Yitzchok often spoke to children at various schools on special occasions such as a siyum. Rav Yitzchok was a master orator, whatever language he was speaking. At one particular gathering, Rav Yitzchok looked around the room and said, “I want to tell you all a story about the Holocaust.”

He spent a few minutes explaining what happened during that dark epoch of Jewish history, and then told them about one Hungarian survivor who married after the war and was blessed with a daughter whom he named Leah. When she became of age, Leah became a kallah. Now, this kallah, Leah, had a friend named Tzippy. When Tzippy came home all excited because her friend had gotten engaged, Tzippy’s father asked his daughter the name of the friend who had become a kallah. When Tzippy’s father heard Leah’s last name, he surprised her by saying, “I would like to attend her wedding.”

This was very strange, since in general fathers don’t usually go out of their way to attend the weddings of their daughter’s friends. Yet here was Tzippy’s father asking her to tell him the date of the wedding and the name of the hall.

When Tzippy’s father arrived at the wedding, he took a picture from his inside pocket. Handing it to his daughter, he said, “‘Please give this picture to the kallah and ask her to show it to her father.”

Tzippy did as her father requested, and in due course the kallah’s father found himself staring at the picture. From the expression on his face, it was clear that something major was going on, and everyone waited for an explanation, which wasn’t forthcoming. Without saying a word, the kallah’s father returned the picture to its owner, who slipped it back into his pocket.

After the chuppah, when all the guests were sitting at the tables and enjoying the first course, Tzippy’s father rose from his seat and made it clear that he wanted to give a speech.

Everyone looked at him curiously. It was odd that this man, who wasn’t even from their circle, insisted on addressing them. This was the story he told them:

“I was a soldier in the American army during World War II. When the war was over, I was sent along with a group of soldiers to give out medicine and other necessities to the refugees in the various DP camps, where they waited to be granted permission to leave Europe and restart their lives. There in the DP camps, I met many survivors and tried my best to help them. It was hard to look at them, knowing what they had been through. They were so thin, beyond skinny, and I gave them chocolate, candy, and vitamins, then asked them how they felt. Then I would figure out what medicine they needed to take and how often they should take it.

“I also did my best to give them chizuk. I’d ask them to share the stories of what they had been through. I wanted them to talk and to cry. Somehow, I understood that the sooner they were able to remove the heavy stone that sat on their hearts, the sooner they would be able to live normal and healthy lives again.

“So it went until I reached one particular individual. Until that point, I would ask what they needed, and the people would give me a list. But with this man, things were different.

“When I asked him what he needed, his answer left me shocked. ‘I need a maseches Bava Kamma.’

“‘I came here to give you medicine,’ I told him. ‘Medicine and food.’

“‘Yes, I understand that,” he replied, ‘but it’s been four years since the Nazis pulled me away from my Gemara —it was a Bava Kamma. For four years, I haven’t touched or seen a Gemara, so if you really want to help me, if you want to save me, then that’s what I need. A Bava Kamma. Nothing else.’

“I decided to do my best to get him a Gemara. After asking around, I learned that there was a warehouse close by that had been used by the Nazis to store items belonging to Jews. There were thousands of seforim there, and the moment I saw that gigantic room, I was reasonably sure that I would find a copy of Bava Kamma there. I searched and searched, and eventually I unearthed a copy of the masechta. I brought the Gemara to the Yid, and when I handed it to him, an indescribable look of joy crossed his face. He held it close, and he said, ‘You saved me!’

“I needed to come here and speak to you tonight because the man I met in the DP camp, the man who wasn’t interested in chocolate or candy or even medicine, but only wanted a Bava Kamma, is this man, the father of the kallah. I had taken a picture of him soon after that memorable meeting and kept that picture all this time. How could I not attend this wedding after such an experience?’”

Having concluded the story, Rav Yitzchok looked at all the children at the siyum and said, “Kinderlach, this story is an example of what true simchah is. True simchah is not about gashmiyus, trips, vacations, or fun. True simchah is about holding a Bava Kamma in your hands after not being able to learn for four years. Leah’s father was skin and bones after the war. He was emaciated and hungry. But all he wanted was a maseches Bava Kamma.”

NOTHING LIKE THE TRUTH

Although years ago many of the chadarim of Jerusalem had not instituted the concept of report cards, Rav Yitzchok insisted that his rebbeim fill them out and that they be written as accurately as possible.

“If you’re just fooling everyone and writing glowing reports about a child who isn’t at the level you say he is, then what have you accomplished? Parents have to know the truth about their children,” he would say.

Sometimes it happened that a bochur who had graduated from the cheder wasn’t doing well in the yeshivah ketanah. When that happened, Rav Yitzchok would request the boy’s report cards from prior years. Sometimes he would call in one of the boy’s former rebbeim and ask him, “Tell me, what kind of a talmid was so-and-so?”

If the rebbi replied, “Average or mediocre,” then Rav Yitzchok would pull out the bochur’s report cards and put them on the table.

“If he was just an average child,” he would say, “why did you make him sound as if he was the next Rav Akiva Eiger? Did you give his parents any indication that their son was struggling?”

It didn’t take long for the rebbeim to understand that in the eyes of Rav Yitzchok Scheiner, honesty was the best policy.

One day Rav Binyomin Kohn was conversing with a rebbi from another cheder. This rebbi was finding himself at odds with the school administration because they were also starting to crack down on the matter of report cards. This rebbi didn’t understand why he should have to write the brutal truth to the parents of weaker students in his class. Reb Binyomin tried explaining the reasoning behind the policy, but he didn’t like it.

“Do you think I could ask Rav Yitzchok Scheiner about this?” he said.

“I’m sure Rav Yitzchok would be more than happy to discuss the issue with you since it happens to be an area about which he has very strong opinions, but as a friend, I’m warning you that you’re not going to get the reaction you want.”

The rebbi disregarded Reb Binyomin’s warning and went to see the Rosh Yeshivah.

“What do you want to write on the report cards?” Rav Yitzchok asked him.

The rebbi told him.

“Now show me a list of the boys’ real marks.”

“I haven’t prepared that yet.”

“Prepare it and come back to me when you have the information.”

The rebbi prepared a sheet with the class grades that were a more accurate reflection and brought it to Rav Yitzchok, who carefully studied the list.

“Tell me,” Rav Yitzchok he said, “on what do you base these marks? You write about this boy that he excels and about this boy that he’s almost excelling. What are you basing this on?”

“On the tests.”

“Okay, please bring me the marked tests.”

It took the rebbi a week to get all the material together. Eventually he returned with a test that had been taken by his entire class and that he had graded. Rav Yitzchok looked it over.

“This isn’t really a test,” Rav Yitzchok remarked after he had examined it. “It’s very easy. If a child can’t do well on such an easy test, he’s in trouble, no? This is the kind of quiz that every child should be able to complete easily. A child who got a 60 or 70 on this test is really very weak. And yet I see that you’ve written about such children that they are almost metzuyanim, almost the top boys. How did you arrive at such a conclusion? Clearly, some of these children are not metzuyanim and not almost metzuyanim — and their parents need to know the truth so that they can get them the help they need to succeed.”

EVERY CHILD COUNTS

Not long after Rav Binyomin Cheshin began working as one of the principals at the Kamenitz cheder, Rav Yitzchok Scheiner informed the new menahel that he wanted him to prepare a list with the name of every child in his care, along with a detailed assessment of how he was doing. Reb Binyomin wasn’t the only principal that Rav Yitzchok had asked to do this — because this was something that he considered crucial for the well-being of his student body.

“What does the Rosh Yeshivah want to know?”

“I want to know about behavior. I want to know whether a boy is listening in class. Also, it would be a good idea to mark down how many days a boy missed in the last month and how many times he was late.”

He wanted to know test marks as well.

Seeing that Rav Scheiner was serious and knowing that he didn’t have a choice, Reb Binyomin promised to get him the information.

It wasn’t a simple request. They were talking about every boy in every class from kindergarten up to sixth grade. There were two classes per grade, 14 classes altogether. But Reb Binyomin had no choice. He began assembling all the information, starting with a few sample classes. When he received the lists, Rav Scheiner studied them carefully.

At that time there were 35 children in each class, and in all honesty, the principal hadn’t really devoted much time to figuring out what he was going to do for the few children who were especially weak. Yet here was Rav Yitzchok Scheiner, rosh yeshivah of Kamenitz, looking him in the eye and asking him what the plan was.

“Look, I want to tell you something,” Rav Scheiner said at last. “Imagine if I lent you a thousand shekels, and when it was time for you to return the money, you gave me back nine hundred and fifty shekels, fifty less than the sum I gave you. Maybe you’d be thinking, This is almost the entire amount that you gave me. I know it’s not everything, but it’s close enough… “

Reb Binyomin was taken aback. Rav Yitzchok Scheiner was the rosh yeshivah of Kamenitz, in charge of its yeshivah gedolah, yeshivah ketanah, and cheder. He carried the weight of a huge Torah institution with many students on his shoulders. He had to raise millions of dollars every year and give several shiurim on a daily and weekly basis, not to mention the time he spent dispensing advice to various mosdos, the time devoted to his own learning, as well as to his family.

“Rosh Yeshivah, can I ask a question?”

Rav Scheiner nodded.

“I know how busy the Rosh Yeshivah is. I know how many jobs he does, and how many tasks occupy his time. So how does the Rosh Yeshivah have time to review these lists in addition to everything else?”

“Reb Binyomin, you’re right that I don’t really have time to sit with you and discuss the name of every child in the cheder. But I’m doing this because I want to make sure that you will take the time to do this. I know that if I don’t ask this of you, there is no way that you will make the time. So I ask in order that you will make the time.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 897)

Oops! We could not locate your form.