Deaf to My Concerns

I couldn’t lose my hearing overnight — could I?

As Told to Rachael Lavon

Around seven years ago, I found myself standing on the sidewalk, shaken to my core. My intuition, that crucial compass that guides and advises, had been completely discounted. I felt off-kilter, like the world was tilted, and I no longer knew which way was up or down.

It all started on a regular Tuesday morning while I was getting my kids ready for school. My husband usually calls after Shacharis while I’m in the middle of the morning hustle to see if I need anything picked up on his way home. I saw his number flash on the screen and held the phone up to my ear, but instead of pressing the answer call button I accidentally pressed the loudspeaker button. My husband’s voice came blaring through the phone directly into my ear. I felt something like a small shockwave course through my ear, and I quickly turned the loudspeaker off.

After a short conversation, I put the phone down and realized my ear felt weird. Throughout the day, it reverberated with an uncomfortable ringing sound that wouldn’t go away. I tried to go about my day as usual, attending a shiur and running errands, but I felt distracted by the strange feeling in my ear. As the day progressed, I began to feel nauseous and dizzy. I relayed what had happened to a friend, hoping she’d have some advice.

“Ok, so you heard a loud sound,” she said. “It’ll probably just take some time for the ringing to go away. Try to rest up, I’m sure it will be better in the morning.”

The consensus from other friends and relatives was the same — it would probably get better on its own. I went to sleep uneasy, but hoped a good night’s sleep would help.

It didn’t. The next morning dawned, and my condition hadn’t improved. I kept doubting myself. It’s not like I’d gone to a loud concert or been at a construction site! Could a phone call really damage my ear? As the day went on, I realized I was having trouble hearing out of my left ear. Sounds were muffled and unclear. My self-doubt morphed into anxiety. Ringing was one thing, but hearing loss was quite another.

By Wednesday afternoon, I called the local ENT and asked for an appointment as soon as possible. I felt tremendously relieved when the secretary told me I could come in that afternoon.

I sat opposite the doctor and told him about the phone call and the weird symptoms I’d been experiencing. He was dismissive but humored me by checking my ears, nose, and throat. He put his hands on either side of my face and asked me to open and close my jaw. At the sound of a click (the same click I’d had for ten years), he snapped his fingers happily.

“There it is. You hear that clicking in your jaw? That tells me that you’re under a lot of stress. Do you have young children at home?”

I nodded.

“A baby?”

“Yes.” I responded. “A six-month-old.”

“You need to get more rest. Go home. Relax, and try to take it easy.”

I shook my head. “But the loud sound from the phone…”

He waved his hand. “Trust me, a loud phone call wouldn’t damage anything in the ear. That’s not the issue. It’s stress. Try to get your husband to help out more around the house.”

“But… but I really can’t hear well out of my left ear…” I tried one last time.

“Look, if the symptoms persist throughout the weekend, then go get a hearing test on Sunday,” he said, quickly filling out a referral for the hearing test in case I needed it.

As I trudged home, I felt dejected. I was sure there was something going on with my hearing, but the doctor had made me feel like a child. It had been a humiliating experience. And his insistence that my sudden hearing loss was “nothing” hadn’t eased the dread curdling in the pit of my stomach.

It was a lonely night as I tried again and again to see if the loss of hearing in my left ear was real or a figment of my imagination. By the next morning I’d decided I wouldn’t wait until after Shabbos to get a hearing test. I scheduled an appointment for that morning, hoping the hearing test would come out perfect, and I’d discover I was worrying for no reason.

The results were shocking.

“The nerve in your left ear is dead,” the woman performing the test told me frankly. “You need to go to the hospital immediately.”

I tried to process what she was saying. It wasn’t like there was a blockage. There was no buildup of fluid or wax. The cochlear nerve itself was unresponsive. I walked out of the building, my mind racing so fast I felt numb. Get to the hospital? How? My nerve is… dead?

Finally, I had the presence of mind to take out my phone and call my husband. He jumped into a cab, picked me up, and we sped off to Hadassah Ein Kerem. My head was spinning the whole way. There were so many details. I had a nursing baby at home, a house full of kids. But all that mattered at that moment was getting admitted to the hospital.

At the hospital, my case had the doctors stumped. They knew I was suffering from sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL), but they weren’t sure why. Often, the sort of hearing loss I experienced comes about as a result of a virus, but I’d been feeling perfectly fine and hadn’t been suffering from any ailments before the phone call.

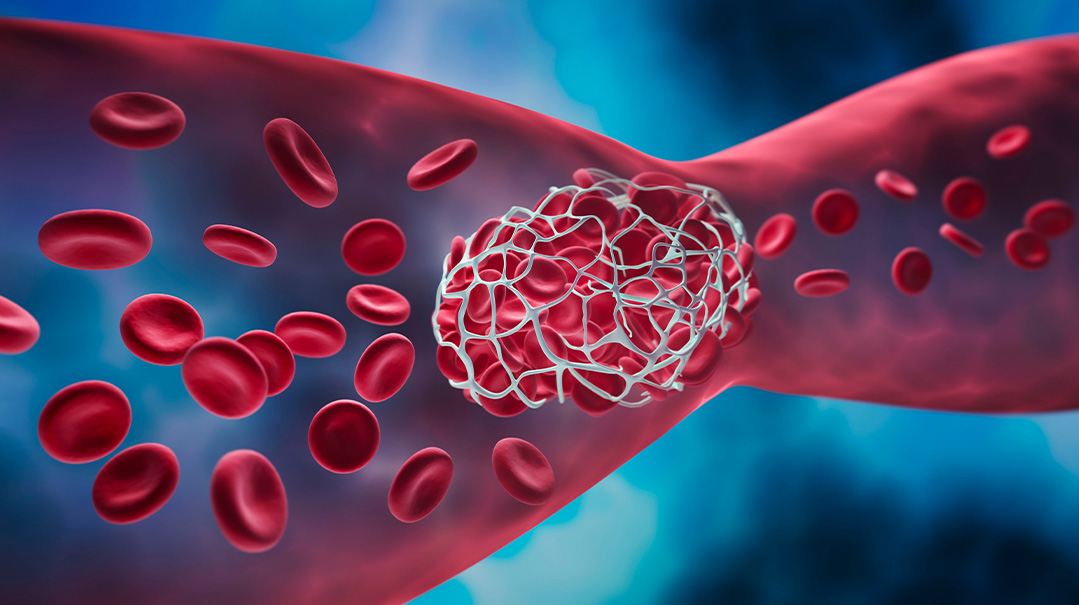

Each doctor who heard my story felt strongly that sensorineural hearing loss doesn’t happen in response to sound. The trigger for my particular case remains a mystery until today, but whatever the reason, the treatment protocol was clear — steroids and oxygen therapy around the clock to jump-start the nerve back to life. The key to recovery was the short time span, explained the doctors. The faster they could start treatment, the better chance my hearing could be saved.

Baruch Hashem, I’d gone early for the hearing test and hadn’t listened to the ENT who’d advised to wait until after the weekend. Soon after the onset of SSHL, the nerve dies completely and there’s nothing left to jump-start.

While we navigated the hospital maze, which took hours, our family doctor and my brother-in-law — a doctor in the States — were both on the phone with us, guiding and advising and reassuring us at every step. Amazingly, a good friend of mine is an audiologist and did her thesis on sensorineural hearing loss, the very condition I was suffering from. She kept on top of the situation, guiding me throughout and doing her best to make sure I was getting the best treatment possible.

The beginning of my hospital stay was very difficult because I didn’t know exactly what the outcome would be. We had no idea if my body would respond to the treatment or if the hearing loss would be permanent. There were a few other people in the ward with the same condition as me; a teenager, a young man, and an older man. There was no rhyme or reason for their condition; apparently it isn’t terribly rare, it’s just awareness that’s lacking.

Shabbos was a very vulnerable time for me, alone without the comforts of home or my family and still unclear about my prognosis. I was shocked to discover the world of chesed that exists in the hospital. There’s a family who makes Shabbos for anyone in need, week after week. Such a huge cross section of humanity showed up; the young and old, sick and healthy. We were served a tremendous amount of amazing food. I was stunned, thinking, Wow this happens every week, and I never knew about it.

After I started treatment, I began to feel some improvement. My whole system began to relax. I’d been so sure there was something wrong with me, and once I started getting the treatment I needed, I felt the pain of being invalidated dissipate.

On Sunday, I went for another hearing test in the hospital, and baruch Hashem, they were able to see that my nerve was responding. To my surprise, I was able to go home soon after that and was able to return to regular life quickly.

In the years since, I’ve never had any sort of relapse, baruch Hashem, or any residual symptoms whatsoever.

There are definitely times when I look back in awe at my miraculous recovery. I saw an internist a few years after this story occurred, and the doctor was flipping through my medical records when she stopped suddenly.

“You had sudden sensorineural hearing loss?” she asked.

“Yes, I did.”

“And your hearing was restored?” she went on with a look of surprise on her face.

I nodded. “Baruch Hashem, fully restored.”

“Wow.” She shook her head in amazement. “That’s incredible. My son had it, and he can’t hear at all out of one of his ears. It’s not so simple. Don’t take your recovery for granted.”

I certainly try not to.

I’ve never forgotten the experience I had with the ENT who wrote off my hearing loss as the manifestation of stress and anxiety in a young, busy mother. In fact, I penned a letter to the medical center where he works, but was never brave enough to send it. But I’m sharing my story now to show how disempowering self-doubt can be and how crucial it is to follow your instincts, even in the face of an “all-knowing” doctor. Listen to yourself.

SSHL at a Glance

Sudden sensorineural (“inner ear”) hearing loss (SSHL), commonly known as sudden deafness, is an unexplained, sudden loss of hearing either all at once or over a few days. Sudden deafness often affects only one ear.

Many people discover their hearing loss upon waking or after hearing a sudden pop right before their hearing begins to worsen. People with sudden deafness may also notice a feeling of ear fullness, dizziness, and/or a ringing in their ears.

Sudden deafness symptoms should be treated as a medical emergency and a visit to the doctor should be scheduled immediately. Receiving timely treatment greatly increases the chance that one will recover full or partial hearing.

Experts estimate that SSHL strikes 1–6 people per 5,000 every year, but the actual number of new SSHL cases each year could be much higher because SSHL often goes undiagnosed. SSHL can happen to people at any age, but most often affects adults in their late 40s and early 50s.

What causes sudden deafness?

Infection

Head trauma

Autoimmune diseases

Exposure to certain drugs that treat cancer or severe

infections

Blood circulation problems

Neurological disorders, such as multiple sclerosis

Disorders of the inner ear, such as Ménière’s disease

What’s the treatment?

Steroids should be used as treatment as soon as possible for the best effect and may even be recommended before all test results come back. Treatment that’s delayed for more than two to four weeks is likely to result in permanent hearing loss.

Source: The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 748)

Oops! We could not locate your form.