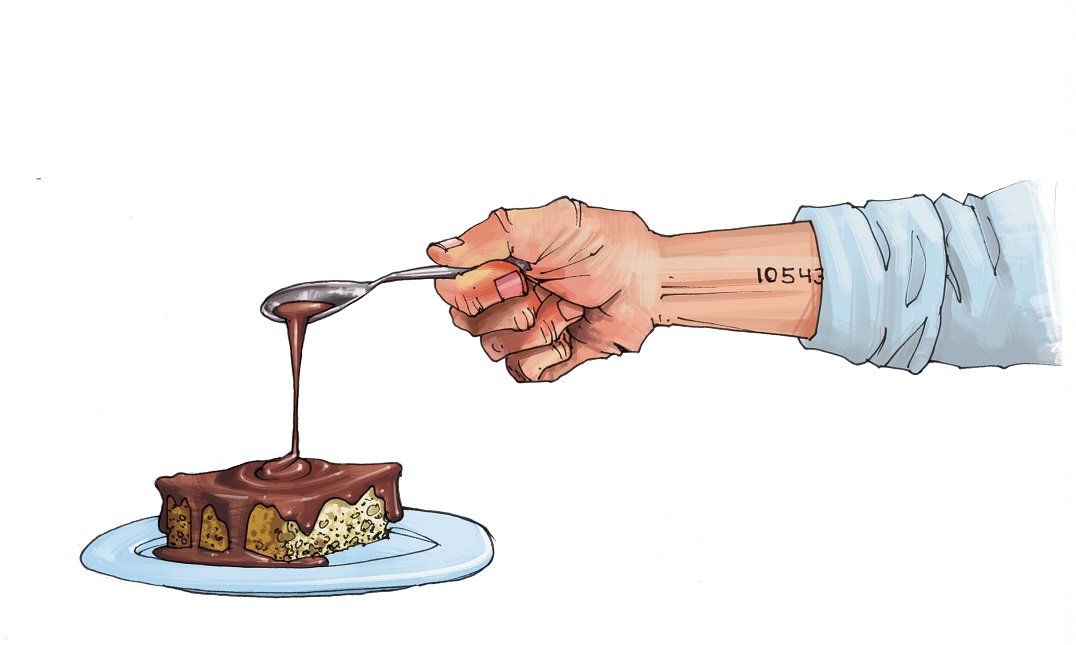

Blueberries and Cream

How did she get such remarkable blueberries, each one perfect?

The best part of my childhood was the summer. And the best part of the summer was exploring the woods near the bungalow colony we attended in Woodbourne, New York, often with my friend, Chaim Mordechai from Pittsburg, roaming far enough to feel free, but close enough to stay safe. Unlike cloistered Brooklyn, Woodbourne — more specifically, Maybrook Cottages on Budd Road just behind the fire station — was where I could find myself.

My father managed the bungalow colony. He was in charge of making sure the leaky pool was filled and rotting porch steps were replaced, and that made me the son of royalty. It was a small colony, maybe 25 bungalows. We were in bungalow #5, the one with the upside-down horseshoe over the door. My mother told me someone had put it up as a sign of good luck; I pondered the connection and never quite understood it. I remember the large Frigidaire with the heavy handle in our kitchen, which clonked shut as if you were closing a vault, and the bunkbeds printed with the words “US Army,” which also didn’t make sense.

Behind the pool was an overgrown campfire site. Behind that was a hill and up the hill, behind a short stone wall, was a cluster of blueberry bushes. Chaim Mordechai and I would often go there to pick the berries. The fruit was mediocre; there were a few dark blues, a lot of violets, some greens. But it was there for the taking. It was free, and picking them released my spirit.

Oops! We could not locate your form.