Blood Brothers

| September 5, 2023The Renewal movement celebrates 1,000 Jews who’ve gone under the knife to save a life

Photos: Langsam Photography, Naftoli Goldgrab

Early Morning Action

ATfour thirty-two a.m. on a crisp Monday morning, the parking lot at the 7-Eleven convenience store located just off Route 9 in Old Bridge, New Jersey, is just starting to show signs of a new day’s activity after a long night. An elderly man walks out of the store, breakfast in hand, and nods gently to the fellow entering. Drivers park abruptly, make their hurried purchases, and then get back on the road. There are no exuberant greetings here, no loud phone calls; the customers seem to obey the unwritten rule of thou shall not disturb the peace so long as it lasts.

One midsize SUV in the parking lot, though, stands in proud defiance. Its speakers are humming with incessant ringing, audible even to those outside. The rule-breaking SUV’s driver, Rabbi Moshe Gewirtz, serves as the director of Renewal, the trailblazing organization that facilitates kidney transplants within the frum community, and the 7-Eleven is an almost daily early morning stop for him. It’s a 20-minute drive from his Marlboro, New Jersey, home and on the way to all the area’s major hospitals. Most importantly, the store is conveniently situated just 30 minutes from the frum enclave of Lakewood — making it the perfect spot for him to meet kidney donors who need a ride to the hospital, chauffeured to the 7-Eleven by a volunteer for Renewal, where Moshe awaits and takes them the rest of the way.

Today’s surgery, taking place in the Hackensack University Medical Center, a world-class hospital located a stone’s throw from Manhattan, is a milestone for the Renewal team — it’s the organization’s 1,000th lifesaving procedure. I join Moshe in his car so I can shadow him for the day and get a front-seat view how one Yid literally gives the gift of life to another.

At four thirty-five a.m., we’re back on the road, Waze set to Hackensack’s transplant unit, and two steaming cups of exceptionally strong brewed coffee ensconced in each of the cup holders. But aside from the java, there are no hints of the wee hour. Moshe’s phone is constantly dinging with notifications and calls coming in from members of Renewal’s team. A text message comes in from a coordinator to confirm tomorrow’s surgery appointments; he takes a call from Rabbi Menachem Friedman, the director of Renewal national, who is arranging rides for patients and family members to the various hospitals; Mendy Reiner, chairman of Renewal, is checking in on the status of today’s transplant; and Rabbi Josh Strum, Renewal’s director of outreach, wants to touch base about getting their army of volunteers proper instructions on where to deliver Renewal’s famous care packages.

In between the calls, Moshe finds a few minutes to share some of his background with me. The journey to his position as Renewal’s director started off with his own kidney donation. He had been working as a kiruv rabbi for the Monmouth Torah Links organization when he was first exposed to Renewal’s lifesaving activities.

“I arrived at a routine doctor’s appointment in Lakewood with several minutes to spare before the appointment,” he remembers, “and I saw some people gathered around a sign that said ‘Renewal Event.’ I was vaguely familiar with the organization and decided to listen in on what they were talking about.

“Two doctors were presenting on the concept of kidney donation, and I remember hearing them say that when someone donates a kidney, their health is uncompromised while for the recipient — the one in need of a kidney, it’s literally a new lease on life. They described it as replacing a broken car part with a brand new one — and one that will im yirtzeh Hashem last him many years.”

Intrigued, Moshe filled out the paperwork, had his cheek swabbed by the Renewal volunteer, and left to see his doctor. Sometime later, he was notified that he was actually a match, and subsequently donated his kidney to a young Jewish mother who was suffering from renal failure.

“I remember sitting in the hospital bed,” he says, “and my coordinator handed me thank you letters from my recipient’s family. I was too worn out to read them, but one of them stuck out.” It was a letter written in big, childish scrawl containing a simple message:

Thank you for saving my Mommy’s life, now she can be alive at my bar mitzvah next year. Thank you,

Dovid, age 12

The next year Moshe attended 13-year-old Dovid’s bar mitzvah.

Over time, Moshe became an active member of Renewal’s “donor circle,” volunteering and speaking for the organization along with other past kidney donors, and when Renewal was looking to expand its team, the organization reached out to the young, dynamic rabbi. Together with Chana Greenfeld, he served for the past three years as a donor coordinator, helping ensure a smooth, pampering process for donors, and last year was tapped to serve as the organization’s director. Yet even as his responsibilities within the organization grew, Moshe never gave up his donor coordination position, something typical of Renewal staff members, who feel privileged to be on site in the hospital, stewarding donor and recipient through what can be a daunting monthslong process, culminating in the day of the transplant.

As if to prove the point, our conversation is interrupted by a call that visibly excites Moshe — it’s this morning’s kidney donor. “Reb Moshe!” the donor exclaims, “we’re here at the hospital. Where should we go?”

“Sit tight,” Moshe says. “I have to make sure you’re cleared to go in.” He quickly dials the recipient’s wife, explaining that he has to ensure that the donor and recipient do not see each other before the surgery.

“It’s very intense to see the person who will be cut open to save you,” Moshe says, “and generally, recipients are nervous the day of the surgery and not in the best emotional state. We’ve found that it’s better to keep them apart so the donor is under no pressure and has the ability to back out until the last minute. Meeting a recipient and his family might put additional pressure on the donor.”

It can be quite a feat to coordinate the two couples’ entrances, but Moshe finesses it deftly. “It’s like a chassan and kallah coming into the wedding hall,” he quips. “They have to be in the same building, but cannot see each other before the chuppah.” He confirms that the recipient still hasn’t arrived at the hospital, and calls the donor back, giving him clearance to enter the lobby. “Wait for me,” Moshe tells him, “we’ll be there shortly.”

At precisely five twenty-nine a.m., we arrive in the lobby of the Helena Theurer Pavilion, Hackensack’s state-of-the-art, nine-story surgical and intensive care tower, 530,000-square-feet of medical space incorporating the latest technology into what Hackensack calls its “smart hospital.” The gleaming lobby has frosted glass privacy barriers surrounding some of the seating area, allowing us to see the silhouette of a tallis-clad figure swaying back and forth, the first rays of morning sun pouring and bouncing off the glistening atarah. It’s Reb Ezreal Spitzer, today’s hero, who, like the preceding 999 Renewal heroes, will be undergoing surgery to donate his kidney to save a life.

We also meet other members of the Renewal team. They’re clearly at home in the hospital walls, greeting security guards, nurses, and patients with a liveliness that is hard to match prebreakfast. Bleary eyed patients and their families are trying to make sense of this motley group of chipper rabbis — all pictures of good health and seemingly absolutely thrilled to be spending their morning in the sterile hospital setting.

The group tarries in the lobby, talking to Ezreal and his wife, joined by Marian Charlton, transplant coordinator. The white-coated Hackensack transplant coordinator, who is on a first name basis with the Renewal team, tells me they are “remarkable.” Once Ezreal is whisked up to the pre-operating room, we run back to the hospital’s entrance to greet the second celebrity of the day — Rabbi Shlomo Uzhansky of Jackson, New Jersey, who will be receiving Ezreal’s kidney. Moshe greets Rabbi Uzhansky and his wife with a hearty “mazel tov!” and together we head upstairs to help get everyone settled.

Renewal director Rabbi Moshe Gewirtz (L), who began his journey as a kidney donor himself, with founder Mendy Reiner, president Rabbi Sendy Ornstein, and executive vice president Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz. Giving a piece of yourself to save another life

A Joyous Korban

Once the donor and recipient are each settled in their respective pre-op rooms, we head first to talk with Mr. Ezreal Spitzer of Monroe, New York, the man who will soon hold the distinction of being Renewal’s 1,000th donor.

The 36-year-old Satmar chassid wears many hats. For one, he’s the owner of QRock Builders, a construction firm that specializes in customizable steel, designing buildings for end users ranging from agricultural warehouses to industrial workshops. The QRock project portfolio includes commercial and residential buildings, and QRock recently won a highly coveted contract with Federal Steel, one of the largest steel manufacturers in the United States, whose team was looking to break into the New York market.

Aside from his professional construction hat, Ezreal is also a volunteer member of the KJFD (Kiryas Joel Fire Department), donning a fireman’s gear when calls come in. And in just a few hours, he’ll have another outstanding achievement to his credit.

“Today,” Ezreal tells me from his hospital bed, “I’m becoming a kidney donor as well.” It’s obvious that the donation is a source of pride for Ezreal and his wife, and Moshe tells me that the immense joy in literally being able to give a part of one’s self to enable another Jew to live is characteristic of kidney donors, something they rightfully take immense satisfaction in.

“I feel like I’m bringing a korban far der heilegeh Bashefer,” Ezreal says, his voice quivering with emotion. “Not everybody has the zechus to do what I’m about to do, and it may not be the right thing for everybody, but what can I say? Hashem has a massive Klal Yisrael, a massive military, and I can be a part of that, giving myself far der Bashefer’s kind. Un ich zog dem der emes,” he says, slipping into his native Yiddish, “der gantzeh zach is nor Renewal, it’s only because of Renewal.”

Five years ago, a mashpia of Ezreal confided to his talmidim that he was suffering from kidney failure, his kidneys operating at minimal levels. “I don’t want you to answer me right now,” Ezreal remembers his mashpia saying, “but there is a way you can be of assistance.” He wasn’t asking for money, emotional support, or protektziya to get into a major doctor. He needed a kidney.

The alternative was death, and the looming prospect of a young father, husband, and mashpia passing away hung over his words like an impending storm. He gave his class the number for Renewal and bade them well.

That evening, Ezreal dialed the number and the organization immediately sent over a testing kit, consisting of a simple cheek swab that he sent back to Renewal’s Boro Park headquarters.

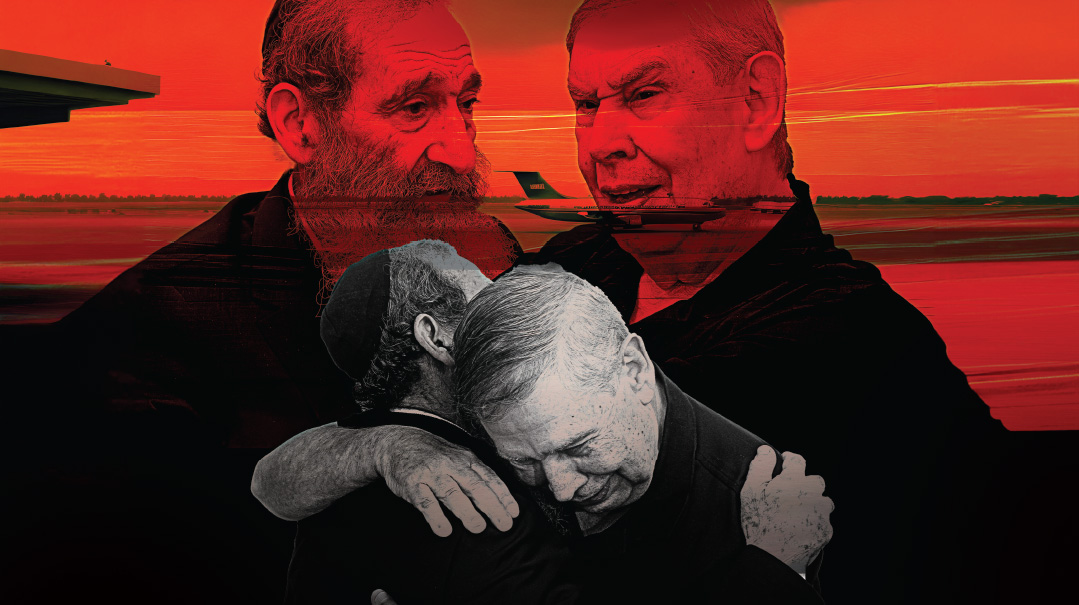

This morning, donor Reb Ezreal Spitzer (above) will be Renewal’s thousandth donor, passing his lifesaving kidney on to Rabbi Shlomo Uzhansky. “I feel like I’m bringing a korban”

All in Good Time

Ezreal wasn’t a match for his mashpia (for whom a different match was found, and chasdei Hashem, “he is better than ever,” Ezreal says), but his swab was kept in the Renewal database. A year and a half later, Ezreal received a call from an unfamiliar number. It was Miriam Lefkowitz, Renewal’s recipient coordinator on the other end. Without fanfare, excitement, or pressure, she gently informed him that there was a recipient who needed a kidney, and that he was a match. If he was interested, she told him, he could call back and they would advise him on how to proceed.

“It was a pleasant call, very friendly and without the slightest pressure,” Ezreal recalls. Moshe confirms that their no-pressure tactic is by design: “We don’t want people feeling they were coerced. We present them with the opportunity, and we’re here to support them throughout, but we want the choice to come from deep inside of them.”

At the time Ezreal decided not to go ahead with it, and it was not until he got a third call a full year later notifying him that he was a match for another person in need that Ezreal was all in.

What clicked the third time? “I don’t know myself exactly why,” he admits. “I guess because it was really his kidney.” And he means it; when he informed his children about his decision, he told them there is a Yid out there (whom he knew nothing about…) who was born with three kidneys, and that one of them was in Ezreal’s body. “I’m going to surgery to give back my pikadon,” he told them.

Ezreal describes how Moshe accompanied him to the hospital for the battery of tests he had to undergo to ensure that he could donate, and the chizuk Moshe imparted. “Even if the hospital doesn’t clear you to donate, or even if you decide not to move forward, just the fact that you came to the hospital for a full day to undergo invasive tests for another Yid, that is a zechus. If you decide to move forward, I’m here to help, but you — and only you — are the one who can decide to do that,” Moshe told him.

When the results came back and Ezreal was cleared to donate, he decided that, yes, he was ready to move forward, to donate his own kidney fahr a tzveiteh Yid.

Perfect Matches

In a sense, it was providential that Ezreal only came around the third time. A recent medical discovery in the last year and a half has allowed Renewal to develop a system that pairs kidney donors and recipients to an extent that is, quite literally, unmatched in the entire world.

Menachem B. Friedman, director of Renewal National, explains: “I’ll tell you a story,” he says. “Last year, we had a kidney donor who committed to donate, and after he’d already agreed, we told him he was actually a perfect match for the recipient we set him up with.

“He was very excited knowing that he was a ‘perfect match’ and mentioned it to the surgery team in the hospital. The nurses acknowledged that he was a match in the sense that he shared the same blood type as his recipient, and that the recipient’s body hadn’t developed antibodies towards his blood type, but they downplayed the fact that his match was better than average.”

The disappointed donor felt he’d been misled by Renewal’s team and called Menachem to express his indignation. Menachem was happy to clarify, and explained that while he was indeed a “perfect match,” there was a reason the hospital staff hadn’t shared his enthusiasm. He then proceeded to give the donor a brief medical class over the phone. It’s a bit technical, but Menachem insists that we hear the medical breakthrough that Renewal has capitalized on, ensuring not just kidneys for Klal Yisrael’s recipients, but also the best possible outcomes for these transplants.

“Hospitals look at the blood type and antibodies — which is an ‘army’ of sorts operating in the blood that keeps us alive and well by attacking any parasite that may enter our bodies,” he explains. “Thus, even if two people share the same blood type, if one of them developed antibodies to the other’s DNA makeup, those two people would be incompatible because the recipient’s antibodies would fight the external threat to it — in this case the tissue of the kidney — and would reject the organ. So when people say that someone is a ‘match,’ on a basic level it means that the two individuals have the same blood type and no antibodies toward each other.”

In more technical terms, Menachem explains, when donor and recipient human leukocyte antigens (or “HLA”) are matched, donor tissues are significantly more likely to be accepted by the recipient’s immune system. Until two years ago, this was the universally accepted method of ensuring transplant compatibility.

There is a slight hitch, though, Menachem continues. “The body’s immune system is wired to fight foreign substances, so even though previous antibodies don’t necessarily exist, when the new kidney is placed in the donor, the body will automatically develop new antibodies to fight it.”

To prevent this, kidney recipients are prescribed immunosuppressants, an anti-rejection drug that inhibits or prevents the activity of the immune system, thus lowering the chances that the body will fight the new kidney. But these immunosuppressants have a risky side effect. Since by their very nature, immunosuppressants are designed to weaken the immune system, in the event that a kidney recipient ever develops a condition that would necessitate boosting his or her immune system, medical convention would be to stop taking the immunosuppressants so the immune system can revitalize itself to fight the new disease.

“It’s a catch-22,” says Menachem. “The body needs the immune system to perform at optimal levels to fight the new disease, yet at the same time the system is now armed and can end up rejecting the kidney.”

A year and a half ago, Menachem, who flies around the country to establish relationships and facilitate transplants in hospitals out of the metro NYC area, found himself coordinating a transplant in the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. The affable rabbi enjoys talking medicine with doctors, and got into conversation with Dr. Mikel Prieto, the surgical director of the Kidney and Pancreas Transplant program and the Pediatric Kidney Transplant program at Mayo Clinic.

Dr. Prieto told Menachem about a fascinating study that surfaced from a university in Winnipeg, Canada, in which immunologists discovered that 90 percent of patients who, in Menachem’s words, “not only matched in blood type and HLA, but also matched their recipients in Class 2 antigens with 0 eplet mismatch,” did not reject the foreign kidney even when immunosuppressant use subsided.

Menachem gets visibly animated at that last sentence, reliving the medical breakthrough. The science is getting a bit hard to follow at this point, and despite my assertion that Mishpacha is not a medical journal, he insists on showing us the study, entitled, “Class II Eplet Mismatch Modulates Tacrolimus Trough Levels Required to Prevent Donor-Specific Antibody Development,” authored chiefly by Dr. Chris Wiebe, BSc, BSC Med, MD.

As academic and scientific as the paper is, for Renewal, the discovery was a game changer.

Sensing that the medical jargon may be just a tad beyond my scope, Menachem eases back into layman’s language. “If you’re buying a sneaker, and you tell the salesman you want a size eight, you’ll get that size, but not the exact sneaker you’re looking for. If you get more specific — say you want a size eight Nike Jordan blue sneaker with red shoelaces — you’ll get something closer to what you’re looking for.

“The old system matched on a basic level, and now we had the opportunity to match on a much more precise level. We used to look at serological levels, and now we have the ability to match on a molecular level.”

It’s not only that a perfect match is safer, but because the body will be more receptive to it, the kidney usually lasts longer and the quality of life for the recipient is increased manifold.

So when the unhappy donor called from the hospital, Menachem was glad to explain to him what was happening. “The reason they aren’t excited about the match,” Menachem told the donor, “is because they don’t look for a specific match! They’re happy with the basic match, and so they never developed the system to determine the more specific matches.”

There are two reasons, he says, why hospitals don’t incorporate the advanced matching system.

The first reason touches on the single factor that differentiates Klal Yisrael from the general population. “They have a very limited pool of donors,” he says. “Contrast that with our own community in which we can have hundreds of people coming out to get swabbed in one day. This allows us to be picky until we land the Cadillac match. In the general population, though, they are lucky if they get a donor at all; they’re not going to start looking for an even more precise one, no matter how much quality of life may be impacted.

“And finally,” he continues, “most hospitals can’t simply implement changes to existing systems on a whim — a proposed change has to make its way through the bureaucratic system with its multitiered hierarchical structure.”

Not so Renewal. When they heard about this discovery that would enable them to not only identify kidney matches, but also pinpoint the best matches available, they went all in. A customized software was developed, employing the most advanced technology to analyze the samples they received and LabCorp results of potential donors and recipients to find the perfect match.

Massimo Mangiola, PhD, a clinical associate professor at NYU Langone Health and one of the world’s top immunologists, was hired to oversee the cutting-edge software. Once a week, in a relatively modest Boro Park office, the Italian-born Mangiola sits side by side Renewal’s yeshivah-educated staff, utilizing the world’s most advanced kidney matching software and running searches that will identify the very best kidney donor for another Yid.

Mishpacha’s reporter shares excited, thankful moments with Rabbi Gewirtz and recipient Rabbi Uzhansky, the young father and kiruv rabbi about to get a new lease on life

Bad News, Good News

Ezreal’s swab was a “Cadillac match,” on every molecular level that Menachem rattled off, to Rabbi Shlomo Uzhansky, a 41-year-old kiruv rabbi residing in Jackson, New Jersey. Rabbi Uzhansky and his wife are in good spirits as they await the surgery, and Rabbi Uzhansky gives us a brief synopsis of his background.

Originally from Kiev, Ukraine, and raised in Philadelphia, Rabbi Uzhansky learned in yeshivahs both in Israel and the US before receiving his semichah from Lakewood’s Beth Medrash Govoha. He married Dr. Chana Uzhansky, a Philadelphia native born to former refuseniks Barry and Elena Iann, and the couple threw themselves into strengthening the Torah knowledge and religious commitment of folks whose backgrounds were similar to their own.

Together, at the behest of RJJ president Dr. Marvin Schick, who was concerned about the plight of Russian Jewry, the Uzhanskys founded the Staten Island Hebrew Academy, a kiruv-oriented school for children of Russian-speaking Jews. Rabbi Uzhansky — or “Rabbi U” — as he’s known, proudly bore the title of founder, while his wife and partner acted as the Supervisor of Education and president of the Board of Directors.

The couple would travel in every day from their New Jersey home to their school in Staten Island where they would transmit their Torah knowledge to children of a generation whose Yiddishkeit had been snuffed away and was only starting to rekindle. Empathetic, caring and in tune with various cultures, Rabbi Uzhansky decided to train as a professional social worker, which turned out to be a blessing when he found out he was suffering from kidney failure, as he was able to see clients remotely from the dialysis center.

The rabbi relives his first brush with symptoms of kidney disease. “I started becoming very tired. A 15-minute walk took me over an hour,” he recalls. When he realized the symptoms weren’t letting up, he went to his doctor, who took a blood sample. When the labs came in, the doctor sent him straight to the emergency room. At the hospital, they ran a battery of tests and when the results were in, the doctor walked into his room, a grim expression on his face.

“I have good news and bad news,” the doctor told him. “And the bad news is that you are in kidney failure.”

According to nearly every single statistic available, the diagnosis was the equivalent of being handed a near certain death sentence. The young father, devoted husband, and successful kiruv personality was devastated. Thoughts of his family sitting down at the Shabbos table without an abba sitting at its head flitted through his mind.

But then the doctor continued. “The good news is that your community has Renewal,” he told Rabbi Uzhansky. “You are going to call them, they’ll get you a kidney, and you’ll be good as new.”

And he would be, because Ezreal Spitzer wanted to be there far der Bashefer’s kind.

The couple followed the doctor’s orders, getting in touch with Renewal, who immediately stepped in. “They were positive, sweet, and kind,” Mrs. Uzhansky says, recalling her first phone call, “and they preserve the patient’s dignity in what can be a very difficult process, making sure everyone is keeping positive.”

They weren’t just maintaining a positive façade. Confident in the chesed of Klal Yisrael, the folks at Renewal were certain that a match would come up for Rabbi Uzhansky, even holding a kidney donor drive for him in Lakewood’s Beis Medrash Lutzk, where approximately 50 people were swabbed as potential donors. “They even advised us against me donating to my husband,” Mrs. Uzhansky continues, “because realistically speaking, both parents can’t go AWOL from the family.”

Like in the previous 999 rounds, Renewal was correct: Mr. Ezreal Spitzer’s data had been added to the Renewal database several years earlier after he did a cheek swab, and the software immediately picked up the match. Renewal then sent the results showing the match to the hospital (where, as a matter of policy, there is no reliance on outside tests), whose team ran independent tests to verify the information, and presented the hospital with all necessary paperwork to get the ball rolling. Once everything was confirmed, a Hackensack representative called Mrs. Uzhansky to tell her the wonderful news. It was Tishah B’Av, and Mrs. Uzhansky, who broke down upon hearing the stunning revelation, told the hospital rep that she had “ruined her day of mourning.”

A date was set for Renewal’s kidney transplant Number 1,000, wherein a magnificent mosaic, a chassidish contractor from Monroe would give his kidney to a Ukrainian kiruv rabbi from Jackson, with the transplant facilitated by a heimish organization based in Boro Park, attended by a litvish yungerman from Passaic, sponsored by a Sephardic member of the Deal, New Jersey community, and food for the donor and recipient delivered by two Modern Orthodox women from Teaneck.

It’s easy to sense the pulsating passion coursing through all the participants in this ultimate chesed. There are care packages filled to the brim with plush items delivered to both donor and recipient, bags of gourmet food for the next two days given to both wives, and constant check-in calls from a host of Renewal staff members.

“Hi, this is Aharon and Toba Feder, calling from Renewal. Is there anything we can get you? Do you have everything you need?” one such phone call went.

And what’s also evident is the genuine respect exhibited by the medical team here. The surgeons, the department heads, the nurses and orderlies, are all honored to be a part of Renewal’s story.

How did a group of frum businessman and rabbis — none of whom ever stepped foot into a formal medical class — found an organization that has transformed the lives of thousands of people, revolutionized an industry, pioneered the most cutting-edge tissue matching technology, and earned the utmost respect of the world’s top medical establishments while also turning the Jewish People into the world’s largest community of living organ donors?

After running back and forth between the two different hospital floors which hold the waiting areas for families of patients in surgery to see Mrs. Spitzer and Mrs. Uzhansky, delivering food and care packages, and finally hearing from the surgeons that both operations had successfully concluded, we got back in the car and headed to Renewal’s Boro Park headquarters to find out.

Once Upon a Dream

The car ride — our second of the day — was a window into the nuts and bolts of a Renewal. A call is placed to a chassidish mosad, reserving their premises to hold a swabbing drive the next Sunday. Moshe confirms a speaking engagement in which Rabbi Josh Strum will present at a cultural sensitivity training event for nurses, and touches base with another development coordinator, Rabbi David Schischa, who is flying to an out-of-town community to hold a kidney education event. Finally, he gets ready to call the donor and recipient for Tuesday’s procedure.

Moshe’s voice exudes excitement and buoyance as he checks with the donor if there is anything — food, a ride, anything! — he needs for the big day and reminds him that he will be there to accompany him throughout the procedure. When he calls the recipient of tomorrow’s transplant, the man on the other end of the line can hardly contain his enthusiasm. “I’m on my last session of dialysis!” he practically screams, before lowering his voice. “When I tell people here that after just one year, I’m getting a live donor kidney, they can’t believe it! They look at me like I’m crazy! Mi k’amcha Yisrael!”

It’s a phrase from a pasuk that aptly sums up the entire phenomena, and Moshe points out that the second part of the pasuk, “goy echad b’aretz” — can actually be proven by statistics. “According to data, transplants facilitated by Renewal account for 60 percent of all altruistic kidney transplants in New York, and 33 percent of all altruistic transplants in New Jersey. That’s 60 percent and 33 percent for a community that represents just 11 percent and six percent of each state respectively,” he says as we squeeze into a parking spot.

The Renewal office, located on New Utrecht Avenue, directly under the rumbling train, is clean, inviting — and functional. Belying the organization’s sterling reputation, its offices do not boast plush executive suites with soaring views. The employees walk with purpose, intent on going about their lifesaving work. We sit down around a kidney-shaped table in the conference room, and Mendy Reiner, Renewal’s founder and chairman, shares the genesis of the organization.

A talmid of the Erlau Rav, whose likeliness graces Mr. Reiner’s office (courtesy of a grateful kidney recipient), Mendy’s Renewal story started when he paid a visit to the Rebbe when the latter came to the United States in 2004. “I was in his house, and in wobbled a middle-aged man, looking like a drunk,” recalls Mr. Reiner. The unkempt man staggered over to the table, sat down opposite Mr. Reiner, and started telling him about his condition that prevented him from walking properly.

Mr. Reiner’s first instinct was to give him some tzedakah. “I took forty dollars out of my pocket,” recalls Mr. Reiner, but the man scoffed. “I don’t need your money,” he said, “I just want you to listen.”

He told Mr. Reiner that he was suffering from kidney failure — and that barring a miracle, his life was slowly coming to an end.

“I asked him what I could do to help, and he told me that he needs a kidney, which could be obtained on the black market for approximately $250,000. But I didn’t have that kind of money, and wasn’t sure how I could help him.”

When Mendy returned home, he told his wife about the encounter, who suggested that he should place an ad in the paper, asking if someone out there wanted to donate a kidney to a person in need.

That ad garnered about 25 phone calls. Several people called up, expressing a desire to donate and save a life, and yet others called to hear more about Mr. Reiner’s work, as they had relatives or friends suffering from kidney failure and they assumed that the individual who placed the ad knew a thing or two about kidneys.

They couldn’t have been more wrong. Mr. Reiner actually had almost no knowledge beyond the average heimish person about kidneys, their function, and the related diseases, treatments, and transplants. But while his kidney knowledge was admittedly limited, he did know about hearts. And he knew he was part of a community whose collective heart beat loud and strong.

The volume of calls inspired Mr. Reiner to dream of starting an organization whose sole objective would be to help match up people who needed kidneys with willing donors, and support their donors through the process. (Renewal predated Matnat Chaim in Israel: Founded in 2009 by Rabbi Avraham Yeshaya Heber ztz”l, the organization does similar work in Israel, encouraging and facilitating live kidney donation, and in fact passed the 1,000th transplant mark in 2021.) He took the idea to different organizations, offering to fund the first three years of operating costs, but his proposals were, to borrow a term from the medical world, DOA — dead on arrival. “They laughed in my face,” he recalls. But he refused to give up.

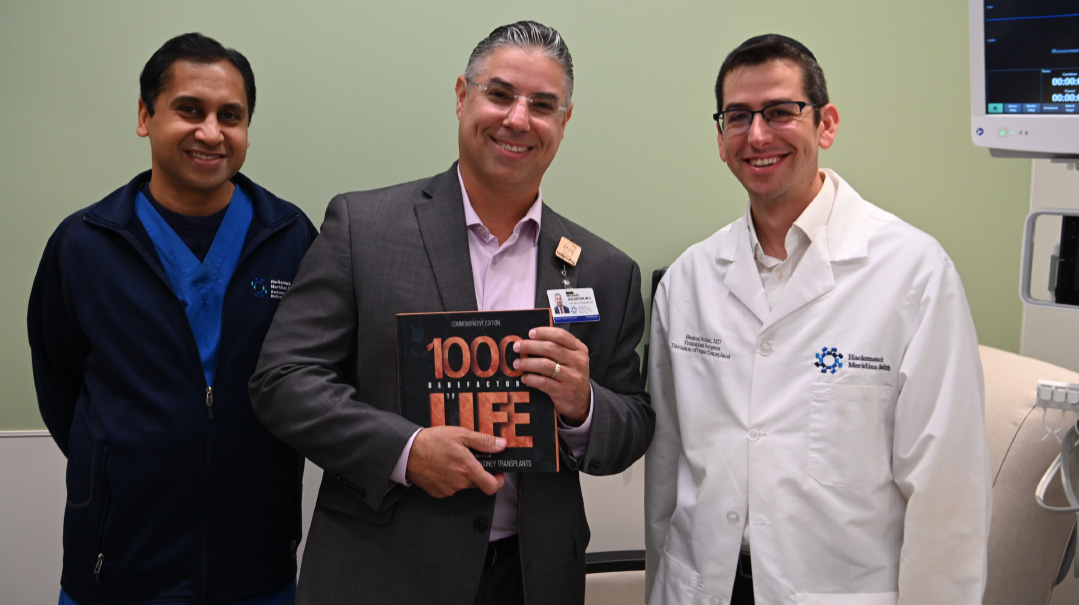

Dr. Michael Goldstein, director of Abdominal Organ Transplantation, Hackensack University Medical Center, with his medical team. More than any other group, Klal Yisrael has answered the call to altruistic kidney donations

A Slow Start

“I called my friend and rebbi in chesed, Shloime Meyer,” Mendy says, describing the Boro Park resident as a man “who was involved in chesed before chesed was the purview of organizations.” Shloime introduced Mendy to Rabbi Sendy Ornstein, one of the most prolific chesed entrepreneurs of our time. To date, Sendy Ornstein has founded Relief, the Refuah Resources, Premium Health Centers, and several other organizations, and Reiner was hoping Rabbi Ornstein would take on this cause as well.

Rabbi Ornstein remembers that initial call, as well his response. “What is this guy — crazy?” he remembers saying to his wife. “He thinks people are going to cut themselves open and give away a kidney just like that?” (His wife suggested, in jest, that they should make a “kidney pushke” and go around to various shuls, asking people to contribute theirs.) But Mr. Reiner told him that calls were still pouring in from potential donors in response to that one ad, and finally, after conducting some of his own research, Rabbi Ornstein was convinced.

They hired Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz to serve as director the nascent organization, which was cleverly named but impossibly tasked. There was no reference book on how to run a kidney transplant organization, no conferences to attend to hear tips from likeminded individuals, and literally nowhere to turn for guidance. The concept of altruistic kidney donations — defined by the US Department of Health and Services as “living donors who are not related to or known by the recipient” — was almost nonexistent. A study from 2014 shows just 184 altruistic kidney donations made in the entire United States that year. And while support for their endeavor was lacking, suspicion was plentiful.

“The whole concept of rabbis getting involved in the medically sophisticated world of transplant was met with sarcasm and suspicion from nearly every hospital representative we approached and every professional we spoke with,” recalls Rabbi Ornstein, “to the extent that the hospitals didn’t even want to let us in to meet with them.”

Rabbis Ornstien and Steinmetz (who now serves as Renewal’s executive vice president) were introduced to Dr. Stuart M. Greenstein, a transplant surgeon affiliated with the Montefiore Medical Center. Most frum dialysis patients went to Montefiore hospital and were under the care of Dr. Greenstein, and the doctor, though initially slightly skeptical about the project, agreed to come on board and help integrate Renewal into the medical system.

(In fact, when they first met, Reiner recalls getting what he terms a “mussar shmuess” from the doctor that the frum community is not doing enough in the organ donor area. “That’s why I’m here now,” Reiner said. “Let’s work together.”) The very first Renewal transplant was performed under Dr. Greenstein’s auspices in Montefiore, where Chaim Alter Berger, a life insurance agent from Boro Park, donated a kidney to a niece of Rav Chaim Kanievsky ztz”l, who came to America solely for this purpose.

Dr. Greenstein himself would go on to become one of Renewal’s most enthusiastic supporters in both the medical community and the frum world.

That first successful transplant led to another, then a third. Slowly, the barriers of distrust slowly started to erode, and some of the world’s most prestigious medical establishments — amongst them Columbia Presbyterian, Cornell, Mount Sinai, and NYU — agreed to work with Renewal. The miracle was beginning to unfurl.

Deep Pockets, Huge Hearts

AJ Gindi, Renewal’s community advocate and director of development (and kidney donor #144), the man universally credited for making Renewal a household name, had his roots in community service as the president of Magen Abraham Synagogue in Deal, New Jersey, and a board member of the Jersey Shore division of Bikur Cholim. He has leveraged both his passion for Renewal’s work and key philanthropic contacts in the world of Sephardic Jewry to enlist contacts who often step up to sponsor the transplants — at a cost of $18,900 each.

(The recipient’s insurance covers the medical cost for both donor and recipient, and Renewal picks up the tab for everything else associated with the transplant — from rides to and from the medical appointments to the donor’s lost wages during his time in the hospital and the recovery period afterward — which usually ranges from two to four weeks — and everything in between, including toys for the kids and extra cleaning help.)

“The Sephardic community is the most charitable in the world, and they just love what we do,” Gindi says, adding by way of explanation that “Here in Renewal, every single case we take on, every call we make, is life or death — and we pull through every single time.”

Mendy Reiner, the one who was crazy enough to believe in live kidney donation en masse for the frum community, has the last word at the Renewal offices: “Every day, I get to see the beauty of Klal Yisrael. A lot of times we focus on famous askanim and people who make noise. Don’t get me wrong — it’s important to be seen and get involved, but let’s remember that the hamon am of our nation is so precious.

The Yidden you see walking up and down the block, the people who sit in the middle of shul without fanfare and attention, are literally putting themselves under a knife to save for the life of another Yid. Not for money, not for kavod, but just because there is a person in need. Membership in Am Yisrael,” he says, “is priceless.”

“I’m not even sure why I agreed this time. I guess it was because it was time for me to give back my pikadon. It was Shlomo’s kidney all along”

From Their Hearts

A week and a half after the surgeries, we check in with Ezreal and Rabbi Uzhansky to hear how they are feeling. Ezreal sounds elated, relaying how the surgery is one of the highlights of his life and a milestone that his family cherishes.

Then Rabbi Uzhansky’s email comes in, short and succinct. “BH I’m doing well. A small setback (fever), but overall BH on all fronts,” it read.

Then a second message from Rabbi Uzhansky hits the inbox.

I’m composing this email amid a flood of emotions. At the outset of this difficult journey, I frequently pondered when the overwhelming challenges would come crashing down on me. Without a shadow of doubt, I can affirm that throughout it all, I’ve held no regrets, no bitterness, and no anxiety. Confronted with the news of complete kidney failure, I accepted it with composure, recognizing that preserving my mental well-being was just as vital as my physical health.

Looking back, I now understand that I was merely avoiding my emotions. Much like our bodies, our brains have a defense mechanism that activates in critical situations. It’s hardly surprising that I’m gradually beginning to experience this now, as my journey through end-stage renal disease takes an astonishing pause.

As a social worker, I frequently contemplate the reasoning behind certain behaviors exhibited by my clients. One such behavior is deliberate self-mutilation, like scratching or cutting. These individuals explain that it serves as a reminder of their vitality, piercing through the mental numbness that encases their thoughts. With the activation of my newly donated kidney, I can finally grant myself permission to undergo the full spectrum of emotions that were once unwelcome in my heart.

The absence of witnessing my children’s growth, the inability to provide for my family, the state of invalidity at the age of 42 — these are all overwhelming thoughts.

Leaving my wife as a widow and turning my children into orphans. Enduring agonizing treatments solely to delay the inevitable by a small margin. And now, the pure elation that this fate is no longer mine.

In this regard, my clients are on to something profound — pain amplifies the world, making it brighter, louder, and more vivid. Every connection is precious, each breath is a gift, and every hurdle is an opening. I express my gratitude to Hashem for allowing me the privilege of experiencing life with such intensity.

Renewal is an extraordinary organization that offers more than just kidneys. They are the architects of dreams, protectors of families, and champions of joy. They undertake their sacred mission with silent dignity, saving life after life. The incredible donors, often contributing organs to complete strangers, as in my case, stand as a testament to the strength of the Jewish community. As I frequently mention, the most remarkable aspect of the Jewish People is the Jewish People themselves.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 977)

Oops! We could not locate your form.